Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Federal IT Capital Planning and Investment Control (with CD)

Thomas G. Kessler (Author) | Patricia A. Kelley (Author)

Publication date: 03/01/2008

Federal IT Capital Planning and Investment Control is the first book to provide a comprehensive look at the IT capital planning and investment control (CPIC) process. Written from a practitioner's perspective, this book covers a range of topics designed to provide both strategic and operational perspectives on IT CPIC. From planning to evaluation, this valuable resource helps managers and analysts at all levels realize the full benefits of the CPIC process.

Explore the full range of IT investment principles and practices

Learn CPIC project management techniques including earned-value management, integrated baseline review, cost-benefit analysis, and risk-adjusted cost and schedule estimates

Identify strategies to improve how your organization manages its IT portfolio and selects, controls, and evaluates investments

Discover how to leverage scarce IT resources and align investments with program priorities

Benefit from the in-depth coverage—excellent for the experienced as well as those new to the CPIC process

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Federal IT Capital Planning and Investment Control is the first book to provide a comprehensive look at the IT capital planning and investment control (CPIC) process. Written from a practitioner's perspective, this book covers a range of topics designed to provide both strategic and operational perspectives on IT CPIC. From planning to evaluation, this valuable resource helps managers and analysts at all levels realize the full benefits of the CPIC process.

Explore the full range of IT investment principles and practices

Learn CPIC project management techniques including earned-value management, integrated baseline review, cost-benefit analysis, and risk-adjusted cost and schedule estimates

Identify strategies to improve how your organization manages its IT portfolio and selects, controls, and evaluates investments

Discover how to leverage scarce IT resources and align investments with program priorities

Benefit from the in-depth coverage—excellent for the experienced as well as those new to the CPIC process

Thomas G. Kessler, DBA., CISA, has over 30 years of experience as a manager, strategic planner, and information systems specialist. He was a consultant to more than 30 federal agencies from 1996 to 2006. Prior to establishing his own consultancy, Dr. Kessler worked for the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Westinghouse Electric Corporation, and the Maryland State Judiciary. Dr. Kessler is co-author of The Business of Government: Strategy, Implementation, and Results, with Patricia A. Kelley. He is a frequent speaker at professional conferences.

Patricia A. Kelley, DPA, CISA, has over 25 years of strategic planning, program evaluation, and operational management experience. She has provided management consulting support to more than 30 federal agencies, and has held senior management positions with the Federal Reserve Board. Dr. Kelley has also worked extensively with the Federal Reserve Banks on automation and payment system policy matters, and has acted as the liaison to other federal banking regulators. Previously, Dr. Kelley evaluated the effectiveness of various federal programs for the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

CHAPTER 1

Overview of Capital Planning and Investment Control

Perfect order is the forerunner of perfect horror.

—CARLOS FUENTES, MEXICAN AUTHOR

After the Clinger-Cohen Act became law in 1996, its implementation progressed slowly. By the early 2000s, federal agencies were still struggling to implement IT investment management principles, largely because of resistance to changing long-standing approaches, power arrangements, and organizational culture. Substantial effort and resources were expended to implement CPIC processes to comply with Clinger-Cohen requirements, but many implementations were guided by two principles: (1) merely comply with OMB requirements and (2) do so in a way that does not interfere with “how we do business because we are very busy and our methods have worked fine for many years.”

The only practical way for an agency to maximize return on its IT investment is to treat its collective set of IT assets as a portfolio and to actively analyze, strategize, monitor, and manage the entire portfolio so that it achieves optimal performance.

By 2006, agencies were better positioned to meet Clinger-Cohen and OMB requirements for IT management reform, yet progress was still inconsistent and erratic. Today, most agencies have implemented CPIC processes and are now wrestling with the challenge of instituting change in their organizational cultures to realize the full potential of CPIC.

This chapter presents an overview of the CPIC process. It discusses CPIC goals, the roles and responsibilities of key participants in CPIC, the formal structure of CPIC, and the documentation necessary to support decision-making and monitoring. It also provides insight into the implications of the CPIC process for an agency and offers suggestions for improving existing CPIC processes, including a checklist for conducting a self-audit.

Maximizing Return on Investment

The only practical way for an agency to maximize return on its IT investment is to treat its collective set of IT assets as a portfolio and to actively analyze, strategize, monitor, and manage the entire portfolio so that it achieves optimal performance. The CPIC process provides the framework for doing so. It should be designed to achieve the following goals:

Ensure that IT use is aligned with the agency’s key performance goals and management initiatives

Ensure that IT use is aligned with the agency’s key performance goals and management initiatives

Monitor and control IT performance and prioritize the use of the agency’s resources so that the IT portfolio provides maximum return on investment

Monitor and control IT performance and prioritize the use of the agency’s resources so that the IT portfolio provides maximum return on investment

Maximize success when acquiring or developing new IT systems and control the costs of maintaining existing IT systems

Maximize success when acquiring or developing new IT systems and control the costs of maintaining existing IT systems

Provide for an impartial decision-making process that enables those involved in the CPIC process, subject to approval of the agency’s executive leadership, to make resource-allocation decisions based on an objective methodology

Provide for an impartial decision-making process that enables those involved in the CPIC process, subject to approval of the agency’s executive leadership, to make resource-allocation decisions based on an objective methodology

CPIC requires a formal structure and process that enable those who are involved at various times to move in and out of their CPIC roles and responsibilities based on the timing and needs of that involvement. The efficiency and effectiveness of an agency’s CPIC structure and process will determine, to a large extent, whether agencies are really maximizing return on investment or just going through the motions of OMB compliance and wasting valuable time and resources.

