Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Strategies for Project Sponsorship

Vicki James (Author) | Ron Rosenhead (Author) | Peter Taylor (Author)

Publication date: 05/01/2013

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Vicki James has spent more than a decade in the public sector successfully delivering projects to support governmental operations. She is president of the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) Seattle chapter and contributes to professional project management publications. She holds certifications as both a Project Management Professional (PMP) and a Business Analysis Professional (CBAP).

Ron Rosenhead has over 25 years as a trainer and consultant, most recently specializing in helping organizations ensure project success. He has personally trained and coached over 10,000 individuals in project management in both the private and public sectors. He is a professional speaker, a regular blogger, and author of Deliver the Project.

Peter Taylor has been involved in project management for more than 27 years, heading a project management office (PMO) for the last eight years. He is now a PMO coach and speaks internationally on project management topics. He is the author of The Lazy Project Manager, The Lazy Winner, The Lazy Project Manager and the Project from Hell, Leading Successful PMOs, and Project Branding.

CHAPTER 1

Preparing to Work with Your Sponsor

How many project managers get to choose the projects they manage? Not many. The project allocation process in most companies just doesn’t work that way, does it?

Now, how many project managers get to choose the project sponsors they work with? Probably none. Again, it just doesn’t work that way in most, perhaps any, organizations. You won’t get the opportunity to ask a sponsor for her résumé and put her through a formal interview process—nice as it would be to say, “I’m sorry, but I just don’t think that this is the job for you right now,” if she isn’t a great fit for the position.

But perhaps you can, through your experience and your relationships with executive management, request a particular person you know you can work effectively with to partner with you once again on your next project. You also can try to educate the decision-makers about how to select the best possible project sponsor. You may be able to influence the way the organization selects and assigns sponsors by sharing some high-level definitions and expectations of the sponsor role based on this book and other best practices. (Chapter 6 provides more information on these concepts.)

Even if you don’t have the perfect sponsor, you can prepare to work with the one you have by knowing what you’re in for and making sure you get off to a good start.

WHO SHOULD SPONSOR YOUR PROJECT?

![]()

Make a judgment call on what competencies this particular project requires. Is the project simple or complex? Should you ask to be assigned the sponsor you want, or can you risk working with a new (perhaps good, perhaps not) sponsor on this project? There are probably several people within the organization who could be good sponsors for your project. The following criteria will help you work with executive management to appoint the person most likely to guide the project to success:

• Who has the greatest interest in the outcomes of the project?

• Who has the greatest influence with the high-level stakeholders of the project?

• Does this person have proven experience in sponsoring projects?

• Does this person have the capacity to be an effective collaborator and leader for the project manager and project team?

• Does this person have education and experience in project management best practices?

• Does this person trust those around him to act in the best interest of the project?

If the same person is named in your responses to questions 1 and 2, and you can answer yes to the remaining questions, you have your sponsor.

If the person named in your answers to 1 and 2 is not capable of sponsoring the project, look for a trusted delegate to assign as sponsor, or negotiate and document the roles of the delegate (the more capable person) and the sponsor (the more influential person).

If you name different people when answering questions 1 and 2, select the more appropriate sponsor based on the answers to the remaining questions.

Remember that lacking competencies can be mitigated through sponsor education. Help the sponsor understand what is in it for her and how these competencies can maximize the chance for project success.

ASSESSING YOUR SPONSOR

![]()

Let’s say you’ve been assigned a project and a sponsor, and that is that. You’re left to deal with what you’ve been given. It is said that you cannot manage what you don’t measure, and that is as true for project sponsors as it is for anything. So let’s start there: how can you assess your project sponsor? In this book, we give you a variety of checklists to help you to understand your project sponsor (see later chapters and appendixes). Below, we detail other tools you as the project manager can use to better understand your sponsor and then to adapt your communication style and project approach to make the most of her skills.

