Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Business of Building a Better World

The Leadership Revolution That Is Changing Everything

David Cooperrider (Edited by) | Audrey Selian (Edited by) | Jesper Brodin (Foreword by) | Halla Tómasdóttir (Foreword by) | Natalie Hoyt (Narrated by)

Publication date: 12/14/2021

Through the exploration of robust cases and stories packed with deep insight and vital science, this extraordinary collection explores how we can adapt our notions of value, markets, and models of cooperation and collective action to create a world where economies and businesses excel, all people thrive, and nature flourishes.

In part I, The Business of Business Is Betterment, the contributors show how enterprises today are further developing-and even taking a quantum leap beyond-the multistakeholder logic of shared value creation. Part II, Net Positive = Innovation's New Frontier, is focused on what companies can and are doing to move away from doing no harm to playing an active role in solving environmental, social, and economic problems. The final section, Ultimate Advantage: A Leadership Revolution That Is Changing Everything, looks at new leadership paradigms-characterized by unexpected qualities like virtue, love, compassion, and connection-that are crucial to creating engaged, empowered, innovative, and out-performing enterprises.

This book is designed to galvanize change and unite a global community of inquiry and action. It establishes the conceptual cornerstones for a new kind of business practice that will lead the way to an equitable, sustainable, and flourishing future.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Through the exploration of robust cases and stories packed with deep insight and vital science, this extraordinary collection explores how we can adapt our notions of value, markets, and models of cooperation and collective action to create a world where economies and businesses excel, all people thrive, and nature flourishes.

In part I, The Business of Business Is Betterment, the contributors show how enterprises today are further developing-and even taking a quantum leap beyond-the multistakeholder logic of shared value creation. Part II, Net Positive = Innovation's New Frontier, is focused on what companies can and are doing to move away from doing no harm to playing an active role in solving environmental, social, and economic problems. The final section, Ultimate Advantage: A Leadership Revolution That Is Changing Everything, looks at new leadership paradigms-characterized by unexpected qualities like virtue, love, compassion, and connection-that are crucial to creating engaged, empowered, innovative, and out-performing enterprises.

This book is designed to galvanize change and unite a global community of inquiry and action. It establishes the conceptual cornerstones for a new kind of business practice that will lead the way to an equitable, sustainable, and flourishing future.

Preface

-Introduction - A Moonshot Moment for Business and the Great Economic Opportunities of Our Time by David Cooperrider and Audrey Selian

-PART I: The Business of Business is Betterment

-Chapter 1- The Trillion Dollar Shift: Business for Good is Good Business by Marga Hoek

-Chapter 2 Taking Leadership to a New Place: Outside-the-Building Thinking to Improve the World by Rosabeth Moss Kanter

-Chapter 3 A Decade that Transformed the Role of Business in Society - A Snapshot by Mark Kramer

-Chapter 4 Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism by John Elkington, Richard Roberts and Louise Kjellerup Roper

-Chapter 5 Contemplating a Moonshot? Ask Yourself These Three Questions: Why This? Why Now? Why Me? by Naveen Jain, with John Schroeter

-PART II: Net Positive = Innovation's New Frontier

-Chapter 6 Net Positive Business and the Elephants in the Room by Paul Polman and Andrew Winston

-Chapter 7 Accountability for All: There is No Stakeholder Capitalism Without Stakeholder Governance by Bart Houlahan and Andrew Kassoy

-Chapter 8 The Business of Business is the Future by Raj Sisodia

-Chapter 9 Stakeholder Capitalism: Three Generations, One Voice by R. Edward Freeman, Joey Burton, Ben Freeman

-Chapter 10 Transforming Business, Transforming Value by Gillian M. Marcelle and Jed Emerson

-Chapter 11 The Problem with Removing Humanity from Business Models by Roger L. Martin

-PART III: The Ultimate Advantage: A Leadership Revolution That is Changing Everything

-Chapter 12 Business as an Agent of World Benefit: The Role of Virtuousness by Kim Cameron

-Chapter 13 Love: The Core Leadership Value and Organizing Principle for Business and Society by Michele Hunt

-Chapter 14 The Role of Consciousness in Accelerating Business as an Agent of World Benefit by Chris Laszlo and Ignacio Pavez

-Chapter 15 Innovating to Flourish: Towards a Theory of Organizing for Positive Impact by Udayan Dhar and Ronald Fry

-Chapter 16 Towards Reinvention of Your Theory of the Business: Five Principles for Thriving in the Disrupted World by Nadya Zhexembayeva and David L. Cooperrider

Acknowledgements

About the Authors

1

Introduction

A Moonshot Moment for Business and the Great Economic Opportunities of Our Time

DAVID COOPERRIDER AND AUDREY SELIAN

ONE OF HUMANITY’S GREATEST GIFTS is that in times of profound shock and disruption, new perspectives are forged. Such moments tend to be historical ones—moments when new possibilities for humanity can be established and new eras born. Could it be that we are standing at the threshold of the next episode in business history?