Although numerous approaches can be followed in designing the CPIC structure and process, we have characterized a general approach that can be customized to meet the unique needs and context of a particular agency. In adapting this approach, an agency should include the following elements:

Senior leadership must be actively involved, and programs must be represented.

Senior leadership must be actively involved, and programs must be represented.

Sufficient data collection and analytical resources must be available.

Sufficient data collection and analytical resources must be available.

There must be a single decision point for IT project approval and resource allocation decisions.

There must be a single decision point for IT project approval and resource allocation decisions.

CPIC must be integrated with other agency processes, including the budget, strategic planning, procurement, security, and project management.

CPIC must be integrated with other agency processes, including the budget, strategic planning, procurement, security, and project management.

The process must comply with the requirements of OMB Circulars A-130 and A-11.

The process must comply with the requirements of OMB Circulars A-130 and A-11.

The process should reflect the varying levels of importance of the agency’s investments; small investments should not require an unduly burdensome drain on the time and resources needed to manage the investment.

The process should reflect the varying levels of importance of the agency’s investments; small investments should not require an unduly burdensome drain on the time and resources needed to manage the investment.

CPIC should be as simple and efficient as possible, to minimize the burden on those who are involved part-time in the process.

CPIC should be as simple and efficient as possible, to minimize the burden on those who are involved part-time in the process.

Roles and Responsibilities

An effective CPIC process requires the support and involvement of key individuals throughout the organization. The Clinger-Cohen Act appropriately shifted strategic IT decision-making from the CIO to the executive leadership and programmatic leaders of the organization. As a result, executives, senior managers, and agency staff across the organization have specific roles to play in the CPIC process.

Agency Head

As with most major strategic initiatives, the agency head (in the case of cabinet-level departments, the secretary) sets the tone for how the process will be received throughout an agency. For CPIC to be more than a mere exercise in compliance, the agency head must champion the process through demonstrated actions such as:

Describing and supporting the CPIC process through formal policy announcements

Describing and supporting the CPIC process through formal policy announcements

Requiring that IT decisions be made through the CPIC process and ensuring proper linkage of CPIC to the budget

Requiring that IT decisions be made through the CPIC process and ensuring proper linkage of CPIC to the budget

Requiring formal reporting mechanisms for major IT initiatives

Requiring formal reporting mechanisms for major IT initiatives

Fostering creative uses of IT that further the agency’s mission and improve efficiency

Fostering creative uses of IT that further the agency’s mission and improve efficiency

Preventing “end runs” around the decision-making, control, and evaluation processes

Preventing “end runs” around the decision-making, control, and evaluation processes

In short, the agency head, while not needing to be involved in CPIC on a tactical basis, should be the catalyst for instituting and supporting IT management accountability and stewardship.

Assistant Secretaries

An agency head generally establishes broad policy goals and a vision of success for the agency. The assistant secretaries are then responsible for refining and implementing policies to achieve the vision. This same relationship exists for complying with Clinger-Cohen and implementing the vision of the agency head for maximizing return on IT investment. Successful CPIC requires that assistant secretaries be actively engaged in CPIC to position and deploy technology so that it supports mission achievement.

Assistant secretaries, generally working through subordinate senior managers, are able to communicate that the agency takes its IT investment management responsibilities seriously. Senior-level commitment is vital because assistant secretaries are best able to deal with the resistance, inertia, confusion, political gaming, and turf guarding that can derail an effective CPIC function. During the first two or three years of implementation, while the process is being institutionalized, secretary-level executives must actively oversee the establishment of the CPIC framework and the agency’s commitment to enforcing cultural change.

Senior Program Managers

Senior program managers play a critical role in the CPIC process on both a strategic and tactical level. They are responsible for making investment choices and monitoring the performance of existing investments. They are directly responsible and accountable for assets that support their respective programs, and they must be involved in providing sufficient oversight and management. It is the senior program managers who will be most affected by the CPIC process in terms of time commitment, decision-making responsibilities, pressure to compromise, and assignment and acceptance of accountability.

Chief Information Officer

The CIO is central to the CPIC process, playing important roles in its design and implementation, representing the agency to OMB, ensuring compliance, and providing advice to all participants, including the agency’s executive leadership. The CIO’s staff generally supports the decision-making and monitoring processes by collecting and analyzing data that are presented to senior management. The CIO also ensures that participants understand the risks and implications of their decisions.

In most agencies, the CIO is responsible for both IT policy and strategic direction and for overseeing system development and operations functions. For this reason, the CIO plays an additional key role in implementing CPIC practices at the project team level. This includes working to overcome any cultural resistance, promoting the importance and benefits of CPIC, and ensuring that project teams fully participate in and support CPIC activities.

Chief Financial Officer

The CFO typically has more expertise in investment management concepts and principles than others in the agency and is therefore more likely to be supportive than most other agency executives by serving as the principal steward of agency financial resources. The CFO’s staff of financial analysts can independently analyze and assess business cases and IT financial analyses and can be invaluable as active CPIC process participants. The best CPIC results are realized when the CFO and CIO work together to ensure that the process is used and that everyone actively participates.

