Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

21st Century Investing

Redirecting Financial Strategies to Drive Systems Change

William Burckart (Author) | Steven Lydenberg (Author) | Sean Pratt (Author)

Publication date: 04/13/2021

It's time for a new way to think about investing, one that can contend with the complex challenges we face in the 21st century.

Investment today has evolved from the basic, conventional approach of the 1950s. Investors have since recognized the importance of sustainable investment and have begun considering environmental and social factors. Yet the complexity of the times forces us to recognize and transition to a third stage of investment practice: system-level investing.

In this paradigm-shifting book, William Burckart and Steve Lydenberg show how system-level investors support and enhance the health and stability of the social, financial, and environmental systems on which they depend for long-term returns. They preserve and strengthen these fundamental systems while still generating competitive or otherwise acceptable performance.

This book is for those investors who believe in that transition. They may be institutions, large or small, concerned about the long-term stability of the environment and society. They may be individual investors who want their children and grandchildren to inherit a just and sustainable world. Whoever they may be, Burckart and Lydenberg show them the what, why, and how of system-level investment in this book: what it means to manage system-level risks and rewards, why it is imperative to do so now, and how to integrate this new way of thinking into their current practice.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

It's time for a new way to think about investing, one that can contend with the complex challenges we face in the 21st century.

Investment today has evolved from the basic, conventional approach of the 1950s. Investors have since recognized the importance of sustainable investment and have begun considering environmental and social factors. Yet the complexity of the times forces us to recognize and transition to a third stage of investment practice: system-level investing.

In this paradigm-shifting book, William Burckart and Steve Lydenberg show how system-level investors support and enhance the health and stability of the social, financial, and environmental systems on which they depend for long-term returns. They preserve and strengthen these fundamental systems while still generating competitive or otherwise acceptable performance.

This book is for those investors who believe in that transition. They may be institutions, large or small, concerned about the long-term stability of the environment and society. They may be individual investors who want their children and grandchildren to inherit a just and sustainable world. Whoever they may be, Burckart and Lydenberg show them the what, why, and how of system-level investment in this book: what it means to manage system-level risks and rewards, why it is imperative to do so now, and how to integrate this new way of thinking into their current practice.

CHAPTER ONE

Set Goals

LEO TOLSTOY, the famed Russian writer, penned a fairy tale in 1899 called The Big Oven that feels very prescient for today. The story is about a man who has a large oven to heat his large home, though only he and his wife live there. He starts to run out of firewood in the worsening Russian winter. Ignoring the suggestions of neighbors to conserve by getting a smaller oven, he instead feeds it all the wood available to him, including the wood from his fences, his roof, and his ceiling. He eventually tears down his whole home in a vain attempt to keep it heated and has to ultimately go live with strangers—all because he was unwilling to face the fundamental problem and actually fix it, settling for short-term band-aids instead of a cure.1

We’ve heard that we’re “burning down the house” by underreacting to climate change, and the same could be said for the finance industry. We’ve already seen how a myopic focus on the here and now has hurt us—how the oven of investors’ focus on maximizing short-term returns is burning through social and environmental fuel at an unsustainable rate. Put another way, today’s conventional management goals, as useful as they may be at producing profitable portfolios, come up short when confronted with broad threats to our social, financial, and environmental systems and indeed often unintentionally contribute to these challenges.2

This chapter shows why setting initial goals at a system level is crucial to avoid burning down the house; examines the initial goals conventional, sustainable, and system-level investors set for themselves; and explains the need for formulating goals at a system level.

Conventional Investors’ Focus: Maximizing Returns

Elaborated from 1953 through 1972 and put into practice starting in the late 1970s, modern portfolio theory (MPT) was a true revolution in finance. It built on well-established practices that focused on avoiding individually risky securities and put them in the context of sophisticated disciplines for managing risks and rewards at the portfolio level. Fundamental to MPT were a number of axioms, such as the benefits of diversification, the efficiency of markets, and the correspondence of risks taken to rewards received. MPT also assumed that systematic risks—that is, those inherent in the market or in an asset class as a whole—are beyond the ability of asset owners and managers to influence. They therefore should not be penalized or given credit for portfolio losses or gains due to the “systematic” rewards or risks of the market as a whole but only for their own “idiosyncratic” contributions to their portfolios’ performance, positive or negative, relative to that of the market.