The quest in this book is ultimately to explore the profound new enterprise logic propelling the “business of building a better world”—ways that the field of business is increasingly becoming an agent of change and a partnership power for building a better world—together with all of this serving as a catalyst for the “betterment of your business.” Moreover, this includes all the new ways that The Business of Building a Better World can lead inside the enterprise to bold new waves of innovation, business outperformance, and what we call full-spectrum flourishing. Flourishing enterprise is something every industry leader increasingly wants. Flourishing enterprise, as we shall discover, is about people being inspired every day and bringing their whole and best selves into their businesses; it’s about innovation arising from everywhere; and most important, it is about realizing sustainable value with all stakeholders. These include customers, communities, shareholders, and societies, all coexisting ultimately within a thriving, not dying, biosphere.

SOMETHING REMARKABLE IS UNDERWAY

The relationship of business and society—and the unprecedented search for mutual advances between industry and the world’s profound upheavals—has become one of the decisive quests of the twenty-first century. As we stand now in what scientists are calling the “decade of determination,” the stakes could not be higher for humanity and planet Earth. Like dials on a seismograph, we have stood stunned as the decade of the 2020s has arrived with unprecedented disruptive preludes: megafires in January; a global pandemic in March; an economic crash in April with bankruptcies putting millions out of work; and protests across the planet for racial justice and inclusive systemic change in June and beyond. Only just a few months earlier, we listened to the rising voices of millions of millennials and Gen-Z young leaders, including Time magazine’s Person of the Year Greta Thunberg and over 7 million strikers from six continents. For them, the entire era of climate gradualism “is over.” As our youth stepped onto podiums in a series of high-level venues with world leaders—from the Assembly Hall of the United Nations to Davos in Switzerland, where thousands of business leaders gathered at the World Economic Forum—young people cried out for a war-time mobilization commensurate with the state of “climate emergency,” urging everyone to embrace the empirical evidence, pointing to articles such as the one in Bioscience signed by tens of thousands of scientists stating: “We’re asking for a transformative change for humanity” (Ripple et al. 2020).

To be sure, these voices are scarcely alone. Many executives too are seeing a world where society is being irreversibly mobilized. BlackRock’s CEO Larry Fink, for example, declared in front of Wall Street that climate action has now put us “on the edge of a fundamental reshaping of finance” (Fink 2021). These are not the words of a scientist or activist but the conclusions of the head of the largest investment company in the world, managing over $7 trillion in assets. Perhaps most important, however, is that trajectories like this are advancing significantly beyond words on a piece of paper. The past decade saw, for example, sustainably directed assets under management triple to more than $40 trillion globally so that they now represent $1 of every $4 invested (Lang 2020).

Indeed, positive disruptions across the business landscape are booming, and in many cases, they are propelling companies to outperform—not incrementally but significantly. Companies such as Toyota are, right now, building net-positive cities that give back more clean energy to the world than they use while leveraging artificial intelligence and biotechnologies to reinvent and individualize medicine, turn waste into wealth, propel zero-emissions mobility, and even purify the air that people breathe. Corporations such as Unilever, Danone, Westpac, Grameen Bank, Nedbank, and Greystone Bakeries have turned theory into reality with base-of-the pyramid innovation and social business strategies demonstrating how the enterprising spirit can eradicate human poverty and inequality through inclusive prosperity, profit, and dignified work. Thousands of entrepreneurial initiatives have been launched, as smaller companies like Frontier Markets in Rajasthan, Aakar Innovations in Mumbai, or Springhealth in Orissa emerge against the odds to serve the underserved and to tackle the proverbial “last mile” with a passion that many giants have struggled to emulate. Growing companies like Mela Artisans work to generate sustainable livelihoods for artisanal communities under a purposeful brand, while hundreds of for-profit health-tech innovators, like those found under the Baraka Impact umbrella, drive at top speed toward a world in which affordable access and health systems strengthening are a unifying mission. Companies such as Terra Cycle, Nothing New, Nike, and Interface are designing the future of circular economy modalities that leave behind zero waste—only “foods or nutrients” that create truer wealth through symbiotic economies of cycle while leveraging digital technologies that serve to dematerialize and decouple growth from harm. Likewise, revolutionary enterprises such as Solar Foods signal the potential of Schumpeter’s great “gale of creative destruction.” Their remarkable and, as yet, largely unknown, story of industry reinvention, has been sighted as one of the “biggest economic transformations of any kind” heralding the possibility of making food 20,000 times more land-efficient than it is today while propelling a future where everyone on earth can be handsomely fed, using only a tiny fraction of its surface (Monbiot 2020).

