Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Battling Healthcare Burnout

Learning to Love the Job You Have, While Creating the Job You Love

Thom Mayer MD (Author) | Thom Mayer, Md (Author) | Dave Clark (Narrated by)

Publication date: 06/29/2021

Burnout is among the most critical topics in healthcare as it deprives us of our most important resource—the talents and passion of those who perform the difficult work of caring for patients and their families. The purpose of this book is to provide not only a taxonomy of burnout within the landscape of healthcare but also to provide pathways for healthcare professionals to guide themselves and their organizations toward changing the culture and systems of their organization.

The work of battling burnout begins from within. Thom Mayer views every healthcare team member as both a leader and performance athlete, engaged in a cycle of performance, training, and recovery. In these roles, they must both lead and protect themselves and their teams.

Battling Healthcare Burnout looks at individuals' role in promoting change within themselves and their organization and addresses solutions to change the culture and systems of work. Both are presented with a pragmatic focusand a liberal use of examples and case studies, including those from several nationally recognized healthcare systems.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Burnout is among the most critical topics in healthcare as it deprives us of our most important resource—the talents and passion of those who perform the difficult work of caring for patients and their families. The purpose of this book is to provide not only a taxonomy of burnout within the landscape of healthcare but also to provide pathways for healthcare professionals to guide themselves and their organizations toward changing the culture and systems of their organization.

The work of battling burnout begins from within. Thom Mayer views every healthcare team member as both a leader and performance athlete, engaged in a cycle of performance, training, and recovery. In these roles, they must both lead and protect themselves and their teams.

Battling Healthcare Burnout looks at individuals' role in promoting change within themselves and their organization and addresses solutions to change the culture and systems of work. Both are presented with a pragmatic focusand a liberal use of examples and case studies, including those from several nationally recognized healthcare systems.

1

Why Burnout Matters

Knowing what we know gives us peace. But knowing what we don’t know gives us wisdom.

CONFUCIUS1

The Way We’re Working Isn’t Working

What if half of the physicians, nurses, and healthcare team members providing care to you and your family were burned out? How confident would you be that a team with half its members suffering from burnout would deliver optimal quality of care? That prospect is today’s unsettling reality. Burnout has reached epidemic proportions, affecting up to 60 percent of physicians and 50 percent of nurses, depending on specialty.2–6 The costs of burnout to organizations and providers are devastating, with negative effects on employee turnover, patient safety, quality, productivity, and personal health.7 The challenge of dealing with the coronavirus pandemic did not create the epidemic of burnout, but it did accentuate it, as well as the necessity for actionable solutions.8

Simply stated, the way we’re working isn’t working. How could it be working when half of our team members suffer burnout and the consequences are so high? Our only hope is to exert inspired leadership to change these realities. The definition of burnout will be discussed in more detail later, but it can be succinctly stated:

Burnout is a mismatch between job stressors and the adaptive capacity or resiliency required to deal with those stressors, which results in three cardinal symptoms:

1. Emotional exhaustion

2. Cynicism

3. Loss of a sense of meaning in work9

In addition to this definition, this book relies on three additional insights:

1. Every member of the healthcare team is a leader who needs leadership skills to

• lead yourself, lead your team

• lead their team

2. Every member of the healthcare team is a performance athlete engaged in a cycle of performance, training, and recovery.

• Invest in yourself.

• Invest in your team.

3. The work begins within. Start with what you can control: you.

(As Marcus Aurelius noted, if you want good in the world, you must first find it in yourself.) Finally, as Bryan Sexton, a professor at Duke, points out, at a personal level, burnout results in a diminished ability to experience the restorative effects of positive emotions, as if a veil stood between us and our passion.10

Why does burnout matter? Is it simply an annoyance, or is it a deep problem infecting our ability to deliver quality patient care by committed, passionate clinicians and the team supporting them? How common is the problem, and what differences are there among our team members? How and why does it happen? How does it affect patients, those caring for patients, and the broader healthcare system? This chapter summarizes what is currently known regarding these questions, with the intent of helping guide solutions. It also lists what we don’t know.

Burnout matters for five reasons:

1. Burnout is human suffering among our healthcare teammates, blunting our ability to feel positive emotions.

2. Burnout is common, affecting up to 50 percent of physicians and nurses.

3. Burnout is expensive, costing the healthcare system $4.6 billion per year.11

4. Every measure by which we monitor progress in healthcare gets worse with burnout.

5. There is no “meter” or “gauge” on our foreheads indicating, “Danger—this person is burned out.”

Leadership is essential to preventing and treating burnout—lead yourself, lead your team.

