CHAPTER 1

CREATE LIKE YOUR LIFE DEPENDS ON IT

WHY CREATIVITY MATTERS

I’ve been collecting signals on the landscape, indicators that we are increasingly valuing our uniquely human ways of thinking and creating in our business life. One signal comes from the management consultancy Capgemini. In 2015, Capgemini published a report titled “When Digital Disruption Strikes: How Can Incumbents Respond?” It begins with this striking sentence: “Since 2000, 52% of companies in the Fortune 500 have either gone bankrupt, been acquired, or ceased to exist.”1

The core reason for this failure has been chalked up to an inability to adapt. But let’s dig deeper as to why it’s hard to adapt. Part of it involves the “too big to fail” assumption and superiority complex that emerge when organizations find themselves at the head of the pack. But where does that mindset come from? It is not enough to say that these firms don’t innovate quickly enough. They get complacent and stuck. Michael Forman, chairman and CEO at FS Investments, told me that as organizations get larger and more focused on risk management, they easily fall into what he calls “the tyranny of no.” “They solve for ‘no’ instead of for ‘yes.’ Solving for ‘yes’ is the fulcrum of creativity.” He observed that the larger reason for why successful companies fail is that they do not cultivate their capacity for human creativity.

A second signal showing up in an unexpected place comes from the World Economic Forum (WEF). In 2016, the WEF predicted that by 2020, creativity would rank as the number 3 job skill. Consider that the WEF had ranked creativity as the number 10 job skill in 2015. What is interesting is that they predicted critical thinking and complex problem-solving would rank first and second by 2020. But guess what? Creativity requires critical thinking and complex problem-solving—so we essentially have creativity leading the pack in important job skills for the future of work (see Figure 2).

Yet another sign I’ve witnessed was in the Showtime hit series Billions. Character Wendy Rhoades is among the C-suite of executives at Axe Capital. She counsels the group of intense, testosterone-driven venture capitalists to tune in to their inner voice, learn to meditate, and visualize success. I am increasingly seeing the value of people with backgrounds in the humanities, psychology, and cognitive science in unusual spaces.

Perhaps the biggest signal of all occurred in the summer of 2019. Business Insider announced that a convening of leaders of Fortune 100 firms had culminated in an acknowledgment that stakeholder value was as important as shareholder value.2 While many have a wait-and-see attitude about how these companies will demonstrate through their actions that people (and the planet) matter just as much as profit, it is significant that these leaders spoke this value out loud.

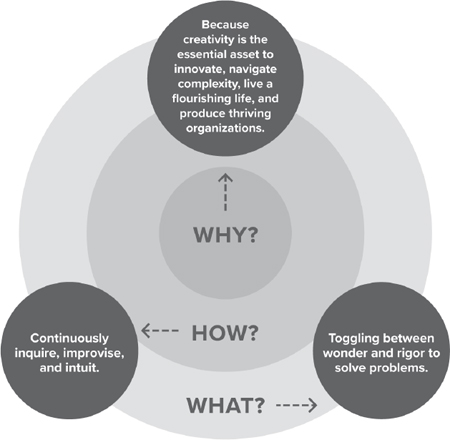

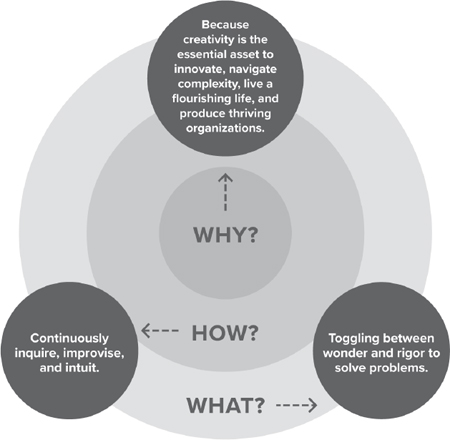

Figure 2. What is creativity?

WHY DO WE DISMISS CREATIVITY?

Research from Steelcase, a furniture design company, presents interesting insights about collaboration at work and creativity.3 They surveyed 4,500 people in Germany, France, England, Spain, the United States, and Japan. The following were some of the more relevant points regarding creativity:

14 percent were not given a chance to express their creativity.