The long-standing use of MPT speaks to its many advantages. Nevertheless, academics and practitioners in the investment community have recognized that MPT is not without its limitations. Its theoretical constructs assume, for example, that markets operate without transaction costs, have unconstrained liquidity, have a risk-free investment option always available, and are composed of rational actors who consistently act in their own best interest.

Most important, though, is the assumption that the market has risks and rewards that affect investors but that they themselves cannot influence. Whether they are individuals plotting future retirement or institutions addressing future liabilities, the only value that investors can claim for themselves is adding to their portfolios returns that are over those coming from the market as a whole. They only get credit for beating the market—or take the blame if they can’t do so.

The global financial crisis of 2008 shook the unquestioning faith in that basic idea. Were not investors’ own practices—and their faith in diversification to always protect them from risks—in large part responsible for this global meltdown? Didn’t investors’ own actions at least in part disrupt the financial system with disastrous consequences? Shouldn’t they be held responsible for the damage they were doing? And if so, couldn’t investors just as easily inflict the same kind of damage on social and environmental systems and be held responsible for that as well?

At the same time, the financial services industry’s size and wealth were growing almost inconceivably. In an increasingly populous and prosperous world of 7.8 billion as of 2020—with rapidly advancing economies in the developing world and increasingly powerful technological tools in ever-increasing availability—estimates of total wealth worldwide in 2019 now run at over $360 trillion.3

This substantial size of the financial services industry, both relative to others and in absolute terms, endows its collective actions with an enormous potential for creating unintentional harm. It is only natural that new goals beyond the maximization of portfolio returns by beating the market have emerged as well.

Sustainable Investors’ Focus: Social and Environmental Factors

The growing size of the financial markets relative to the overall economy and the diminishing role of governments in regulating those markets have led some investors to intentionally create portfolios with environmental and social benefits. Sustainable investors believe integrating social and environmental considerations into their investments can add value both to society and to their portfolios. When poorly managed, ESG considerations can introduce risks to both; when well managed, they can produce benefits. When these investors consider ESG issues in their decision-making, they might, for example, steer clear of companies that face distracting and costly gender discrimination legal battles, those with frequent sexual harassment lawsuits, or firms that perpetuate dangerous working conditions in developing countries. Alternatively, investors might believe that renewable energy sources (e.g., wind, solar) will replace fossil fuels and invest in them as an attractive long-term investment opportunity.

So, what do sustainable investors care about? There are numerous issues that they might want to address through their investments, and these issues affect industries differently. But they are most likely to encounter certain ones.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), for example, provide a useful framework for sustainability issues. Asset managers now frequently reference these goals in marketing and communication materials, in part due to investors’ interest and demand. Although some investors and managers have embraced the goals more enthusiastically than others, most will nonetheless acknowledge them.

The seventeen SDGs together target 169 outcomes. These goals can be organized as broad thematic groupings: people focuses on ending poverty and hunger and promoting health, equality, and education; planet refers to protecting the earth from degradation; prosperity aims to ensure that all lives are fulfilling and prosperous; peace focuses on “peaceful, just and inclusive societies”; and partnership refers to the participation of “all countries, all stakeholders and all people” in achieving the goals.4

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Materiality Map provides a similar framework for determining sustainability issues. An independent organization that sets standards for corporate ESG disclosure, SASB assesses and maps the materiality impact of noteworthy ESG issues across key industry sectors. It does so with an eye to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s reporting regulations using a thorough research and vetting process.