Prevalence of Burnout in Healthcare

The prevalence of clinician burnout has been studied extensively, with most of the work with physicians and nurses. The simplest answer to “Who burns out?” is “Everyone, to varying degrees.” Let’s examine the data.

PHYSICIANS

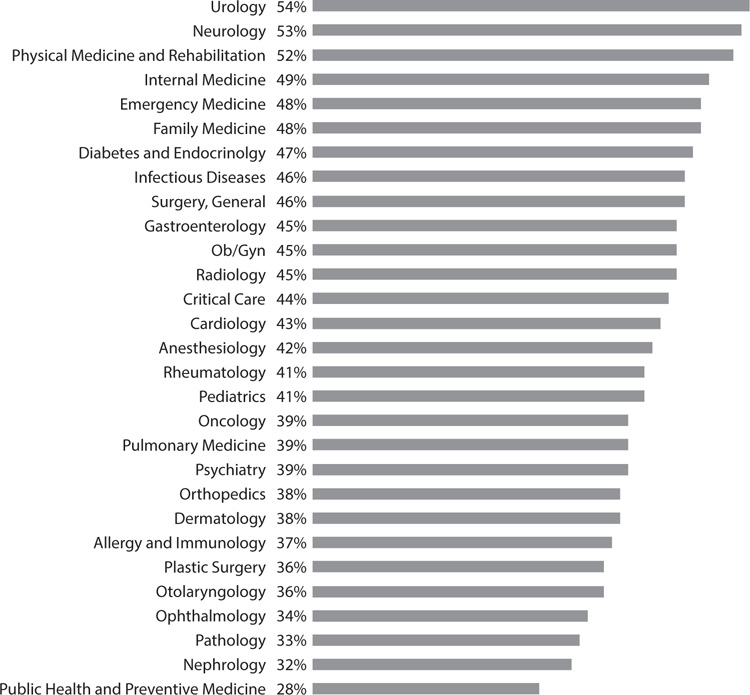

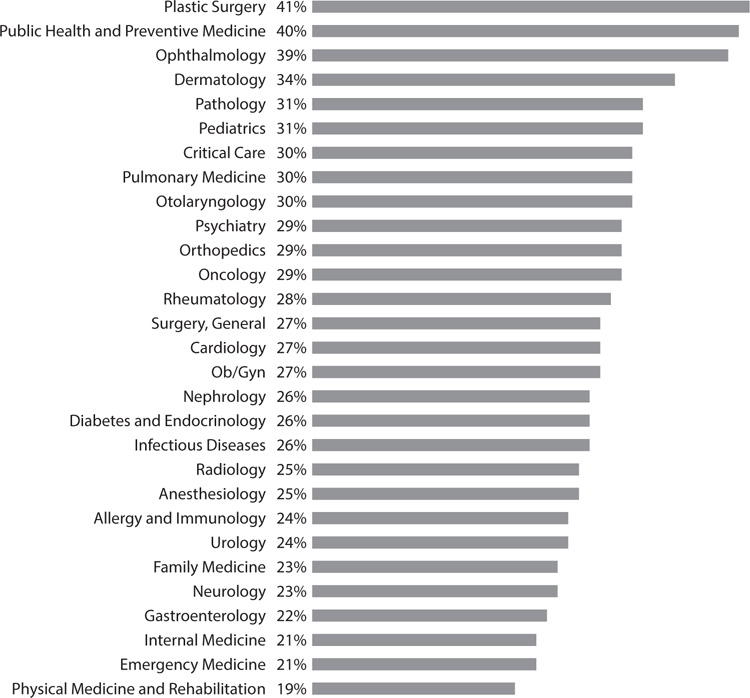

Current data indicate that a minimum of 40–55 percent of physicians have experienced significant symptoms of burnout, with higher rates among physicians on the front lines of medicine who have extensive direct patient care responsibilities, including those in emergency medicine, family medicine, general internal medicine, critical care medicine, and neurology (Figure 1-1).12–14 Conversely, those physicians who rated themselves as the happiest are largely those off the front lines of medicine and in specialties in which patient care is more elective in nature (Figure 1-2).15 James Reason cites Shakespeare’s Henry V, “We are but warriors for the working day,” and then states that emergency physicians and nurses “stand on the front line between the hospital (the rear echelons) and the hostile world of injury, infections, acute illness. The nature and extent of these enemies are not really known until the moment of the encounter. And the encounter itself is brief, singular, hugely critical, largely unplanned and full of surprises and uncertainties. These skirmishes offer an almost unlimited number of opportunities for going wrong.”16

Figure 1-1: Burnout Rates among Physician Specialties13

Figure 1-2: Physician Self-Ratings of Happiness at Work13

Viewed from this perspective, it is not surprising that we sometimes get it wrong on the front lines of medicine, but what is surprising is that we so often get it right.17 Given the type and volume of stressors to which physicians and nurses are constantly exposed, it isn’t surprising that nearly half of them have burned out—but it is surprising that figure isn’t even higher.