55 percent wanted to be more creative in their role.

Generation Y and Generation Z showed more creative ambition than older workers (60 percent versus 50 percent).

-

Creative blocks included these:

Uninspiring space (20 percent)

Existing workload (36 percent)

A lack of guidance or permission to be creative (19 percent)

Outdated technology (20 percent)

In spite of all these signals on the landscape, I’m convinced that we don’t hear creativity emphasized more in the boardroom because we don’t actually understand creativity. I define creativity as our ability to toggle between wonder and rigor to solve problems and produce novel value. While many companies are trying to figure out innovation, most corporate cultures rarely utter the word creativity, and there is not a carved-out space in the boardroom for creativity. This goes back to the ways that we have partitioned it off as being only in the domain of the arts, making creativity appear inaccessible and in the realm of the few, not the many. In his 2007 TED Talk, Sir Ken Robinson, well-known adviser on education in the arts, spoke about the decline in creative confidence. He shared how when kindergarten students are asked, “Who wants to be an artist?” the majority of hands fly up. By high school, that cheerful endorsement of the arts as a career path dwindles down to less than a quarter of the students.

Perhaps creativity feels so inaccessible because it can be such an ambiguous process. It is not formulaic. It is complex. That lack of a rote, step-by-step approach can make it really uncomfortable. The arts have become the default space where we identify creativity because artists are required to sit with the ambiguity of not knowing where their creative process will lead them. They commit themselves to wrestling with the discomfort of it all.

LinkedIn produces a podcast about work called Hello Monday. In one episode, the actor Laura Linney was interviewed by Jessi Hempel about what makes for good criticism.4 In it she discussed the value of “sitting with discomfort.” As an artist, she has grown to expect this as part of her work in creating a character and collaborating with other actors. I was struck by how much she accepted that discomfort and the ambiguity of it all.

A creativity leap entails our seeing and listening with wonder and rigor in order to sort through the ambiguity and uncertainty of a work process. The awareness that Linney described points to the amount of astute seeing and listening we must do in order to create. It is only through that deep listening and observation that we uncover the finer points that need tuning and realignment.

Fundamentally, the arts teach us how to see things from different perspectives. For example, when you learn how to draw a vase, you must observe not only the solid matter in front of you but all of the context around the vase. An early exercise may be to start with a contour line drawing, only drawing the outline of the object in front of you. By default, you wind up drawing the “negative space.” Negative space refers to the in-between bits of color, light, and shadow that begin to take shape in the space outside of the boundary lines of the object. Think of the Rubin’s vase optical illusion, also referred to as the figure-ground vase. In this puzzle drawing, you might alternate between seeing either a woman’s profile or a vase. It is a classic way of demonstrating that what we see can be amplified, diminished, or crystallized if we not only look at what is obviously in front of us but also shift our focus a bit to what is on the periphery or just beyond. It helps us to question our assumptions about what is, and to see things from varied perspectives.

Julian Harzheim and I met in Shenzhen, China, in 2018, at the European Innovation Academy (EIA), a business accelerator program. It wasn’t enough that he was a German studying at Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal, and showing up in Shenzhen with social impact desires. What dazzled me further was the story he shared over a coffee about starting Creative Hub at Nova.

During the first week of business school in Lisbon, one of Julian’s professors asked the class, “How many of you believe that creativity will be one of the most important skills in the future?” All hands shot up. When the professor asked this follow-up question, “How many of you believe you are creative?” the majority of students’ hands went down. Julian saw a problem—and an opportunity. And so he started Creative Hub with a handful of other MBA students as an experiment, as a platform to bring forward new ideas. One workshop focused on storytelling and was run by graffiti artists. Another event, called the Lemonade Challenge, gave students 20 Euros to come up with better ways to market lemonade.

Julian started Creative Hub with a bit of wonder and dug in with rigor to bring it to fruition. Applying our human capacity for creativity and inventiveness to problem-solving was a game changer for him. It has made a huge impact on his life: “It gave me the confidence to believe in my ideas. It was also a pilot test phase for me to see how I could build a team with only a vision. And nothing else.” Today Julian has graduated and works with a start-up in Lisbon whose mission is to end wildfires in Portugal.

