Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Culture Puzzle

Find the Solution, Energize Your Organization

Mario Moussa (Author) | Derek Newberry (Author) | Greg Urban (Author) | Brian Nishii (Narrated by)

Publication date: 06/22/2021

In a world that changes at a dizzying pace, what can leaders do to build flexible and adaptive workplaces that inspire people to achieve extraordinary results? According to the authors, the answer lies in recognizing and aligning the elusive forces—or the “puzzling” pieces—that shape an organization's culture.

With a combined seventy-five years' worth of research, teaching, and consulting experience, Mario Moussa, Derek Newberry, and Greg Urban bring a wealth of knowledge to creating nimble organizations. Globally recognized business anthropologists and management experts, they explain how to access the full power of your culture by harnessing the Four Forces that drive it:

Vision: Embrace a common purpose that illuminates shared aspirations and plans.

Interest: Foster a deep commitment to authentic relationships and your organization's future.

Habit: Establish routines and rituals that reinforce “the way we do things around here.”

Innovation: Promote the constant tinkering that produces surprising new solutions to old problems.

Filled with case studies, personal anecdotes, and solid, practical advice, this book includes a four-part Evaluator to help you build resilient organizations and teams. The Culture Puzzle offers the definitive playbook for thriving amid constant transformation.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

In a world that changes at a dizzying pace, what can leaders do to build flexible and adaptive workplaces that inspire people to achieve extraordinary results? According to the authors, the answer lies in recognizing and aligning the elusive forces—or the “puzzling” pieces—that shape an organization's culture.

With a combined seventy-five years' worth of research, teaching, and consulting experience, Mario Moussa, Derek Newberry, and Greg Urban bring a wealth of knowledge to creating nimble organizations. Globally recognized business anthropologists and management experts, they explain how to access the full power of your culture by harnessing the Four Forces that drive it:

Vision: Embrace a common purpose that illuminates shared aspirations and plans.

Interest: Foster a deep commitment to authentic relationships and your organization's future.

Habit: Establish routines and rituals that reinforce “the way we do things around here.”

Innovation: Promote the constant tinkering that produces surprising new solutions to old problems.

Filled with case studies, personal anecdotes, and solid, practical advice, this book includes a four-part Evaluator to help you build resilient organizations and teams. The Culture Puzzle offers the definitive playbook for thriving amid constant transformation.

CHAPTER 1

The Pharaoh and the CEO

Seeing What’s Right in Front of Your Nose

He rode with his head held high into the vast luminous valley, gazing from a white-gold chariot at the surrounding cliffs. To his regal eyes, they formed a shape reminiscent of the symbol for “horizon.” Instantly, he knew. In a flash of divine inspiration, he decided to build a great city on that barren spot. He would call it “The Place Where God Appears.” Then and there, he celebrated the momentous occasion, kneeling before a makeshift altar with an offering of bread, beer, plants, fruit, and incense. As he rose to his feet, he ordered that stone slabs mark the boundaries of the metropolis from where he would rule the world.

His name was Pharaoh Akhenaten, and he governed Egypt in the fourteenth century B.C. During his reign, he introduced a dizzying array of cultural innovations, ranging from novel artistic and architectural styles, newly coined words and phrases that expressed his self-aggrandizing ideology, and a thorough overhaul of administrative structures. Most remarkable of all, he created a radically unorthodox set of religious beliefs that installed him at the center of the universe as the Sun God. Before Akhenaten, pharaohs acted as intermediaries between the people and hundreds of gods. But now the pharaoh was himself a god.

Had you lived under Akhenaten’s rule, would you have appreciated him as an innovative visionary, or would you have dismissed him as a megalomaniacal madman? Scholars have vigorously debated this question for nearly a century. Many have pointed out that his subjects must have admired his cultural innovations in art, politics, and philosophy, while others have insisted that few would have easily abandoned deeply ingrained religious beliefs.

Most of the pharaoh’s subjects, it turns out, did not embrace the big change. Widespread unrest, a collapsing economy, and Akhenaten’s death, a mere 17 years into his reign, ended the cult of the Sun God. Akhenaten’s successor, Tutankhamen, honoring the wishes of the people, reintroduced the cherished gods and restored their temples.