Chief Acquisition Officer

The chief acquisition officer (CAO) plays a critical role during the planning and acquisition phases of the investment life cycle. With increased reliance on purchasing off-the-shelf systems and using contractors to support system development, use of the acquisition process to competitively select qualified vendors has become a key to investment performance and success. The CAO representatives develop market research and contracting strategies, and they provide leadership and support throughout the acquisition process.

The CAO is also responsible for ensuring that Clinger-Cohen acquisition reforms, such as incremental and modular contracting and performance-based acquisitions, are implemented. Contracting officers must be trained in and supportive of efforts to ensure that IT risk is equally distributed between the government and its IT contractors. The CAO staff should be responsible for reviewing and approving investment acquisition plans and should be active participants on integrated project teams.

End-Users/Customers

Although they are sometimes treated as an afterthought, the actual end-users, or customers, of an IT initiative must be involved throughout the CPIC process. End-users identify new uses of technology, provide feedback on the performance of IT investments, provide system requirements, approve system designs, and oversee implementation and subsequent operations and maintenance activities. They are also typically involved in preparing investment business cases and are important liaisons to CPIC oversight committees.

Agency Sponsor

Agency sponsors typically are executives or senior managers who need and want an IT system to support a particular program or activity. They are the primary IT system user. As such, they likely initiate the investment, include funds within their own program budget on an annual basis to pay its costs, and “contract” with the IT organization for development, maintenance, and operational support. In some cases an agency sponsor may consist of only a single program or organizational unit and in others there may be multiple programs or organizations that establish joint sponsorship. Sponsors, like champions, play a critical role in the CPIC process. Sponsoring organizations are the “buyers” of IT resources and beneficiaries of IT return on investment. As such, their CPIC role is to maximize their IT return on investment.

Investment Champion

While some agencies may not perceive a need to designate investment champions, those that have done so report that they are extremely satisfied with the results. The investment champion is typically someone from the sponsoring organization who understands and is enthusiastic about the investment. The champion is more effective if he or she is in a management position and/or has sufficient tenure and experience in the organization to know and deal with internal politics and processes.

The investment champion serves as the sponsor for a potential investment and often is the individual who came up with the idea or need for the IT project. The champion plays a critical role in creating enthusiasm for the investment and working with various groups to ensure that an effective business case is developed and that the project is accurately portrayed and explained as it proceeds through the review process.

Investment Manager

Historically, the primary technical manager associated with a system was the IT project manager. The project management role during major development is quite different from the role during ongoing operations and maintenance, and often the development project manager would discontinue his or her involvement with a project once it became operational. For example, the development project manager would typically develop a budget and project plan covering just the development phase of the investment. This created a sense of discontinuity in terms of leadership for an investment over its entire life cycle.

Because CPIC encompasses the entire investment life cycle, investments need managers that are different from traditional IT project managers, hence the introduction of an investment manager role. An investment manager is responsible for an investment over its entire life cycle. He or she may have several technical project managers reporting to him or her over time, but is responsible for preparing and justifying the investment budget throughout its various phases.

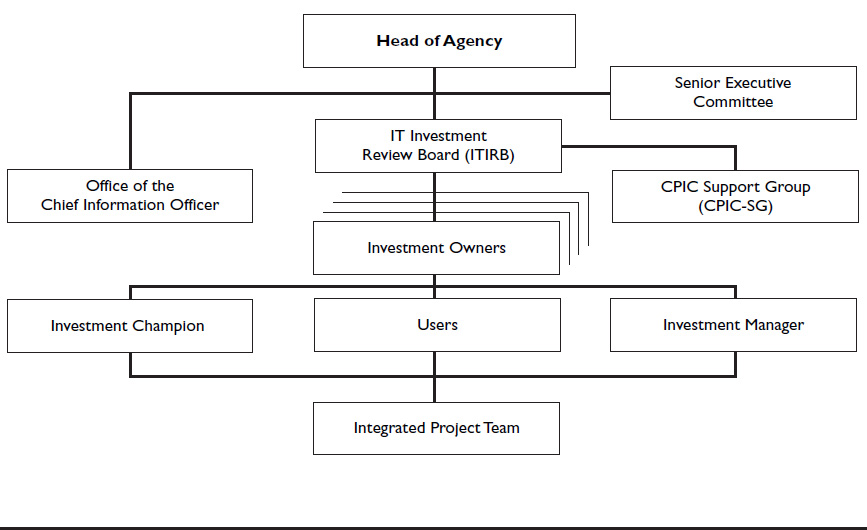

The CPIC Organizational Structure

Most agencies have an executive committee of some sort, composed of agency program leaders, often at the assistant secretary level, and chaired by the head of the agency. This executive committee is responsible for overseeing all policy, operational, and administrative functions. CPIC is most effective when it is tightly integrated with the executive committee. The executive committee should therefore establish an IT investment review board (ITIRB) as one of its standing committees and charter it to provide CPIC oversight. The ITIRB should brief and interact with the executive committee on a regular basis.