Burnout is nearly twice as common in physicians when compared with other US workers after controlling for other factors, including work hours.18 Recent data reiterate that this is the case, even though physicians have been shown to have higher resiliency,19 accentuating the magnitude of the problem. It is alarming that burnout is occurring at younger ages, with a high prevalence among medical students and residents compared with people of a similar age pursuing other careers.20

This is undoubtedly due in part to the fact that medical students, residents, and recent residency graduates have more concerns regarding work-life balance and related issues than in previous generations. Chuck Stokes, one of the most trusted voices in healthcare leadership, argues that the younger generation of clinicians will have to “constantly reinvent themselves” over the course of their careers, evolving their areas of interest and their span of practice to avoid burnout and sustain their passion.21

While all of these prevalence rates will undoubtedly change over time—and hopefully some of the strategies designed to prevent and treat burnout will be effective—it is safe to say that no less than 35 percent and as much as 50 percent of physicians have substantial symptoms of burnout. It is a staggering insight when you consider that every other doctor may be burned out, particularly when the costs of burnout are considered, from decreased quality of care to effects on patient safety, even before financial costs are calculated.22–24

NURSES

Linda Aiken and her colleagues at Penn did the earliest and most extensive work on nurse burnout rates, which have typically been reported to be between 35 and 40 percent.25–26 They noted in a 2002 study of over 10,000 inpatient nurses that 43 percent reported a high degree of emotional exhaustion.27 (Most of the work done on nurse burnout has focused on the emotional exhaustion aspect of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which arguably may skew the picture when comparisons are made to physician burnout data. For this and other reasons, further work is needed on nurse burnout, its sources, and solutions.) Some of the work on nurse burnout, particularly in the emergency department, focuses on the concept of “compassion fatigue,” a close variant or cousin on the burnout spectrum, typically described as an erosion of the capacity to show empathy or compassion.28

The relationship between specialty area and burnout in nurses is less extensively studied, but there are some data that suggest higher rates in hospitals than in other settings and that nurses in high-stress settings such as ICUs and oncology units may have higher burnout rates, which, if borne out, may dictate targeted therapies for those groups.29

ESSENTIAL SERVICES: OTHER HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS

As a theology major in college, I was taught that all language has meaning and all behavior has meaning. One of the more disturbing things concerning the language of healthcare is how we refer to the members of the healthcare team other than nurses and doctors—those in the laboratory, radiology, finance/registration, environmental services, and others. In virtually every hospital and healthcare system in the nation, they are referred to as ancillary services. The word ancillary comes from the Latin word ancilla, the precise translation of which is “female slave.”30 Webster’s definition is only slightly less demeaning when it comes to those with whom we work in healthcare: “subordinate, subsidiary.”31 The more accurate term is essential services, since we could not operate any area of healthcare without these teammates. Stop allowing our team members to be called “ancillary”—they are essential to our work and should be recognized and treated accordingly.32

Much less is known about the prevalence of burnout symptoms among our essential services team, including physician assistants,33 nurse practitioners,34 dentists, pharmacists, hospital support staff, and healthcare leaders/administrators. Research is under way in all these areas to quantify prevalence rates, including an ambitious effort by Mayer, Shanafelt, Trockel, and Athey to study burnout among members of the American College of Healthcare Executives.35 While precise rates are not known, there is every reason to believe that the mismatch of job stressors and adaptive capacity that produces burnout is no less common in these team members, so solutions to prevent and treat burnout should be developed for them as well.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN BURNOUT

Without question, the challenges facing women physicians are different from those faced by males, including a lack of role models; a lack of parity in compensation; a lower number of promotions to leadership positions; specific challenges of childbearing, child-rearing, and dual-career couples; higher rates of sexual biases and harassment; and a limited window of childbearing years. While gender alone is not yet a consistent predictor of burnout, some studies indicate that, after adjusting for personal and professional factors, women are at increased risk for burnout, perhaps by as much as 30 to 60 percent.36–38 In 2017, a study of 15,000 physicians from 29 specialties found that burnout was self-reported by 48 percent of female physicians versus 38 percent in their male colleagues.37 Whether this is due to a higher prevalence, the assessment tool itself, or a higher likelihood of women to report symptoms is currently unknown, but all should be subjects for further study.