This tale of a prideful pharaoh who fails to change long-standing cultural beliefs remains keenly relevant today. Even if you occupy a position of supreme power—as a supervisor, a project manager, or a global CEO—you need to understand your organization’s culture. In an era of unprecedented change, thriving in the “next normal” will take humility and hard work. If you attempt to exert godlike control, you will end up watching your plans for a prosperous future join Akhenaten’s vision in the graveyard of failed projects.

Beginning to Assemble the Culture Puzzle

The history of events in Egypt some 4,000 years ago repeats itself every day in the world of sprawling corporate campuses when modern managers choose the path of Akhenaten. Obsessed with building their “shining city,” they mandate massive cultural changes, hoping an entirely new way of doing things will propel their organizations to global domination.

“We’re going to cut out the expensive, boring stuff and just build the top.”

Picture “Sphynx, Inc.,” an underperforming multi-billion-dollar company whose CEO Lyle King experiences a flash of inspiration, a vision of a whole new set of beliefs and behaviors that will motivate the Sphynx employees to achieve greatness. “Forget the stodgy old way we’ve done business in the past,” King declares. “The brand-new Sphynx will make Apple look like a lemonade stand.”

CEO King dictates the desired changes and sits back to watch the magical transformation. Do people eagerly embrace the new way of conducting business? Maybe. Maybe not. They might pay lip service to the new values, while in their hearts they harbor a tight ball of resentment and resistance. If so, in subtle yet powerful ways, they will sabotage the culture change, and 12 months later, with Sphynx’s balance sheet bleeding red ink, the board will have to show the once godlike CEO the door.

In 2013, Harrison Weber, the editorial director for WeWork, a company that designs flexible workspaces for organizations and freelancers, listened to a stunning vision every bit as grand as Lyle King’s and Akhenaten’s. Late at night, not altogether sober, he was standing on the ledge at the top of the 57-story Woolworth Building in Manhattan. Next to him swayed two tipsy coworkers and a fellow named Adam Neumann, the six-foot-five charismatic founder of WeWork, who was sketching his grand vision of a brave new world where people worked in amazing new environments that would inspire them to achieve unparalleled results.

Weber vividly recalled the moment. “I was up there with him on the top of the world, and he said, ‘Everything is going to be amazing.’” Neumann’s idea for what he called a “physical social network” would, he proclaimed, transform any business into a sleek new world-beater. As the New York Times reporter Amy Chozick described it, WeWork would create a space where “work and play bled into one” and would “elevate the world’s consciousness.” Weber put it more simply: “It was like, wait, you mean life. What you’re talking about is just regular life.” Maybe so, yet there was nothing “regular” about the way investors responded to Neumann’s WeWork vision. The company quickly attained a $47 billion valuation. But then a series of failed projects rapidly eroded that sky-high number. By 2020, just seven years after that evening when Neumann and his three employees had gazed like kings down on the Manhattan cityscape, the company’s value had plummeted to roughly $9 billion. A failed IPO in late 2019 exposed Neumann’s vision as little more than cult-like hype. Masayoshi Son, head of the Japanese investment company Soft-Bank, bet a staggering $4.4 billion on WeWork. Asked to explain the regrettable decision, Son replied in his tentative English: “Well, he had no business plan. But his eyes were very strong. Strong eyes, strong, shining eyes. I could tell.”

Any powerful leader can command sweeping change. But commands alone do not get the job done. If you merely proselytize from a perch, as Neumann and Akhenaten did, bulldozing ahead with wildly ambitious initiatives, you will find yourself mired in a minefield of resistance and even sabotage. You must solve what we call the culture puzzle.

No other animal species rivals human beings in their ability to learn, adapt, and cooperate in the pursuit of basic needs and lofty aspirations. You can scarcely imagine the smartest gorillas, whales, or dolphins founding a religion or incorporating a global conglomerate. The ability of human beings to form a culture, adapting the way we think and act to cope with ever- changing conditions, has enabled us to accomplish astonishing feats. We have built cities and left footprints on the moon. And yet: toxic cultures have demolished an endless parade of organizations and societies. Just take a look at Akhenaten, Neumann, and thousands of other grand visionaries who have done more harm than good with their ambitious but arrogant plans for success.