IT Investment Review Board

The ITIRB is the executive decision-making body for the CPIC process, setting goals and objectives for the agency’s IT portfolio and making decisions about the portfolio composition. While the CIO should always be an ITIRB voting member, an executive committee member other than the CIO should chair the ITIRB to demonstrate the agency’s commitment to user involvement and oversight of IT resources. The other ITIRB members can include executive committee members or their designees who will represent their interests. Figure 1-1 presents a generic CPIC organizational structure.

Figure 1-1  Typical CPIC Organizational Structure

Typical CPIC Organizational Structure

The ITIRB is chartered to:

Ensure that an agency-wide methodology is used to depict and assess agency performance, processes, information needs, and alignment of IT resources

Ensure that an agency-wide methodology is used to depict and assess agency performance, processes, information needs, and alignment of IT resources

Review material on the status and performance of the agency’s IT portfolio

Review material on the status and performance of the agency’s IT portfolio

Approve investment and funding decisions based on presentation of proposed actions to sustain and improve portfolio performance

Approve investment and funding decisions based on presentation of proposed actions to sustain and improve portfolio performance

Monitor the progress of IT investments and take corrective action if they encounter problems such as falling behind schedule, exceeding budget, or not achieving expected levels of functionality

Monitor the progress of IT investments and take corrective action if they encounter problems such as falling behind schedule, exceeding budget, or not achieving expected levels of functionality

For the ITIRB to make sound decisions, its members must receive sufficient and reliable information in the form of briefing packages. Because ITIRB members hold senior positions and have many other duties, a support team is necessary to coordinate the preparation of this information. For the purposes of this discussion, this group will be referred to as the CPIC support group (CPIC-SG). The CPIC-SG is typically managed by a CIO representative and staffed by full-time employees, part-time appointees from various functions through the agency, or a combination of the two.

CPIC Support Group

The CPIC-SG has a critical role in the CPIC process. It coordinates the agency’s CPIC process, collects and prepares all information for review by the ITIRB, and implements ITIRB decisions. In a sense, the CPIC-SG serves as the ITIRB gatekeeper. It typically leads the development of the agency enterprise architecture and portfolio analysis and coordinates a large number of groups and individuals to develop proposed changes to the agency IT portfolio. The CPIC-SG presents the status and performance of the agency portfolio to the ITIRB as well as proposals for changes to the portfolio, with associated analysis and justification. The CPIC-SG schedules and coordinates all ITIRB meetings and, at the request of the ITIRB, coordinates the preparation of other information needed by the ITIRB.

Integrated Project Team

As noted earlier, groups from various functions throughout the agency are likely to interact with the CPIC process at various times and for various reasons. Many participants will engage in ITIRB meetings, enterprise architecture revisions, portfolio analysis, or various other types of reviews and activities. Some will participate at the investment level, fulfilling a role as a member of an IPT.

An IPT usually includes a diverse group of individuals with complementary backgrounds who are assigned roles and responsibilities for managing, overseeing, and supporting a particular investment. The investment manager typically chairs the IPT, and the investment sponsor is often an active IPT member as well. Representatives from the IT organization play an essential role in IPTs because of their involvement in developing, maintaining, and operating the asset. Other key IPT participants include acquisition, security and privacy, and enterprise architecture specialists, as well as any others who can contribute specialized knowledge and expertise.

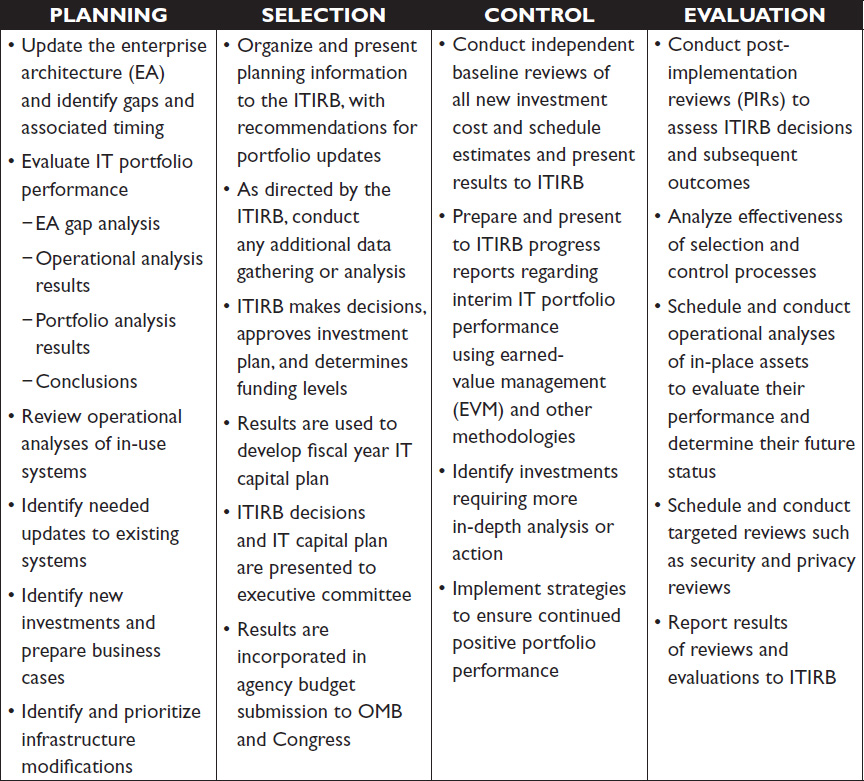

Phases of the CPIC Process

The CPIC process is designed to meet the key goals described earlier in this chapter. It consists of data collection, analysis, presentation, deliberation, and decision-making activities that occur throughout the year. A typical CPIC process is composed of the four phases described in Table 1-1, phases that overlap and interconnect.