Limited but intriguing studies indicate that there are subtly important differences in the ways that burnout is manifested, with women showing higher levels of emotional exhaustion and men with higher scores in cynicism/ depersonalization.39–40 Being a parent lowers the risk of burnout, which may be accounted for in many ways, including having higher adaptive capacity to deal with stressors.41

RACIAL DISPARITIES IN BURNOUT

Do people of color experience burnout differently or at different rates? Answers to these questions are of critical importance, and studies are only now being undertaken to find them. Initial reports are perhaps counterintuitive in that they show that physicians in minority racial or ethnic groups have considerably lower rates of burnout than their White counterparts.42 In addition, favorable reports of work-life balance among Black physicians are perhaps due to better family support.43 This is an issue that will be the subject of further study, as will whether there are differences in the symptoms of burnout and the resiliency of these physicians.

The racial disparity gap in healthcare outcomes is well documented and transcends income, geography, and social status. Alarmingly, the Football Players Health Study at Harvard, which is the “Framingham Study” of former NFL players funded by the NFL Players Association, shows dramatic gaps between White and non-White football players’ health outcomes (including psychological maladies), even accounting for education and income.44 Whether this proves true in physicians of color remains to be seen. During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals of color contracted the virus at a rate 50 percent higher than their White colleagues, and studies are under way to understand the long-term effects.45 How this affects burnout is the subject of ongoing research.

The Cost of Burnout

While there are clear financial costs from burnout, it is always critical to remember that the highest cost is the suffering it causes to the people on our teams. The human side of burnout is stark, raw, and all too real. Burnout’s propensity to prevent us from enjoying the pleasures derived from caring for patients by blocking the ability to fully enjoy the positive emotions arising from clinical practice is a huge tragedy.

But there are also financial costs, and making the case for preventing and treating burnout will always have a fiscal dimension. At a time when healthcare reimbursement is declining, each healthcare expenditure undergoes scrutiny to determine its value and return on investment (ROI).46–49 An exegesis of the costs of burnout makes the case for its effective recognition, prevention, and treatment, particularly when the costs to the individual, the team, the organization, and society are all considered.47–49 The interrelatedness of these elements is shown in Figure 1-3. Burnout matters in all these areas, but they are deeply connected when it comes to calculating the cost of burnout and its total impact. Keep this in mind:

Every measure of progress in quality in healthcare—however you define quality—gets worse with burnout.

Figure 1-3: The Costs of Burnout

THE COST OF BURNOUT: THE INDIVIDUAL

The costs of burnout to the individuals suffering from it are undeniable, persuasive, and devasting in their scope and effect. They include this haunting list:

• increased risk of cardiovascular disease50

• hypercholesterolemia51

• musculoskeletal pain55

• prolonged fatigue56

• gastrointestinal disorders57

• respiratory illnesses57

• motor vehicle injuries

• suicide58

• alcohol excess63

• drug use64

• residents—higher risk of needle sticks, bodily fluid exposures58

• occupational health issues

This litany is sad and unsustainable, and immediate action is needed to stem the tide of suffering for physicians. Burnout has a negative impact on nearly every aspect of an individual’s physical, mental, psychological, and emotional health. The personal toll is apparent from these comments from my interviews with clinicians:

As burnout set in and worsened, it seemed that whatever was “wrong” in my life got worse.

It’s just a downward spiral—things don’t seem to get better.

It’s crazy—I’m a doctor, but my “numbers” on my blood tests just got worse and worse as the burnout symptoms got worse, even when I changed my diet and exercised more.

I’m not doing anything I tell my patients to do when it comes to health—how pathetic is that?

I can’t eat, I can’t sleep, I can’t even seem to smile anymore at work. That’s not why I became a doctor.

I realized that if I was seeing in my patients what I was seeing in myself, I would tell them, “You can’t keep doing this! This is horrible for your health at every level!”

As these quotes illustrate, burnout represents real suffering among people dedicated to preventing and relieving the suffering of others. Healthcare leaders have a duty to create cultures of passion and hardwire flow and fulfillment in their systems and processes to eliminate or reduce that suffering. Since we don’t have a “burnout meter” embedded on our foreheads, we have to develop ways by which to measure our teams’ status.

THE COST OF BURNOUT: THE TEAM

For teams as for the individual, the work begins within. The fundamental importance of teamwork is that it makes the job easier and is thus a source of intrinsic motivation. Nietzsche wisely said, “He who has a strong enough ‘Why’ can bear almost any ‘how.’”65 Teamwork helps us understand the “why” before the “how.” Leadership and teamwork are two sides of the same coin—the ability to make the job easier. I will address the broader costs of the effect of burnout on the organization and society writ large later, but there is also undoubtedly a serious cost to the teams providing healthcare, over and above that seen at the macro level. Chapters 8–10 will address the importance of teamwork solutions to burnout. Ineffective teamwork leads to a higher, more complex workload, poor communication, a sense of unfairness, and a lack of clear values—all elements of the six domains of burnout defined by Maslach and Leiter and discussed in Chapter 3.