These are the benefits of sitting with the discomfort and ambiguity that arise during the creative process. In Julian’s case, this push outside of his comfort zone helped him build the muscle of believing in his own ideas. Instead of avoiding the discomfort of uncertainty, he grappled with it. Winston Churchill said, “When you’re going through hell, keep going.” There is no other, romanticized way around it. This is the rigor of the creative process.

MAKING CREATIVITY ACCESSIBLE

Does your organization have a department of innovation, an innovation lab, or an innovation studio? If it does, that is great, because it indicates a desire to not continue doing things in the ways they have always been done. But going from having an innovation center to having a culture of innovation demands a creativity leap. It requires intentionality and the integration of a new mind-set at all levels of the organization. Otherwise, you have created just one more silo in your company.

People throw around the word innovation all the time; sometimes we end up talking around each other without getting to the real definition. What do we mean by innovation? Innovation is invention converted into financial, social, and cultural value. Furthermore, the engine for innovation is creativity. That means that if we truly want to innovate, then we must design systems, processes, and experiences in our work environments that allow us to be creative and catalyze invention.

If all we are doing is setting aside new departments or spaces that we designate as the space in which to innovate, then it is as if we are saying there is a separate time and space to be creative and to be productive. And that just is not so. Creativity is a productivity play. That is why it is essential for business, not just some frilly, extraneous add-on. Taking the leap to build an organization-wide creative capacity is the single best way to continually innovate.

The first step is making creativity a resource that is accessible to all the people in your organization. Defining creativity as a competency consisting of wonder and rigor, and exercised through inquiry, improvisation, and intuition, is one way to democratize it. Viewed from this lens, creativity becomes available to all of us.

Inquiry, or curiosity, is the foundation, because without the ability to ask questions, you cannot be self-reflective; you are stuck. One of the major takeaways I have gotten from Warren Berger’s book A More Beautiful Question is that asking questions is really a way of thinking.5

Improvisation is your ability to be present in the now and to be responsive with those around you. There are rules to improvisation; it is not doing whatever you feel like doing. The beauty and fun of improvising is that you get to stretch and rebound off of minimal structures in order to create something entirely new. Improvisation is all about the remix.

Intuition is that connection between the heart and mind, grounded in your gut. It is unconscious pattern recognition. It is often what fuels us to finally make that creativity leap.

Inquiry, improvisation, and intuition don’t need to be followed in any particular formulaic order. Their use is situational, and there is an ebb and flow between them resulting in insights. This is what makes creativity the engine for innovation.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defined flow as the state during which you are so immersed in an activity that nothing else matters. You are neither aware of the time nor self-conscious. Csikszentmihalyi considers flow as the means to creativity and the secret to happiness. He writes about creativity as moments that make life worth living when there is total flow.

That flow can happen on both the individual and organizational levels, but not until we stop ghettoizing creativity and relegating it to the domain of artists. The false dichotomy of creatives versus noncreatives puts the onus of creativity solely on artists. This isn’t fair. To expect that all creative outcomes must stem from artists is a lot to ask—especially given the fact that in the United States we don’t set up artists to succeed in terms of funding or real acknowledgment of their contributions to our economy. Instead, we should all share the responsibility of being catalysts for creativity because creativity resides in all of us.

When I began my interview with Jeff Benjamin, the COO at Fitler Club, a full-service urban social club for professionals, he initially said, “I don’t view myself as a creative.” There goes that qualifier again: “a creative.” Let’s remove the “a” and just sit with “creative” for a moment. By the middle of our conversation, Jeff made an enlightened remark: “Creativity is as individual as a snowflake. My restaurant managers are my customers. They’re my table. I’m waiting on them.” And that is where he sees his creative energy surging.

As Jeff came to realize, to be dynamic at anything—as EVP of operations, an attorney, a scientist, an entrepreneur, or a plumber—you must be consistently creative, drawing on your capacity for asking audacious questions, working off script, and following your gut instincts.

CREATIVITY IS HOW WE LEAP FORWARD

Humans are creatures of habit and tend to crave certainty. And when you need to stay in your lane, it may be safe to establish benchmarks that are local and accessible and germane to your industry. But benchmarks are relative boundaries. The broader you need your thinking to be, the broader should be your benchmark.

