Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

A Human Resources Framework for Public Sector

Dixon Southworth (Author)

Publication date: 03/01/2009

What makes a good worker? Why do some people naturally do well at their jobs while others struggle? These questions are at the heart of the human resource (HR) profession. And while there is no shortage of theories about how people achieve success, no one has explained the entire body of HR theories. Until now.

In A Human Resources Framework for the Public Sector, Dixon Southworth offers a fresh, new perspective on HR management with the first comprehensive theoretical framework for work performance, tying human resource theories, concepts, and concerns to public administration. With the introduction of the Work Performance Framework (WPF), Southworth offers a roadmap for work performance in the nonprofit and public sectors that focuses on three fundamental objectives of HR programs and services: build human resource capacity, build performance, and build community.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

What makes a good worker? Why do some people naturally do well at their jobs while others struggle? These questions are at the heart of the human resource (HR) profession. And while there is no shortage of theories about how people achieve success, no one has explained the entire body of HR theories. Until now.

In A Human Resources Framework for the Public Sector, Dixon Southworth offers a fresh, new perspective on HR management with the first comprehensive theoretical framework for work performance, tying human resource theories, concepts, and concerns to public administration. With the introduction of the Work Performance Framework (WPF), Southworth offers a roadmap for work performance in the nonprofit and public sectors that focuses on three fundamental objectives of HR programs and services: build human resource capacity, build performance, and build community.

Dixon Southworth, MPA, is a consultant for the New York State Comptroller in the Office of Human Resources, where he is developing effectiveness and efficiency measures and measurement instruments for HR programs and services. He regularly applies the many aspects of the Work Performance Framework to his work. He was formerly a leader in the use and development of performance assessments for civil service examinations at the New York State Department of Civil Service.

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to the Work Performance Framework

This opening chapter introduces the Work Performance Framework (WPF) as a theoretical construct for work performance in public service. The framework merges human resource (HR) management theories, concepts, and concerns with public administration theories, concepts, and concerns. The WPF is a tool for HR managers and public administrators to use to manage work performance, for public-sector workers to understand and manage their individual and aggregate development and performance, for academics to provide instruction on public-sector work performance, and for researchers to identify new topics and lines of inquiry to explore.

THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF THE WORK PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK

The WPF is built upon recent literature on public administration theory and HR management theory. While the following literature review does not account for all pertinent theoretical research and discussion in the areas of HR management and public administration, these works were instrumental in the construction of the WPF.

Public Administration Theories

We need a comprehensive theoretical framework to better understand the profession of public administration. If there have been shortcomings in the search for such a framework, it is not for lack of trying. A vast number of books, journals, papers, and conference proceedings abound with discussions, frameworks, formulas, data, statistical analyses, and case studies. Nonetheless, there is still little agreement about what public programs are supposed to accomplish, and there is no universally acknowledged theoretical framework.

R. D. Behn (1995) proposed that scholars in public management entertain big questions, much like those in science. Comparing the “science” of public administration to physics, where questions like the origin of the universe led to the big bang theory, he notes that scientists do not start with data or methods; they begin with questions. Once a big question has been set, the data and methods are developed to achieve the goal. Behn’s three big questions for the field of public administration ask how to manage public programs without micromanaging, how to motivate public-sector workers to achieve public purposes, and how to measure agency achievements in a way that leads to greater success. A theoretical framework on work performance would be extremely helpful in addressing Behn’s three big questions.

J. C. N. Raadschelders (1999) documented the need for a comprehensive theory of public administration, explaining that the field suffers from identity confusion due to existential and academic crises. He explains that public administration’s existential problem stems from the need to separate itself as an independent discipline apart from political science, economics, and business administration. The academic problems, in his view, stem from epistemological questions that must be addressed by applying organizational theories to public organizations, relating theories of human action to the practice of governing, and addressing the extent to which our knowledge of public administration is scientific. Although he does not take on these challenges himself, Raadschelders does present a diagram of public administration as a body of knowledge, cataloging topics of discussion under four quadrants (what, who, why, and how) that are the foundation of the general question: what is public administration?

