Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Metrics for Project Management

Formalized Approaches

Parvis F. Rad (Author) | Ginger Levin (Author)

Publication date: 10/01/2005

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Parviz F. Rad, PhD, PE, CCE, PMP, is an independent project management consultant with over 35 years of professional experience. He has participated in the development and enhancement of quantitative tools in project management in a multitude of disciplines, including software development, construction, and pharmaceutical research. He has authored and coauthored more than 60 publications in the areas of engineering and project management. Dr. Rad holds an MSc from Ohio State University and a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dr. Ginger Levin, PMP, PgMP [second in the world] has over 50 years’ experience specializing in consulting and training in portfolio and program management, organizational project management, change management, and knowledge transfer. Dr. Levin had a career in the U.S. Government working in six agencies in transportation, including in the first agency-wide PMO at the Federal Aviation Administration and had a consulting firm in Washington, DC, focused on project management, maturity models and assessments, and organizational development. Since 1996, she works on her own in the project management field and is a PMI active volunteer. Dr. Levin also is an Adjunct Professor in project management for the University of Wisconsin-Platteville’s MSPM program and at the SKEMA Business School in Lille, France in its doctoral program. She is the author, editor, or co-author of 21 books and has a book series with Taylor and Francis. She works with UT-Dallas in its PgMP and PfMP boot camps. In 2014, she won PMI’s Eric Jenett Award for her contributions to the field. She received her doctoral degree from The George Washington University and won the outstanding dissertation award.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Organizations that follow a management-by-projects approach develop a performance-based style and continually grow in sophistication in the area of project management. Their project management philosophy is formalized, methodical, and dependent on practices that are objective and consistent. Project management metrics are key elements in this process, focusing on portfolio management, progress management, process improvement, and benchmarking. Organizational strategic objectives guide the selected focus of the metrics system, which in turn defines the structure of the measurement activities. In addition, metrics serve as historical benchmarks for purposes of future performance evaluation, with the expectation of facilitating continuous improvements.

Many organizations have used metrics for years, particularly in the areas of finance and manufacturing, but especially in those operations considered to be recurring in nature. These organizations know that metrics systems help improve the rate at which they achieve their business goals. Metrics also can identify important events and trends, helping guide these organizations toward informed decisions in all specialty areas, but particularly in project management.

Implementing a metrics system can help facilitate improvements in project success measures such as scope, quality, cost, schedule, and client satisfaction. Therefore, most project management professionals believe that enlightened organizations must implement a full complement of project life-cycle metrics in all branches of their organization where project accomplishment is part of the strategic mission.

In particular, sound metrics practices are essential to major project management activities such as project planning, monitoring, and control. Consistent tools and procedures, used by competent personnel, lead to lower overall project costs and increased corporate profits. Moreover, the span of the utility of metrics should go beyond scope-cost-schedule; metrics should be used in data collection as well as in predictive models. The scope-cost-schedule indices should always be addressed, however, as they represent the client’s vantage point.

Benchmarking is rapidly becoming a popular mechanism for process improvement within enlightened organizations. However, effective benchmarking requires a system for gathering and refining data on all facets of the organization, particularly on projects. If upper management is focused on achieving improved efficiency, a metrics program becomes a necessary business practice.

A good metrics system is one that contributes to the right decisions in a timely manner based on fact rather than feeling (Augustine and Schroeder 1999). The most effective metrics programs are those in which the metrics are tailored to the organization’s important issues and strategic objectives.

A well-planned set of metrics can help the enterprise recognize the level of sophistication of its collective capabilities, thus making organizational plans for producing and delivering products and services consistently realistic and achievable. It is paradoxical that the same financial considerations that might tempt organizations to abandon an extensive formalized metrics system are the very ones that help organizations realize cost-saving benefits through decreased expenses and increased profits.

Metrics can be collected and used throughout all phases and facets of project management. Metrics can measure the status, effectiveness, and progress of project activities to gauge the contribution of a project to the organization. Metrics also can serve as the basis for clear, objective communications with project stakeholders.

Ideally, and to offer more sophisticated capabilities for project tracking and control, project management tools should be integrated with business processes. In addition, metrics can promote teamwork and improve team morale by linking efforts of individual team members with the overall success of the project and, ultimately, the success of the organization.

Success in project management is contingent on an organization’s capacity to assess project status realistically and predict performance accurately. Accurate performance forecasts can, in turn, be used to meet commitments relative to products and services. Metrics also can be used to determine the health of organizational processes affecting the successful conduct of projects.

