Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Lead without Blame

Building Resilient Learning Teams

Diana Larsen (Author) | Diana Larson (Author) | Tricia Broderick (Author) | Natalie Hoyt (Narrated by)

Publication date: 09/27/2022

Workplace finger-pointing stifles creativity, reduces productivity, and limits psychological safety. Although no one sets out to be judgmental, learning new habits is hard. Two experienced leadership and agilists coaches share a road-tested leadership model that continuously embraces humility and failure as part of the growth process to deliver results.

By facilitating blame-free retrospective meetings, leaders chart a productive path forward. They amplify three essential motivators of purpose, autonomy, and co-intelligence within their team. Layered on with four resilience factors: inclusive collaboration, transparent power dynamics, collaborative learning, and embracing conflict. After applying these strategies, learning leaders will help their teams and themselves become more resilient and better equipped to handle any unexpected and challenging tasks that comes their way.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Workplace finger-pointing stifles creativity, reduces productivity, and limits psychological safety. Although no one sets out to be judgmental, learning new habits is hard. Two experienced leadership and agilists coaches share a road-tested leadership model that continuously embraces humility and failure as part of the growth process to deliver results.

By facilitating blame-free retrospective meetings, leaders chart a productive path forward. They amplify three essential motivators of purpose, autonomy, and co-intelligence within their team. Layered on with four resilience factors: inclusive collaboration, transparent power dynamics, collaborative learning, and embracing conflict. After applying these strategies, learning leaders will help their teams and themselves become more resilient and better equipped to handle any unexpected and challenging tasks that comes their way.

PART 1: ESSENTIAL MOTIVATORS

Chapter 2: The Shift for Leading Resilient Learning Teams

Chapter 3: The Benefits of Alignment

Chapter 4: The Strategy of Continuous Learning

Chapter 5: Accelerating the Essential Motivators with Retrospectives

PART 2: RESILIENCE FACTORS

Chapter 6: The Collaborative Connection Resilience Factor

Chapter 7: The Conflict Resilience Factor

Chapter 8: The Inclusive Collaboration Resilience Factor

Chapter 9: The Power Dynamics Resilience Factor

Chapter 10: Where do you go from here?

Appendices

CHAPTER 1

Break Free from Blame

Leaders want results. Too many leaders have the idea that blame or shame helps people do better. Based on research and our accumulated experience, this is not accurate.

Blame: When we blame, we censure, invalidate, or discredit others, stating or implying their professional, social, or moral irresponsibility.

Shame: When we feel shame, it’s a self-conscious, self-loathing emotion. Shame promotes feelings of distress, exposure, mistrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

In a one-on-one session with a leader, Diana asked, “What do you want to focus on today?” The leader, Priyanka, responded, “The fact that I’m stupid.” A million things were running through Diana’s head, but she simply responded, “Tell me more.” Priyanka talked for quite some time. She explained how she had failed at helping her team. She assumed that she wasn’t knowledgeable enough. She shared that she was blamed for ineffectively communicating with the team members. She noted how exhausted she was and that there was no break in sight. She repeated that she failed the team. She kept returning to the shaming statement that she was stupid.

Diana took a step back to clarify the purpose of Priyanka’s actions. She asked, “How were you trying to help? What were the outcomes you were trying to lead the team to accomplish?” Priyanka rattled them off quickly. One, her team asked her to do this. So she wanted to be responsive and helpful. Two, saving team members time by communicating on their behalf. Three, keeping everyone and everything aligned on the goal. Four, knowing the status and controlling the situation.

Then Diana asked, “With a leader being the go-between, which of these benefits would be achievable? Even with all the intelligence in the world.” Priyanka paused. She raised her head just a tiny bit. She started to say, “Maybe saving . . . ,” but trailed off. She interrupted herself to acknowledge, “Actually, none of these.” She sighed and paused for a long, silent moment. “This approach was never going to work.”

As the conversation continued, Diana heard these beautiful words: “I’m not stupid. Here’s what I’m going to try next time.”

Priyanka wanted to help her team, her organization, and her customers. Her intent was amazing. Her goals were what many expect from leaders. Priyanka’s choice to be the go-between is not out of the ordinary. And the failure to achieve results with this approach is unsurprising. Not being a bottleneck was the issue that needed resolution. Yet their blame and her shame distracted from solving this real issue.