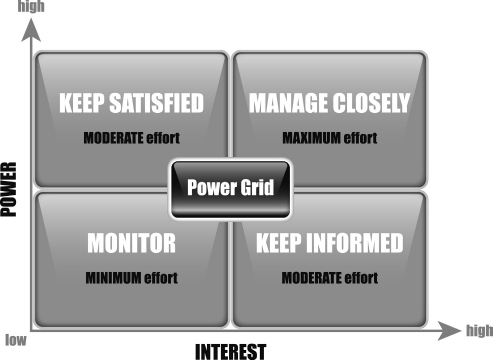

THE POWER GRID

You can use the power grid shown in Figure 1-1 to assess your newly assigned sponsor—specifically her interest in your project (from high to low) and her actual power in your organization (also from high to low). This may well be challenging to determine early on—especially if you have never worked with this sponsor beforehand—however you can update your assessment as you personally get to know your sponsor better and you build a relationship.

FIGURE 1-1: Power Grid for Assessing Sponsors

![]()

Initially, though, you can use your past observations of this sponsor (if you have any), current discussions (that you are undertaking with the sponsor—you are on that learning curve already), and peer responses (you can ask your colleague project managers about the sponsor if they have worked with her on past projects).

The power grid suggests general courses of action you can try to manage your relationship with any sponsor.

If your project sponsor falls into the “low interest, low power” quadrant, you really have a problem. It is unlikely that this sponsor will ever support your project management endeavors; even if she could be persuaded to, her influence is so weak that her cooperation is not worth pursuing.

On the other hand, a “high interest, high power” sponsor can be very useful indeed. However, she will also have to be managed carefully, because her high interest in the project could lead to micromanagement and long, overly detailed update meetings. This is not something that a project manager wishes to encourage.

Let’s take a closer look at specific strategies for managing to the power grid:

• Manage closely. This sponsor is very interested in what is going on with your project and has great influence over it. As such, she should always have the most current information on project progress and challenges and should be able to provide the helicopter view—i.e., whether it sits with the overall strategy of what is going on. Reporting to this sponsor may mean daily emails and weekly meetings. The danger of not “managing closely” is that trust will not be optimized, thereby creating a risk for micromanagement from the sponsor.

• Keep satisfied. Find out what your project sponsor expects and meet those needs. The goal is to provide enough information that she feels informed but not so much that she feels burdened. Make requests of her only when there are no other channels, and come armed with a completed analysis of options already considered.

• Keep informed. Interested sponsors require information, so make sure you have processes in place so they know about progress and challenges and how to easily gain further information of they feel that they need it. This includes weekly status updates and regularly scheduled meetings.

• Monitor. Ask questions of your sponsor to ensure she feels informed, knowledgeable, and included in the project. This sponsor may not be keeping up with the project progress and status, so your challenge is to make sure that she both understands and appropriately acts on project successes and challenges when needed.

TYPES OF POWER

All project stakeholders—indeed, anyone in an organization—can hold one or more types of power. Which of the following does your sponsor have? Which do you have?

• Legitimate: power endowed by a formal title or position (authority)

• Reward: power held by those who are able to impose positive consequences (carrot)

• Coercive: power held by those who can impose negative consequences (stick)

• Financial: power held by those who control the budget (money)

• Bureaucratic: power held by those with knowledge of the system (intelligence)

• Referent: power endowed by association with someone else’s power (network)

• Technical: power held by those who have technical knowledge relating to the project (skill)

• Charismatic: power granted through personality alone (character).

You and your sponsor can work together to use her (and your) power how and when you need to. But use it sparingly and use it wisely.

Let’s take a closer look at these types of power and how they can be used:

• Legitimate power. Regardless of the type of organization—hierarchical or matrix—in which you work, the more senior a person is, the greater the opportunity to assert authority and cause things to happen. This power should be used sparingly.

• Reward power. Commonly used to engage resources and stakeholders, this power may be used at the start of a project as part of a marketing activity or later in the project to focus efforts and meet a deliverable milestone. Rewards can be offered directly from the sponsor or through you, the project manager, as fits the situation. Rewards can also be offered for good work or given as surprise “thank-yous” to good contributors.

• Coercive power. Perhaps the least used type, this will likely achieve what you and your sponsor want but not gain ongoing cooperation. Often it can be better to offer the “carrot” alongside the “stick.”