What knowledge and skills do you need in order to build a strong, vibrant, agile, and adaptive culture, where people eagerly engage in the meaningful work that will achieve extraordinary results for the organization? We have written this book to answer that question. We bring a lot of experience to the undertaking. During a combined 75 years’ worth of research, teaching, consulting, and training, we have learned a few fundamental lessons about what makes a culture healthy and how you can make it grow to meet your goals.

Lesson #1: Success begins and ends with culture. Most culture- building mistakes occur when a leader views culture as an add-on component, a mere sideshow to the main concerns of running a successful enterprise. Too often, strategy, finance, and operational issues occupy the front seats of the bus, with culture riding along in the back. In our view, culture should take the wheel. Strategy, finance, operations, and their cousins do not fulfill basic human needs. Culture does. It fulfills the needs that have been hardwired into our basic biological makeup, needs as essential to our daily lives and well-being as food, air, and water. It’s no exaggeration to say that culture makes us human.

Which leads to Lesson #2: Culture satisfies some of our most important needs. We all require deep and rewarding relationships, we all love to solve problems that reap rewards for our group, and we all yearn for dignity and respect as we get ahead in life. The many different strategies people employ in the service of those motivations defines their culture. You never do it alone. In anthropological terms, it takes a tribe. Its members undergo the most profound education, learning, in the end, how to live in the tribe and contribute to its success. (Chapter Two examines how tribes form and evolve.) When leaders talk about building a strong and adaptive culture, they often forget they are not starting with a blank slate but with a rich mosaic of teams, units, groups of work buddies, and on and on, each with its own unique culture. Even if you serve as the CEO of Sphynx, Inc., you are only one of many culture CEOs finding ways to meet their particular needs. A culture never emerges solely from a mandate from on high. It grows out of the many tribes that inhabit every organization. To create a unified culture, you need to engage with others on their terms, approaching the task like an anthropologist exploring a new land, with a blank notebook and an open mind. In other words, to build a productive and prosperous culture, you must understand and care about all of the people who live and work in it.

Lesson #3: Culture changes. The natural world changes, societies change, people change. Why do some top-performing businesses with rock-solid cultures fall apart overnight? When you look at your own organization, why do terrific teams come together almost magically in one unit, while in another disgruntled groups seem to spring out of nowhere? Answer: all of the little cultures in your organization’s bigger culture constantly grow, evolve, and adapt to change. The moment you think everyone is finally moving in the same direction, something shifts, forcing you to rethink and rebuild your culture all over again.

Culture may at times seem like an out-of-control maverick with a mind of its own, but culture change follows principles as consistent as the planets and stars traveling across the sky. If you pay close attention, you will see the patterns emerge. We’ve spent decades looking for those patterns with the goal of helping leaders understand and harness them. Just as heavenly bodies follow the laws of physics, organizations follow the laws of cultural motion, propelled by forces that influence how we fulfill our needs and get things done together.