The biggest new management story of our time thus is not only about the individual business responses alone but about the rapid rise in collective impact. It’s about what scholars and leaders are calling business “megacommunities.” Consider the Global Investors for Sustainable Development. Taken together, they manage over $16 trillion in assets—and they are strategically prioritizing SDG investments across every sector and region of the world (GISD n.d.). Likewise, 2021 heralded the accelerated mobilization of over 200 companies such as Apple, Orsted, Woolworths South Africa, Salesforce, Patagonia, Tesla, Unilever, Schneider, Tata, Google, Levi Strauss, Microsoft, and Ikea, each one galvanizing their enterprises to be 100 percent renewable-energy leaders. In addition, this year also grew another worldwide partnership called Business Ambition 1.5°C, where hundreds more companies are rallying their 5.8 million employees, with headquarters in 36 countries, to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 via what’s called the “ambition loop” (United Nations Global Compact n.d.). In the last few months, we’ve seen the number of net-zero commitments rise to more than 1,500 corporations worldwide (Lubber 2021). And we all know that somewhere in the world, it’s already tomorrow. Microsoft, Interface, Unilever, and Natura—all and more are aiming higher, far beyond the sustainability agendas of “less bad.”

These are examples of trends and megatrends, almost overnight turning into transformative trajectories. Indeed, while researching this book, we were privileged to sit down with many of the vanguard CEOs leading the revolution. The 6,000 interviews now in the Fowler Center’s large and growing database involve not just the stuff of dreamers. They are the case studies of the bold, brave, and successful savvy of doers. Paul Polman, the former CEO of Unilever and chair of the International Chamber of Commerce, for example, spoke during a personal interview (Paul Polman and David Cooperrider, pers. comm., March 7, 2019) with penetrating purpose and urgent optimism, drawing on years of delivering industry-leading outperformance. He referred to the “shifting of the tectonic plates”—not a small step but a giant leap from our industrial age paradigm of business to its successor. He asserted:

What we are witnessing is a shift that is all-embracing, rapid, irreversible, extending to the far corners of the planet and involving practically every aspect of business life. What we are witnessing is a world increasingly divided by companies that are known as part of the problem and those that are leading the solution revolution in this, the era of massive mobilization. What we are witnessing is the birth of a comprehensive new enterprise logic, one that can not only create better value and truer wealth but can also be a platform for building the twenty-first-century company, the kind of enterprise that will be loved by its customers and stakeholder communities, emulated by its peers, and prized by all those who care about the next decisive decades of our planet.

The future, whether we are ready for it or not, is imminent. Some call what we are witnessing the worldwide solution revolution. Others call it the rise of a new mission economy. Whatever our age comes to be called, there will be winners and losers. Deep enterprise transformation will arrive, of course, in sputtering fits and starts. It will be sparked here and there by seemingly minor innovations. But then, as in every revolution, it will be set ablaze by adjacent embers, until the flames become something of a new Olympic standard, altering conceptions of business and society excellence forever.

We invite you into our journey, the call of our times, and the exciting, bold, and innovation-inspiring chapters written by the foremost thought leaders and successful CEOs in the field of management—and the business of betterment.

OUR JOURNEY

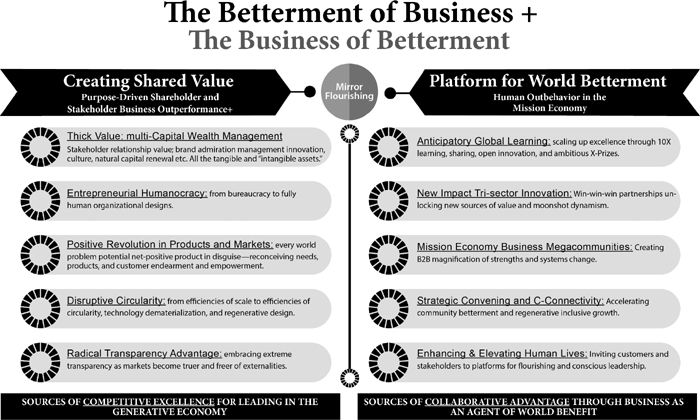

This book has been written to help leaders, entrepreneurs, change agents, executives, practical scholars, and young future managers join with and lead what Paul Polman referred to as the “solution revolution.” In this book, we serve as a guide to the emerging new enterprise logic—future-fit, future-ready, and future-forming—while helping to uncover the potentials for higher peaks of better prosperity, built on shared and regenerative value, with intergenerational concern and world-changing actualization. As we speak to each of the three parts of this volume and each chapter, we refer to figure 1.1 as the synthesis of our concept, as it relates to its meaning—and how—to elicit business outperformance together with business outbehavior.

Taken altogether, the chapters in this book form a natural union in their combined conviction that the fundamental purpose of business is building a better world and that there are multiplier opportunities before us—to outperform in competitive excellence terms and to outbehave the field in collaborative advantage terms. Moreover, the perspective offered here is new in its conception of how being a platform for world change “out there” is rapidly and paradoxically becoming one of the most inspiring and repeatable ways for bringing the “in here” of the enterprise powerfully alive.