Teams are not just groups of people who work together to produce defined results—teams are groups of people who trust each other. The culture, systems, and personal passion disconnect that produce burnout fundamentally result in an erosion of trust, exemplified by a lack of effective teamwork.

If I can’t trust my teammates to take care of themselves, how can I trust them to take care of others?

Battling healthcare burnout requires innovation, and innovation can only occur at the speed of trust, since team members who cannot trust one another can’t innovate. Prospective, nonrandomized studies indicate that turnover of any team member increases the likelihood of turnover of other team members within 12 months of the turnover, even when that team member is replaced.66 All of this speaks to the contagious nature of burnout, which is attested to by the practical experience of leaders at all levels of healthcare. The cost to the team isn’t just turnover—it is the insidious nature of the effects of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of personal accomplishment on the ability of the entire team to work as a high-performing group and its erosion of personal and team spirit.

The cost of burnout to the team also matters because team-based care has been shown to improve outcomes in each of the areas shown in the following list, which span a broad range of patients.66–70

• hypertension

• diabetes mellitus

• cancer

• geriatric care

• primary care clinics

• pediatrics

• emergency department

• joint replacement

• behavioral health care

• disaster medicine

• air medical care

• sports medicine

THE COST OF BURNOUT: THE ORGANIZATION

There are multiple costs to healthcare organizations and healthcare systems of burnout, each of which must be considered. This cost analysis is often important to justify the time and expense of the burnout and resilience initiative.

The Business Case for Burnout When considering the “business case for burnout,” it is common to use the term return on investment. When considering the business of execution in healthcare, it is always both necessary and appropriate to consider not only whether something new actually works but also whether it can be afforded in today’s capacity-constrained healthcare environment. It should also be asked, of all the things in which we could invest, why is preventing and treating burnout something in which we should invest? In the post-COVID-19 era, where the disease created tremendous stressors on the front lines of healthcare, Victor Dzau and his colleagues have argued persuasively for the prevention of a “parallel pandemic” of burnout threatening our workforce.71 The business case for burnout shows that the ROI is dramatic, but also demonstrates that, in making the case, we move to a nonintuitive yet unavoidable answer.

Question: How can we afford to address burnout?

Answer: You can’t afford not to address burnout!

Given the data supporting the costs of burnout at every level, healthcare leaders not only have a moral and ethical responsibility to address burnout, they also have financial and fiduciary responsibilities to do so. Let’s look at the data that support this, which concern each of the following areas:

• turnover

• patient revenue and productivity

• quality

• safety: medical errors and malpractice risk

• patient experience

• absenteeism, presenteeism, and worker compensation issues

• branding and reputational costs

Turnover Nowhere are the burnout data clearer than in the direct connection between burnout and physician and nurse turnover within two years of its identification. Reports from Stanford, the Cleveland Clinic, the Mayo Clinic, and University of California–San Francisco show that physicians with burnout are twice as likely to leave their institutions.72–75 Turnover of A-team members, both physicians and nurses, is devastating to any healthcare organization at every level. To lose the best of the team to burnout is even more concerning since in most cases it should be preventable or treatable. The connection between burnout and turnover is unquestioned. The odds that a physician intends to leave a job increase 200 percent with burnout. For each 1-point increase in emotional exhaustion on the Maslach Burnout Inventory or 1-point decrease in job satisfaction, there was a 28 percent and 67 percent higher level of work reduction effort and loss of productivity, respectively.75

John Brennan and his colleagues at Wellstar Health System in Atlanta have shown that the actual cost to the organization of the turnover of one physician exceeds $500,000 and is likely closer to $1,000,000.76 Atrius Health reports the cost to replace a physician at $1,000,000 to $500,000.77 Other studies indicate that it costs two to three times a physician’s annual salary to replace that physician.78 The cost of turnover among RNs has been estimated to be 1.2–1.5 times their annual salary.79

Patient Revenue and Productivity The loss of productivity at the national level has been estimated to be the equivalent of annually eliminating the classes of seven medical schools.4 Without question, burnout is associated with decreased productivity in nurses and physicians, and it may also cause lost revenue, particularly in surgical specialties, during the time it takes to replace physicians.