Table 1-1  Phases of the CPIC Process

Phases of the CPIC Process

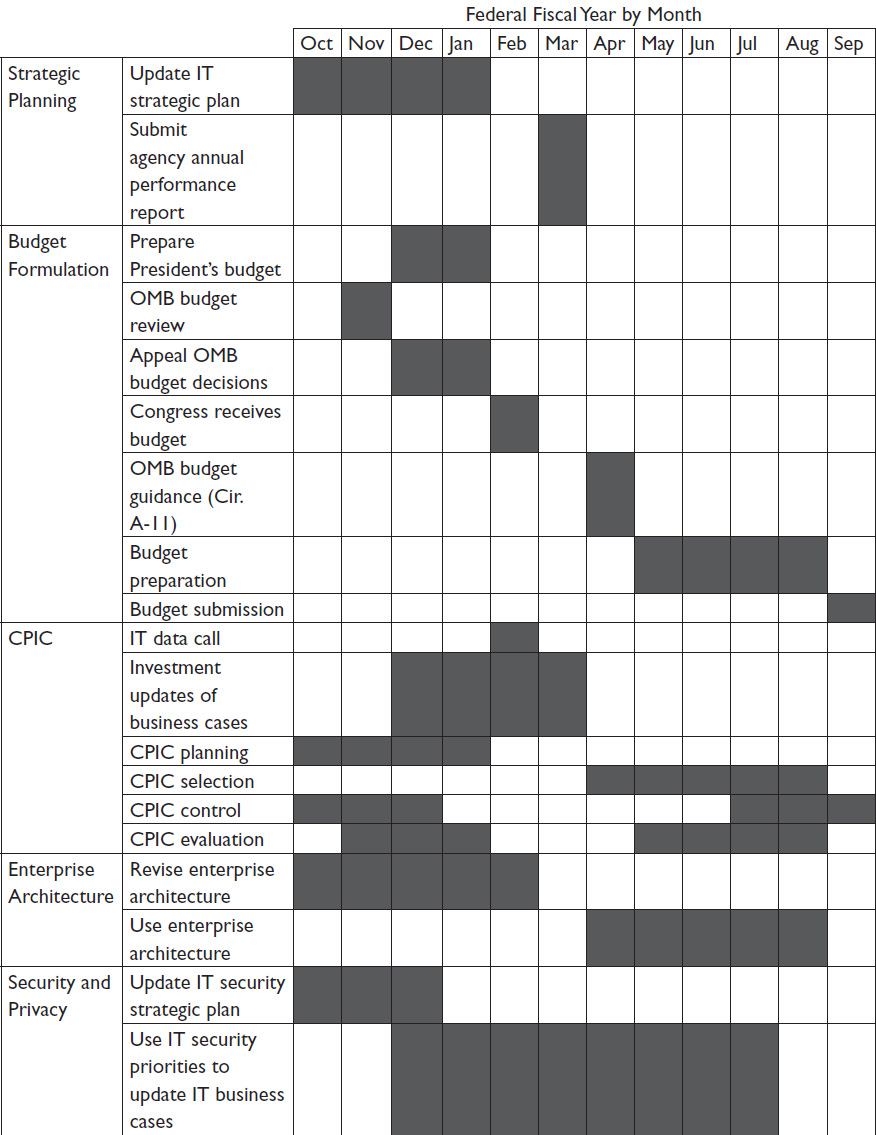

CPIC is a continuous process, with critical decision-making and monitoring taking place throughout the year. Timing of the four phases is closely aligned with the federal budget cycle. Table 1-2 presents a general overview of the timing of strategic planning activities, the agency budget cycle, CPIC timeframes, and the timing for updating and using enterprise architecture and IT security information.

Table 1-2  Federal Budget and IT CPIC Timeline

Federal Budget and IT CPIC Timeline

Planning activities take place before budget decisions are made to provide input to the budget decision-making process. The IT budget is developed during the selection phase as the ITIRB makes investment decisions. This phase precedes or proceeds in parallel with formulation of the agency budget. ITIRB decisions determine the IT funding requirements that are submitted to OMB for inclusion in the President’s budget.i Because planning and selection activities are labor-intensive, control and evaluation activities generally receive less attention while the budget is being formulated and more attention after it is submitted to OMB.

Planning Phase

Planning precedes the CPIC selection phase and consists of the preparatory analysis that is necessary to approve portfolio changes and additions in subsequent phases. During this phase, the CPIC-SG is responsible for ensuring that the agency enterprise architecture is reviewed and updated, and for conducting a review of the agency IT portfolio and associated investments.

According to the May 19, 2004, testimony of Randolph C. Hite, then Director of Information Technology Architecture and Systems Issues at the Government Accountability Office (GAO), “enterprise architecture” is defined as follows:1

In simplest terms, an enterprise is any purposeful activity and an architecture is the structural description of an activity. Building on this, we can view enterprise architectures as systematically derived and captured structural descriptions—in useful models, diagrams, and narrative—of the mode of operation for a given enterprise, which can be either a single organization or a functional or mission area that transcends more than one organizational boundary (e.g., financial management, homeland security).