As seen on the right side in figure 1.1, there is a largely underrecognized, underanalyzed, and underdeveloped new continent of leadership, a wide new axis of management potential, to be appreciated.

Of course, there are many facets to the framework. Each chapter will illuminate one or more of them in detail through major examples, data sets and trends, and the surfacing of deeper enterprise logics combined. In the spirit of foreshadowing the more precise threads woven through this book, there are three big lenses or ideas that make the positive loops between all the elements reverberate together even more powerfully. These cornerstones include: (1) the exciting new research on mission economy dynamism; (2) the idea of organizations as positive institutions or strengths-attracting platforms for “outbehavior”; and (3) the advanced leadership frontier of outside-of-the-building systems thinking that may be the most powerful way to bring “the inside of enterprise” to life. Let’s start with the idea of mission economics.

FIGURE 1.1 The mirror flourishing two-axis model of The Business of Building a Better World

1. Mission economics: Why so dynamic?

We know from economic history that epochal shifts in the logic of business have typically begun in response to underlying changes like what we call “the envelope of enterprise.” This includes tectonic shifts in society’s expectations, ecosystem and economic disruptions, and world system dynamics. The record of the last century shows that business organizations do not change easily from within, whereby changes outside the organization are most likely to be a trigger of fundamental transformations in the purpose, organizational designs, and leadership priorities of the firm (see Zuboff and Maxim 2004; Hamel and Breen 2007). We tend to think of these fundamental shifts in negative terms, for example, as devastating pandemics, world wars, and so on. These are of course powerful, often black swan events, and they are well-known change catalysts. But what’s also true and not as commonly appreciated is that fundamental shifts also come not only when society changes its mind but also when there is an enormous elevation of aspiration. This is where the research on mission economics becomes telling. Mission economies, just as negative macroevents often do, can propel mighty shifts.

Moreover, and according to the data of one of the economic theory’s rising stars (Mazzucato 2021; Mazzucato and Penna 2015), economic systems are most dynamically alive, technologically innovative, adaptive, prosperous, more fully human, and apt to propel betterment for all when they unleash an economy’s entrepreneurial spirit in a trisector way in the service of mission. How do we know? Mazzucato and her colleagues have studied over 100 examples across countries, cultures, and virtually every continent. The Kennedy-era moon-shot is a notable example in the work of Mazzucato (2020; 2021). We still thrill to John F. Kennedy’s mission economy when he said, “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone.” The word moonshot originally meant a “long shot” and is increasingly used to describe a monumental effort and lofty goal; in other words, “a giant leap” for humankind. What then, for example, have the studies of moonshot or mission economics discovered?

For one thing, missions create alignment of a society’s economic engine, entrepreneurial spirit, and symbiotic coalitions and partnerships, while becoming organizationally and technologically transformative. Landing a person on the moon propelled and produced unprecedented payoffs and large numbers of unpredictable spinoffs, creating entirely new markets and industries. It lifted a nation’s sense of hope and fueled inspiration, success, purpose, significance, and a desire to cooperate. And the record abounds of the economic productivity and vast benefits for all of humankind. In Apollo’s success, we experienced the birth and growth of the internet; small computers, nanotechnology; clean energy; X-rays; and the lists go on. Just the internet itself, as a public good and business catalyst, has enabled humanity to create thousands upon thousands of new businesses and millions of new jobs.

It is in this spirit that many of the chapters in this book see too, that to an extent unimaginable a decade ago, a macroworld project with a shared agenda calling upon all of humankind and unprecedented in scope and scale, is taking on form and substance. The original moonshot model offers insights and inspiration for pursuing global goals and “earthshots” today. To avoid some of the worst outcomes of climate change, the world must cut carbon emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and achieve net-zero by 2050. An achievement like that will, among other things, call upon investments and innovation in areas as different as building smart cities, transforming vast mobility industries, propelling the renewable energy economy, creating circular and regenerative approaches to manufacturing, turning waste into wealth, and building out regenerative agriculture and new food systems. That is the signature marker of what mission economies do.

Today’s earthshot, propose the authors, includes the example of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that is fast emerging and accelerating as the largest macroproject in recorded history. The scope and need dwarf the collaborations to heal the ozone layer or the global eradication of smallpox and the COVID-19 pandemic. It has dwarfed initiatives like the Marshall Plan, and it is ultimately even dwarfing humankind’s leap to the moon.

As one looks at figure 1.1, the idea of an emerging mission economy is both a megatrend and a valuable lens for making sense of advanced leadership (right axis) of the new theory of business, as well as a megatrend propelling and helping to explain the surge in the left “Creating Shared Value” side, depicting the rise in sustainable enterprise and regenerative business. Many things in this volume will make better sense as we appreciate mission economy dynamism.

2. Why is the Shared Value business paradigm—itself a relatively new enterprise logic—suddenly bursting out together with this largely undefined new emerging axis of management, where institutions show up as powerful platforms not just for outperformance, but for outbehavior?