In The Spirit of Public Administration (1997), H. George Frederickson argues there should be three pillars of public administration theory—efficiency, economy, and social equity. In positing a compound theory of social equity, Frederickson uses the terms fairness, justice, and equity interchangeably, where the ultimate goal of social equity is a more equal distribution of opportunities, costs, and benefits. The basis for this activity is that public administrators should be good citizens who benevolently oversee public programs and actively seek to help the less fortunate.

At the 2001 national conference of the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA), this author presented a theoretical framework for public programs. The framework for public programs, which has been incorporated into the WPF, aligns with Frederickson’s three pillars for public administration but includes some subtle differences.

The framework for public programs begins with the central premise that public programs must follow one ethical rule: neither provide nor charge for unnecessary services. This premise is analogous to the “invisible hand” that ensures efficiency in free enterprise markets. And it leads to the fundamental question: what is the purpose of public programs? Two fundamental purposes of public programs are (1) public programs must provide important services that should not and cannot be provided by private businesses, and (2) government is responsible for advancing social justice.

The framework for public programs identifies three public program service components: (1) prevent or solve societal problems; (2) provide care and compassion; and (3) through the distribution of information and other resources, enable people to solve their own problems.

The framework also proposes four social justice components of public programs: (1) equitable laws and procedures that create a level playing field on which people who are motivated to do their best can enjoy substantial individual rewards; (2) generous distribution of our nation’s wealth to all citizens, especially the most needy; (3) due process procedures that provide a mechanism for citizen dissent; and (4) a social contract that holds people accountable for being responsible citizens and for helping themselves to the fullest extent possible when aided by public programs.

The intended impact of these public programs is to advance the belief among our citizens that (1) public programs provide important value; (2) the programs are fiscally responsible; (3) the programs balance individual rights and benefits against rights and benefits for all; and (4) because of these programs, our government is good. Thus, we have constructed a working definition of goodness, so “good” public programs are efficient, effective, and fair. (By extension, the “good” public-sector worker is also efficient, effective, and fair.)

Finally, the framework for public programs posits that the desired sustainable result of public programs is social harmony.

Human Resource Management Theories

S. E. Jackson and R. S. Schuler (1995) identify a number of contemporary theories that aid an understanding of HR management within the context of the organization. The authors describe the role-behavior perspective, institutional theory, resource-dependent theory, human capital theory, transaction costs theory, agency theory, resource-based theory, and general systems theory. These theories range from evaluating the cost and value of HR management to identifying the interpersonal and social systems that occur in organizations, which workers must understand in order to maneuver effectively. Wright and Snell’s management model (1991) uses general systems theory. Skills and abilities are presented as inputs, employee behaviors are presented as throughputs, and employee satisfaction and performance are outputs.

H. P. Hatry (2001) describes an adapted United Way model for human services programs in which program outcomes encompass “new knowledge,” “increased skills,” and “changed attitudes or values,” which lead to “modified behaviors,” which in turn lead to “improved conditions” or “altered states.”

Other HR management systems theories add aptitudes and personality traits as inputs in addition to knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) and add work duties, work activities, and tasks as processes in addition to work behaviors.

By incorporating many of the HR management topics discussed by Hatry and by Wright and Snell, the WPF adopts general systems theory as the basis for constructing a comprehensive theoretical framework for HR management. By addressing the public administration topics presented by Behn, Raadschelders, and Frederickson, as well as this author’s line of inquiry into public programs, the WPF merges HR management theory with general public administration theory.