Faultfinding is a popular sport. It gives the illusion of making things better, but it rarely leads to real improvement. In fact, it engenders destructive emotional responses. Feeling blamed by others leads to hiding out and inaction. Fearing we’ll become the target of blame leads to deflecting and hiding mistakes. Accepting the shame of “doing it wrong” decreases our sense of self-worth. Everyone on Priyanka’s team, including Priyanka herself, defaulted to deciding who was at fault and why. But Priyanka was not stupid and wasn’t a poor communicator. This focus created wasted energy.

When we feel blamed by others or shamed by ourselves, we cripple our ability to perform well. We become incapable of innovative, creative thought. Movement in a new direction comes with too much threat. Faultfinding, judgments, blame, and shame work together to prompt a negative downward spiral. All continue a vicious blame cycle that is unproductive. We must break free to achieve resiliency and results.

Why Breaking Free of Blame Is Critical

What do we mean by breaking free of blame? That people stop taking time to find the person to skewer with blame, including themselves. We’ve seen the waste and damage in business failures, as well as damage to personal and interpersonal relationships.

According to Daniel Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow, people have a propensity for substituting easier problems for hard ones.1 Reflecting back on a problem, we may find ease in blaming people or shaming ourselves, judging people for not doing “what is common sense” or “obvious to everyone now.” People don’t examine the systems involved that allowed this failure to happen. Instead, they often go for the easier answer: the person should have just done their job.

In Priyanka’s situation, she determined she was stupid, that she, singlehandedly, was the cause of all the problems. She publicly accepted the blame, and she privately and publicly shamed herself. As a leader, Priyanka set an example that assumes mistakes are horrible. And a mistake maker is always punished. Yet none of this actually improves the results.

If the blame and shame continued, Priyanka would be on a destructive path that could even destroy her self-confidence, abilities, and value to others. If the vicious blaming and shaming cycle continued, Priyanka would feel unsupported. She could collapse under the weight of everyone’s unrealistic expectations. Then Priyanka might begin to feel victimized and to complain and justify. She might quit. Or worse, she might stay but remain in a head-space that brings herself and others down, expending energy on the target of blame and shame instead of on possible solutions. What kind of results are achievable when this is all happening?

Too many people with high potential as leaders walk away when they are stuck in this cycle, leaving individuals, teams, and organizations to suffer.

Let’s examine another story.

A client assigned a task to Kevin. This task was to write an article on a team collaboration activity. Kevin understood the value of this article, so he agreed to the assignment.

Kevin struggled to write the article. He had never self-identified as a strong writer. So he delayed and delayed getting started. Finally, out loud to himself, he said, “I have to do this. I don’t have a choice. Just write something.” He wrote. At the next meeting, he gave it to the client. The client became confused. This article did not reflect what Kevin was capable of or what they expected. They blamed Kevin for not paying attention to the task details. They asked him to try again. So he did. Again, he delayed. Now he was in full shame mode, repeating to himself frequently how horrible he was for procrastinating, and revisiting how crazy the client was to ask him to do this.

He met with the client again. He walked into this meeting with a sense of dread. He was preparing to explain why he was horrible and feared being further judged.

Few people think, “Who can I blame today?” If you had asked the client if they forced this task on Kevin, they would have said no. It was only a request. If you had asked the client if they were judging him, they would have said no. They were giving feedback and challenging him to improve. Unfortunately, that’s not what he experienced. People begin to internalize blame in the form of shame. Shame leads to lower engagement and confidence. The more Kevin disappointed his client, the more disappointed he was in himself. The more disappointed he became in himself, the more he resented the task at hand, and the worse the result became. By blaming and shaming, we pretend we can prevent the issue again. Yet each revision Kevin attempted diminished in value.

For results, leaders need to break this cycle. Breaking free from blame means embracing uncertainty and complexity. Breaking free from blame means focusing on learning and what to do next.

A development team was dependent on the marketing team to provide text for a feature in the product. Unfortunately, the marketing team had missed three sequential deadlines for providing this text. Development team members were frustrated. They complained to each other about the marketing team. They began making jokes and snarky comments.