Quality Several studies describe a link between the decline in quality indicators, including core measures, postdischarge recovery times, test ordering, prescribing habits, and patient adherence to medication recommendations.80–83 Studies of both residents and attending physicians show that burnout is a predictor of failing to answer patients’ questions and discussing treatment options with them. Nurse burnout negatively affects supervisor ratings of nursing performance.84 The emotional exhaustion score among nurses increases the likelihood that patients will rate the hospital negatively, will not recommend the hospital, and will perceive their communications with nurses negatively.84 Nurse burnout rates correlate with nurse ratings of the hospital’s safety culture,85–86 surgical site and catheter-associated infections,87 and overall care quality.86

Safety: Medical Errors and Malpractice Risk The link between burnout and medical errors has been shown in multiple studies, including one demonstrating an 11 percent increase in medical error rates, poor communications between providers and patients, and increases in patient safety incidents.80 In a study of 7,100 US surgeons, controlling for other personal and professional factors, burnout was tied to reporting a major medical error, as well as being involved in a medical malpractice suit. Major medical errors were also increased among internal medicine residents with burnout. Mean burnout levels in nurses were associated with higher rates of healthcare-associated infections. Perhaps most concerning are the data showing a direct link between burnout and malpractice claims.82–83 Given all these data, who would want to be taken care of by a burned-out healthcare team?

Patient Experience The correlation between patient experience scores and burnout is intriguing. In environments where the numbers of patients seen per clinician per day are not subject to intense scrutiny, physicians with higher patient experience scores burn out at significantly lower rates. This includes emergency physicians and specialists in hospital medicine. (To be clear, both of these specialties have metrics to hardwire flow as a part of their practices, but they are not mandated to spend only a certain amount of time with their patients.)

However, among internists and family medicine practitioners, where the pressure to see more patients per day drives stressors, physicians with higher patient satisfaction scores have higher burnout rates. This is probably due to the increased pressure to see more patients and a change in their habit of spending more time with their patients. One of the most common and strongest causes of burnout among this group is the pressure to limit the time they spend with patients in the drive to see more patients per day.

I’ll delineate this in detail in Chapter 8, but a key means to reduce burnout is to use evidence-based strategies to maximize the benefit of the time available with the patient. Simply stated, “It’s not just how much time you spend with the patient—it’s how you spend the time.”48

Using time wisely by following scripts as evidence-based and survey-based language is a powerful way to maximize patient experience in a time-constrained environment.

Absenteeism, Presenteeism, and Worker Compensation Issues Unsurprisingly, the triad of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of efficacy often leads to physical and psychological illnesses that keep burned-out physicians and nurses from working. Absenteeism from work has a cascade effect, since either teams must work short (with less than a full complement) or someone from a call schedule has to work. When the call schedule is used too often, that has a further demoralizing impact of increased work hours and even resentment toward those who are absent. Presenteeism refers to team members working while ill and therefore at a reduced productivity level. However, working while burned out has an even deeper effect, given the psychological impact a negative team member has on the rest of the team. Absenteeism and presenteeism have been shown to dramatically increase in the presence of high burnout rates, as have worker compensation claims.83–88

Branding and Reputational Costs Building and sustaining a positive brand and a positive reputation in the community, region, and even nation has become an important focus for hospitals and healthcare systems.89 Given the clearly demonstrated effects of burnout on negative aspects, outcomes, and ratings of care, it is nearly impossible to have a positive brand and reputation with a team whose burnout rates are excessive. Burnout and brand are thus on a collision course that is unsustainable over time, driving the realization that healthcare leaders cannot afford not to invest in programs designed to address burnout, including those that seek to change the culture, hardwire flow and fulfillment, and develop personal resilience and passion reconnect.

Calculating the ROI of Burnout Solutions At a time when healthcare reimbursement is under substantial scrutiny and terms like mitigation, reductions in force, furloughs, and doing more with less are rampant, all healthcare leaders must look at the investment of dollars and resources carefully, with the ROI lens front and center. However, the great news is that, given all the foregoing information, the math to calculate the effect of burnout interventions is not that difficult. The factors considered are the following:

• number of physicians or nurses

• turnover rate without burnout

• turnover rate with burnout

• cost of turnover per physician or nurse

• cost of the intervention

All of these data points are ones that should be tracked routinely in the burnout era and can be used to determine the effect of specific interventions. Here are the data needed in a sample calculation for a healthcare system with 500 physicians.

ROI Data Points for the Calculation

Net Return on Investment = Return on Investment – Cost of the Investment

N = number of physicians in the organization

x = Turnover (TO) rate from HR data

y = Current yearly burnout (B/O) rate from survey data

z = TO rate in physicians with burnout = 2 × those without B/O (from national benchmark data)

Cost of Burnout = N × x × $500,000 (from conservative national benchmarks)

For an organization with 500 physicians and a turnover rate of 10 percent, turnover of physicians is 50 per year, with a cost of burnout of $25 million:

N = 500

x = 10%

Total Turnover = 50 × $500,000 = $25 million

The 10 percent burnout rate can be broken down between “normal” turnover and that from burnout, with national benchmarks indicating that the rate is twice as high in burned-out physicians, represented by z.