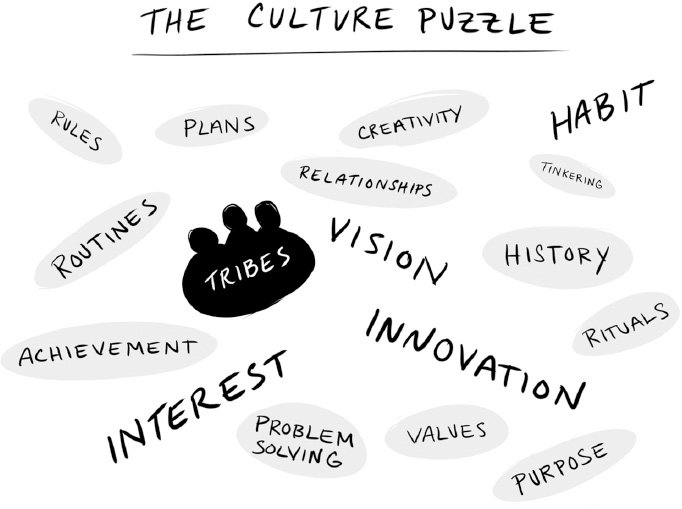

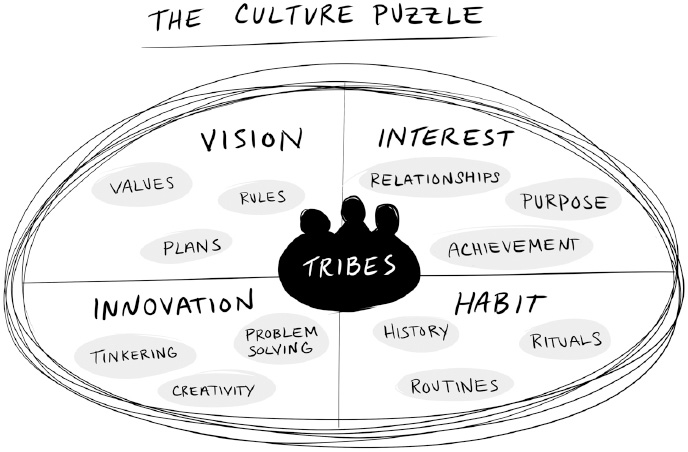

Four major forces drive culture: Vision, Interest, Habit, and Innovation. These forces have shaped every tribe, every organization, every nation, every society, and every civilization since the beginning of humanity. To build a strong culture, and bring your tribes together, you must harness all four forces and channel their collective energy toward supporting your organizational goals.

The Four Driving Forces

Vision. Every organization maintains a vision, communicated in mission and values statements, strategic plans, credos and mottoes, websites, speeches at town hall meetings, standard operating procedures, rules, and other means of broadcasting an organization’s culture. Vision tells the story of who you are as an organization and why you exist. Formal vision statements usually come from the top, but they mean nothing unless every member of an organization wholeheartedly embraces this larger story.

Interest. Everyone, as we have said, is motivated to fulfill basic needs for strong relationships, meaningful work, and dignity. Jobs that satisfy these needs fuel the drive to accomplish an organization’s vision. When people feel energized, they eagerly collaborate with colleagues, work hard to get results, and take great pride in belonging to an extended tribe.

Habit. In a strong sustainable culture, desired beliefs and behaviors become daily habits. What may have begun as a change initiative gradually becomes a shared routine, or “the way we do things around here.”

Innovation. While strong, productive cultures endure, they must constantly and quickly adapt to changes in the marketplace, the economy, and the competitive environment. Sometimes it even makes sense to borrow effective strategies from rivals. A tribe must maintain a delicate balance between continuity and the need to change and innovate in an increasingly chaotic modern world. That requires dedication to both vision and innovation.

The forces resemble pieces of a puzzle. (The endnotes review the extensive social science research that led us to a deeper understanding of the forces.) When you dump them onto a card table, they look like a random, confusing, headache-inducing mess.

But once you fit them together, you begin to see how they relate and interconnect. Now it all looks manageable.

Even at this early stage of your quest to solve the culture puzzle, you can begin assessing your organization, a prospective employer, one of your teams, or even a company whose stock you are thinking about buying. You can use the Culture Evaluator in the appendix to conduct a more complete assessment of your culture, but for now try answering these questions:

• Tribes. Does your organization operate primarily as one tribe, many tribes, or even competing ones? Does leadership do enough to create a feeling of unity among tribes? Do tribes collaborate with and support each other?

• Vision. Do people understand a clear set of values? Do they embrace the operating rules that support those values? Can they cite a credible, motivating plan that illuminates the path to a successful future?

• Interest. Do people across the organization fully engage with one another and their work? Do they feel they receive proper recognition for their work? Do people accomplish impressive goals and experience a sense of purpose as they do so?

• Habit. Do people follow individual habits and shared organizational routines that promote success? Does your organization use rituals to reinforce positive habits and routines?

• Innovation. Do people apply their utmost creativity to solving the biggest and most pressing problems? Are they always looking for ways to make incremental improvements? Do they take divergent viewpoints seriously? Are they open to new ways of doing things?

As you become more comfortable thinking in terms of the puzzle, the more you will realize its power to help you make smart and lasting cultural changes. Based on your initial reflection, where do you think you need to do the most work?