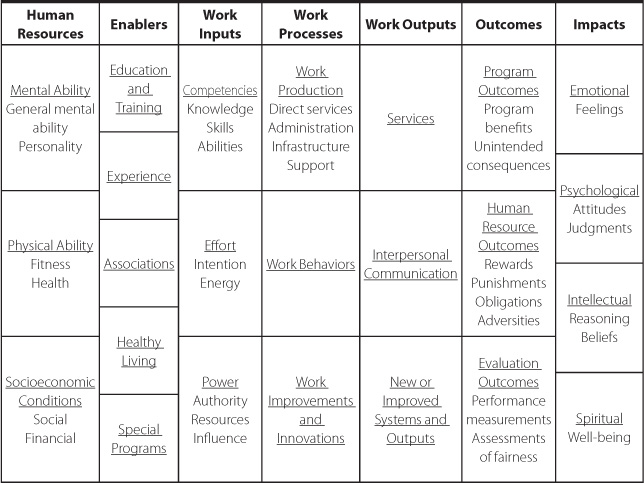

OVERVIEW OF THE WORK PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK

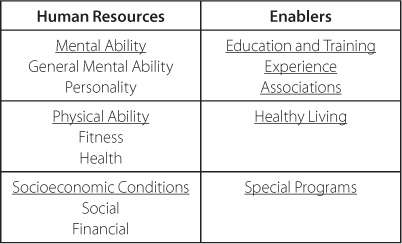

The WPF as a theoretical framework for work performance in public service contains three parts. The first part, consisting of human resources and enablers, addresses the antecedents to work performance, which include raw human resources and the enablers that transform these raw human resources into work inputs. The second part, consisting of work inputs, work processes, and work outputs, addresses actual work performance in a public-sector setting. The third and final part, consisting of outcomes and impacts, addresses the aftereffects of work performance, including public program benefits, HR outcomes, and the impacts of work performance and public programs on workers and other stakeholders. Table 1-1 presents an overview of the WPF.

TABLE 1-1 Work Performance framework

Human Resources and Enablers

In the WPF, human resources are identified as potential abilities; they are differentiated from applied abilities, including competencies or KSAs, which are presented as inputs. Potential abilities pass through an enabling process and become applied abilities at the time work is performed. Human resources and enablers, presented in Figure 1-1, precede inputs and are not a part of general systems theory.

FIGURE 1-1 Work Performance Framework—Human Resources and Enablers

Human Resources

People begin their quest for achievement with certain mental abilities, physical abilities, and socioeconomic conditions. These resources help to determine the training and development opportunities that are accessible to them, and ultimately which ones they select. These opportunities enhance their prospects for employment and career success. For example, a person with strong mathematical abilities might choose to study engineering and subsequently enter the workforce as an engineer armed with professional engineering KSAs.

Mental abilities are the capacity or capability to perform certain mental activities and include general mental ability represented as g, personality, aptitudes, talents, wisdom, creativity, and charisma. While these abilities are not job-ready, people with greater mental abilities are more likely to learn and understand information presented through education or training, or from on-the-job experience. General mental ability, or g, is considered one of the most reliable predictors of job performance. Nonetheless, it is far from a perfect predictor.

Physical abilities are included as a resource primarily to address effort as a factor of work performance. High performers not only have the mental capacity to deal with complex work situations; they must also have the energy to remain positive and effective under the adverse conditions of long workdays, strained relationships, in-fighting, shortened deadlines, and failing ventures. To offset the possibility that physical ability might be given too much importance in hiring, the Americans with Disabilities Act affords certain protections to people with physical or mental disabilities from employers who would discriminate against a disabled person.

While there is a legitimate interest in hiring energetic people, employers cannot leap to the conclusion on face value alone that a person with a disability necessarily has a low energy threshold or work limitation. Physical ability requirements are also important for security-related positions. Police officers and firefighters, for example, must use their physical abilities to save lives.

Socioeconomic conditions are influential in regard to work performance and likelihood of success. Wealthy people can afford to buy opportunities by, for example, living in the better school districts with better teachers and attending the expensive and exclusive colleges and universities with top-ranked faculty, enormous resources, and networked employment opportunities. Meanwhile, those with moderate or low incomes are often denied these advantages, live in the poorer school districts with fewer resources, and attend technical schools or state-operated colleges or universities, or they have no advanced education at all. Although the advantages of wealth do not absolutely predict individual outcomes, they clearly affect the odds.