• Financial power. In many cases this type of power allows application of the “reward” power but can lead to a declaration that “this is my budget (and my project) and I will apply it as I see fit”—a kind of “take it or leave it” negotiation position.

• Bureaucratic power. By understanding how things work inside your organization and aligning requirements with mandated processes (such as matters of compliance and regulatory authority), you can use this type of power to make and enforce decisions.

• Referent power. This is the “my dad is bigger than your dad” style of argument. The stronger a person’s network, the greater the inferred authority. This authority comes not from the power and influence of an individual but from that of associates.

• Technical power. A key role of any successful project manager is to understand the critical details. Those who possess this knowledge have the advantage.

• Charismatic power. Both the project sponsor and the project manager can gain a lot of favors through being positive, engaging, and likeable. If you are fun to work with, viewed as successful, and considered influential, this power will get people on your side.

You may be wondering how you and your sponsor can work together to leverage the types of power you both possess. You will find the answers in just about any cop show, but “good cop, bad cop” is just one example: the bad cop uses coercive power to try to scare the criminal into submission while the good cop uses reward and charisma to show what good can come of a full confession.

You will find that you may have any or many of these types of power at your disposal given the situation. Project sponsors and project managers often fall into particular types of power according to their position in the organization:

• Project sponsor

Legitimate

Legitimate

Coercive

Coercive

Financial

Financial

Charismatic

Charismatic

• Project manager

Legitimate

Legitimate

Reward

Reward

Technical

Technical

Referent

Referent

Charismatic

Charismatic

A project sponsor may use legitimate and coercive power to get team members to the table, but the project manager will get a better result by combining those powers with technical and charismatic power to earn their trust and desired participation. On the other hand, you may have great technical power but need to call upon your project sponsor with bureaucratic power to help mitigate a risk to the project from another division. Work to enhance the powers that come naturally to you and the situation while learning to leverage the power of your project sponsor to complement it. Together, you can be the perfect partnership or the dynamic duo.

INTERVIEWING THE SPONSOR

![]()

More often than not, the project sponsor has been chosen by the business well before you have even been selected as the project manager. However, if the company has a strong project management culture, this idea is entirely plausible. If, of course, your company does not have a strong project management culture, the interviewing of a possible sponsor for your project is something for you to work on!

But let’s just assume for one magical moment that you could interview her; this could be fun. Suspend your disbelief and go with it. What if a prospective sponsor answered your questions as follows?

Q: Tell me why you think you are the right person for this job.

A: Well, what skills are you looking for in a good project sponsor?

Q: What strengths will you bring to the role?

A: What are the strengths that would make your life as a project manager that much easier?

Q: What are your weak points, and what actions will you take to address these issues?

A: What weaknesses are you looking to avoid at all costs?

To this, you might reply, “You know, I’m sorry, but based on your experience, I think it is better if I look elsewhere for my project sponsor this time around. Thank you for your interest.” (Of course, you can only dream of saying this!)

You may actually be able to get answers to a few of these questions by indicating that you want to leverage your strengths and weaknesses against hers. You also should be prepared to answer these questions yourself so that you can look at your own strengths and weaknesses.

This chapter is titled “preparing to work with your sponsor.” If you are indeed to prepare, then you need data. You can assess the sponsor using the tools mentioned and others presented further on in the book. However, wouldn’t it be useful to you, the project manager, to understand where the sponsor has strengths and development needs?

In the box below, we present a variety of candidates put forward for a sponsor role. You may never get the opportunity to formally interview your sponsor. However, you may need to understand your sponsor just that little bit more, and we believe the ideas below will help. Don’t forget: an interview can reveal development needs—something you can help the sponsor with!

INTERVIEWING SPONSOR CANDIDATES

Imagine that you have the opportunity to interview four potential project sponsors for your project. Once you have heard from all four, you can elect to take further action to help you decide, or you can make an immediate decision.

Candidate 1

I have been working at this company for five years and have progressed to the executive level in the last year. I haven’t as yet sponsored a project, but I am keen to get the first one under my belt. Your project seems pretty interesting and quite important to the company, and it would be great to work with you on this.