10% turnover = 50% non-B/O physicians (A) + 50% B/O physicians (2A)

10% turnover = 3A

Turnover from non-B/O + A = 3.3%, or 17 of the total 50 physicians

Turnover from B/O = 2A = 6.7%, or 33 of the total 50 physicians

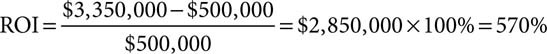

If the cost of intervention to prevent burnout of $500,000 results in a 20 percent reduction in burnout (from 50 percent to 40 percent), then the reduction in physician turnover of 20 percent relative risk would be 20 percent of 33 physicians, or 6.7 physicians per year, with a reduction in turnover cost of $3,350,000 (6.7 physicians × $500,000 cost of turnover per physician). The ROI calculation is as follows:

Any good chief financial officer would tell you that is an investment worth making for any healthcare institution. You can plug your own numbers in to do an ROI calculation for an investment in burnout.

Tait Shanafelt and his colleagues have developed two worksheets, one to project the organizational costs of burnout and a second to determine the ROI of an intervention.81 The following is a burnout assessment tool, the questions of which are a framework to assess an organization’s efforts in investing in burnout recognition, prevention, and treatment.

Burnout Assessment Tool

• Are you investing (ROI) in preventing burnout and increasing resiliency or adaptive capacity?

• How specifically are you doing that?

• Is it working?

• How do you know it’s working?

• What other investments should you make?

• What should you stop doing?

THE COST OF BURNOUT: SOCIETAL

Han and his team estimated that the societal cost of turnover and decreased productivity secondary to physician burnout may exceed $4 billion annually.4 Add medical errors, threats to patient safety, malpractice risks, decreased quality of care, turnover, and so on, and the societal investment in the education, training, and development of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals, which comes at least at some level from public funding, has its dividends seriously eroded by the scourge of burnout. All told, the societal, business, team, organizational, and personal toll of burnout among our team members must be addressed.

Implications for Solutions

With up to 50 percent of physicians and 40 percent of nurses experiencing symptoms of burnout, healthcare organizations simply cannot afford not to act in the face of this crisis. The good news is that two meta-analyses and systematic reviews show that organizational interventions can demonstrably reduce burnout, with even modest investments resulting in positive changes.54, 88 What is most clear from these studies is that both organizational and personal strategies must be undertaken to fully address burnout recognition, prevention, and treatment.

PHYSICIANS

• broad, general strategies for all physicians

• targeted solutions for physicians by group—for example, emergency medicine, family medicine, internists, surgeons, and so on

• programs to reduce stressors and increase adaptive capacity

• teamwork skills with nurses

• specific strategies for women physicians (including leadership, gender bias, sexual harassment, peer communities, and mentorship training)

• changes to the structure of medical schools, residencies, and fellowship training to reduce burnout

NURSES

• discrete programs for nurses at highest risk (emergency department, critical care, oncology, newborn intensive care unit, pediatric intensive care unit)

• development of programs to combat “compassion fatigue” in nurses

• development and implantation of team-based skills and communications across boundaries

Patient Burnout

While our discussion has focused on the people providing care and the burnout they experience, a similarly grave problem exists but has not been discussed: patient burnout. Simply stated, the same systems, processes, and cultures that create burnout in healthcare professionals have also created a mismatch of adaptive capacity or resilience and the stressors of being a patient, which create exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of accomplishment—patient burnout. Patients have never been more frustrated with healthcare systems than they are currently, as multiple studies attest. At a time when mantras like “Patient first” and “Patient always” are proudly proclaimed, listening to the “voice of the patient” tells us that we have made access to care difficult, do not transmit information effectively or efficiently or in a way patients can understand, and even “torture” them by making it difficult for them to find a place to park to get to us. They often arrive in our treatment areas more anxious and frustrated than when they started and become even more so when they see a nicely framed expression of a mission, vision, and values that proclaims how dedicated we are to our patients—even as we have forced them through a gauntlet of obstacles to access to care.89–90

Patient burnout is subject to the same domains as provider burnout. As patients seek to navigate their way toward health, there is definitely a mismatch between the stressors in their healthcare journey and the adaptive capacity needed. Without question, they feel a loss of control. Far too often, there is a loss of a sense of reward and recognition, even when they are fully compliant and show improvement in key healthcare metrics. Ask your patients and they will often tell you that our healthcare system lacks a sense of fairness. Finally, when a sign proclaims the importance of the patient, but the patient waits hours, days, or weeks for access to care, the values are called into question.