SASB has identified thirty issues as reasonably likely to affect the financial condition or operating performance of a company. Its Materiality Map assesses the extent to which relevant issues affect financial performance for ten industry sectors and their key subsectors. These include environmental capital issues like greenhouse gas emissions, energy management, and water and waste management; social and human capital issues like access and affordability, customer welfare, labor relations, and fair labor practices; and governance issues like business ethics and transparency of payments, regulatory capture, and political influence.

System-Level Investors’ Focus: Health and Stability of Society, Capital Markets, and the Environment

Conventional investors focus on the efficiency of portfolios to maximize returns that result in long-term utility to society. Sustainable investors focus on generating social and environmental benefit along with financial returns. Both approaches stop short of providing a way for investors to strengthen social, financial, and environmental systems.

In the last fifty years, population growth has increased the labor supply at the same time that a rise in global prosperity and investable assets has increased capital. All this increased growth in labor and capital, along with the economic interconnections they have brought with them, has taken place on a planet with limited resources—that’s the one thing that hasn’t changed and won’t change. The oft-cited remark that “anyone who thinks that you can have infinite growth in a finite environment is either a madman or an economist” rings truer today than ever before.

Investors therefore find themselves in the difficult situation of having to seek the ideal point at which their efficient allocation of assets still functions positively but without harming or otherwise disrupting fundamental systems. Or, in Herman Daly’s precise economic language, “The rule is to expand scale (i.e., grow) to the point at which the marginal benefit to human beings of additional man-made physical capital is just equal to the marginal cost to human beings of sacrificed natural capital.”5 The scale of our efficient economy can now cause many of our crucial systems to become fundamentally unstable in ways previously unimaginable.6

The Three Sets of Systems Ripe for Instability—and Opportunity

One dramatic example of this instability is the impact of COVID-19. Officially designated a global pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, COVID-19 led to substantial declines in international travel (and domestic travel in some countries), forced closures of schools and “nonessential” businesses, overwhelmed health systems, and brought economic activity in most parts of the world to a near standstill.7

COVID-19—and its associated social and economic fallout—shows how social and financial systems (including their underlying business models and supply chains) have become so globalized and interdependent that a disruption to one can wreak havoc on others. Although finance cannot prevent the threat of the next pandemic, intentional system-level decision-making by investors can help prepare for it and mitigate its worst social and economic impacts.

We need better guardrails. By taking a few decisive steps, investors can help put these in place. Investors need to support governments resilient enough and with deep enough pockets to build safeguards and kindle economic recoveries, insist that companies understand their business models and prepare backstops to prevent their meltdown, and prepare for potential systemic breakdowns. With the right tools, investors have the ability to help stabilize these systems while also making long-term, profitable returns.