For us, the concept of outbehavior is a good place to start and has several significant meanings. First, we draw attention to the work of Dov Seidman (2007) who wrote what he called a “how” book, not a “how-to” book recognizing that in our hyperconnected world of extreme transparency, there is no longer such a thing as private organizational behavior. In this internetworked economy, it is becoming increasingly difficult for organizations to succeed just based on what they make or do. It’s not long before someone else is making the product or service, better. It’s not long before others are doing it cheaper. People instantly compare price, features, and services effectively making the what into a commodity, where differentiation becomes blurred or blotted out, and distinctiveness itself is not long-lasting. How long is it before Costco has matched the price of a Walmart? Certainly not long.

Yet there is one area where tremendous variation exists, and it is not so much in outperformance as in outbehavior. In a world that’s yearning for trust and hope, it’s increasingly about the “how”—the outbehavior of bringing character strengths into the world, like honesty and integrity, hope and inspiration, or more humanity, fairness, courage, and wisdom into our communities. It doesn’t hurt that everything organizations do today can live online forever. Wherever organizations show up, their reputations arrive before they get there.

So while it’s true that the term outbehave is not to be found in dictionaries as are words like outperform, outfox, and outproduce, we posit that this kind of language truly matters. The idea that organizations can excel in the how of outbehavior needs such a word. Indeed, words make worlds. Seidman (2007, 17–18) is clear: “We know how to outspend and outsmart our rivals, but we know relatively little about how to outbehave them.… Show me a venture capitalist that asks entrepreneurs, ‘How do you plan to scale your values?’ and I’ll be interested in investing in their fund.” Could it be that in the twenty-first century, outbehavior is the strongest and higher-quality path to success and significance?

The second meaning of outbehavior is even more important. Harvard’s Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s newest leadership book Think Outside the Building: How Advanced Leaders Can Change the World One Smart Innovation at a Time (2020) indeed takes leadership to a new place. The days of viewing the corporation as a fortress or castle are gone, and what we are seeing emerge is “outside of the building thinking to improve the world.” For Kanter (who also has a chapter in this book) the next frontier for business leaders is to innovate outside of the building, at the interface of business and society, as an agent of world betterment. Still underanalyzed and underappreciated as a form of economic and human value, this kind of outbehavior is also a new kind of outperformance. For, according to Kanter, good companies can promote diversity in their ranks while making little difference in systemic racism outside of their walls.

The opportunity truly is to deploy a new leadership force for the world. The creativity of outside-the-building skills and sensibilities—activating allies; linking business communities; finding trisectoral assets in unexpected places; working to align complex and competing interests; opening minds; starting movements; harnessing tools for awakening enthusiasm for change; spanning professions of many disciplines; harnessing the renewable power of a positive purpose; creating big enough tents to unite and multiply siloed strengths—all of these are part of what Kanter calls “societal entrepreneurship” and what we refer to as the platform model of business as an agent of world benefit. Platforms are not programs for change; they are bigger than that.

Platform business models—for example Wikipedia, or Patagonia’s new activation platform that connects thousands of customers to one another and to hundreds of causes they can join—serve to harness and create large, scalable networks of users, human strength combinations, and resources that become ecosystems of cocreation. These produce scaled-up action and turn action into an effective antidote to despair while augmenting impact and driving human well-being. Platforms create communities and markets with network effects that allow users to interact, learn, enliven—and collaborate. Instead of being the means of production, platforms are the means to connection.

More academically, Cooperrider and Godwin (2011) in the Oxford University Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship talk about change making, with its usual focus on change management on the inside of the building, where the enterprise is the object of organization development and change. But then they pose a question, a thought experiment. What if we conceived of institutions not as the clients of change but as the change agents for attracting resources, partners, persons, communities, customers, coalitions, investors, and mission-aligned change makers of every kind? The larger concept involves the discovery and design of positive institutions:

Positive institutions are organizations and structured practices in culture or society that serve to elevate and develop our highest human strengths, combine and magnify those strengths, and refract our highest strengths outward in world-benefiting ways leading, ultimately, to a world of full-spectrum flourishing. (Cooperrider and Godwin 2011, 737)

The world is the ultimate context for the business of business is betterment. And because of this, every organization’s future will be of larger scope and greater purpose than it has been in the past. Every part of the field of management will indeed speak more fully to the destiny of humanity and nature.

So why—beyond being a force for good—will such platforms for world-changing as a new axis of advanced leadership matter in high-performance business terms? The answer, illustrated from the chapters and other recent research, revolves around what unites the right and left sides of figure 1.1. It’s called the “mirror flourishing” effect, and it proposes one radical message: building a better world is the most potent force on the planet—for generating on the inside of the firm the most engaged, empowered, and innovation-inspired enterprise every leader wants.