Knowing When to Go Fast and When to Go Slow

Culture is a timeless, distinctly human, collective process of learning and adaptation. For millennia, we humans have needed to solve problems related to our most basic needs and highest aspirations, creating an environment that strongly supports our efforts to learn and grow. Culture is the lifeblood of any group that lives and works together. The blood never stops circulating . . . until the group or organization disbands.

Here’s the puzzling thing: although culture defines organizations and even our humanity, most of us fail to see it clearly. But you can feel its effects everywhere. Even if you cannot get a firm handle on it, you can tell when it falters. Paying attention to the Four Forces model helps you understand what drives culture and see ways you might get it on track. It makes the abstract concrete.

What doomed Akhenaten’s big culture change? The people did not embrace his wild, new vision, which expressed his personal lust for power and gave scant attention to what mattered most in their humble lives. It did not satisfy their essential interests in getting their needs met. They quickly reverted to the old ways after Akhenaten died, failing to turn the new beliefs into habits. Given all of the other disconnects, it’s no surprise that they failed to draw on innovation to improve a deteriorating economy.

What caused WeWork to slip and fall from that high precipice? Neumann’s vision, for all of the rhetoric about community, proved to be an overhyped, idiosyncratic fantasy about his own greatness. The workspaces failed to resonate with the actual interests of the people who constituted the “we” in WeWork. Employees created their own set of habits that had little to do with the larger strategy. In the end, investors concluded the company’s business model lacked the true innovation needed to be sustainable.

Such cultural breakdowns happen all the time. Just consider all the high-profile businesses (Uber, Boeing, Wells Fargo, the Weinstein Company, to name a few) that engaged in stunningly bad, if not outright unethical, and even illegal behavior. It’s often so bad that journalists, regulators, politicians, and the general public lament the destructive effects of toxic cultures. When cultures implode, we always wonder, “What were those executives thinking?” Well, they weren’t thinking deeply enough about the culture puzzle.

Failing to think deeply about culture seldom stems solely from malice or greed. Yes, arrogant leaders might believe that societal norms and laws do not apply to them, but culture failures almost always trace their roots in part to simple inattention. So often we have heard: “We just need to hire the right people, initiate the right strategies, generate profit, and build our balance sheet, and our culture will take care of itself.” Sorry, but if you pay little attention to your culture, it will probably grow into one that disappoints and disempowers you. Though it often seems almost invisible, culture wields extraordinary power over the decisions you reach, the words you utter, the plans you form, and the actions you take.

We often compare the typical experience of culture to operating a plane on autopilot. We ride along without thinking about the controls (forces) that are keeping it in the air and speeding toward its destination. The Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls this the “fast mode.” We go along, doing whatever we’re doing (milking a cow, fastening a flange to a widget, running a Fortune 500 company), not fully aware of what we are doing or why. We decide to build a city in the desert, start a company that elevates human consciousness, or just make dinner, and then we barrel ahead into action.

Operating in the fast mode works fine in many situations:

• First, going fast helps us operate in a 24/7 business environment where competitors are plotting day and night to outperform us and stake a claim to our most valuable customers. It also serves us well as we move through a time-crunched Saturday afternoon, ticking items off our to-do list.

• Second, the fast mode does not require a lot of effort. It’s so much easier to react than reflect. You might like to picture yourself as Auguste Rodin’s statue The Thinker, with your brow furrowed as you contemplate Big Ideas, but, by the end of all that deep concentration, the pensive fellow was probably so worn out from taxing mental activity that he ended up with little energy to tackle something practical, like fixing a five-course gourmet dinner or even tying his shoes.

• Third, the fast mode obeys one of nature’s fundamental laws, the “conservation of energy.” A successful person saves enough energy to respond to all of the unexpected threats that pop up every day in life and business. Barack Obama wore the same gray and blue suits nearly every day of his presidency to conserve the valuable mental energy he needed to make big decisions affecting the world. Your day job may not directly impact the fate of nations, but all the little decisions required to get through a typical day can still make you less effective in the moments that matter.

The fast mode is a comfortable habit. Why tax our brains or strain our muscles when doing things the way we have always done them requires so little effort? Why take on the hard work of thinking deeply about and carefully assembling all those pesky pieces of the culture puzzle, when you can let culture take care of itself?

