Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Project Management for Small Projects, Third Edition 3rd Edition

Sandra F. Rowe (Author)

Publication date: 08/25/2020

Project Management for Small Projects shows you how to tailor bureaucratic planning processes to a sleek minimum while still keeping your project running like a well-oiled machine.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) recommends tailoring the planning processes to fit the size of your project, but it doesn't always fully explain how. Using too much process can be as detrimental to a project as not using a process at all. For years, this book has helped managers of small projects design processes that are neither too big nor too small but "just right." It provides simplified but compliant tools for immediate use in managing small projects. And since most small projects tend to be similar in structure or outcome, a template for one project can be used for future projects. This new edition of Project Management for Small Projects has been updated to align with the latest PMBOK. In addition, there is new material on Agile project management and on the essential leadership skills for small project managers.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Project Management for Small Projects shows you how to tailor bureaucratic planning processes to a sleek minimum while still keeping your project running like a well-oiled machine.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) recommends tailoring the planning processes to fit the size of your project, but it doesn't always fully explain how. Using too much process can be as detrimental to a project as not using a process at all. For years, this book has helped managers of small projects design processes that are neither too big nor too small but "just right." It provides simplified but compliant tools for immediate use in managing small projects. And since most small projects tend to be similar in structure or outcome, a template for one project can be used for future projects. This new edition of Project Management for Small Projects has been updated to align with the latest PMBOK. In addition, there is new material on Agile project management and on the essential leadership skills for small project managers.

Sandra Rowe, PhD, PMP, MBA, MSCIS, has more than twenty-five years of project management experience. Her responsibilities have included leading information technology and process improvement projects; developing project management processes, tools, and techniques; and designing, developing, and delivering project management training programs. She has taught graduate-level project management courses and speaks regularly on project management processes, project management for small projects, the project office, knowledge sharing, and lessons learned.

1  Introduction to Project Management

Introduction to Project Management

Most organizations rely on a variety of projects, both large and small. Although small projects have unique challenges that are not present in large projects, small projects can still benefit from a defined project management methodology. To achieve maximum benefits, the processes, tools, and techniques must be scalable and adaptable. The more successful you are with managing small projects, the more opportunities you will have to obtain larger projects. Almost everyone, to some degree, is involved with projects and should be prepared to manage them effectively. Project Management for Small Projects suggests an approach that allows the project manager to apply structure and discipline to managing small projects while balancing the needs of the project with the project management methodology.

As we discuss project management practices, I will use definitions from the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) publications and other sources.

Project Management Best Practices

A best practice is an activity that has proven to be successful over time. Some project management best practices include:

• Using a project management approach that captures the intent of the project business case

• Developing a project charter

• Documenting project requirements

• Identifying what is in and out of scope

• Using a project schedule to plan and monitor project activities

• Developing a project budget to control project costs

• Managing project risks

• Communicating to project stakeholders

• Using project management tools, techniques, and templates

• Tailoring a methodology to fit the specific needs of the small project to address the competing constraints of scope, schedule, cost, resources, quality, and risk

PMI defines the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK) as a term that describes the knowledge within the profession of project management. The project management body of knowledge includes proven traditional practices that are widely applied as well as innovative practices that are emerging in the profession.1

Therefore, the PMBOK® Guide provides a foundation which I used to build the techniques for small projects.

Project Overview

Projects are a more important part of business now than they ever have been. They exist at all levels of every organization and must be managed proactively, regardless of size. Normally when we think of projects, we think of large initiatives such as developing a new product or service, developing a new information system or enhancing an existing one, constructing a building, or preparing for a major sports event. Small projects are not always viewed as projects and therefore are not always treated as projects—especially smaller, more informal projects, which are often called assignments.

Definition of a Project

“A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.”2 A project can create:

• A product that can be a component of another item, an enhanced item, or an end item in itself

• A service or a capability to perform a service

• A result, such as an outcome or document

• A unique combination of one or more products, services, or results

A project has three distinct characteristics.