I have a reasonable amount of time to spend on it, apart from a three-week vacation the month after next, but aside from that, I am there for you as you need me.

I’m not too fond of long meetings, so I would suggest we catch up by phone every week or so—or perhaps you would suggest something different; you are the expert, after all.

Candidate 2

You know me pretty well, since we worked together on Project Phoenix a year or so ago. I know it was a bit of a rough ride, but we mostly got there in the end. I do have experience in project sponsorship, I understand this whole project-based activity thing, and I am right behind this particular initiative. In fact, I was the main voice on the approval board to get it up and running.

Since we last worked together, I sponsored the new expense management project, and that went live only last month.

It seems like it makes a lot of sense for us to join forces once again and get this one delivered for the business.

Candidate 3

I’m glad I could make this meeting—I just love working with you project managers, and this would be my fourth project sponsor role right now. This is a key role, as you know, and I want to bring my experience and authority to bear in order for you to do your bit successfully. Sponsoring a project is all about getting people pointing in the right direction and providing the occasional kick to anyone who gets in your way. You just let me know who, and I’ll sort it out for you.

Candidate 4

[Candidate 4 apologizes for being unable to make the interview, as he is responding to an urgent work situation. He did say that he has past experience as a sponsor and would be eager to support this project when it starts.]

Action

You now have to decide what to do next. Can you decide which sponsor you want to work with now, or is there more that you need to know?

• Write down your plan of action.

• Will you reject any sponsor candidate now?

• What steps will you take to reach a point of decision?

• Whom do you favor at this point in time?

Here is one possible way of looking at the candidates.

Let’s start with candidate 4. Even though he could not make the interview, he does have experience and appears to be focused on urgent matters. You may well decide that he is worth a little more effort and reach out to his peers for more information. What specific experience does he have, how did his projects progress, and what do the project managers he’s worked with have to say about him? As for the “urgent work situation”—was it really urgent, or was it just an excuse? If you like what your research reveals, then you may have a good candidate to consider; if not, then perhaps it’s best to reject him.

Candidate 1 seems enthusiastic, but on the downside, she has no experience as a sponsor and, while she is at the executive level now, she’s pretty new and perhaps might not have the necessary influence yet. She has preferences regarding communication but also seems open to your guidance.

Candidate 2 has a track record, and you have personal experience working with her. It was not a particularly positive experience, but maybe “better the devil you know” applies. At the very least, you should talk to the project manager for the expense system project and see if she exhibited the same behavior that made working with her difficult, or perhaps she has learned how to be a better project sponsor in the interim. On the positive side, she seems to believe in this new project, as she was a strong supporter in the approval phase.

Candidate 3 appears to collect projects as a hobby, but does he really understand the role of sponsor, and can he really sponsor so many projects at one time? What if there are conflicts between the projects—how will he manage this? You might look into the timing of his other projects and see if some are coming to an end any time soon. You would need this sponsor to agree not to take any more projects on while yours is running.

You may want to assess the past performance of all of the candidates you put on your short list using the checklist of sponsor responsibilities introduced in Chapter 2, based on personal observation, postproject reviews, and information from peers. And remember, you will also gain valuable insight by asking them about their hopes for and fears about the project.

KICKING OFF YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE SPONSOR

![]()

It has often been said that it is people who deliver projects. We appreciate the need for really strong processes to ensure effective delivery. However, we also know that for projects to be delivered, we must work with and through other people. This means helping to develop rapport with others, including the project sponsor, the project team, senior-level people in the organization, and all manner of project stakeholders. By rapport, we mean the feeling that “occurs when two or more people feel that they are in sync or on the same wavelength because they feel similar or relate well to each other.”1

MAKING THE MOST OF THE FIRST MEETING

One of the authors was in training with Stuart. Stuart worked for the company and was to become the company project management expert and one-man PMO. He said that project managers needed a key skill—the ability to “raise their head above the parapet.” He meant that sometimes project managers need to go outside their comfort zones. They need to ask awkward questions and deal with completely arbitrary delivery dates (set in offices that are often a long way from the project), among many other difficult duties. They need to use their professional judgment to resolve a host of potential problems. One of these problems can be headed off ahead of time: lack of knowledge and understanding of the sponsor’s needs, style, ambitions, and objectives.