The famed psychologist William James developed a comprehensive “philosophy of habit.” His work on the subject has influenced many contemporary organizational experts, such as best-selling authors Jim Collins and Charles Duhigg. In a brief 1887 scientific study called Habit, James wrote, “When we look at living creatures from an outward point of view, one of the first things that strikes us is that they are bundles of habits. . . . Habit is thus the enormous fly-wheel of society.”

When you harness that flywheel of habit in the service of basic human needs—when, even better, you harness all of the Four Forces to serve those needs—you will energize your organization and propel it to world-class status. In this chapter, we have shared examples where the opposite happened. In later chapters, however, we will tell many stories about organizations that solved the culture puzzle, assembling all of the pieces into a satisfying, harmonious whole.

The success stories follow a similar plotline. A keen observer realizes their culture needs to shift. They take time to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the current culture before they introduce any big changes. In other words, they go slow before they go fast. To slow down, they imitate the best aspects of The Thinker, putting their chin in their hand and taking the time to reflect, but they never withdraw. In fact, going slow often also means engaging more actively and probing every part of an organization, for as long as it takes, to understand the current culture. Before making a list of any new habits they want others to develop, they pinpoint the old habits that are stalling progress toward results. It’s not easy. We all naturally prefer to stay in our comfort zones. But it takes time and effort to build the good habits that breed success. Our research into corporate failures reveals that all too many of them occurred because their leaders thought themselves so infallible that they could turn any vision, even a cockeyed one, into a virtual religion.

Elizabeth Holmes offers an excellent case in point. Like Neumann, she won initial accolades as a visionary genius. Her biotech company Theranos achieved a valuation of $9 billion because investors believed her claims that the company’s automated blood testing devices would revolutionize medicine by using minute amounts of blood for quick diagnoses. In 2015, Forbes named Holmes the youngest and wealthiest self-made female billionaire in America. But her perch atop the pyramid did not last long. In 2015, claims that she had defrauded investors and government regulators made headlines, and, in June 2018, a federal grand jury indicted Holmes and her lover, former Theranos chief operating officer Ramesh Balwani, on nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud for distributing blood tests with falsified results to consumers. By 2020, Holmes’s net worth had plunged to approximately zero.

According to the Wall Street Journal’s John Carreyrou, even as the claims of fraud made headlines, Holmes announced to remaining employees that “she was building a religion.” Balwani went further, insisting that anyone who was unwilling to “show complete devotion” to the cause should “get the (expletive) out.”

What were they thinking?

You know the answer already. They were going too fast to think much at all. It’s only natural to avoid expending the energy required to switch modes from fast to slow and really pay attention, but there are times when your future and even survival depend on it. To achieve your greatest ambitions (whether you are launching a start-up, serve as CEO of a Fortune 100 company, have just won the election for mayor of your town, lead an intramural basketball team, hope one day that the Museum of Modern Art will hang one of your paintings on its wall, or simply want to do a good job as a parent, friend, or someone’s significant other), you must, from time to time, flip the switch from fast to slow and pause to listen deeply to others and discover what they need. When you listen, you hear about the positive aspects of a culture that should be kept. You also learn about the parts that, like Akhenaten’s decrees, are best left in the ash heap of your organization’s history.

WHAT IS CULTURE?

Culture . . .

• Emerges from the interaction of the Four Forces

• Guides ways of thinking, behaving, valuing, and communicating

• Produces collective accomplishments

• Forms groups and promotes a feeling of belonging

• Changes ceaselessly

As the novelist George Orwell put it, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant effort.”

Capturing the Hearts and Minds of the People

Let’s take a closer look at what went wrong with Pharaoh Akhenaten’s attempt to shift Egypt’s culture. Marsha Hill, a curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, summed up history’s verdict: “Everybody likes revolutionaries at some level. Someone who has a real, good strong idea that makes it seem like things are going to get better. Of course, it didn’t work out.”

Akhenaten went fast, moving quickly and systematically to replace long-standing religious practices, myths, and symbols. He also introduced a blitzkrieg of innovations in language, architecture, and policy. Yet even as his people outwardly conformed to these massive changes, they protected the old beliefs that were deeply engraved in their hearts and minds. They secretly hid away figurines of the traditional gods and molds for casting amulets in their likeness.