As the leader of the team, Tricia observed repeated blaming behaviors. To get the team focused back on learning and the goal, she opened a discussion. Tricia asked the team to list reasons that marketing had missed deadlines. Answers flowed easily and were usually judgmental. Tricia then asked the team if they knew what bigger issues the marketing team might be facing. They acknowledged that they had no idea. During this conversation, one of the team members asked a valuable learning question: “We don’t control the marketing team. We don’t know what is really happening over there. But what can we do to help this situation?”

By ceasing to expend energy on judgment, the team discovered helpful options for both teams. Clearly, there is more to this story than one simple question. But first, we have to understand why people jump to blame and shame in the workplace.

Popular Fallacies

How did so many organizations get to a place where blame and shame regularly occur? Many organizations accept a foundation of beliefs that have wreaked havoc. In the past, these beliefs were possibly suitable for some situations. But now they have truly become outdated as they impede the achievement of results.

Fallacy: Everything can and should be more efficient. During the industrial era of organizations, businesses faced many challenges. One of the biggest was optimizing task-oriented work. Task work entails the performance of repeatable understood activities to reproduce a known output. Leadership focused on consistency and efficiency—for example, improving the speed of assembly-line work.

But not all work is task oriented. Knowledge work entails having a rough idea of the goal upfront, then working together to discover value. This means constant learning, unclear activities, and new, evolving outputs.

Knowledge work requires different leadership and processes. Thus, when leaders try to manage knowledge work as task work, blame and shame increase. The goal of being efficient (fast) before being effective (valuable) forges a losing strategy—for example, asking people for yearlong detailed estimates on knowledge work (crazy!), then blaming people for missing estimates that were always only guesses (even crazier!).

Acclaimed management thinker Peter Drucker wrote, “The most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution will be its knowledge workers.” Drucker described a “knowledge worker” in 1966 (The Effective Executive) as an employee who thinks, using cognitive rather than physical abilities.2

Fallacy: Everything hinges on shareholder value and profitability. When the balance of attention goes to increasing shareholder value, stakeholders suffer. Stakeholders include employees, customers, vendors, and the surrounding community. A focus on shareholder value intensifies the problem of prioritizing efficiencies over effectiveness. Organizations focus on quarterly profitability rather than longer-term, sustainable performance. Businesses tend to manage by driving down costs to show bottom-line savings for each quarter. They miss opportunities for growing the top line to increase revenue. When cuts become untenable, blame increases—blaming employee productivity, blaming vendors for pricing, blaming customers for not knowing up front exactly what they need. This drives knowledge workers to urgent, short-term productivity. This short-term approach benefits only shareholders. Ultimately, both shareholders and stakeholders lose.3

Fallacy: Everything is a “project.” Traditionally project success is defined by three goals: meets requirements; under budget; and on time. Nowhere in this definition is customer satisfaction. The definition assumes the output is completely known (task work). If that is true, then “meets requirements” assumes customer satisfaction. But this definition fails with knowledge work. The reality is that often stakeholders don’t know what they don’t know about what they need. Value discovery comes from cycles of feedback. Attention to product delivery produces more effectiveness than a focus on project success. Yet many organizational processes center on projects, not products. Thus, blaming occurs—blaming stakeholders who changed their minds, blaming employees for not asking the right questions, blame that work doesn’t fit into the financial accounting structures.4

Fallacy: Every leader must have all the answers. There are many reasons for leadership role promotions. Three common ones are time in role, individual expertise, and problem-solving ability. In task work, leadership had all the answers due to previous experience. The command-and-control style of leadership is sufficiently effective for task work. Yet in knowledge work, when leaders don’t have the answers, they become the target of blame and shame. When teams don’t meet their goals, leaders blame employees, and employees blame leaders for having unrealistic expectations. In knowledge work, leaders cannot control and guarantee results. No one can. Nor will one person ever have all the answers. Leaders want knowledge workers closest to the outcomes to achieve the goal together.5

Learning Leaders 4Cs

Learning leaders support leaders at all levels to become learning leaders too. They build resiliency from outside and inside the team.

They build resiliency with the key elements that increase the odds of success. Chip Bell, in “Great Leaders Learn Out Loud,” exhorted leaders to “learn out loud.”6 We find “learning out loud” makes a difference. To show a commitment to learning, learning leaders embrace, model, and activate four elements: courage, compassion, confidence, and complexity (the Learning Leaders 4Cs; Figure 1.1).