Finally, some metrics can serve as barometers of organizational project management maturity. To that end, groups of metrics can be used to show where an organization stands in terms of the sophistication with which the collective project teams handle any of the project management knowledge areas.

ADVANTAGES OF METRICS-BASED PROJECT MANAGEMENT

To support all project management functions, such as project selection and project portfolio management, metrics need to be integrated into project life-cycle processes. A properly designed metrics program can ensure that the organization continues to pursue the right projects, even when organizational and environmental changes occur on a day-to-day basis during the life of these projects. Admittedly, some of these unplanned, unexpected changes present new opportunities for efficiency and success; however, positive unexpected events are rare.

Ideally, the underlying objective of a project metrics system is to provide accurate, verifiable information that can be used for improved performance of the enterprise’s project management capability. One major advantage of a well-crafted, formalized metrics program is that its components provide unbiased testimony on the status of particular issues significant to the performance monitoring process. Such unbiased, objective data are necessary when dealing with divisional managers or clients who need to substantiate claims and requests. Probably the most significant advantage of a metrics system is that it makes explicit those items that are usually implicit in the decision-making process.

A good metrics system also can help formalize the rationale for making decisions by making available the expertise, knowledge, and wisdom of experienced project managers to all project management practitioners within the organization. This objective can be achieved through a metrics system that encompasses models and indices that, by design, provide accurate, unbiased information for project planning, execution, and monitoring. The availability of such data assists team members in minimizing project cost, shortening project duration, improving deliverable quality, and maximizing client satisfaction. Other goals of metrics system modules include refining the estimating processes for cost and duration, improving the project delivery process, handling unusual and unplanned project events better, enhancing communications, improving responsiveness, and achieving greater client satisfaction.

With the aid of an effective metrics system, each project can become an opportunity for learning that benefits the entire organization. Even failed projects hold potential for learning. There is no question that the cost of mistakes might be painfully high. However, if the circumstances and sequence of events are carefully documented, they constitute a rich data source of ways to avoid similar mistakes in future projects. Careful documentation also can provide insight into the current level of sophistication of the organization’s project management processes.

A well-crafted metrics program can help identify areas where processes and procedures are exemplary and should continue to be followed. Likewise, this same metrics system can identify those processes in which improvement is needed. Finally, the metrics system can highlight those areas in which new processes are required.

With projects increasingly becoming a way of life for many enterprises, the organizational benefits of logical project management achieved through metrics-based project management methodologies, tools, and techniques are easily demonstrated. To assist in identifying a guiding example for such a self-appraisal, the company should look to other organizations that have already implemented a sophisticated, successful metrics system and borrow and adapt from its components.

As this new metrics system is being developed, or as it is becoming more sophisticated, it is possible to provide definitive answers to questions that executives in organizations often ask, such as:

• Does the organization normally achieve the results planned?

• Does the organization regularly achieve the desired return on investment?

• Are the projects selected for implementation aligned with the organization’s strategic objectives?

• Do the selected projects support the organization’s business needs and objectives?

• Are project objectives being met?

• Are client success criteria being met?

• Are projects considered strategic assets?

The answers to the questions not only respond to management inquiries but also warn of forthcoming problems. This warning mechanism enables the organization to avoid, or at least manage, emerging problems. Early diagnosis affords the organization the chance to turn the problem into an opportunity, at least some of the time.

The optimum solution to emerging project challenges lies in the use of a metrics system that supports timely dissemination of project information and improved communication (Lucero and Hall 2001). In turn, improved communication leads to better performance by project teams. Ultimately, improved performance translates to more successful projects.

Notably, metrics by themselves do not impart any value to the organization, because they do little, if anything, to resolve the issue being monitored. Metrics do not make decisions, people do; metrics simply provide the foundation and rationale for decisions. Thus, the return on investment of a metrics system derives from the actions that project professionals take to manage the issue at hand.

It is a somewhat common practice, albeit a short-sighted one, that organizations experiencing poor cash flows or low profits will minimize expenditures for things perceived to be luxuries. For functional organizations, two activities that might appear to be luxuries—although in reality they are excellent investments—are research and training. Similarly, some project-oriented organizations will tend to minimize and discourage detailed project planning and comprehensive project closeout in the face of difficult economic times.

Again, such cost-cutting measures are often counterproductive, as the short-term benefit of conducting these two activities is the success of individual projects. The long-term impact relates to the overall project management maturity of the organization.

