Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Advanced Consulting

Earning Trust at the Highest Level

Bill Pasmore (Author) | Jeff Hoyt (Narrated by)

Publication date: 03/20/2020

Advanced consulting requires both expertise and personal qualifications that are distinct from those needed in everyday consulting. Advanced consultants work with high-level executive teams on complex issues such as strategy, organizational design, merger integration, digital disruption, culture change, and system-wide transformation. While neophyte consultants are often given a playbook to follow, advanced consultants need to invent methods that take full advantage of the opportunities that their work with clients presents.

There is an art to advanced consulting as well as a science; who you are is as important as what you do. Bill Pasmore draws on his four decades of experience as a consultant and teacher of consultants to show readers how to see possibilities that are not evident, conduct analyses that support the value of more comprehensive work, build relationships that engender deeper trust, adapt to changing circumstances, and empower members of their team to take independent actions while maintaining overall control of an engagement. Illustrated with vivid real-world examples and including a self-assessment to measure your progress, this book equips you to advance to more senior positions in your firm or to build a successful independent practice.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Advanced consulting requires both expertise and personal qualifications that are distinct from those needed in everyday consulting. Advanced consultants work with high-level executive teams on complex issues such as strategy, organizational design, merger integration, digital disruption, culture change, and system-wide transformation. While neophyte consultants are often given a playbook to follow, advanced consultants need to invent methods that take full advantage of the opportunities that their work with clients presents.

There is an art to advanced consulting as well as a science; who you are is as important as what you do. Bill Pasmore draws on his four decades of experience as a consultant and teacher of consultants to show readers how to see possibilities that are not evident, conduct analyses that support the value of more comprehensive work, build relationships that engender deeper trust, adapt to changing circumstances, and empower members of their team to take independent actions while maintaining overall control of an engagement. Illustrated with vivid real-world examples and including a self-assessment to measure your progress, this book equips you to advance to more senior positions in your firm or to build a successful independent practice.

—Vinita Gupta, CEO, Lupin

“If you've ever wondered what it takes to consult at the highest levels of an organization, this book will help you peek behind the curtain and see that there is indeed a method that underlies the magic. Based on Bill Pasmore's own journey from academia to advanced consulting, this book provides a firsthand account of what it takes to truly win the trust of senior executives—and take your career to the next level of impact.”

—Ron Ashkenas, Emeritus Partner, Schaffer Consulting, and coauthor of the Harvard Business Review Leader's Handbook

“Dr. Pasmore has helped numerous CEOs successfully transform their organizations and has also defined the field of organizational leadership. All his work shares an overarching theme—the attention to both the ways to get things done and the people in the organization and in his own team. This book is a must-read not only for senior consultants but also for any change agents who want to influence their organizations.”

—Dr. Harvey Chen, Chairman of the Board of Advisors, Center for Creative Leadership, Greater China

“Advanced Consulting focuses on working with C-suite clients, but it is much more than that. It is the best book I have read on consulting since Block's Flawless Consulting, covering a wide range of topics from business to psychology. Each chapter provides simple, but not oversimplified, models that any consultant will find useful.”

—Gervase R. Bushe, Professor of Leadership and Organization Development, Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University; author of Clear Leadership and The Dynamics of Generative Change; and co-editor of Dialogic Organization Development

“Having been a senior consultant and now on the client side, it's clear to me how valuable it would be for consultants who wish to hone their craft and become senior partners to read this book. It's a shortcut to gaining vital knowledge that would require years of experience to obtain.”

—Juan Carlos Rivero, Chief Talent Officer, Marsh & McLennan Companies

ONE

What Is Advanced Consulting?

Advanced consulting involves working with powerful, high-level parties such as CEOs, boards, or senior teams on strategic, confidential, complex, systemic, or high-risk problems or opportunities. The terms expert, trusted advisor, or senior partner are often used to describe the consultant guiding this kind of work. In this book, the focus is on advanced organizational consulting although advanced consultants in other fields should find much of value here.

Because a great deal is at stake, advanced consultants need to establish credibility with clients in order to engender the trust needed to win engagements. This credibility is derived from two sources: deep expertise in the subject at hand and personal qualities that inspire confidence. Neither of these things is easily gained. Experience is vital but experience alone is insufficient, unless that experience produces learning that deepens expertise and strengthens personal qualities. To become an advanced consultant, you can’t simply do more of the same; you need to deepen your knowledge while seeking feedback that allows you to grow as an individual. Even in large, successful consulting firms, only a few senior partners are capable of winning and guiding the most advanced work. They are the ones who invested in expanding their capabilities, building their networks, and searching their souls to discover what they need to do and who they need to be. If you would like to be one of them, don’t underestimate the work involved.