The architecture can also be viewed as a blueprint that links an enterprise’s strategic plan to the programs and supporting systems that it intends to implement to accomplish the mission goals and objectives laid out in the strategic plan. As such, the architecture describes the enterprise’s operations in both logical terms (such as interrelated business processes and business rules, information needs and flows, and work locations and users) and technical terms (such as hardware, software, data, communications, and security attributes and performance standards). Moreover, it provides these perspectives both for the enterprise’s current (or “as-is”) environment and for its targeted future (or “to-be”) environment, as well as for the transition plan for moving from the “as-is” to the “to-be” environment.

Specific details for conducting enterprise architecture reviews are presented in subsequent chapters.

The objective of the planning phase is to comprehensively evaluate the present state and desired future state of the agency. The process involves documenting the outcomes that the agency is trying to achieve and carefully analyzing the agency’s organizational structure, strategies, and processes. Planning also entails forecasting how these factors are likely to change and the role that IT should play in the future. Developing a “to-be” vision for the agency and for IT assets and resources is a critical part of strategic planning and dictates, to a large extent, changes that must be made to the IT portfolio to achieve maximum return on investment.

While this kind of strategic analysis is critical, more fundamental analysis and planning must also take place at the portfolio and investment level. Investments currently in the portfolio must be analyzed to assess how they are performing. There are multiple methods for making such assessments, including operational analyses and post-implementation reviews. An agency-wide portfolio analysis provides for examination of other important issues that might not otherwise be addressed, such as the existence of duplicative or overlapping investments, or program areas that lack sufficient automation support.

Results of the various analyses are presented to the ITIRB as they are completed, to educate and prepare the ITIRB for its important role during the CPIC selection phase. Completion of the enterprise architecture and portfolio analyses and presentation to the ITIRB enable the CPIC-SG to prepare a preliminary plan depicting needed updates to existing systems, opportunities for new investments, and necessary infrastructure upgrades and enhancements.

Selection Phase

Of the four phases, selection is the most visible because it is the decision point for IT investment for the coming fiscal year. Planning information is presented and discussed, and the ITIRB makes key decisions, such as what changes it wants to make to improve and upgrade existing assets, whether any investments should be withdrawn from the portfolio and discontinued, and what new investments will be added to the portfolio. The decisions must be made within the budget framework, so prioritization and tradeoffs are a critical element of the selection phase.

The CPIC-SG serves as facilitator for this phase by scheduling meetings, collecting, preparing, and providing briefing materials to ITIRB members in advance and providing staff services to the ITIRB. At the meetings, various groups and participants might be involved in making presentations and presenting investment justifications. Once all information has been presented and discussed, the ITIRB must decide which initiatives to approve and how much funding to allocate to each.

The decisions, once made, serve as the basis for preparing the annual IT budget as part of the agency’s overall budget formulation process. They also satisfy OMB reporting requirements for IT investments as stipulated in OMB Circular A-11.2

Control Phase

An IT portfolio consists of investments that are in operational, steady-state mode, new investments that are under development but not yet implemented, and mature systems that are being modernized or substantially enhanced. The latter two categories represent investments that have the highest degree of risk because software and systems development are inherently risky for many reasons, including the difficulty associated with requirements specification, the introduction of new technology, and/or design complexity. The CPIC control phase consists of reasonable approaches for monitoring investment progress, identifying potential problems, and managing and mitigating associated risks.

Various activities and methodologies, discussed in subsequent chapters, are available to an agency for controlling investment risk. As part of the control phase, the CPIC-SG is responsible for preparing portfolio progress reports and providing them to the ITIRB, along with recommendations for any necessary actions that the ITIRB needs to consider. For example, if midway through the fiscal year a project is reported to be behind schedule and/or over budget, the project manager might be required to attend an ITIRB meeting to explain why this has occurred. The ITIRB may then require the project manager to take explicit actions to address the problems.

Other important activities that take place during the CPIC control phase are the integrated and/or independent baseline reviews (IBRs) of investment cost estimates and schedules. The investment owner and IT project manager typically conduct an integrated baseline review jointly to understand and assess the adequacy, accuracy, and risks of an estimated performance measurement baseline. The objective is to ensure that the work scope, schedule, technical requirements, cost, and other resource estimates are accurate and reliable. If independent evaluators conduct the review rather than the investment owner and IT project manager, it is generally referred to as an independent baseline review, but it serves the same purpose as the integrated baseline review.

Routine reviews of baseline estimates are an important part of an effective CPIC process because they provide a second opinion to the ITIRB regarding the efficacy of the project team’s cost and schedule estimates. This is an important risk-mitigation strategy.

Evaluation Phase

The CPIC evaluation phase involves analyzing the results of past decisions, identifying issues and lessons learned, and providing suggestions for improvement to both the ITIRB and CPIC-SG. For a recently implemented investment, a post-implementation review (PIR) provides an opportunity to assess what worked and what did not work, evaluates how well the investment is achieving its planned performance goals, and determines if the ITIRB needs to be made aware of any aspect of investment behavior or performance.