Knowledge is power. Why enter into a working relationship with your new project sponsor in a state of ignorance? Planning and preparation before your first meeting with the sponsor goes a long way to making the meeting a success. By success, we mean not just that you get along and enjoy a civilized chat about the project, but rather that you leave the meeting with the information you need to work effectively with the sponsor in the coming months.

But how can you prepare for such a meeting? Assuming that the sponsor is new to you, there are a number of things that you can do before your first meeting. Doing nothing beforehand makes no sense at all.

Start by considering her project sponsorship experience. Now, this does not mean that you should conduct an investigation into your new sponsor—don’t hire a private eye just yet! It just means that you can subtly and quietly gather some intelligence from

• Project manager peers (who may have worked with her as a sponsor beforehand)

• Other project sponsors (with whom you have worked and who may know this person)

• Executive managers (with whom you have a good working relationship).

Ask about the successes and the challenges that the sponsor has faced, how she responded to any problems, and how she supported project manager(s) she has worked with.

Be sure to also look into any project-based experience she may have. Maybe you will strike gold and connect with a project sponsor who has a project management background. This does not necessarily mean that she will be a good project sponsor, but it will mean that she appreciates the “thrill” of the project world and the special challenges that can be thrown the way of a project manager.

Finally, try to get a view of her management style and the authority that she carries within the organization. This will help you assess her as a sponsor and determine the particular ways in which she can be helpful to you.

Now that you know something about your sponsor, what should you expect and how should you behave in that critical first face-to-face meeting? What is important to cover now, and what can wait until later on?

In this first meeting, you have two major objectives:

• Develop a relationship and rapport with your project sponsor that sets the stage for successful collaboration throughout the project.

• Begin capturing important information that will be used to formally begin the project (i.e., to develop the project charter or other initiation document).

When preparing for the first meeting with your sponsor, you need to understand that some sponsors will have a very fixed vision for the project and will tell you, and the rest of the project team, exactly what they want, when they want it, and what will happen if they don’t get what they want. Be cautious with these sponsors; their strength of purpose and character may challenge your interviewing skills. Even if your sponsor makes things difficult, persevere until you have agreed on a purpose, which you need to run the project, and work closely with him. Use your newness to the project and ignorance to your advantage. Ask the sponsor to help you understand the drivers for the project and what benefit she expects to achieve.

Other project sponsors may have a vision that appears to be an undefined conceptual possibility, developed, perhaps, with a small dose of delusion. Again, you have to apply control and discipline to reach the level of understanding and detail that you need in order to be an effective manager of the project.

The initial meeting is where you will set the tone for the relationship with your project sponsor for the rest of the project. This is your opportunity to impress her with your professionalism and expertise. We will walk you through an agenda for this initial meeting that will make you look good and give your project sponsor confidence in your abilities.

THE AGENDA

Likely attendees include the project manager, project sponsor, business owner/customer, lead business analyst, and others as appropriate. Topics you may want to cover include the following:

• Business objective

• Anticipated impact of project deliverables

• Quality expectations

• Risks

• Business drivers

• Stakeholders

• Constraints (budget, dates, policy, other)

• Decision-making

• Supporting the team

• Communications planning

• Mutual understanding of the assumptions that have been made in developing the business case and expected outcomes.

Peter discusses the first seven bullets in his book The Lazy Project Manager2; here, we will focus on relationship building.

Admittedly, this suggested agenda is quite full—you may need to have a number of meetings to cover all of the topics, or you can explore other ways to elicit information from, or share information with, your sponsor.

ASKING THE QUESTIONS YOU NEED TO ASK

Going back to the second primary objective of your first meeting with the sponsor—beginning to capture important information that will be used to formally begin the project—consider the topics listed above.

Remember, first impressions really count, so be sure to prepare well. If you conduct yourself in a professional, confident manner in your first meeting with your sponsor, you will not only make a positive impression by demonstrating your capability, but you will also provide a valuable service to the sponsor by bringing your expertise and project experience to the forefront of the project.