In the public sector, helping the underprivileged is especially important. Frederickson defines the goal in terms of social equity, i.e., redistributing wealth to the needy. While some people may take a very conservative view of the government’s role in redistributing wealth, it is clear that helping the needy is an ideal embraced by our society as a whole, so the issue of socioeconomic conditions must be addressed within the WPF.

Enablers

The enablers described in the WPF complete the transition of human resources (mental abilities, physical abilities, and socioeconomic conditions) to work inputs (competencies, effort, and power). How does a mental ability become a competency? How does physical ability become effort? How do we help underprivileged people become valued employees? The enablers do it, and they are well known—education, training, experience, exercise, healthy living, and special assistance for those who need it.

Education, in particular higher education, addresses the inputs of professional and technical competencies to enable a person to become, say, a computer analyst, engineer, teacher, lawyer, doctor, or registered professional nurse. At the community college level, a person might become a technical expert such as a plumber, automotive technician, electrician, or licensed practical nurse, while four-year college and graduate-level programs tend to reflect professional-level jobs. Educational programs in public or business administration are available to obtain competencies in management and administration.

Training programs often address competencies related to staff supervision and operational information on pertinent laws, rules, regulations, policies, and procedures. Training programs may also target competencies related to interpersonal relationships, oral presentation, special computer software used by an organization, and customer-service procedures and techniques.

Experience can be gained directly through appointments and promotions, or indirectly through special assignments, internships, or even volunteer work. Such experience can be valuable in developing interpersonal skills and influencing techniques in a work environment, delegating work to others and monitoring their performance, and managing workload. A vital part of on-the-job experience is guidance through mentoring and coaching, which can help maximize the likelihood of a successful work opportunity.

Exercise and healthy living programs are often recognized by the organization as popular with employees and beneficial in reducing employee sick days, but the primary benefit is to increase energy, strength, and stamina to help workers withstand high work demands.

Special assistance includes affirmative action programs that provide employment opportunities to women, minority group members, and disabled workers to help them succeed and advance in the organization. To avoid accusations of reverse discrimination, individuals often targeted for special assistance include the needy population or those people who are socially or economically disadvantaged. An employee assistance program (EAP) in an organization helps employees with special problems navigate through their difficulties without negatively affecting their work performance.

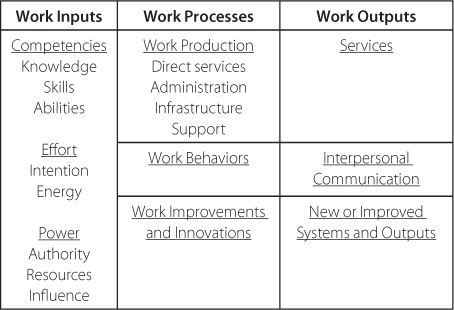

Work Inputs, Processes, and Outputs

Work inputs, processes, and outputs are classic elements of general systems theory; they are the center of the WPF. Figure 1-2 presents inputs, processes, and outputs in the WPF.

FIGURE 1-2 Work Performance Framework—Work Inputs, Processes, and Outputs

Work Inputs

People as inputs are presented as a combination of competencies, effort, and power. Within the WPF, competencies are identified as applied abilities once actual work is performed, and are differentiated from potential abilities, which, as explained earlier, go through an enabling process.

Traditional civil service examinations concentrate on competencies, often identified as KSAs. Personal attributes are also sometimes presented as inputs and evaluated by special screening devices such as personality tests, psychological tests, and integrity tests. Competencies are included in the WPF as an input, although they too can go through an enabling process.

For the purpose of developing civil service examinations, KSAs can be broken down into several general categories:

• Professional or technical

• Operational

• Administrative, managerial, and/or supervisory

• Computer

• Reasoning and decision-making

• Oral presentation

• Customer service and interpersonal relationships.