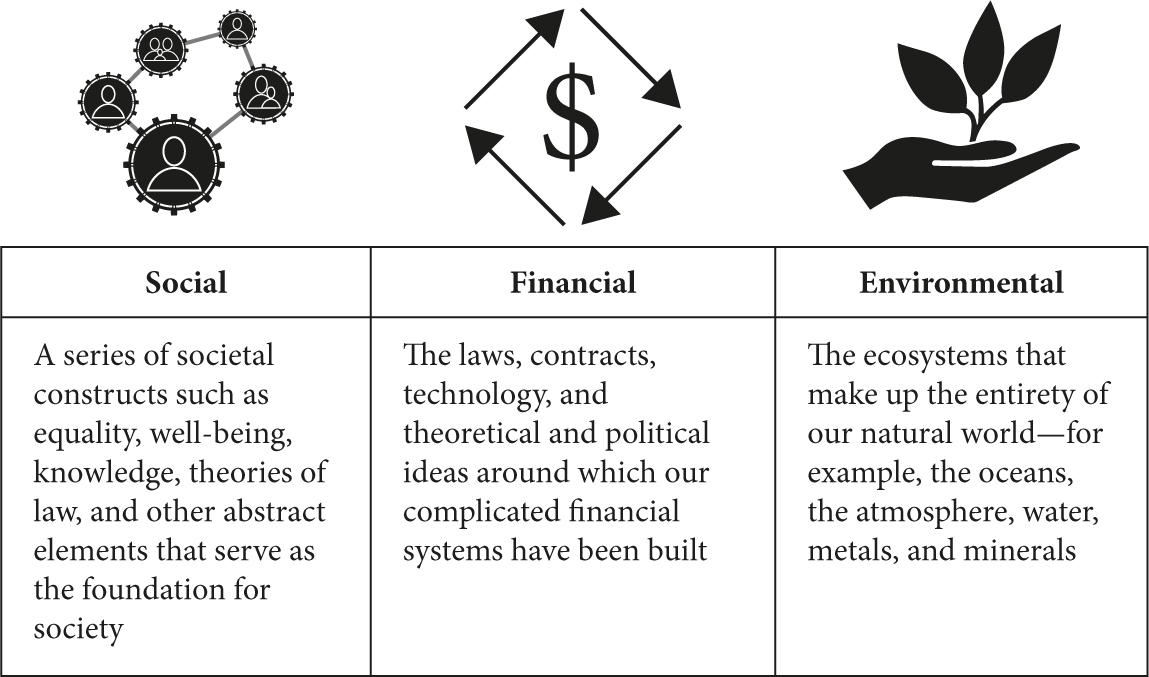

Three major systems today can benefit from intervention by investors. These systems—social, financial, and environmental—have the potential for high instability, leading to another crash or worse.

Social Systems

Several major corporate trends have created social inequities over the past several decades. They include the maximization of short-term profits at the expense of labor, the tying of CEO compensation to stock price performance, and the movement away from the responsibility for paying a “fair share” of taxes.8 These shifts have occurred with little regard to their external costs to society or their opportunity costs for the support of basic social and environmental systems, infrastructures, and stakeholders on which sustainable profits and returns ultimately depend.

The relationship between extremes in income inequality and social and political crises is one that investors Ray Dalio, Steven Kryger, Jason Rogers, and Gardner Davis examined in their research on the phenomenon of populism.9 Key to their findings is that the kind of populism that emerged in the world at the turn of the 20th century and in the 1930s (the periods before and between the two world wars) is analogous to that of today.10 Extremes like those experienced in those times can lead to conflicts that “typically become progressively more forceful in self-reinforcing ways” and that “often lead to disorder (e.g., strikes and protests)” within countries. They in turn lead to an erosion of democratic governance and the rise of dictatorships.11 The verdict is still out on how extreme populist sentiments will grow in the coming years, but they are currently manifesting through things like inequality in wealth distribution to a degree rarely seen before; structural unemployment—particularly among the young—that appears to be more than temporary; and winner-take-all industries where a handful of behemoths dominate global markets and take the lion’s share of profits.

The importance of inclusive growth is key in the discussions about income inequality and serves to reinforce the wide-ranging agreement about the potentially destabilizing effect the issue has on overarching systems. The International Labor Organization (ILO)—the United Nations agency focused on addressing labor issues globally—has emphasized this dimension in its calls for support for social justice. The growth in inequality, according to the ILO, has not only led to declines in productivity and helped to breed poverty, social instability, and conflict but also led the international community to recognize the need for basic “rules of the game” to ensure globalization promotes equitable prosperity for all.12

Some investors are heeding this call and leveraging their assets to promote equal access to a variety of industries for the historically underserved, including digital technology (bridging the digital divide), healthcare (Access to Medicine Index, which reports how twenty pharmaceutical companies make medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics more accessible for people in low- and middle-income countries), financial services (microfinance), and mobile telecommunications.13

Still, the siren call of the short term prevents many investors from joining in newer, less conventional endeavors with their long-term benefits to the system as a whole. What investors all must acknowledge is that a long-term view—not bowing to short-term returns over all else—makes it easier to predict and mitigate the nature and extent of the global disruptions to come.