Courage

Courage showcases the favorable behaviors we want to reveal in teams. To show courage, leaders stand up for learning, their own and others’. Learning leaders advocate for team, organization, and individual learning time. They show curiosity about discovering what’s needed for the next deliverable. They share their willingness to explore their vulnerabilities and ask for help.

Compassion

Compassion encourages valuable concern and interactions during challenges and failures. With a compassionate approach, the leader recognizes the difficulties of learning for anyone. They understand that developing new skills takes time, and it may even negatively affect short-term production. They respect that people, including themselves, may have leftover fears about learning. They provide a safety net for learning.

Figure 1.1 Learning Leaders 4Cs

Confidence

Confidence develops in a team’s ability to learn whatever they need to meet the challenge. With confidence, growth in professional skills and interaction behaviors emerges. The learning leader’s confidence expands along with the team’s ability to move ahead. Simply put, they believe in others.

Complexity

Complexity awareness allows for discovery and unleashing the power of emergent valuable solutions. With complexity awareness, critical thinking behaviors take on renewed emphasis. Learning leaders act from a systemic viewpoint. They look for the systemic roots of problems. They understand that more actionable information surfaces as the team continues to learn.7

Before a half-day sales team reflection meeting, Tricia was finishing preparations. As each participant arrived, they approached Tricia with similar cautions: “John is not going to like this.” “John doesn’t do activities.” “John will probably not participate.” Her response to each warning was, “I have confidence in this team’s ability to work together.” As he was the only one who didn’t approach her, she knew who John was immediately.

Tricia became a little more nervous with each successive warning. Yet she had taken several things into consideration that she knew would help John and others. Tricia had considered how to enable learning and foster a collaborative tone. As a result, she let the nerves go and felt confident that John would be able to contribute.

As the meeting began, the anxiety in the room was noticeable. Teammates wondered what John would or wouldn’t do. During the first major activity, Tricia invited people to shout out their opinions. She noticed John hesitated to share his thoughts. She acknowledged that learning can be challenging, as we have to slow down to speed up. Then she instructed everyone to discuss the topic in pairs. The pair would decide who would share its opinion with the larger group. Tricia observed John engaging with his partner. When it came time to share, John’s partner shared John’s opinion. The room acknowledged each opinion. Tricia reinforced the importance of hearing various opinions. She noted that the variety would be valuable for the team in determining how to proceed on a new solution. Throughout the rest of the meeting, John continued to engage in each activity.

At the end, John approached Tricia. In front of the team, he said, “I usually don’t like these things, but somehow I liked today. I don’t know how I feel about you.” Then he walked away with a smile on his face. This remains one of the best compliments Tricia ever received.

It is important to note that John was not difficult for the sake of being difficult. He did not enjoy any large room full of people shouting over each other. He did not enjoy meetings that never seemed to get results. Who does? The difference is that John showed courage by not playing along. We respect this response. There will never be a single perfect design for all situations.

The 4Cs create spaces for people to thrive and contribute together. Learning leaders continuously and courageously embody these four elements. By reassuring team members that things would be OK, Tricia demonstrated her confidence in their team’s ability to figure it out. By adjusting the activity to pairs, she showed compassion for engagement challenges. By expressing the importance of hearing all voices, Tricia showcased the behaviors desired. By noting the value of variety, she brought complexity awareness to the tasks at hand. As a result, John was able to fully engage, collaborate, and learn with the team. The team benefited from his contributions. Together, they realized that all their perspectives made better solutions.

With behaviors that support the 4Cs, learning leaders foster the right environment.

Introduction to Leadership through Learning

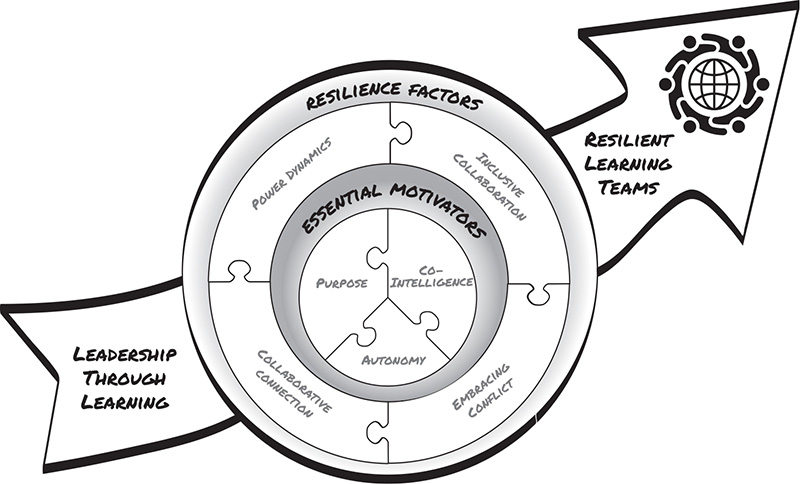

Breaking free from blame, learning leaders begin a journey into leadership through learning (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Leadership through Learning