These categories are also helpful when linking duties to KSAs during job analysis.

The WPF also includes two other elements—effort and power—as input variables. The reasoning is that a person might have the competence to work, but might not put in the effort. Or a person might properly apply her competence to a work assignment with sufficient effort, but if she is not empowered to act, the assignment may be blocked from completion. Sometimes a person attempts to act anyway by assuming the authority to act, thus having de facto power. When things work out well, this may be a feather in our cap, but if things go wrong, we can be subject to punishment for misconduct.

Effort can be broken down into two categories: intention and energy. There are many HR theories related to employee intentions, such as motivation and self-efficacy. But good intentions are not enough; one must also have the energy, i.e., the strength and stamina for a demanding work schedule. Effort includes both physical and mental energy, particularly when work is performed under adverse conditions. Often, adversities—such as personality conflicts, abbreviated deadlines, long days, or dangerous situations—require a great deal of strength and stamina, and often people decline promotions because they are not willing to take on the burden of these adversities.

Power is divided into three categories: authority, resources, and influence. Authority includes the permission that can come with job title, work duties, span of control, special assignments, and special projects. Power also includes access to the financial, capital, or staff resources needed to complete the work. Influence refers to the capacity to influence others.

While a person may have access to needed resources and jurisdiction over decision-making, to wield power effectively one must be able to influence others to act according to plan. Competencies aligned with influence include interpersonal skills, communication skills, and sound analysis and decision-making skills. These competencies are often evaluated by oral tests and assessment centers. Effort can also be a key part of influencing others. Lethargic leaders are unlikely to inspire or influence staff in a positive way.

Work Processes and Work Outputs

Work processes are the actions that people go through to produce work outputs. To understand and appreciate the processes, one must also understand the outputs. In the WPF, processes fall into three areas: (1) production, (2) behaviors, and (3) improvements and innovations. Production outputs include products, services, and information, although in the public service most outputs are services or information pertaining to the services. Work processes aligned with production include the normal work duties, activities, and tasks that appear in a job description. Performance standards often relate to product or service quality, efficiency, and reliability.

Work behaviors have often been linked with work activities, and some theorists use the two terms interchangeably. The WPF separates these two processes and presents a separate output—interpersonal communication—for work behaviors. Performance standards for interpersonal communication most closely align with trust and affiliation. Some confusion, which is addressed later in the book, arises from the fact that service is a production outcome, and trust and affiliation are important aspects of service quality.

Work processes related to improvements and innovations involve research and development, and the related work outputs are improved products, services, and systems. While some productivity gains can be made by improving work behaviors and work activities, the enormous gains in productivity over the last two decades have come from new and better work systems, particularly information systems. Information that was previously distributed by one person or one document can now be distributed throughout the world instantaneously via the Internet.

Ironically, as these systems do a better job of sharing information, demands and expectations for additional information often increase the workload instead of decrease it. Demands have been placed on computer experts since the beginning of this information revolution, and backlogs have required more scrutiny in tracking and prioritizing workload, budgeting, and outsourcing of work. Overall, we are seeing dramatic gains in work production and quality of life because of the information revolution.

By differentiating work inputs, processes, and outputs, the WPF provides some early indications as to why traditional examinations used to evaluate competencies are insufficient to account for the wide variation in work performance, and why a complete explanation of work performance goes well beyond any quick answer.

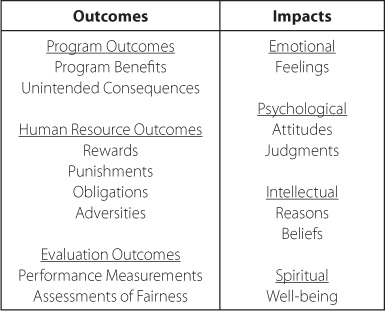

Outcomes and Impacts

In general systems theory, the outcomes and impacts of organizations are described as external results in the environment. Positive outcomes might include customer satisfaction or increased product sales, while impacts might be explained as the relative growth of the organization when compared to similar organizations. Outcomes and impacts of public programs might include the number or percentage of clients who entered the job market after completing a training program, and the resulting change in the unemployment rate.