One tip here: you are only in the information-gathering phase right now, and while you do want to manage the project with a firm hand from day one, you have to be sensitive at this first meeting. We advise being a little gentle to begin with, at least until you understand what type of sponsor you are dealing with. Now is the time to just observe the sponsor and determine what style of communication and kind of relationship she expects from you. You can put a firm grip in place and negotiate hard later on. Right now, just learn and inwardly digest what you are told.

DETERMINING WHAT’S IN IT FOR THE SPONSOR

You need to understand, if you don’t already, what is in it for your sponsor—what her previous experience as a sponsor has been like, both in terms of her knowledge about being a sponsor and her real project experience (i.e., was a previous project a nightmare project?). Even if she has never sponsored before, she will, no doubt, have an opinion of sponsoring based upon stories she’s heard about past projects and from other executives. Determine her willingness to learn more about project sponsorship and the best way to help coach her (e.g., reading this book, receiving just-in-time feedback, or attending training).

Manage your sponsor well, and he will be your ally in the coming weeks and months.

OPEN DISCUSSION WORKS

Feel free to start the conversation at the first meeting in a simple way, with an open question—for example, “Tell me about the project.” Active listening is an underutilized skill in communication. Use it now. There is enormous value in asking your sponsor to answer just two (apparently) simple questions:

• What are your hopes for the project?

• What are your fears about the project?

You will gain a lot of insight into how the sponsor feels about the project and the challenges you may have to plan for in the coming weeks and months by asking these questions. The answers will also help you capture data for project initiation without getting “technical” right away.

Open questions have the following characteristics:

• They ask the respondent to think and reflect.

• They are designed to elicit the respondent’s opinions and feelings.

• They hand control of the conversation to the respondent.

• They are likely to receive long answers (this is true of any question, but open questions deliberately seek longer answers).

ASKING ABOUT THE SPONSOR’S EXPECTATIONS

You have already talked with others about your sponsor’s experience and approach, while avoiding taking at face value any secondhand statements or rumors about her views and expectations. To find out what she really wants and expects, you have to speak with her directly and take only her word regarding her expectations. It may well be possible that the sponsor does not yet know what she expects. Perhaps this is her first time as a project sponsor and the role is as new to her as she is to you. If that is the case, you need to help her and guide her in his responsibilities.

Once you have a broad understanding of the sponsor’s feelings about this particular project and an idea of what she expects from you and the project, you can follow up with other questions to reach a suitable level of confidence in your understanding of the key topics.

TIME COMMITMENT

Obviously, the project sponsor must devote time to the project if it is to have the greatest chance of success. Have an open conversation about the time commitment so you can reach agreement about it before the sponsor’s project responsibilities begin. The amount of time the sponsor will need to spend will vary project by project, depending on size, risk, and complexity. This could be anywhere from one hour a day for a high-risk, highly complex project to 30 minutes once per month for simple projects. Your project sponsor should be ready to commit to a minimum of 30 minutes per month to discuss project status.

This is a good time to make sure the sponsor understands that there may be periods when she will need to spend more time than usual on the project. Let her know that you are conscious her time and that you will not be asking for her attention frivolously.

Now also is the time to find out who the trusted delegates of the project sponsor are and their level of authority. Schedule the 30-minutes-a-month minimum even if the sponsor fully delegates all aspects of the project. The only way to be sure that the project sponsor is fully aware of status and issues is to meet with her personally. Include sponsor delegates in the meeting to keep communications open and maintain trust.

DECISION-MAKING

Any project will frequently require that your project sponsor make decisions. A delay in a decision can have a significant impact on the project schedule. Talk about this with your project sponsor and help her understand how crucial timely decisions are in keeping a project on track. Work to get agreement that the sponsor will make needed decisions within 24 hours. Failing to make a decision in that time frame may result in a project change request to adjust the schedule for the delay.

Find out what your sponsor will generally want from you and the project team to keep her commitment on decision-making. Will she want full details and copies of all of the relevant documents? Perhaps she will simply want a summary of the issue with a recommended action, or a list of options that the team has already explored from which she will choose. If you know her general preference, you can proactively prepare and give her what she needs. Keep in mind that she may ask for different information or recommendations for any given risk.