While this patient is grateful for her medical care, the very process by which she receives it puts her at greater risk for a fall in navigating that care, as well as frustrating her tremendously. The culture and the systems and processes by which care is delivered seem to have been designed specifically to ignore the patient’s needs and desires. I could provide thousands of similar cases in which patients are burned out with our healthcare system. As one patient told me, “Doc, if you call this a healthcare system, I think you need to look up the definition of those words. Isn’t the patient the only reason you guys exist?”91

CASE STUDY

Maureen Vance is a 55-year-old female with a history of osteoporosis and hip, back, and extremity fractures. Her treatment requires an injectable synthetic parathyroid hormone to stimulate bone growth. The injections are given not by a physician but by a nurse practitioner. The healthcare system that provides her care has a main campus and multiple satellite facilities, one of which is 5 miles from her home. The main campus is 25 miles from her home, is undergoing construction, and is almost impossible to access easily. While valet parking is provided, the line to drop off a vehicle is over 30 minutes long and even longer when the vehicle is picked up, because of extremely limited parking and an understaffed, harried valet service.

Once the car is parked, it takes a 20-minute walk and three different elevators to get to the office. Once there, despite arriving 15 minutes early, she waits an hour to be put in a room, where she waits 25 more minutes. Once the nurse practitioner arrives, she hurriedly gives the injection, which takes less than 2 minutes, then leaves. Mrs. Vance waits 20 more minutes for a nurse to “discharge” her, which consists of having her sign some papers and giving her 10 dense pages of discharge instructions, which are not discussed with her. When she asks why the injection could not be given at the satellite facility near her home, she is told, “That’s not our policy.”

Recognizing that patients can burn out just as members of our team can should drive efforts to constantly change our systems to hardwire flow and value into every process through the eyes of the patient.

Once this concept of patient burnout is understood and the elements of it are recognized, it is time to move to a therapeutic alliance between the patients and their families and the care teams responsible for them. That starts with “making the patient a part of the team.”90–91

MAKING THE PATIENT A PART OF THE TEAM

The concepts of teams and teamwork are essential to success in hospitals and healthcare systems, as I’ll discuss in detail in Chapters 8–10. A team is not a group of people working together; it is a group of people who trust each other. I believe that the single most common problem in healthcare is failing to make the patient a part of the team. Shouldn’t all healthcare teams make the patient not just a member of the team but the most important member of the team?

That statement, accusatory as it may unintentionally seem, requires exegesis. It starts with an understanding of the voice of the patient, which is distinct from, if related to, the provider’s understanding of and empathy with the patient; both of the latter are important, but neither actually captures the voice of the patient.

Capturing the voice of the patient starts with moving from one question—“What’s the matter with you?”—to another, deeper one: “What matters to you?” This is not verbal acrobatics, but rather a shift in focus from pathology to the patient’s needs. Doing so starts the journey of transforming the patient from being a recipient of care to becoming a participant in their care.91

One additional part of making the patient part of the team comes from a British colleague who noted that the motto for patient-centered care should be “Nothing about me without me.”92

PRECISION AND PERSONALIZED PATIENT CARE: A BURNOUT SOLUTION

Ralph Snyderman and Sandy Williams at Duke University School of Medicine first described the concept of precision and personalized medicine,93 wherein the treatment of illnesses and injuries is specifically tailored to the unique needs of the individual patient, not just generically developed and implemented. Precision medicine begins with asking this simple question of every patient, every time: “What can we do for you to make this an excellent healthcare experience?” Note the pronoun we, which indicates the team nature of patient care. The focus is on “you,” the patient, in an effort to discover what would be “excellent” (not just good or very good) today. I’ll unpack this in more detail in Chapter 8, on personal approaches to improving care and resilience.

Summary

• The most important cost of burnout is the human suffering it produces in our team, with exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of meaning at work.

• Every measure of quality and safety in healthcare gets dramatically worse with burnout—we can no longer afford the cost, which may be as high as $4.6 billion per year.

• The business case for addressing burnout is impressive and far-ranging, and should include a calculation of the return on investment (ROI).

• Specific solutions should be targeted to physicians (including by specialty), nurses (including critical care and emergency department nurses specifically), essential services team members, and so on to ease human suffering while reducing the cost of burnout.

• Just as healthcare team members burn out, patients burn out as well, compounding the problem.

• Making the patient part of the team and employing precision and personalized patient care are two strategies that should be a part of every solution.