Outcomes and impacts in the WPF are somewhat different from conventional thinking. Outcomes for a person within an organization include rewards (or punishments) that the worker receives from doing the work (or not doing it), and the impacts are the emotional, psychological, spiritual, and intellectual effects that these outcomes have on the worker. Thus psychology is very important to the study of HR management and work performance. Figure 1-3 provides an overview of these outcomes and impacts.

FIGURE 1-3 Work Performance Framework—Outcomes and Impacts

Outcomes

The WPF presents four sets of outcomes: program benefits and unintended consequences, rewards and punishments, obligations and adversities, and performance measurement and fairness. Unless an organization has a fair and accurate method for assessing performance, rewards and punishments will be subject to criticism. Thus, the need for civil service examinations to assess actual work performance, rather than just testing people for competencies, is perhaps the most revealing insight into effective public-sector HR management from the entire WPF.

Rewards are given for job successes and can be either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic rewards include job satisfaction, i.e., enjoying the work itself, and a pleasant work environment, which might include friendly people and comfortable surroundings. Extrinsic rewards include salary and benefits, promotions, special assignments, work opportunities, and the prestige or status that comes with the position.

Punishments are meted out for failures due to incompetence and for violations due to misconduct. Penalties can also be either intrinsic or extrinsic by reducing job satisfaction, salary, benefits, opportunities, or work status. Unfortunately, punishments are often in the eye of the beholder, so when a worker is not rewarded according to her expectations, she may view the outcome as a punishment. This phenomenon is especially visible where there are few promotions to hand out, and it often results in a person’s transferring to another assignment or leaving the organization altogether.

Obligations are inherent work responsibilities; they are different from expectations, where judgments are made about how well that person is expected to perform in the context of the assignment. Obligations can accompany both rewards and punishments. For rewards, a new promotion may mean that you are obliged to take on additional work or more responsibility. People who expect their work to be easier following a promotion are usually deluding themselves. Obligations related to punishments are those corrections necessary to ensure satisfactory performance, and they may be required as a condition of retention.

Adversities are also likely to accompany promotions and special assignments. The adversity of danger exists in such fields as law enforcement and fire protection, but there are also many less obvious adversities. There are personality conflicts and challenges to authority; there are time constraints from longer days, more deadlines, and a heavier workload that require time-management skills; and there are greater risks from greater responsibilities and potential failures that require risk-management skills. These adversities require mental and physical strength to resist criticisms and attacks. Often, these adversities lead people to believe that they may not be up to the job, so they decline the promotion or special assignment.

Performance measurement is presented as an outcome in the WPF because employers must evaluate how well a program met the organization’s goals, who should be rewarded or punished, and who can be expected to take on additional obligations and adversities.

When eligible lists are used for promotions and appointments in the public service, it is essential that the results are valid, i.e., the top performers appear at the top of the eligible list and vice versa. When eligible lists have low validity and utility, a no-win situation occurs, where managers look for alternative ways to reward the high performers and avoid promoting the low performers. Such actions often lead unions and disgruntled workers to make accusations of special treatment and unfairness. Problems are compounded by pressure for political favoritism to reward members of the political team that won office, further undercutting the credibility of the program managers.

Fair treatment has four components: equity, equality, due process and right to dissent, and the social contract. Equity requires that individuals receive special rewards based on special performance. Equality means that all workers are entitled to good benefits and respect. The right to dissent and due process procedures entitle the worker to present objections to the way she is treated based on claims of inequity—e.g., not receiving special rewards for special work—or inequality—e.g., not being well-treated as a member of the organization. Claims of unfair treatment are generally carried out according to union contracts, and unions may provide legal and technical services to their members to support their cases. Finally, the worker is expected to abide by the social contract—that is, because she has been given the benefits of equity, equality, the right to dissent, and due process, she is expected to be a good citizen of the organization.