When I was a professor and developed a strategic design MBA program, I fell in love with the design thinking process. I appreciate it as a problem-solving tool that organizations can apply to produce more customer-centered products and services. In addition to empathy, prototyping, and visualizing data, one of its important hallmarks is lateral thinking. Lateral thinking is the ability to learn from sectors and practices both adjacent to you and far away from the way you typically do business. For example, if you are a tech firm, you might explore theatrical production to learn about project management, or you might intentionally align with an instigator such as BCG Digital Ventures. Lateral thinking opens you up to the opportunity of choosing new benchmarks so that you can make creativity leaps. I realize now that this is what allowed the manufacturing teams I once worked with to innovate old designs and create freshly styled brassieres.

Years ago, I lived in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and then Porto, Portugal, making bras and panties for the Victoria’s Secret brand. During this short stint in my career working in apparel fashion sourcing, I learned the logistics and manufacturing side of the fashion business. Working directly on the ground with fabric mills and cut-and-sew factories was an amazing education about production and quality control. A brassiere is a relatively complex object. It consists of more than 30 components, and the ability to deliver consistency in fit and color over multiple sourcing locations is no small feat.

Often, the factories would establish benchmarks, or standards, by gauging what competitors in the same category were doing. Standards were established by looking internally, within the same sector. But consistently, the biggest breakthroughs in design direction came not only from using other apparel or fabric companies as reference points but also from implementing engineering workarounds and ingenious materials selection.

It was when we broke out of our norms and looked laterally to adjacent areas or to totally new realms that inspiration materialized. For example, at the time, laser cutting and 3-D digital printing were relatively new technologies, just being introduced into apparel production. It was remarkable to see the engineers and fashion designers troubleshoot new and interesting ways to develop edging and cutouts from fabric where shrinkage and the fibers’ melting points had to be considered.

New benchmarks have been Kevin Bethune’s raison d’être as a leader in strategic design. Kevin is the founder and chief creative officer at dreams • design + life, a self-described “think tank that delivers design and innovation services using a human-centered approach.” He told me his story of working at Nike after earning his MBA and gradually inching his way into working with the design teams. One of the ways he did this was by regularly contributing to their brainstorm wall and posting exemplars that came from new and different areas. He would ask, “Have we looked outside of the Nike walls? What other trends are shaping this space?” At the time, he was not formally trained as a designer. His first degree was in engineering. So his nonexpert perspective added fresh-eyes value to identifying new benchmarks.

Kevin describes creativity as “the opportunity to combine, recombine, disrupt, or creatively destroy existing things and known elements into new and interesting combinations.” He certainly had to do this later in his career as cofounder of BCG Digital Ventures, a corporate investment and incubation firm. Kevin and his team convinced start-ups to remove themselves from the safety of their own environment to reorient themselves and learn how to research and collect new insights. Space matters in establishing new benchmarks and navigating complexity. In fact, BCG Digital Ventures experimented with space to the extent that some rooms were in the shape of a hexagon to help people work more fluidly and in truly multidisciplinary ways.

When you are trying to leap into new frontiers as a business, you must identify new landmarks and new benchmarks, and get into a new space to work. When you are trying to break out of the mold, you must be audacious to make that creativity leap into new territory.

CREATIVITY LEAP EXERCISE

CREATIVITY LEAP EXERCISE

FOR YOU

Become a clumsy student of something. Cultivate a new hobby. Marvel at how good you become at asking questions, improvising, building on mistakes, and intuiting.

Become a clumsy student of something. Cultivate a new hobby. Marvel at how good you become at asking questions, improvising, building on mistakes, and intuiting.

FOR YOUR ORGANIZATION

Build on Kevin Bethune’s model: What are the trends and the exemplars outside of your industry that your company should be paying attention to?

Build on Kevin Bethune’s model: What are the trends and the exemplars outside of your industry that your company should be paying attention to?

CREATIVITY LEAP EXERCISE

CREATIVITY LEAP EXERCISE Become a clumsy student of something. Cultivate a new hobby. Marvel at how good you become at asking questions, improvising, building on mistakes, and intuiting.

Become a clumsy student of something. Cultivate a new hobby. Marvel at how good you become at asking questions, improvising, building on mistakes, and intuiting.