Financial Systems

Scale and short-term profit taking also pose challenges in our financial systems. The lending practices of the early 2000s, with their “robosigning” and packaging of questionable mortgages into diversified fixed-income securities and the willingness of investors around the world to purchase these bonds, were among the root causes of the 2008 financial crisis.14 In that case, the financial community was placing blind faith in the markets to price securities accurately. In the words of Amar Bhidé, this reliance on the efficiency of financial markets to price is a bit like “driving blindly.” As he argues in his book A Call for Judgment, “the absolutist prescription to forsake judgment” in assessing financial transactions because one has faith in the efficient pricing of securities has led us

to blindly trust market prices, [which] not only puts those who follow it at risk, but also undermines the pluralism of opinions that help align prices and values. . . . Forsaking case-by-case judgment . . . is unsustainable en masse: If everyone eschews judgment, who will make market prices even approximately right, or ferret out the offerings of thieves and promoters of worthless securities? Paradoxically, the efficiency of securities markets is a public good that can be destroyed by the unqualified faith of its believers.15

Similarly, Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik, and David Pitt-Watson, in their book What They Do with Your Money, argue that what appear to be innovative financial services creating efficiencies in a complex system have now become at best a drag on the economy and at worst a destabilizing wild card in a system that they believe is “built to fail, at least if success is defined as efficiently promoting our interest.”16

Since 2008, numerous governmental regulators, industry experts, academics, and public interest groups have proposed stabilizing remedies for this often-abused system. The need for a more active role by government—“adult supervision”—is clear if today’s financial system is to better serve the public interest. Evaluating these numerous proposals for government’s role is beyond the scope of this book. Many others are tackling that challenge. Rather, we suggest that investors’ increasing focus on universal ownership, investment stewardship, long-term value creation, impact investing, ESG integration, and standards setting may play a supporting but essential role to ongoing regulatory measures, lend much-needed stability and a long-term perspective to the financial system, and steer it away from its habits of abuse.

Environmental Systems

When it comes to environmental systems, investors’ obsession with short-term efficiency can, and increasingly does, lead to destruction of long-term environmental value.17 Fossil fuels have long been the most efficient and reasonable energy source. But the scale has now tipped from useful to destructive. Before the 2020 pandemic hit, the global economy burned or otherwise consumed more than 100 million barrels of oil a day, not to mention its use of coal and other fossil fuels.18 These natural resources have brought tremendous economic benefit without which much of the economic progress since the late 19th century would not have been possible. But this very efficiency is now threatening to destabilize what have been the earth’s relatively stable environmental conditions over the past ten thousand years, conditions that have made civilizations as we know them possible.

Tricky challenges like these have been dealt with successfully before. Thirty years ago it became clear that chlorofluorocarbons—Freon and similar gases—were causing damage to the ozone. In 1987, the world adopted the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion. Kofi Annan, the one-time secretary general of the United Nations, referred to the protocol as “perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.”19 The result is that the ozone hole in Antarctica has slowly recovered, and the ozone layer is expected to return to 1980 benchmark levels in the coming decades.20

Scientists point to other looming challenges on environmental fronts. The Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC), for example, frames these challenges in terms of “planetary boundaries” beyond which unpredictable, catastrophic changes take place. Beyond a certain point, our efficient activities run the risk of fundamentally changing the nature of the earth’s environmental systems—nine of them, according to SRC—in ways that we cannot predict but that will cause profound disruptions.21

Just as society had to face the unpredictable consequences of the potential destruction of the earth’s protective ozone layer from our globally efficient use of Freon, it must now contend with the far more complex task of phasing out fossil fuels to avoid equally problematic uncertainties. But even when the phaseout of fossil fuels is achieved, the underlying problems remain the same: the impacts of scaling up in a populous, interconnected global economy.

These challenges are one of the ways the 21st century will differ from the 20th, and we have to expect and push finance to face these challenges head-on.

Setting System-Level Goals

Three overarching systems, shown in figure 1, require system-level interventions that are highly complex and interconnected. Fortunately, the broad adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals has created an opportunity for investors to think more broadly about their investment goals while also developing concrete investment strategies. Instead of focusing on a simple enumeration of achievements tied to specific investments (e.g., number of affordable housing units created, kilowatts of energy saved, this or that corporate policy changed), they can instead work toward achieving these overall system-level goals.