Two other concepts go beyond the normal boundaries of fairness—generosity and mercy. Generosity requires us to help the needy and assist the underprivileged, not because they have earned the right for benevolent assistance but because of our humanitarian concerns.

Mercy is redemption; it affords a person a second chance. Some people make blunders that will forever prevent them from recovering under a system of strict merit and fair treatment. Only mercy offers the prospect of someone turning his or her life around and returning to the arms of society as an equal. Without the merciful act of a second chance, he or she may feel forever doomed. Even generosity and mercy have their limits, but the exceptional organization is the one that not only believes in fair treatment but also understands and practices generosity and mercy.

Impacts

Impacts are the emotional, psychological, intellectual, and spiritual effects that work outcomes have on the employee. It takes a great deal of fair and reliable treatment for an organization to gain the trust and affiliation of its workers, an exchange that works both ways. It takes a great deal of productive work and allegiance on the part of the worker to gain the trust and affiliation of the organization’s leaders.

Three impacts in the WPF are emotional, intellectual, and psychological reactions to work; they roughly parallel Freud’s mental structure of the id, the ego, and the superego. The fourth impact is the spiritual reaction that addresses the worker’s overall well-being. In the WPF the dominant impact is intellectual because the intellect takes into consideration our emotions, our judgments, and our well-being in order to develop beliefs about the world we live in. We then apply these beliefs when making life decisions.

APPLYING THE WORK PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK TO WORKFORCE PLANNING

The following overview of workforce planning shows how the WPF can be used as a tool for setting strategic HR goals.

Workforce planning has presented challenges for HR professionals ever since we realized that the baby boom generation would someday retire and test society’s ability to replace them in the workforce and provide for their benefits in retirement. To heighten the impact of the baby boomers’ retirement, people are living longer, and providing health care will present a major fiscal problem. Older workers must recognize that in 15 years or less, the value of fixed retirement income can be cut in half, so living longer will often translate to working longer. Retirees will need to decide how they can serve as active partners in the workforce, whether by volunteering or by working part-time. Public-sector organizations need to plan for increased services for older Americans, find a succeeding generation of workers, and use the talents of older workers to fill the HR gap.

In the past, workforce planning consisted largely of finding administrative support workers to process paper transactions—e.g., filing documents and other clerical work. Positions were classified en masse under a firm, consistent hierarchy, and tests for evaluating general mental ability were used to fill a broad range of government positions. Today, workforce planning is competency-driven: while general mental abilities have retained a credible role in employment test literature, organizations concentrate on recruiting people with specialized skills and abilities and use internal and external training programs to fine-tune those competencies.

Business records are now predominantly computerized, so filing documents and other clerical work have decreased or become unnecessary, and fewer support staff are needed. According to the New York State Department of Civil Service’s New York State Workforce Management Report 2006, the number of employees in the state workforce decreased from 178,757 in 1996 to 164,314 in 2006, a decline of 8.1 percent. The number of administrative support workers decreased by more than 25 percent during that period, from 36,804 to 27,489, accounting for nearly 2 out of every 3 jobs lost over that decade.

Clearly, planning for the future workforce is extremely important, but relying on past trends may not provide an accurate picture of future HR needs. HR managers must have a clear picture of what their organization wants to achieve in the future, and what human resources will be needed to reach their goals.

Desirable Human Resource Outcomes

To conduct workforce planning, the HR department must clearly define the outcomes it seeks. As a starting point for discussion, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) lists four categories for measuring the performance of HR programs in the federal government, along with descriptions of the categories and examples:

• Human Resources Operational Efficiency

• Measures of Legal Compliance

• Human Resource Management Program Effectiveness

• Strategic Alignment.