1. A project is temporary in that it has a beginning and an end. A project always has a defined start and end date. The project begins with a statement of work or some form of description of the product, service, or result to be supplied by the project, and it ends when the objectives are complete or it is determined that the objectives cannot be met and the project is canceled.

2. A project is unique in that the product, service, or result created as a result of the project is different in some distinguishing way from all similar products, services, or results. Unique also indicates that although a project might appear to be similar to another project because you are producing the same type of deliverable, it really is not. In both projects you are creating something that did not exist before. Even a revision to an existing deliverable is considered unique because the revised product is something that did not exist before.

3. A project is characterized by progressive elaboration. This means the project develops in steps and grows in detail. Progressive elaboration allows you to continually improve your plan by adding more detailed and specific information as more accurate estimates become available. When you are first given a project, you have limited information to work with, usually in the form of a high-level project description, the project objective, and some assumptions and constraints. The scope might be further defined, and the work activities for the project will have to be planned in detail as more specific information becomes available. Progressive elaboration allows you to manage to a greater amount of detail as the project evolves.

Projects also drive change in organizations. A project is used to move an organization from its current state to a defined future state.

Finally, projects enable business value creation. There is value derived from doing the work. Business value is the benefit that the results of a project provides to the project stakeholders and can be tangible, intangible, or both.

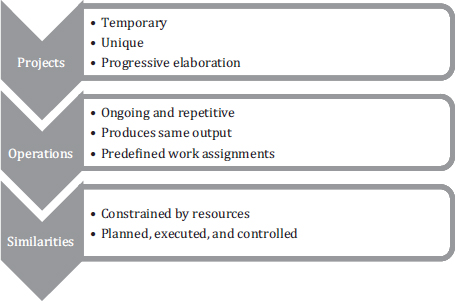

Another way to view a project is to see a project as something we do one time, as opposed to operational work, which is continuous and repetitive and is undertaken to sustain the business. Operational activities have no real completion date; they are ongoing. An example of a project would be to develop or enhance an accounting system. The operational activity would be to process biweekly payroll or pay monthly expenses. Both operational activities and projects are constrained by resources and are planned, executed, and controlled (figure 1.1). However, projects, due to their temporary nature, are initiated and closed.

Projects can intersect with operations in several ways:

• When developing a new product or result for an existing system

• While developing new or enhancing existing procedures

• When a project is completed and transferred to operations

Figure 1.1: Projects and operations comparison

Why Use Project Management on Small Projects?

Imagine being assigned a project to revise an existing process. You have a team of three subject matter experts to assist with the design and implementation. Where do you begin? What are you planning to deliver? When will this project be completed? How much will this project cost? What are the team members’ roles and responsibilities? The use of project management provides the discipline and tools for answering these questions.

Definition of a Small Project

Small projects are perceived to be relatively easy, but other than this there is no one way to define when a project is a small project. In some cases small could be defined on the basis of cost, such as costing less than $1 million. Cost is relative, however, and depends on the income of the organization. Small could also be defined by time, for example, taking less than six months to complete. For the purpose of this book, we will use the following guidelines to define small projects. A small project generally:

• Is short in duration, typically lasting less than six months, and usually part-time in effort hours

• Has 10 or fewer team members

• Involves a small number of skill areas

• Has a single objective and a solution that is readily achievable

• Has a narrowly defined scope and definition

• Affects a single business unit and has a single decision maker

• Has access to project information and will not require automated solutions from external project sources

• Uses the project manager as the primary source for leadership and decision making

• Has no political implications with respect to proceeding or not proceeding

• Produces straightforward deliverables with few interdependencies among skill areas

• Costs less than $150,000 and has available funding

If the project involves a few skill areas but the deliverables are complex, it is not a small project. If the scope is broad, the project usually involves more skill areas, so it would not be considered a small project. The more skill areas involved, the more effort will be required to manage the project.