What kind of work does advanced organizational consulting entail? Our minds immediately go to the multi-year, multimillion dollar large-scale transformation projects, and these certainly qualify as advanced consulting. However, these large assignments are rarely won unless the consultant is able to work at a number of levels simultaneously. Advanced consulting work can be categorized into four clusters: (1) trans-organizational projects that involve things such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A), joint ventures, partnerships, supply chain design, shaping regulatory requirements, or community engagement efforts; (2) systemic organization-wide projects involving things like culture change, organization design, digital disruption, implementing new strategies or business models, installing new enterprise systems or processes, lean manufacturing, agile innovation, start-up/scaling, talent planning, or employee engagement; (3) work with senior teams or boards involving team composition, alignment, team effectiveness, accountability, role clarification, decision making, team development, board effectiveness, committee structures, and charters, and (4) individual coaching and advising of CEOs, chairmen, lead directors, or senior leaders on their effectiveness, relationships, talent choices, succession planning, priorities, learning, networks, organizational initiatives, key decisions, response to crises, executive compensation, and personal well-being.

What You Need to Know

To do any of this work, you’ll need to be prepared. You’ll have to understand the challenges and opportunities that accompany work at this level. Naturally, you must be able to demonstrate expertise in the domain in question, whether it be M&A, organization design, or understanding the role of board committees. You’ll also need to know how to help clients take full advantage of the opportunities that present themselves in the moment while overcoming the challenges. You must be able to undertake a comprehensive yet efficient diagnosis that pulls disparate data into a coherent, cogent, and persuasive call to action, leading to appropriate next steps.

FIGURE 1.1 Four Kinds of Advanced Consulting Engagements

Advanced consulting requires both expertise and personal qualifications that are distinct from those needed in everyday consulting.

Underlying the movement from collecting data to formulating a plan of action is foundational knowledge in a number of disciplines, including psychology, social psychology, organization psychology, organization development, systems thinking, organization theory/design, strategy, governance, leadership, and more. Yes, you can learn to consult using methods you have been taught or interventions you read about in a book—but without foundational knowledge, you won’t know why you are doing what you are doing or what to do when things go wrong.

What You Need to Do

To formulate effective change strategies, you must grasp what makes work at this level and this scale different: what the concerns of the key players are, how politics among the parties could affect decision making, why stakeholders might throw a wrench into the works, what the parties are not telling you, and how to use your informal authority to shape key decisions. Moreover, you’ll need to be able to engage your clients in dialogue and establish trust, credibility, and a willingness to collaborate in formulating solutions. There is an art to this work as well as a science. Some experienced consultants would tell you that the relationship they develop with their clients is more important than the actual work itself. I prefer to think it’s both, not one or the other. Nevertheless, I agree that advanced consulting is more personal than distant. Even though the work is strategic, the involvement of both the client and the consultant is deeper emotionally. This is in part due to the fact that it really is lonely at the top, meaning that senior leaders have very few people they can speak to openly and vulnerably. It’s also due to the fact that the work is hugely consequential in that it can and does affect the lives of many others in ways that are sometimes good and sometimes not. With great power comes great responsibility. To treat this kind of advising as if it’s only a job is as wrong as robbing a bank.

To treat this kind of work as if it’s only a job is as wrong as robbing a bank.

Who You Need to Be

All of this means that, in advanced consulting, who you are is as important as what you know. Your personal brand is a combination of your individual reputation; your network of contacts; books or articles you have written; and whatever weight is given to the imprimatur of your firm, if you belong to one. But even all that doesn’t guarantee that you can walk in the door and start working; how you handle yourself in the moment counts as much or more as anything else. Studies in social psychology have demonstrated that people begin formulating judgments about others within milliseconds of meeting them. We can be fairly certain that the same applies to consulting relationships, especially when the context raises the level of intensity and anxiety for the parties involved. Therefore, success in advanced consulting depends on who you are as well as what you do.

In the chapters that follow, I’ll address what you need to know about the work, how to develop your personal brand, and the art of advanced consulting.

Needless to say, the journey requires commitment. How quickly you get there is up to you. Although there is a lot to learn, you don’t have to wait until you have gray hair to do advanced consulting. There’s a lot to be said for youthful enthusiasm and unbounded optimism. However, long-term success requires more than making a good first impression. You’ll be tested; that’s when what’s beneath the surface matters.