3. What if every business aspired to become a positive institution and platform for building a better world?

This is the question we want every reader to consider in the rich tapestry of chapters to follow. Could it be that as we as human beings doing good flourish and come more alive on the “in-here,” inside ourselves? Beyond the sustainability literature, there are now more than 500 scientific studies on this “doing good and doing well” dynamic. Steven Post and J. Neimark (2008) summarize many of them in a book titled Why Good Things Happen to Good People, whereupon they argue that this reverse flourishing, or mirror flourishing effect, is the most potent force on the planet. The possibilities are vast. For one thing, the reversal of so much of the active disengagement in the workplace, as well as the depression and heartsickness in our culture at large, might well be reversed and easier to accomplish than we think. There are more than 200 million businesses, literally countless numbers, operating across and around our blue planet. Imagine the positive mirror flourishing effect of millions of enterprise initiatives reverberating, scaling up, amplifying, and engaging—us.

OUR THREE-PART VOLUME

Our exploration begins in part 1, entitled “The Business of Business Is Betterment,” with a set of chapters that offer a new theoretical perspective for understanding how and why the business of building a better world is not only taking a quantum leap through the multistakeholder logic of “shared value creation” (see Porter and Kramer’s 2011 HBR classic and Kramer’s chapter in this book) but how this towering and expanding conceptual breakthrough of shared value is only the beginning.

Part 1 opens with a contribution by Marga Hoek in chapter 2, ranked by Thinkers50 as one of the top new management thinkers in the world. For Hoek, there is, as we previewed the concept, a powerful mission economy dynamic at work—a driving force and unstoppable force; “a new era in which there is every reason for businesses to want to save the world.”

Chapter 3, by Harvard’s courageous leadership theorist Rosabeth Moss Kanter, speaks to the new axis or next frontier of what she calls advanced leadership “outside of the building.” She writes: “It’s not enough to be good within their own operations and capabilities.” Advanced leadership changes the underlying institutions that shape systems. Moreover, “the gaps, the cracks between institutional walls, are the places that produce innovation opportunities.”

Mark R. Kramer follows, in chapter 4, with a short contemporary commentary on the classic article that he wrote with Michael Porter called “Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism—and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth” (2011). Kramer expands the idea that competitive advantage can be found in providing market-driven solutions to the world’s greatest social, ecological, and human challenges. The research, he concludes, is clear: “There is no reversing the fundamental recognition that managing business as a force for good is a winning strategy.”

In the next chapter (5) the originator of the concept of “triple bottom line” John Elkington and his colleagues Roberts and Kjellerup Roper write a fascinating contribution called “Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism.” The title tells it all. “A Green Swan,” the authors write, “delivers exponential progress in the form of economic, social, and environmental wealth creation.” If we are indeed entering the dynamism of perhaps the world’s most unprecedented mission economy—for which the authors provide evidence from all over the world—then we could be heading toward some sort of positive breakthrough future. Is it a certainty? Absolutely not. Is it a choice? Absolutely yes.

Finally, in the closing chapter (chapter 6) of part 1, CEO Naveen Jain, one of the world’s most imaginative entrepreneurs and exponential technology visionaries who helped found Singularity University and the X-Prize, articulates the power of the moonshot mindset with his coauthor John Schroeter. For them, the essence of moonshot thinking is thinking big. It’s what every business today needs to do. The authors share business examples, one after another, and conclude: “Now, in thinking big, what is the best way to create a $100 billion company? Answer: help a billion people live better lives.”

Part 2 of this book raises the stakes involved. It’s called “Net Positive = Innovation’s New Frontier,” and is composed of a set of chapters that together embrace the “best of the best,” vitally raising the bar with a great sense of urgency, impatience, and brutal honesty regarding the stakes involved. It begins with one of the world’s most respected CEOs, Paul Polman, former head of Unilever as well the International Chamber of Commerce, together with Andrew Winston, a strategic advisor to many leading companies including 3M, Marriott, DuPont, and others. The title of chapter 7 sets the stage: “Net-Positive Business and the Elephants in the Room.” The new horizon is a north star, not a short-term plan; there is no company today that can claim to be net positive. “Business has no choice but to play an active role,” say the authors and, “when we face the systemic hurdles head on, we can create net-positive businesses that serve the world.”

Next, in chapter 8, Bart Houlahan and Andrew Kassoy, cofounders of the B-Corporation movement, trace the historic shift happening in business toward true markets, extreme transparency, real accountability, and the toppling of the statue of Milton Friedman; that is, the view that the only business is business. By the start of 2021, there were 3,800+ certified B Corporations in more than 70 countries.

Raj Sisodia, the cofounder of the conscious capitalism movement, follows next in chapter 9 and speaks to the kind of mirror flourishing that can happen when we achieve a Copernican revolution, where the business of betterment is at the center of the business universe: “We need to put the life-affirming essentials—human and planetary flourishing—at the center. Everything else, including profits, must revolve around and serve those transcendent goals.”