System-level investors push themselves to achieve goals that focus on the paradigms operative at system levels. Paradigms are “philosophical and theoretical frameworks within which we derive theories, laws and generalizations.”22 As a driving force within complex systems, paradigms are a primary contributor to the output of the system. To change the output of a system with a reasonable degree of consistency, one often must change the paradigms that it operates under. The more fundamental a paradigm shift, the more likely the system is to consistently produce a different output. Using one of the SDGs as an example, investing in the area of planet would require a goal of shifting the paradigm of global reliance on fossil fuels.

Figure 1. Three overarching systems

But a single investor, no matter how large, cannot bring about paradigm shifts alone. Within a complex system, multiple actors and factors are inevitably in play. A causal relationship between a specific investor’s input—or any other single factor—and a fundamental paradigm shift is difficult to demonstrate. Influence by multiple parties, however, in bringing about system-level change is a more achievable goal.

For example, in 2017 the Global Investor Coalition on Climate Change, comprising more than 373 investor-members around the world with $35 trillion in assets under management, launched Climate Action 100+, a five-year project committing investors to collaboratively engage more than one hundred of the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters to reduce their carbon emissions. Through this broad-based effort, it is focusing on the largest emitters to increase its chance of shifting practices—and the working paradigm for corporations in general—to substantial reductions of these emissions.23 Among the members of its steering committee are AustralianSuper, California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), HSBC Global Asset Management, Ircantec, and Manulife Investment Management.

In its initial 2019 progress report, the coalition noted that its members had already negotiated agreements with major corporations such as AES Corporation (70 percent reduction in carbon intensity by 2030), HeidelbergCement (net zero emissions by 2050), Maersk (net zero emissions by 2050), Nestlé (net zero emissions by 2050), Rio Tinto (exited from coal mining), Volkswagen (climate neutral by 2050), and Xcel Energy (zero carbon electricity by 2050).24

The report also sets baseline metrics for measuring future progress. It notes, for example, that companies in most industries have a board member or committee with clear responsibility for climate change—for example, oil and gas (85 percent), industrials (73 percent), and utilities and power producers (74 percent). Relatively few, however, “ensure consistency between their climate-change policy and the positions taken by industry associations of which they are a member”—oil and gas (8 percent), industrials (4 percent), and utilities and power producers (3 percent).25

To set goals with relation to paradigm shifts, investors will need to start with an assessment of the current paradigms relating to the system-level challenges with which they are concerned and develop a vision of what alternative paradigms would produce fewer problematic results. With a clear definition of both old and new paradigms in mind, investors can then develop with reasonable specificity goals and milestones for progress.

What Can Investors Do? Think Systemically

This shift toward thinking about the systems in which they invest requires a change in how investors structure their investments. Even those who rely on intermediaries—as most individuals who buy mutual funds or work with financial advisors do—can advance a system-level focus by choosing products and advisors who reflect this awareness.

Investors interested in system-level investing can rely to a certain extent on the techniques developed in the latter half of the 20th century for managing portfolio risks and rewards, but they need a more comprehensive understanding of the effect of these investments on the environment and society. A 2015 report from the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, for example, found that “changing asset allocations among various asset classes and regions, combined with investing in sectors exhibiting low climate risk, can offset only half of the negative impacts on financial portfolios brought about by climate change.”26 It’s clear that just excluding industries and avoiding bad actors is only half the battle. Investors also need solutions.

By paying attention to the feedback loops between investment practice and social, financial, and environmental systems, system-level investors can set goals that contend with threats that conventional and sustainable investing often ignore. In doing so, these investors acknowledge their impacts on the economy as a whole; their responsibility for stewardship of systems that have been built up over decades, centuries, and eons; and their ability to create long-term value, pursue profit with a purpose, and set social norms. This is a challenge but one that can be overcome by those adopting a new mindset and the right techniques, as we will show in the following chapters.