There is an art to advanced consulting as well as a science; who you are is as important as what you do.

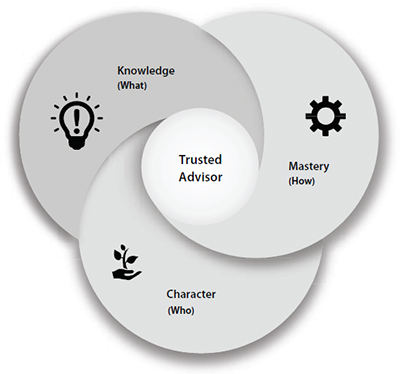

Earning Trust at the Highest Level

Becoming an advanced consultant involves learning what you need to know, mastering how the work is done, and being the person you need to be (see Figure 1.2). Many people are experts on a particular topic. Expertise is necessary but not sufficient to succeed in consulting to those at the highest levels. Without it, you will be denied entry. With it, you have the table stakes to get in the game but not necessarily to win. Knowing what to do with your knowledge is equally as important. Mastering the art of designing effective actions that produce critically important changes in performance is what is required to meet client needs. If you can’t help your client win, you don’t win. Finally, you need to be the right person for the job. The idea of “fit” with your client is important here, so there isn’t a single answer to who you must be to succeed at advanced consulting. However, there are things about you that over the long term will make you more successful than others who lack those traits. Among them are energy, passion for the work, the ability to form relationships, empathy, openness, honesty, humility, and putting the client’s interests first.

FIGURE 1.2 Earning Trust at the Highest Level

The combination of your character, the knowledge you can access, and your mastery of the work is what inspires trust, which is the key to continued success in advanced consulting. Welcome to the world of earning trust at the highest level.

Contrast: Beginner versus Advanced Consultant

Here’s a real scenario. The CEO/owner of a multinational conglomerate reaches out to you through one of her staff members with a request to provide some help regarding issues within her senior team. They are planning to spend a few days away together, reviewing strategies and making important decisions about investments, divestitures, joint ventures, and potential acquisitions. Part of the agenda will be devoted to improving the effectiveness of the team. The key challenge the team is facing is described as people working in silos and relating to the CEO individually rather than working together as a team with the best interests of the whole company in mind.

Advanced consultants see opportunities differently than less-experienced consultants do; they investigate multiple hypotheses to figure out what’s really going on.

A less-experienced consultant might accept the assignment without further inquiry because they have done team building previously using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and know it to be a reliable conversation starter. The consultant’s belief is that by using the MBTI, team members will be able to explain their typical interaction patterns and see why their differences in personality might cause tensions or misunderstandings. Knowing these things, they will be able to construe conflict in the team as a difference in the way people think rather than the result of fundamental differences in goals or beliefs. With less conflict, the willingness of team members to collaborate should increase.

The experienced consultant would approach the situation differently. Before selecting a tool, the advanced consultant would begin thinking about what might be causing tensions among members of the team. While differences in personalities could be playing a part, these differences might simply be exacerbating deeper issues. Some (but not all) of the hypotheses that could be explored would include the following:

• Team members are in competition for investments in their businesses; they see the world through a win-lose, fixed-pie perspective, in which they must convince the CEO to favor their business over others. In the process, they cast doubt on other team members in their individual conversations with the CEO, which leads to mistrust and dissention among the team members.

• Some team members have closer relationships with the CEO than others. Resentment among team members grows as they jockey for the CEO’s favor.

• Since there is no obvious successor for the CEO, each member of the team is vying to be considered as a candidate to become the next CEO. People who do not like the front-runners do their best to undermine them.

• Some businesses face greater competitive threats than others; this makes them possible targets for divestiture. Turning these units around would require considerable resources, which would mean that fewer resources would be available to help other lines of business grow. The leaders of the threatened units feel they have no choice but to fight for their survival.

• The CEO actually wants the tension in the team to continue because it maintains her importance as the savior of the organization since she is the only one who can settle disputes.

• There are hidden interpersonal issues that are a result of things that people have done to harm the reputation of others in the past. Because these things are never discussed, they remain smoldering and ready to erupt at any moment.

• The design of reward systems reinforces competition rather than collaboration among team members.

• Interpersonal issues are intertwined with sexism and racism that are undiscussable.