Chapter 10 by R. Edward Freeman, often called the academic father of the stakeholder theory of the firm, along with coauthors Joey Burton and Ben Freeman, presents the data sets and the proposal that stakeholder capitalism is here to stay, and that we are on the cusp of the new story of business. And unlike others that say it’s purely being driven by the younger generations (which is true), the larger reality is that what we are witnessing is “three generations, one voice.” Thus: “We must be the generations that create a better world for those to follow us.”

In chapter 11, Gillian M. Marcelle and Jed Emerson—two of the great thinkers in the arena of blended capital and multidimensional capital—ask us to be inspired by and to “incorporate the alternative understandings of value and stewardship” that emanate from ancient African, Asian, indigenous, and feminine traditions. One aspect is a return to the reality and quality of relational being, where we see and acknowledge the deepest qualities that make us human.

Finally in chapter 12, Roger Martin, a prolific researcher and business school dean, provides a remarkable history lesson—the story of how business models stripped humanity out of management theory. He argues that any business guided by these models “will be doomed to failure” as the humans involved will come to understand the missing humanity and feel its counterproductive impacts. They will fail “because humanity will eventually undermine systems devoid of humanity.” High on the agenda of the business of building a better world is a fully human design, not as an afterthought but a centrally embedded reality.

In part 3 (called “The Ultimate Advantage: A Leadership Revolution That Is Changing Everything”), the authors agree that the human dimension and shift from sustainability-as-less-harm to the quest for full-spectrum flourishing is a drivingforce for all the hope and promise of this moment of leadership reset. In management, Peter Drucker spoke to us (David Cooperrider and Peter Drucker, pers. comm., 2003) in common sense terms when he said: “Just as a vital organ such as one’s heart cannot thrive in a body overcome by cancer, a business resides in, our societies, the biosphere, and the earth.” Indeed, worldviews of bifurcation or separation no longer serve us. There is no long-term business case at all for destroying the envelope of enterprise. Can we acknowledge the interdependence of business and society, that one cannot flourish without the other, the concomitant systems logic of mirror flourishing?

To do this, argue the authors, we must essentially elevate our view of what it means to be human. They turn to the crossroads of state-of-the-art human science, the biology of enlivenment, and the field of neuroscience (some of it made possible by technology advances like MRI) that all show that altruism is real and that impulses to goodness and caring (for newborns, for example) reside in our genes. We see increasing validation of the fact that emotions of love and kindness are precious and vital to every one of us in life; that rich meaning and activation of moral purpose raises our happiness and our immune systems; that extreme isolation and loneliness kills; that when a friend living less than a mile away becomes happy, it will increase the probability that you are happy by 25 percent (Fowler and Christakis 2008), whereby our states of well-being, even dimensions of our physical health flow through networks, and more.

In chapter 13, Kim Cameron, one of the founders of the field of positive organizational scholarship (POS), shares his insights on the back of the study of hundreds of organizations that have faced major crises. In an overwhelming number of these, unprecedented levels of crisis were followed by deteriorations in productivity, quality, trust and ethics, and customer and stakeholder loyalty. Yet a select few organizations flourished and bounced back higher. What was the difference that made all the difference? In every exceptional case, it had to do with outbehavior where leaders were described in virtuous terms or descriptors: compassion, dignity, forgiveness, kindness, trustworthiness, and higher sense of purpose in their cultures. Cameron concludes: “In considering how business can be a better contributor to world benefit, prioritizing virtuousness, may be among the very best strategies to pursue.”

If that sounds radical, then chapter 14 by Michele Hunt, former EVP of Herman Miller and now researcher and writer, may push the envelope. Can a company be powered by love? How can a great leader not be in love with their bold dreams, with authentic and mighty purpose, with unleashing the human excellence that people are endowed with, and indeed with serving? She argues that love is the most powerful, transcendent, and energetic force in the lives of real leaders. Under Hunt’s leadership at Herman Miller, the company became Fortune’s “Most Admired Company,” the best company for women and working mothers, the most environmentally responsible in the United States, and named the “Best Managed Company in the World.” This was love in action.

In chapter 15 Chris Laszlo (lead author of an emerging Stanford University business classic, Flourishing Enterprise: The New Spirit of Business) and Ignacio Pavez from Chile share that we are in the midst of a consciousness revolution and one that’s changing everything. Based on their studies of “positive-impact corporations” committed to going beyond the Hippocratic oath, where doing less harm is no longer an industry-leading leadership ideal, they define success by positive impact value. Their aim is “to increase economic prosperity, contribute to a regenerative natural environment, and improve human well-being.” This chapter brought us to reflect on many wisdom traditions and great adages, for example, the words of Thomas Aquinas when he said: “To live well is to work well”—where good living and good working are inseparable.