A small project can be a portion of a larger project. For example, if a team lead is responsible for planning and controlling specific project activities and then reporting results to the project manager, the team lead is, in effect, running a small project. Most small projects center on changes in organizational processes or enhancements to existing systems. Other examples of small projects include:

• Developing a training course

• Implementing a project management office (PMO)

• Implementing a purchased software application

• Enhancing an existing information system

• Improving business processes

• Developing a website

• Evaluating an existing practice

• Developing a strategy

• Developing a project proposal

The following are detailed descriptions of two small projects.

Characteristics |

Criteria |

Duration |

Six months |

Team members |

Five part-time team members: project manager, instructional designer, two trainers, and an administrative assistant |

Single objective |

Develop introduction to project management training course |

Narrowly defined scope |

Training materials in alignment with other project management courses |

Single decision-maker |

Sponsor: corporate education director |

Straightforward deliverables |

PowerPoint presentation, facilitator’s manual, participant’s manual, and case study |

Interdependencies among skill areas |

Project Management Office |

Characteristics |

Criteria |

Duration |

Three Months |

Team members |

Four part-time team members: project manager and three subject matter experts |

Single objective |

Revise the planning process to include changes made to the corporate project management process and to be consistent with the current version of the PMBOK® Guide. |

Narrowly defined scope |

Planning process description and templates |

Single decision-maker |

Sponsor: project management office director |

Straightforward deliverables |

Planning process description, work breakdown structure. Process and example, brainstorming techniques, project-planning templates |

Interdependencies among skill areas |

None |

A small project can also be part of a program. (Refer to chapter 12 for a discussion on projects as part of a program.)

Definition of a Simple Project

This book differentiates between small and simple projects. Many of the best practices for small projects and simple projects are similar. When small projects and simple projects require different approaches, this book explains where and how.

Simple projects are even more straightforward than small projects. Simple projects are often called assignments. We usually do not think of assignments as projects, but assignments, like projects, have a definite beginning and end and produce a unique output. Assignments are usually short in duration and are completed by a small team consisting of three or fewer team members. Often only one person completes an assignment. (Refer to chapter 13, “The Power of One,” for more details on one-person assignments.)

Scenario

Kenny is an analyst with ambitions of becoming a project manager. He is aware of the definition of a project and the importance of using project management on small projects. He has been working on assignments and wonders if he could be more successful with completing his assignments if he used project management methods and tools. Can project management be used on an assignment?

The answer is yes. An assignment can be treated as a simple project.

Because we do not think of assignments as projects, we do not treat them as projects. Assignments, because of their size and duration, do not need all the formality required by projects; however, they can still benefit from a simplified form of project management. Treating assignments as projects provides you with the opportunity to clearly define expectations, better use resources, and eliminate the frustration of wasted effort and unnecessary rework.

Examples of simple projects include:

• Developing procedures or a reference guide

• Revising a business process

• Developing an electronic filing system to store departmental documents

• Developing a presentation to communicate a new process

The factors that distinguish a small project from a simple project are duration, team size, and degree of formality required to effectively meet stakeholders’ expectations. The project manager must determine what combination of processes and tools fits the needs of the project.

A simple project generally has the following characteristics:

• Is short in duration, typically lasting fewer than 30 days, and usually part-time in effort

• Has three or fewer team members, often handled by a single resource

• Involves a single skill area

• Has a single objective and a solution that is readily achievable

• Has a narrowly defined scope and definition

• Affects a single business unit and has a single decision maker

• Has access to project information and will not require automated solutions

• Uses the project manager as the primary source for leadership and decision making

• Has no political implications with respect to proceeding or not proceeding

• Produces straightforward deliverables with no interdependencies from other skill areas

• Does not require a project budget; costs are handled as part of ongoing operations

What Is Project Management?

“Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to meet project requirements.”3 It includes identifying requirements for the project, defining and planning the necessary work, scheduling the activities to complete the work, monitoring and controlling project activities, communicating project progress among project stakeholders, and finally conducting activities to end the project.

Project management involves coordinating the work of other people. A project manager and a project team are involved in the project. The project manager is the person assigned by the organization to achieve the project objectives. Project manager might not be the person’s formal job title, but for the purpose of this book we will use the term for the person responsible for completing the project. The project team members are the people responsible for performing project work. They complete the project deliverables. They might or might not report directly to the project manager. For small projects team members usually work part-time on the project.