Although some metrics might seem inappropriate or superfluous in less mature organizations, metrics can provide benefits to all organizations independent of their level of sophistication in project management. Some organizations use formalized, detailed metrics only for major projects, even though metrics allow the execution details of all projects to be predicted. Ideally, metrics should be applied across multiple projects, all organizational divisions, and the entire span of the project life cycle to benefit the organization’s goals.

WHAT IS A METRIC?

In the context of project management activities, a suite of metrics can offer a glimpse into the full range of expectations of a particular deliverable item or the tasks that would produce that deliverable. Alternately, metrics can gauge the status of a deliverable item relative to expectations for scope, cost, and delivery date. In the latter case, metrics are aimed at small, measurable attributes that have a predictive or comparative capability.

The vast majority of project metrics focus on “things” attributes, which are quantitative and thus measurable. As “people” issues of projects move to the forefront of project management concerns, an increasing number of metrics deal with people attributes, which have behavioral characteristics such as morale, satisfaction, loyalty, trust, and leadership.

The assignment of ratings, numbers, and ranks for the latter category can be based on questionnaires or instruments that characterize and quantify selected attributes of team members, teams, or even the organization as a whole. Such quantification also can be based on the experience and judgment of a seasoned project manager entrusted to make such observations.

Metrics might measure particular attributes of the project team directly or indirectly. For example, a metric can measure Monday absenteeism, which, in turn, is an indirect metric for team morale (Neuendorf 2002).

When dealing with attributes that appear to defy measurement and ranking, it is important to use a binary metric for that attribute, one that signals the presence or absence of a project management feature or function. For example, one index of a metrics system could test the presence or absence of a formalized project estimating process using conceptual estimating techniques. Another index could measure the level of team participation in project review meetings, without attempting to explain or modify it.

Sometimes, a project metric is a numerical value that is computed from a collection of several pieces of data (e.g., earned value, percentage complete). In these cases, the resulting metric inherits the precision, accuracy, and validity of the primary indices that were used to derive it.

The individual indices and models that comprise a metrics system are sometimes cited independently, but usually they are presented in an integrated fashion, primarily because they are somewhat intertwined (Thamhain 1996). Almost always, multiple indices for project performance tend to produce synergistic results that can be used more reliably to make informed decisions about project direction, the program, the portfolio, and ultimately the organization’s strategic direction.

Organizations can be classified as immature relative to project management if they have not yet transitioned to formal project management. Ordinarily, these organizations tend to view technical expertise in the project’s subject matter as a fully sufficient skill for becoming a project manager. More than likely, these organizations have few, if any, procedures and metrics dealing with project management. If these organizations have any metrics at all, they tend to address project things, such as cost, schedule, and scope.

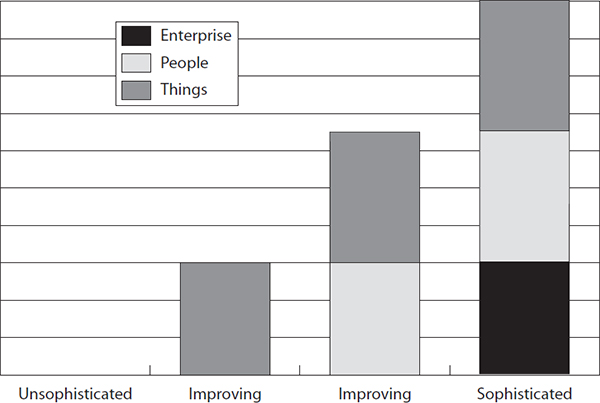

A slightly more sophisticated organization might have a full suite of procedures and metrics related to project things. These semi-sophisticated organizations generally accept that, if things issues are handled and measured properly, acceptable and reasonable success will be achieved. More mature organizations have metrics and procedures dealing with project people and project things, based on the assumption that people make projects happen. Thus, additional procedures and metrics might include human behavioral issues such as motivation, conflict management, professional responsibility, leadership, and trust (see Figure 1-1).

The final stage of sophistication is achieved when the project management processes and associated metrics also include issues that define the environment in which the project must operate, such as training, resource allocation, standard procedures, and overall organizational support.

Along this spectrum of maturity levels, all organizations use metrics that deal with the things aspects of the project such as cost, schedule, and scope. The difference in spectrum placement derives from the extent to which the things issues are supported, enhanced, and elevated by strengths in the areas of people and enterprise issues.

Figure 1-1

Project Management: Stages of Sophistication

Projects will not thrive, and often will not survive, in organizations that are indifferent, or possibly hostile, to projects. Conversely, projects will achieve their highest level of success in organizations that are friendly toward, and supportive of, projects. Mature organizations will have metrics and procedures that define all three sets of issues that relate to projects (i.e., things, people, and enterprise).