Chapter 16, by Udayan Dhar and Ronald Fry, is based on a grounded theory study drawn from perhaps the largest innovation bank in the world on the topic of the business of world betterment. Housed at the Fowler Center for Business as an agent of world benefit at Case Western Reserve University, the AIM2Flourish database holds more than 3,000 interviews with businesses from over 130 countries whose mission is to advance both the UN SDGs and create economic value for investors. Dhar and Fry rigorously draw a randomized subset of 36 business and society innovations from this dataset and uncover a series of clear success factors of nearly every element of our dual-axis model. Their analysis uncovers “recognizing the enterprise [itself] as a change agent,” the platform model of positive institutions, as well as the success factors of social and ecological embeddedness; long-term orientations to value creation; incorporation of circular value chains; and the convening power of collaborative boundary spanning.

The final chapter in this volume is about the thrill of putting all of this—notably the elements from figure 1.1—together and in practice. Chapter 17 is written by Nadya Zhexembayeva, known for creating a new discipline beyond change management called reinvention, and David Cooperrider, thought leader and originator of the theory of appreciative inquiry. Together they share the skills and sensibilities of the reinvention mindset and how it counters the Titanic syndrome, where patchwork never succeeds. They distill key lessons with their own experiences of reinvention, through helping companies bring hundreds and sometimes thousands of internal and external stakeholders “into the room” as collaborating partners. Nadya, David, and their colleagues have helped lead Appreciative Inquiry Reinvention summits with companies such as Apple, Interface, Clarke Industries, Walmart, Whole Foods, and with business megacommunities such as the UN Global Compact, which now involves some 10,000 corporations and regional networks of companies in every region of the world.

Their number-one conclusion after years of reinvention design on a vast array of management topics? The business of betterment is the most potent force on the planet for generating—both on the inside and outside of the firm—the most engaged, empowered, and innovation-inspired enterprise every leader wants. And what the world needs.

REFERENCES

Cooperrider, David L., and Lindsey Godwin. 2011. “Positive Organization Development: Innovation-Inspired Change in an Economy and Ecology of Strengths.” In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, edited by Gretchen M. Spreitzer and Kim S. Cameron, 737–50. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fink, Larry. 2021. “Larry Fink CEO Letter.” BlackRock. https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter.

Fowler, James H., and Nicholas A. Christakis. 2008. “Dynamic Spread of Happiness in a Large Social Network: Longitudinal Analysis over 20 Years in the Framingham Heart Study.” BMJ 337, a2338. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2338.

Freedman, Andrew. 2019. “More Than 11,000 Scientists from around the World Declare a ‘Climate Emergency.’” Washington Post, November 5. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2019/11/05/more-than-scientists-around-world-declare-climate-emergency/.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2002. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Back Bay Books.

Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance (GISD). N.d. “The GISDAlliance.” Accessed May 12, 2021. https://www.gisdalliance.org/.

Hamel, Gary, and Bill Breen. 2007. The Future of Management. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kanter, Rosabeth M. 2020. Think Outside the Building: How Advanced Leaders Can Change the World One Smart Innovation at a Time. New York: PublicAffairs.

Lang, Kristen. 2020. “Building a More Equitable, Just and Sustainable Economy Is No Longer an Ideal. It’s Imperative.” Reuters Events—Sustainable Business, October 8. https://www.reutersevents.com/sustainability/building-more-equitable-just-and-sustainable-economy-no-longer-ideal-its-imperative.

Lubber, Mindy. 2021. “Net Zero Gaining Momentum like Never before among Investor and Business Community.” Forbes, January 6. https://www.forbes.com/sites/mindylubber/2021/01/05/net-zero-gaining-momentum-like-never-before-among-investor-and-business-community/?sh=3b9186af8bf0.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2020. The Value of Everything. New York: Public Affairs.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2021. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. New York: Harper Business Books.

Mazzucato, Mariana, and Caetano C. Penna, eds. 2015. Mission-Oriented Finance for Innovation: New Ideas for Investment-Led Growth. London: Pickering & Chatto.

Monbiot, George. 2020. “Lab-Grown Food Will Soon Destroy Farming—and Save the Planet.” Guardian, January 8. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/08/lab-grown-food-destroy-farming-save-planet.

Porter, Michael E., and Michael R. Kramer. 2011. “Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism—and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth.” Harvard Business Review, January. https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value.

Post, Steven, and Jill Neimark. 2008. Why Good Things Happen to Good People: How to Live a Longer, Healthier, Happier Life by the Simple Act of Giving. New York: Broadway Books.

Ripple, William J., Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R Moomaw. 2020. “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency.” BioScience 70, no. 1: 8–12.

Seidman, D. 2007. How: Why How We Do Anything Means Everything … in Business (and in Life). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

United Nations Global Compact. N.d. “Business Ambition for 1.5°C.” Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/take-action/events/climate-action-summit-2019/business-ambition.

Zuboff, S., and J. Maxim. 2004. The Support Economy: Why Corporations Are Failing. New York: Penguin Books.