Another important evaluation responsibility is to schedule and conduct operational analyses of in-place assets that have been operational for a long time. Such reviews offer an opportunity to determine if the underlying technology is still cost-effective, to evaluate how well the investment is meeting program and other goals and performance expectations, and to identify opportunities to improve the investment. An important result of an operational analysis is to forecast how long the investment should remain in place before being considered a candidate for enhancement or modernization.

Evaluation also provides an opportunity to tackle special projects, such as looking at security and privacy across a set of investments, examining consistency and interoperability, or focusing on a wide variety of other issues that might merit ITIRB attention. Such issues might generate ideas for potential new initiatives that need to be carried into the planning and selection phases of the CPIC process.

As the preceding discussion indicates, evaluation is a data collection and analysis phase that should generate ideas and information for consideration during subsequent phases of the CPIC process. It is critical that the evaluations render assessments of IT performance that affect the overall return on investment.

CPIC Artifacts

CPIC is clearly a somewhat complex process that requires investment of time and effort by a number of individuals and groups. To minimize its overall impact on the time and responsibilities of ITIRB members, a number of key artifacts (e.g., documents, briefing materials, reports) are used to communicate the results of analysis and to shape discussions and decisions. These artifacts range from high-level briefing documents to detailed business cases, and they are generally designed to suit the audience for which they are prepared. Figure 1-2 gives examples of CPIC artifacts.

Artifacts provided to the ITIRB must be prepared in summary form with associated supporting documentation because the senior officials who serve on the ITIRB have a limited amount of time to devote to their CPIC responsibilities. On the other hand, the CPIC-SG must analyze information in more detail to establish more substantive justifications and rationales.

From a strategic perspective, the ITIRB must rely on two key artifacts: the agency enterprise architecture (EA) and the results of the portfolio analysis, which are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6, respectively. The agency’s chief architect, working in concert with program and technology representatives from throughout the agency, generally prepares and documents the agency’s EA, aligning it with the agency strategic plan and the IT strategic plan. The EA includes a depiction of how business is conducted today (as is) and how it will be conducted in the future (to be) from both a programmatic and IT perspective. It also includes a transition strategy for moving from the present to the future. Assuming that the ITIRB has ratified the EA, it can be used to ascertain whether a particular investment supports or contradicts the EA transition strategy, which is useful information for making approval and funding decisions.

The portfolio analysis results are useful because they provide information about portfolio and investment performance, including in-use assets that are quietly supporting their intended purpose and in-process investments that are being developed or acquired. The portfolio analysis results identify any inherent portfolio design flaws or gaps and propose potential actions that the ITIRB should consider. The ITIRB can use this information to question the CIO and other agency officials about identified gaps and the status and priority of addressing them.

Another important artifact is the agency’s IT capital plan (sometimes referred to as OMB Exhibit 53), which represents the entire IT budget. Its importance to the ITIRB is obvious because one of the primary ITIRB responsibilities is to oversee IT spending. This includes making sure that current spending is not at risk and determining the future level of spending that will be submitted to OMB as part of the budget process.

One of the more controversial artifacts is the business case. The controversy stems from the level of preparatory in-depth analysis and documentation that is involved. OMB has established a business case format in Circular A-11. A business case typically encompasses a description of the initiative; a budget covering the full life cycle investment costs; anticipated outcomes formulated in measurable terms; a risk analysis; an acquisition plan; identification of alternative technological approaches for achieving the outcomes with an associated cost-benefit analysis for each alternative; an estimated work breakdown structure; an estimated budget; and an anticipated schedule. Many agencies do not usually develop this level of detail for a new system or for modernizing an existing system, and many technologists view preparation of a business case as unnecessary and excessive documentation. (A discussion of the business case is presented in Chapter 8.)

Other key artifacts include project status reports that communicate EVM performance information, operational analysis results, and PIR results. Each presents information about the status of in-development investments (project status reports), steady-state investments (operational analysis reports), and recently implemented investments (PIR reports). All are useful during various CPIC phases to inform the ITIRB about investment performance and to identify cases where ITIRB involvement and possible actions are necessary.

Implications of the CPIC Process

Congress develops tax and spending legislation through procedures prescribed by the Congressional Budget Act.3 Each year, Congress formulates, debates, amends, and enacts by a majority vote a series of annual spending bills funding federal agency operations. After agency budgets are finalized through this process, subsequent subordinate spending responsibility and decision-making is transferred to the agencies in accordance with their priorities and needs.

This process is in many ways a substitute for the traditional market-based forces that govern private sector consumer behaviors. In a free-market system, the laws of supply and demand govern the nature of transactions. Buyers pursuing their self-interest conduct business with sellers that offer the greatest value, thereby forcing out other sellers that charge too much for their products, don’t complete projects on time, or offer insufficient products and/or services. In federal agencies, IT buyers typically rely on a single seller—the central IT organization—and they are often preoccupied with program-related responsibilities and not sufficiently involved in the IT purchasing process.

The CPIC process provides federal agencies a significant opportunity to improve the return on IT investments by introducing many of the benefits of a free-market economic system. Decisions regarding new investments are made from an agency perspective, not a program perspective, which improves the likelihood that agency IT investments will have the most significant impact on agency operations. End-users are more involved in the decision-making process, which improves the likelihood that IT resource allocations benefit from free-market, consumer-driven forces. An effective CPIC process helps federal agencies make the right IT choices.