• Several team members have made plans privately to depart the organization if they don’t “win”; they feel they have nothing to lose by trying to “take others out.”

• Some people have developed allies within the team who agree to work against the interests of certain businesses or people.

• Some members of the team are negotiating potentially attractive partnerships with external entities that would increase their political capital; since they would be vital to the prospective partnership, they would be less likely to be removed from the team and so have less incentive to collaborate with others.

• The team has not developed because it has never gone through the storming that would lead to agreements about how the team should operate. People fear the confrontation and keep it submerged.

• There are fundamental disagreements about the goals the organization should pursue. While there is a broad strategy in place, each person interprets it differently. This leads to disagreements about each person’s role as well as disputes about processes for decision making, which causes more interpersonal conflict.

The advanced consultant wouldn’t accept the assignment without first learning more about what’s going on and certainly wouldn’t see the MBTI as a complete remedy for the team’s lack of collaboration. After conducting a thorough diagnosis, the advanced consultant would be in a better position to recommend a course of action to the CEO and set appropriate expectations for what might be accomplished through the upcoming meeting. Understanding that there may not be sufficient psychological safety to address the issues, the advanced consultant first asks the team to answer the question, “Why should we want to work more closely together?” before trying to force them to do so.

Formulating hypotheses and developing a truly effective plan of action should be based on an understanding of what motivates individuals, how individual behavior is affected by the context in which it occurs, the politics of senior teams, theories of team development, experiences in working with teams in similar situations, a command of intervention choices, systems thinking, and how meaning is socially constructed in ambiguous circumstances.

To convince the CEO that more is going on than can be remedied by a simple exercise or short discussion, the advanced consultant will need to leverage his or her experience, reputation, expertise, and ability to develop a trusted relationship with the CEO.

Note that the work of the inexperienced consultant could be met with praise by the team because it was fun and interesting, and that it might satisfy the CEO because the CEO would like to think that a simple and quick exercise can solve the problems the team is facing. Being an advanced consultant doesn’t mean that clients automatically see the value in your perspective or like your approach. The challenge is to help your clients see what you see and understand why simplistic solutions won’t address deeper or more systemic issues. Sometimes, it may simply be too scary or demanding for some clients to do what needs to be done—at least for the moment. But what is the alternative? Should advanced consultants recommend solutions they know will be ineffective? Or should they be patient, support clients in doing what they can manage at the time, but remain firm in continuing to engage them in doing what needs to be done?

Each opportunity is either one that can be minimized or one that can lead to significant breakthroughs. Being an advanced consultant opens up the choice.

The challenge is to help your client see what you see.

Learning How to Do Advanced Consulting

In your hands is a book that attempts to explain the finer points of advanced consulting. Hopefully, you’ll find the knowledge offered here helpful on your learning journey, as you would a French-English dictionary in preparation for a trip to Paris. But as with a French-English dictionary, reading this book doesn’t mean that you will be an effective advanced consultant, any more than reading the dictionary will help you to speak perfect French. There’s a difference between possessing bits and pieces of knowledge and being an expert in a given profession.

The Part You Can Learn from Reading a Book

Let’s be clear about what you can learn from reading this book. You will come to understand what advanced consulting is and the topics it addresses. You will acquire a map of what you need to learn and a synopsis of the curriculum you should follow. You will hear stories that are intended to convey a tactile sense of the work itself. You will be handed a mirror to use in examining your qualifications as well as the fit between your personal character and the demands of the work. You’ll know some vocabulary, the tenses, how to conjugate verbs, and the rules of grammar. Yet you won’t know how to speak the language until you engage in conversation.

Like learning a new language, your attempts to engage in dialogue will feel awkward at first. You’ll make mistakes, you’ll be corrected, and sometimes you will find yourself very, very lost or terribly frustrated. Not knowing the art of advanced consulting may cost you an assignment or even two or three. You may land work that ends prematurely or, even worse, in a request from the client to your firm that you not be invited to the next meeting.

If you aren’t prepared to make mistakes while learning in public, you’ve chosen the wrong profession.

Learning a new language isn’t easy; no one gets it right the first time. If you aren’t prepared to practice in public and weather the consequences of making mistakes while learning, you aren’t cut out for this line of work. You won’t get to where you need to go by playing it safe.