Leadership through learning reflects the leader’s role in growing team resilience to discover lasting value. Learning leaders build resilient learning teams. Resilience is the human ability to meet and recover from adversity and setbacks. We need learning across the board; for leaders, for our teams, and for our organizations.

Resilient learning teams have the ability to sustain under pressure and chaos. They overcome major difficulties without engaging in dysfunctional behavior or harming others. A resilient learning team provides a foundation for enabling business agility.

The high degree of uncertainty in this world leads to the need for flexibility and resiliency—the ability to bounce back from adverse events. As chaos unfolds, it requires people to collaborate and learn together. In a VUCA world, “speed to learning” becomes a crucial indicator for enabling business agility.

Business Agility

Business agility is the ability of an organization to sense changes internally or externally and respond accordingly in order to deliver value to its customers.

Business agility is not a specific methodology or even a general framework. It’s a description of how an organization operates by embodying a specific type of growth mindset that is very similar to the agile mindset often described by members of the agile software development community. It’s appropriate for any organization that faces uncertainty and rapid change.8

Our use of the term VUCA comes from the article in Harvard Business Review by Nathan Bennett and G. James Lemoine.9 In it, the authors introduced the acronym into the business world. Coined by the US Army War College, VUCA was intended to capture a set of characteristics. It stands for “volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.” It described the conditions squads of soldiers encountered after deployment on a mission. Following plans made at headquarters cost lives. HQ officers could not take into account the rapidly changing situations these squads found in the field. Army trainers acknowledged that these conditions altered assumptions about the chain of command. Soldiers needed new skills, understanding, and mindsets. Training with VUCA allowed them to react and respond to the scene they discovered. For resilience in business, as well as warfare, leaders need to equip themselves differently. Both officers and business leaders need to rethink their skills, their approaches, and their thinking about leadership.

All teams face, or will face, VUCA barriers to success. Leadership through learning encourages and enables whole team learning. A learning leader embraces complexity awareness and aids the team in learning how to overcome barriers together. Peter Senge coined the term learning organization, defining it as “a team of people working together collectively to enhance their capacities to create results they really care about.”10 Learning leaders create evolving learning organizations that minimize blame and shame. When people collaborate and learn together, they focus less on individual success or failures.

Business agility is a multifaceted topic for every organization. This book focuses solely on leadership’s ability to set up teams to be effective and resilient, thus providing organizations the team capabilities needed to achieve any business agility strategies.

We cannot provide one simple, comprehensive checklist for achieving leadership through learning. The challenge holds more nuance and situational variety than that. Yet leaders will find value in discovering essential motivators and resilience factors for building team resilience.

In Part One, we describe three essential motivators for teams. They lay the foundation for enabling high performance. We are not the first to illuminate three primary motivators for humans. But we’ve adjusted the concept for team learning and resiliency. We have expanded the mastery motivator into the essential team motivator of co-intelligence. Essential motivators help expand confidence, as the team shares responsibility for results. Besides, learning leaders understand that team resiliency is not automatic; it must be proactively and compassionately addressed.

In Part Two, the resilience factors take the team further. The resilience factors are collaborative connections, inclusive collaboration, power dynamics, and embracing conflict. These factors compose the “secret sauce” or the “underlying forces” for building resilience. These either courageously evolve teams or break teams in times of chaos.

Reflections for Your Learning

Begin your journey of breaking free from blame and shame today. Learning leaders focus intensely on resilient learning for the organization, teams, and themselves.

How does blame or shame manifest in your organization?

How would breaking free from blame create benefits in your organization?

Which leadership fallacies are present in your organization? Why? What is the impact?

How has learning influenced your leadership behavior? How have you supported others’ learning?

How do you embody the Learning Leaders 4Cs in your leadership?