Operational Efficiency

An example of operational efficiency is the cost per discrete HR service—e.g., how much it costs, on average, to fill one position or train one person—or aggregated services—e.g., how much it costs to provide staffing services for all agency programs or train all agency personnel in one year. Total HR program costs as a ratio of all organizational costs is an efficiency measure that can be compared to similar organizations to determine whether total HR costs are higher or lower than they should be.

Another measure of efficiency is HR service processing time, or “cycle time.” For example, one measure of efficiency is the “position fill cycle time,” or the average amount of time it takes to fill a position from the time a request is made. By looking at service times, an analyst can identify which activities involve the greatest amount of staff time and which activities take the longest or shortest time to complete. For example, one might find that 80 percent of all recruitment and selection activities involve just 20 percent of all job openings. Thus, special attention can be given to reduce position fill cycle times for this 20 percent of job openings to maximize the cost-benefit return on HR processes.

Legal Compliance

Legal compliance involves meeting the requirements of all laws entitling workers, job applicants, or constituents to certain procedures or benefits. In the public sector, personnel actions such as appointments, transfers, leaves, and separations are processed in accordance with merit-system principles that involve specific requirements and supporting documentation.

Many of the complaints about “red tape” involve the documentation required to complete a personnel action. For example, after an appointment to a particular position is made, an HR staffer might have to document why another eligible candidate was not selected for the position. Explanations might include failure to respond to a canvass letter, declination based on job location, or temporary unavailability. Even though these requirements add time and cost to completing the appointment process, they guard against abuses and cronyism.

Program Effectiveness

HR program effectiveness relates to the benefits and unintended outcomes of these programs. Do the HR programs meet the needs of the organization and its program managers? Are program managers filling the positions that need to be filled? Are the workers getting the training they need?

Strategic Alignment

Strategic alignment means that the strategies and operations of the HR programs are aligned with the strategies of the organization, so the organization is able to meet its objectives, in part because the HR manager has set objectives and achieved performance goals that strengthen the organization.

Human Resource Service Objectives

HR service objectives can be constructed by comparing the OPM categories for performance measurement with the seven parts of the WPF. These objectives can be summarized as follows:

1. HR managers meet organizational staffing needs through position classification, recruitment, examination, selection, retention, and layoff programs.

2. HR managers meet employee development needs for the organization through traineeship, training, and development programs.

3. HR managers meet organizational performance management needs through programs for time and attendance, performance management, probation evaluation, performance evaluation, labor relations, and HR information systems.

4. HR managers meet organizational diversity, fairness, and legal compliance needs through the organization’s affirmative action program and by completing personnel transactions according to legal and procedural requirements.

5. HR managers meet employee benefits and rewards needs for the organization through its promotion examinations, payroll services, employee benefits, workers’ compensation, and employee recognition programs.

6. HR managers meet work environment needs of a healthy, positive, friendly, and respectful work environment through organizational and employee health and well-being programs and through employee assistance program.

These six HR service objectives can be used to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of specific HR programs, and to develop three HR strategic objectives: building HR capacity, building HR performance, and building HR community.

Building HR capacity is accomplished through the first two HR service objectives of staffing and employee development and relates to the first two parts of the WPF—human resources and enablers, the subjects of Chapters 2 and 3, respectively.

Building HR performance is accomplished through the third HR service objective pertaining to performance management and relates predominantly to the middle three parts of the WPF—inputs, processes, and outputs, the subjects of Chapters 4, 5, and 6, respectively.

Building HR community is accomplished through the last three HR service objectives that pertain to diversity, fairness, legal compliance, employee rewards and benefits, and the work environment. These topics relate to the last two parts of the WPF—outcomes and impacts, the subjects of Chapters 7 and 8, respectively.

The WPF makes the necessary connection between organizational goals and the human resources within the organization. The following chapters explain how the HR manager can use the WPF to align HR strategic objectives, HR service objectives, and HR programs to develop measurements for evaluating program efficiency and effectiveness. These insights should prove highly valuable for meeting the HR challenges of the 21st century.