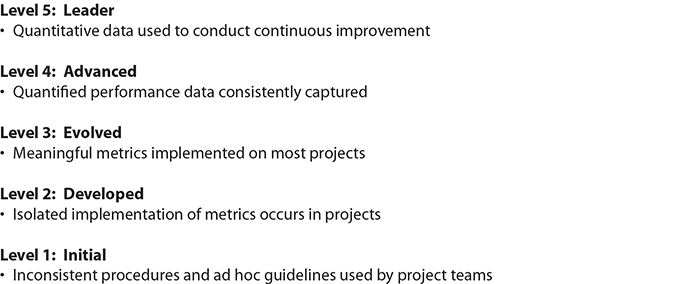

Figure 1-2 presents brief descriptions of the project management maturity levels following a staged model. There is a distinct interrelationship, although not necessarily a linear one, between the levels of project management sophistication and traditional maturity levels (Rad and Levin 2002).

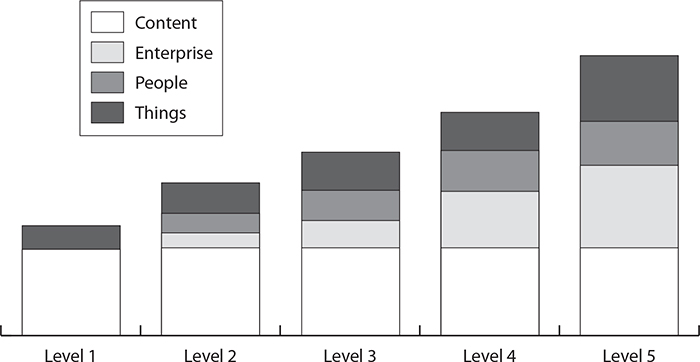

Figure 1-3 shows a stylized depiction of the relationship between maturity and the importance an organization places on people issues and organizational issues. Organizations that are at Level 1 (Initial) tend to support very few things-related metrics as part of their project management practices. In these organizations, proper handling of the technical content of the project is the primary project management concern. By contrast, Level 5 (Leader) organizations not only support competency in technical content but also value it in things, people, and enterprise issues.

The smallest component of a metrics system is an index, such as total cost or promised delivery date. A collection of indices, in a simple grouping or in a complex mathematical relationship, comprises a model. A model quantifies a multifaceted feature of a project, such as the components of a parametric estimating model or an earned value model. A full-scale metrics system contains many models and indices.

Figure 1-2

Project Management Maturity Level Descriptions

Figure 1-3

Maturity Level and Metrics Focus

METRICS CATEGORIES

Discussing project metrics as things, people, and enterprise allows the various perspectives of the project, the project team, and the organization to be isolated, magnified, and elucidated. The metrics included in each category can be a blend of individual indices and models. The lines of demarcation between the categories are not precise, but the categorization allows the reader to visualize the concepts and areas in more detail, by virtue of being symbolically isolated as a distinct area.

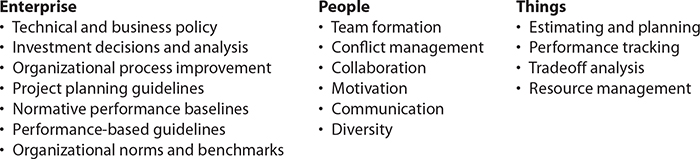

Things attributes address the performance of the project team in tangible terms of efficiency, productivity, and deliverables. Things attributes include topics such as progress monitoring, procedure enhancement, historical data collection, and best practice development (see Figure 1-4). People attributes address team members’ interrelationships with one another and focus on teamwork issues such as trust, collaboration, competency, communication, and conflict. Enterprise metrics address the environment in which the project team operates. These attributes describe an organization’s friendliness toward projects, involvement of project teams in the organization’s strategies, and recognition of the project management discipline by the organization.

The literature includes several other categorization patterns for project management metrics (Okkonen 2002), even though they involve the same universe of metrics. Ultimately, the decision how to categorize project management metrics in a particular organization should take into account the culture and operational practices of the individual organization in light of prevailing strategies and objectives.

Figure 1-4

Focus of Metrics

Metrics bring consistency and formality to project management. With metrics, important project decisions can be made on an informed basis. In essence, metrics bring objectivity to the tools for monitoring project progress and help advance the organization by allowing uniformity, accuracy, and repeatability.