Having this discussion early to set guidelines and establish a common understanding of the sponsor’s information needs will go a long way toward helping her provide decision support throughout the project. We have noticed that communication within projects and project management in particular tends to be poor. It takes time, planning, and a commitment by the project manager and team. Only then will trends in reporting of communications improve (and improve they must!).

TEAM SUPPORT

Your project sponsor may not be aware of how valuable her public and private support of the team can be for the project. Staffers who understand how they are contributing to the greater good of the organization will perform better and have better morale. Nothing sets the tone for this more than a project sponsor who takes an active interest in the team. Taking an active interest does not mean that team members should begin going to the project sponsor instead of the project manager with concerns, but only that each contribution is valued by the sponsor and therefore the organization.

Let your sponsor know that simple acts can go a long way in supporting the team. She can

• Speak at the project kickoff about the project, its purpose, what changes she anticipates, and her appreciation of those contributing to it.

• Meet team members, ask what they do on the project, and remember them.

• Acknowledge team members when she sees them at the water cooler.

• Ask how the project is going and if they have any concerns. (Concerns need to be resolved through the project manager, but that does not mean the sponsor cannot care about them.)

• Send a personal note or email of appreciation when she hears of good work or extra effort from team members.

• Support efforts to identify project stakeholders and their management. (This is particularly important for the “political” stakeholders the project manager may not be aware of.)

• Attend a milestone or retrospective meeting to thank the team in person (bringing goodies doesn’t hurt).

• Always acknowledge the team and its efforts when speaking to others about the project.

COMMUNICATIONS PLANNING

Being the best project manager for your sponsor will take a lot of planning, particularly communications planning. Some 80 to 90 percent of what we do as project managers is communicate. Planning ahead about how you will communicate will take much of the work out of the actual communications throughout the project.

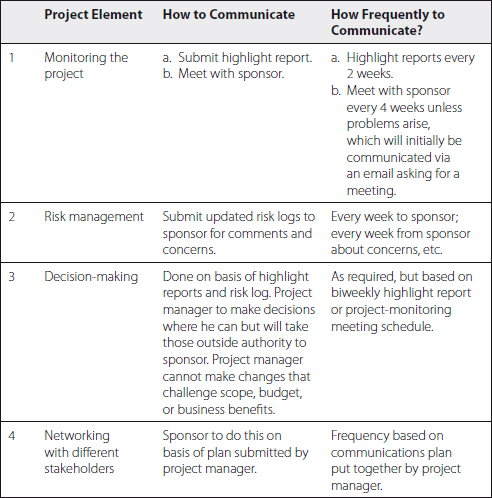

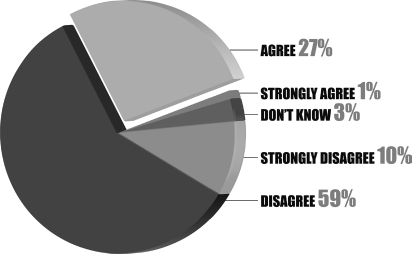

Let’s take a look at the results of a ten-year survey conducted by the project management training and consultancy company Project Agency.3 Almost 1,500 people were asked whether they agreed that the following statement regarding communication in their projects was true: “Communication is such that people are always aware of changing priorities.” The results are shown in Figure 1-2; more data are available in Appendix A.

The survey participants clearly suggested that communication within their projects is poor. Corroborating this, we have heard some very negative comments about communication from people who have attended our project management courses. Typically, they say that communication in projects reflects communication in the business—it’s all generally poor.

FIGURE 1-2: Effectiveness of Communication

![]()

But a project manager who is striving to be the best does not just accept weak communication within projects. It’s essential to think about, trial, and put into play key plans for communication. As you develop plans for communicating with your sponsor, think about what you’re trying to achieve:

• Get a decision on something

• Seek advice from someone who has a different perspective

• Talk about a problem and make a recommendation or suggestion

• Go through the agreed-upon reporting process

• Suggest that she open a door for you: “I really need to see someone in Human Resources—whom do you suggest, and how?”