The difference between “doing the right thing” and “doing things right” is key. The former refers to making the right choices, and the latter refers to following through on those choices efficiently. CPIC helps federal agencies make the right choices and follow through on them efficiently by establishing a structured decision-making and monitoring process.

A well-designed CPIC process requires sufficient analysis via a business case, sound judgments based on facts and legitimate information, and monitored investment performance, especially during high-risk periods when assets are developed or acquired. CPIC also requires PIRs and operational analyses of in-use assets. These reviews ensure the mitigation of project risks, or at least that the ITIRB is aware of risks and can take action when necessary. PIRs and operational analyses also ensure that the agency is proactively monitoring the performance of systems and assets that have been operational for years or even decades.

CPIC implementation does not undermine the CIO’s role or weaken the agency’s IT function. Rather, it gives the CIO a seat at the table commensurate with the important role that IT now plays in agency operations and mission achievement. CPIC forces program managers and other users of IT services into the decision-making role and links IT resources to business needs. By positioning EA as an agency process and tool, the CIO’s job of integrating programmatic activities and IT resources is made easier. Also, the critical strategic input necessary to develop an EA is more readily available and more accurate because the EA is “owned” by the ITIRB rather than by the CIO, ensuring program input and involvement.

CPIC requires a significant change in organizational culture for many agencies. It forces centralized management of the agency’s IT budget and causes senior program managers to become more involved in how IT resources are prioritized and used across the agency. It also requires all involved parties to treat IT systems and resources as capital assets that must be managed throughout their life cycle rather than as systems that need to be built and then implemented in a production environment and essentially relegated to being part of the agency’s day-to-day operations.

The most profound cultural changes, however, occur within the IT organization and the associated user and liaison groups that interact with the IT organization on a daily basis. Many IT projects are established to develop and implement a specific application. IT staff are involved from inception through deployment, but typically their involvement ends when, or shortly after, the system is put into the production environment. Some developers may remain assigned to support the maintenance needs of the system, but most project managers and developers transfer to new projects.

While this may seem like a practical way to do business, it actually treats the system like a development initiative rather than as a capital asset. The project team perceives that it must do the requisite analysis, design, development, testing, and deployment necessary to launch the new system, and it develops a budget and schedule for doing so. But the team does not think that it is responsible for analyzing the impact and outcomes that the system will have once it is deployed into the production environment or for assessing and estimating the budgets and schedules of the system once it moves into early and mature production status. In short, the project team does not view its role as an investment management team, but rather as a system development team.

Given this perspective, IT project teams sometimes resent having to develop the kind of detailed business case necessary to evaluate a capital investment. They generally have little experience in identifying and quantifying expected project outcomes, broadly analyzing alternative solutions and conducting associated life cycle cost-benefit analyses, preparing acquisition plans, or conducting rigorous risk analyses. Therefore they view CPIC implementation as an intrusive and unnecessary change to the way that they have always done business.

Another significant impact of CPIC results from its capacity to monitor and control the behaviors of a project team. In the past, federal agencies tended not to closely scrutinize project budgets and schedules and, as a result, project teams could fall significantly behind or overspend before any problems were brought to the attention of senior managers. CPIC requires rigorous risk analysis, mitigation strategies, and the development of a risk-adjusted budget and schedule. The initial baseline estimates are independently reviewed to provide a second opinion regarding their accuracy and to guard against excessive optimism by a project team. Project progress is monitored using reliable EVM techniques that accurately depict cost and schedule variance. Given increased project performance transparency, project teams in an agency employing CPIC have an incentive to avoid falling behind or overspending.

Finally, those who are assigned responsibility for implementing CPIC are often frustrated by how much time and effort must be expended to implement the process, develop artifacts, and conduct meetings. At each phase of the CPIC process, significant resistance to changes in traditional business practices will crop up. Successful CPIC implementation requires an awareness of such challenges, perseverance in the face of resistance, and commitment from senior agency officials. It also requires a firm commitment to end-user involvement, to a centralized, controlled IT budget, and to the treatment of IT resources as capital assets.

ENDNOTES

1. Government Accountability Office, Testimony of Randolph C. Hite, “The Federal Enterprise Architecture and Agencies’ Enterprise Architectures Are Still Maturing,” May 19, 2004. Online at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04798t.pdf (accessed December 2007).

2. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11: Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, July 2007. Online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a11/current_year/a11_toc.html (accessed December 2007).

3. Congressional Budget Act (as amended), U.S. Public Law 93-344, July 17, 1985. Online at http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house/hd106-320/pdf/hrm89.pdf (accessed December 2007). See also the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, U.S. Public Law 67-13, June 10, 1921. Codified in Title 31—Money and Finance of the U.S. Code. For more information, see http://www.access.gpo.gov/uscode/title31/title31.html (accessed December 2007).

i The first step in the annual federal budget process consists of preparing and submitting the President’s budget to Congress in February. The President’s budget is formulated based on discussions with cabinet and agency leaders about their budget requirements for the next fiscal year. The President’s budget represents a detailed proposal of the administration’s spending plan for the fiscal year and is intended to persuade Congress to consider and enact the requested funding.