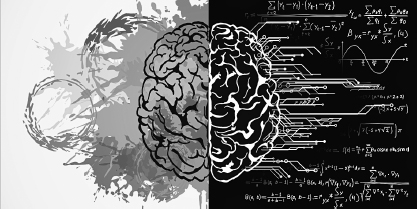

Project management has been called an art and a science. Project management is an art because of the human element. The involvement of interrelationships among diverse groups requires the use of leadership skills, which are applied on the basis of the project situation and are unique to each project. Some of these skills are communicating, negotiating, decision making, and problem solving. The art of project management requires the project manager to gain agreement among technical and business resources, the project team and the customer, and multiple stakeholders. (Stakeholders are people and organizations that are actively involved in the project or whose interests might be positively or negatively affected as a result of project execution or project completion.) To effectively master the art of project management you must develop leadership skills.

Project management is a science because it is based on repeatable processes and techniques. The project manager has an array of tools, templates, and standards to assist with defining and planning a project. In addition, the project manager has an assortment of metrics and status reports for monitoring and controlling a project. To master the science of project management, you must effectively and efficiently apply a system that incorporates the appropriate project management processes and techniques.

Project Management Is Both an Art and a Science

Art: leadership skills

• Establish and maintain vision, strategy, and communications.

• Foster trust and team building.

• Influence, mentor, and monitor team performance.

• Evaluate team and project performance.

Science: the processes necessary to successfully complete a project

The Power of Project Management

A team was assigned to work on a project to revise an existing system. Since the changes were minor and the project was expected to last only five weeks, the project manager was lax in the use of project management processes and tools. Needless to say, the project got into trouble. The project work was not completed on time and the team was discouraged. A new project manager who insisted on the use of project management best practices was assigned. A project charter that gave the team a clear understanding of what was included in the project was developed. The team then worked together to develop the project schedule, which included the name of the resource responsible for completing the work along with the planned start and end dates. The team became reenergized and engaged in completing the project activities.

Project management is art informed by science. “Learning the basic science is a requisite to practicing the art.” 4 Learning the basics of project management—processes, tools, and techniques—is a start and you should not stop there. Incorporating leadership allows you to guide, motivate, and direct a team, make creative decisions, and communicate with all project stakeholders; therefore, increasing your ability to help the organization achieve its business goals.

The Value of Using Project Management on Small Projects

For larger projects, success is measured by product and project quality, timeliness, budget compliance, and degree of satisfaction. Larger projects must balance competing project constraints, including scope, quality, schedule, budget, resources, and risk. However, for small projects, success can be defined as on time, within budget, and meeting the requirements of the project stakeholders. Managers of small projects need to be concerned with meeting this triple constraint, with an understanding that other project constraints may also need to be managed.

The value project management offers is the use of standard processes and tools. Project management is even more valuable when the processes and tools can be tailored to fit the different types and sizes of small projects. By using a methodology, the project manager is more prepared to define and manage the project scope, obtain project requirements, and provide ongoing communication. Stakeholders are engaged early and expectations are known. Add to this the ability to produce realistic estimates and schedules, and to effectively manage issues and risks, and you have a means of managing project constraints. When you can manage project constraints, you improve your chances for project success.

Why Use Project Management?

Project management:

• Helps the organization to meet its business objectives

• Provides processes and tools that create discipline and a means for organizing project data

• Provides a means to define scope and control scope changes

• Defines project roles and responsibilities

• Allows the project manager to manage stakeholder expectations

• Allows the team to focus on priorities

• Addresses the competing constraints of scope, schedule, cost, resources, quality, and risk

Scenario

Kenny has learned that project management is both an art and a science and has concluded that project managers need to constantly balance people and processes.

Finally, using project management on small projects will provide models for future projects. Most small projects tend to be similar in structure or outcome. If a template or model is developed, it can be used for future projects. This saves the project manager time and provides a basis for continuous process improvement.