The Part That Requires Getting Your Hands Dirty

What you learn by “getting out there” is that your best guesses aren’t good enough, your reading of the client is off base, what worked previously doesn’t apply, and that you’re spending too much time worrying instead of paying attention. There are no perfect opening lines, no foolproof interventions, and no way to get every client to like you. In the face of your inability to control the situation, you do a couple of things to survive. First, you learn from your experience so that you’re more prepared the next time; and second, you learn to get better at adapting in the moment. Instead of relying on a routine, you develop a repertoire.

Instead of relying on a routine, you develop a repertoire.

Early in your consulting career, you quickly find yourself in over your head. You can’t possibly know everything about everything—every topic, every industry, and every client motivation. Because you feel you are not meeting expectations, you do things you shouldn’t do: pretend you know more than you do, insist on an approach that was successful in the past but isn’t a good fit for the current situation, or take a random shot in the dark. These are not valid learning attempts; even if they succeed, they provide no clues to what you need to do to be successful in the future. If you need to learn in order to get better, the first thing you need to admit, at least to yourself, is your ignorance. Only then can you begin a legitimate search for the knowledge you need to proceed with confidence.

To get better, you have to admit your ignorance—at least to yourself.

How do you learn what you need to know? There are basically two choices. You go it alone, reading everything you can, quizzing colleagues for ideas, and continuing to experiment until you have some idea of what works and what doesn’t. Or you can apprentice yourself to an experienced practitioner who is willing to let you “ride along” as they ply their craft. You can do both, of course, and that’s the optimal strategy for learning as quickly as possible. For either or both strategies to succeed, you will need to make some good choices about what to learn and who to learn from.

You might consider acquiring an advanced degree, which, as its descriptor suggests, is designed to teach you things you need to know to become an advanced consultant. The structure of the program will help you avoid taking a “random walk through the park,” which would be likely if you set out on your own. Just be careful that the program is designed by people who have actually practiced advanced consulting. While purely academic programs can provide foundational knowledge, the real payoff is in understanding how to apply that knowledge to advanced consulting situations. To understand how to actually do the work, you should consider combining formal studies with observing a master at work.

The Apprentice Model

Deciding whether to apprentice and with whom may be the most important decision of your career. Apprenticeship is so important to learning the finer arts of a profession that in the Middle Ages in Europe, there was simply no other route to becoming a master craftsman. Today, we see the strong influence of the apprentice system in how doctors are trained as well as in such diverse professions as the theater, aircraft piloting, and the building trades. An apprenticeship is especially important to learning skills that are more easily taught through demonstration than purely cognitive methods.

As a young pilot in training, I had read books and articles about flying. I knew that taking off was rather simple: you lined the plane up with the far end of the runway, advanced the throttle, waited until the plane accumulated enough speed to fly and then gently pulled back on the stick or control wheel. The tricky part was learning to land. Because you begin the landing process in the air rather than on the ground, you need to be able to judge the effects of the wind on the track of the plane over the ground; you can’t simply line up the plane with the end of the runway. Then, you need to begin a descent by reducing power just enough for the plane to gradually lose altitude without going too slowly, which would cause the airplane to stall, resulting in a crash that would probably be fatal because it occurred too close to the ground to recover. You need to learn to control the descent by balancing the amount of power supplied by the engine with the angle of the nose of the aircraft—if the nose is too high, the aircraft will go slower as it attempts to climb without sufficient power until it reaches the point of a stall. Lowering the nose (pointing it at the ground) causes the plane to lose altitude too quickly unless the power is reduced. All of this has to happen while determining whether you have enough, but not too much, altitude to reach the near end of the runway; if not, power will need to be added and altitude maintained before starting to descend again. As you steer the aircraft over the runway threshold at an angle that will allow the plane to roll down the runway once you land, you need to find a perfect combination of the nose pointing up slightly and the aircraft descending minutely with the power completely off to minimize the forward speed and therefore the length of the ground roll. At the same time, you are paying attention to any side drift created by crosswinds and making small directional adjustments to keep the airplane headed down the runway. You eventually land by pulling back on the stick or wheel very gradually but still quickly enough to reduce the forward speed and land near the close end of the runway, with the wheels touching down so gently that you aren’t sure exactly when you stopped flying. If you are lucky.

While what you just read is factually correct, I dare any non-pilot to jump into an aircraft and try it without first receiving instruction (not that it would be legal to do so). In the early days of aviation, there were no instructors. The Wright Brothers were lucky; they crashed but survived. Many of their peers and predecessors did not. The risks of non-instructed landings are consequential.