You will have to develop a clearly defined plan for communicating in any situation that’s likely to arise.

One of the many benefits of planning communication is preventing the parties from falling into the trap of resorting to type. For example, let’s say you prefer to talk face-to-face with people and do so as much as possible. Under pressure, you may feel as if a face-to-face conversation is the best or only way to deal with a concern, but face-to-face communication is not always feasible or the best approach in every case. Developing a specific communication plan that states how you’ll communicate about particular project elements will help you avoid resorting to your preferred method if it’s not the most effective one for the situation.

How can you get started devising a communication plan? We have often used an exercise with teams that will work equally well with your project sponsor. It is a simple round-robin discussion where each person answers the following questions:

• What is your preferred method of communication?

• What is the best way to alert you of something urgent?

• How will I know when you are stressed?

• What is the best thing I can do when you are stressed?

• What else should I know about you?

The answers are recorded, shared, and kept in a common place where they can easily be referenced. If others who are familiar with your sponsor are in the room when you’re asking her these questions, ask them for their input regarding her communication style. This often brings out feedback that may surprise the sponsor.

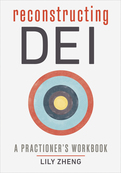

After you’ve gathered the above information, work to get agreement on communication guidelines before the project gets underway. Getting basic information on preferences should be part of your initial discussions with your project sponsor and key stakeholders. Start a communications matrix, like the sample plan in Figure 1-3, that describes the project elements about which you will need to communicate, how you’ll communicate about each one, and how frequent those communications will be. Then walk through the plan with your sponsor to elicit his feedback and make adjustments as needed.

Keep the following in mind regarding communicating with your sponsor:

• You are responsible for submitting a communications plan.

• Think of new, efficient ways that you can share information with your sponsor. Perhaps you can text or instant-message urgent information, share status updates on an organization bulletin board, or create a group page on a common social media site such as LinkedIn or Facebook.

FIGURE 1-3: Sample Communications Plan

![]()

• Once you know what methods your sponsor prefers, use those approaches, but supplement them with other methods as needed.

• Use multiple channels—for example, email as well as in-person meetings—for communicating with your sponsor.

• If you think you are over-communicating, ask your sponsor. She may begin to disregard your messages if she thinks you are overdoing it.

• If your sponsor simply does not want to engage in any way, this is a risk to the project. Put the problem in your risk log and let your sponsor know! This is tough but very necessary for your project and your sanity. It may open the door to talking with the sponsor about ways he can meet the project’s needs, such as through delegation.

• You will need to invest more time in communicating with inexperienced sponsors.

• If you are working with a bureaucratic sponsor, she will expect (indeed demand) that you complete the right project management paperwork at the right time and in the prescribed manner. Any delay in supplying this will possibly delay the project. Your communications to the sponsor are through the project documentation and need to be right. Work to her strengths!

• If you’re working with a detail-oriented sponsor, be sure to supply the type of information she requires. Keep backup information in your hip pocket, so to speak, when meeting with her.

• Remember, your goal is to be the best project manager for your sponsor. Consider leadership guru John Kotter’s advice: “Good communication does not mean that you have to speak in perfectly formed sentences and paragraphs. It isn’t about slickness. Simple and clear go a long way.”4

NOTES

1 Wikipedia, “Rapport,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapport.

2 Peter Taylor, The Lazy Project Manager (Oxford: Infinite Ideas, 2009). This book illustrates how people can apply the simple techniques of “lazy” project management to their own activities in order to work more effectively and consequently improve work–life balance. The approach of “productive laziness” builds on the Pareto principle, which states that for many phenomena, 80 percent of consequences stem from 20 percent of the causes. To put it simply, only 20 percent of the things people do during their working days really matter.

3 Project Agency is a London-based project management consultancy led by Ron Rosenhead, a coauthor of this book. (More information is available at www.projectagency.co.uk.)

4 Harvard Business School Bulletin [online] (February 2001), http://www.alumni.hbs.edu/bulletin/2001/february/kotter.html.