Watching my instructor demonstrate how to land the airplane many times over helped me understand the visual and audible clues that influence a pilot’s judgment concerning the track of the airplane over the ground, the power supplied by the engine, and the angle of the nose of the plane. Keeping these things in proper balance is an art, not a formula. In a dual-control-wheel aircraft like the one in which I learned, I progressed from pure observer to placing my hands lightly on the controls, following the subtle movements my instructor made without him having to think about them consciously. Having to think about them would make the response to conditions too slow; the pilot would always be “behind” the airplane, trying to correct for conditions that no longer existed. Instead, the pilot needs to learn to anticipate what will happen next as small changes are made through the controls based on the sensory inputs received.

This is why if you’re worried about whether you are doing the right thing as a consultant, you will never keep up with your client. You will always be behind, out of step with the client’s reactions to your last micro-intervention. The best way to learn to keep up is to observe someone who really knows what they are doing without having to think about it.

Observing a master consultant at work illuminates what good practice looks like, but it does not explain how he or she is processing information and making split-second decisions. Understanding what’s behind the choices made requires dialogue. The apprentice needs to interrogate the master and the master needs to offer insights into his or her stream of consciousness. Some of the choices are purely instinctive; others are calculated to produce a particular effect. Over time, as more client interactions are observed, a pattern begins to emerge through the post-meeting dialogues that reveals more about how the master uses knowledge, pays attention to cues, and maintains a focus on where the work needs to go. Understanding the pattern is like understanding what jazz musicians are attending to as music is co-created or what a boxer reads in his opponent’s eyes. It’s the finer points that differentiate between the greats and everyone else.

The apprentice model offers other benefits as well. The more experienced consultant can provide opportunities that sustain the apprentice until the apprentice can win assignments unassisted. The master has a network that is much larger and more valuable than that of the apprentice, simply by virtue of their longer and more varied career. The master can use the network to open doors, make introductions, or provide leads to expertise in specific domains. The reputation of the master can carry over to the apprentice, providing a permanent “seal of approval” that can be referenced again and again. Within large consultancies, the support of a senior partner can ease the route to partner for an associate.

Finding a mentor offers multiple benefits.

When difficulties arise, as they always do, few people can empathize as well as one’s mentor. For all these reasons, I highly recommend that you make a point of developing a relationship with someone who can guide you. Those who go it alone make the journey much more difficult and longer than it needs to be; but more importantly, they miss out on relationships that can be meaningful to both parties.

I was fortunate to have several mentors over the course of my career. I learned from all of them. I wish I had spent even more time observing them and asking questions. I had a sense of their importance but never a plan to take full advantage of the gifts they were offering. It wasn’t always easy. There were times when things didn’t go well, times when I made mistakes or failed to deliver what was expected. I could have reduced the negatives had I shared more of my thinking before deciding on my own what needed to be done. I underestimated their willingness to mentor me and the benefits they derived from doing so. I chose instead not to bother them when it wouldn’t have been a bother at all. I’ve also learned that there is such a thing as reverse-mentoring and have enjoyed learning about technology, other cultures, and domain-specific expertise from younger colleagues. The journey does not end.

Planning Your Personal Journey

Presuming you still have a long runway ahead of you, give some thought to planning your journey to become an advanced consultant. As you read this book, make notes in the margin or online about things you need to learn. When you pause to reflect, go back to these notes and plan how you will learn what you need to know. Is it reading an article or a book? A degree program? A short course? A podcast or webinar? Or is it a committed apprenticeship, and, if so, with whom? As with all learning, two things will increase your chances of success. One is prioritizing your goals and committing them to paper; the other is sharing them with someone who will hold you accountable. That someone could be your mentor and for your sake, I hope it is. Malcolm Knowles (Knowles 1975), the learning theorist, has demonstrated that committing your plan to paper increases the chances that you will implement it. Committing it to paper and sharing it with someone who can act as an accountability partner does even more. If you care about your future, trust in Malcom’s advice.

Self-Assessment

In the Resources section at the end of the book is a self-assessment tool provided for your personal use. It covers important ground: the elements of advanced consulting and your honest appraisal of the skills you will need to learn or improve to realize your vision. If you pause to take it now, you will prepare yourself with a “baseline” measurement that can guide your learning journey. I strongly suggest that if you are interested in learning to be an advanced consultant, you take the assessment. It will help you pay attention to what you need to learn as you read, as well as what you need to do to gain the experience you will need to succeed.

I would also encourage you to take it again after you have finished reading the book. It’s likely that some of your priorities will change once you learn more about the elements of advanced consulting.