Pharaoh remained oblivious to what his people really thought about him and his Sun God dreams. Limestone reliefs housed in Berlin’s Neues Museum depict tender domestic scenes of Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti snuggling with their children, but historians know now that the people’s attitude toward the family was harsh and unforgiving. According to the archaeologist Anna Stevens, “For most people, life was tough, with hard labor and a basic diet.” More than two-thirds of the population died before age 35. Stevens speculates that they were literally “worked to death.” Children suffered as well. Archaeological evidence shows widespread malnutrition among the younger generation.

Once again, we see how arrogance and a refusal to see what’s right in front of your nose produce stunning disconnects. Stevens notes that the tombs of senior officials contain detailed images of the royal family, while such homages never appear in the cemeteries of the common people. “There’s no mention of Akhenaten or Nefertiti. It’s like it’s not their place. You can have very radical changes at the top, but below that, nothing changes.”

While a culture change often springs from the collective mind of the C-suite, it will not take hold throughout an organization unless it captures hearts and minds. According to a recent study published in the Harvard Business Review, CEOs and CHROs (chief human resource officers) identify “managing and improving the culture” as their top priority for talent development, yet most contemporary workers do not see the effects of that belief. They hear the words, but they do not take them to heart:

• 87 percent of employees don’t understand the goals that come from top management.

• 69 percent don’t believe in the goals (if, in fact, they do understand the goals).

• 90 percent don’t behave in ways that reflect the goals.

A PricewaterhouseCoopers study confirms these disheartening statistics, finding that less than a third of workers feel connected to their company’s purpose and that over half feel less than “somewhat” excited about their jobs. Bottom line: there’s a serious disconnect between what leaders say and what their people think and feel about what they say. That gap explains a lot of the underperformance many organizations suffer today.

The pieces of the culture puzzle begin to fall into place when you realize that a vision must capture everyone’s imagination. The people may publicly bow to a leader who announces the latest Big Change, but if they resist buying into it, they will not devote their best efforts to the cause and will even sabotage it behind the scenes. Culture change does not work if people only pay lip service to new beliefs and behaviors. It has to go deeper, much deeper. Given that, it’s not surprising that it often feels like an impossible-to-implement process that can only end in frustration. “Can’t people just get it?” you cry. “Why do productivity and profitability keep sagging despite all of the time and effort we have put into this campaign to do things differently?”

Well, we would answer those questions without missing a beat: you need to harness the Four Forces (vision, interest, habit, and innovation) to create a new culture. When you tap into them, you will assemble a culture that sustains a whole new way of doing things. Just as important, the tenets of the new culture must keep evolving to meet new challenges in the business environment. To come alive, it has to keep endlessly moving, adapting, and growing. When that happens, you can flip back to the fast mode and, at least for a while, let the enterprise cruise on autopilot. At the same time, you must prepare yourself to go slow again if the culture needs an adjustment or a major overhaul. At those times, you must switch off autopilot and do the hard work of paying attention to what’s right in front of your nose.

Mastering the Art of Envisioning, Listening, Reflecting, and Experimenting

We admit our Four Forces Model is deceptively simple. It streamlines a highly complex process. We could write a long book about each of the puzzle pieces, with such titles as Managing Relationships, Getting Things Done, Taking Performance to the Next Level, Creating the Perfect Mission Statement, Engaging Your Workforce, Making Success a Habit, and Mastering the Art of Innovation. But those weighty tomes would not tell you how to put all of it together. That’s why we picture culture as a puzzle. It’s not one or two things; it’s everything. Our model shows you how to build, change, or refresh your culture, assembling it piece by piece. In later chapters, we will go deeper into the steps you can take to manage each of the Four Forces:

Harnessing the Four Forces to Create a Winning Culture

1. Envision. Engage vision to imagine your desired culture in the clearest, most concise, and most compelling terms. Begin thinking in terms of vivid language and stories that will capture hearts and minds. (Chapter Four)

2. Listen. Tune in to the power of interest by slowing down and paying attention to the stories your people tell about their deepest social and emotional needs. Begin forming strategies to close the gap between what they need and what your organization delivers. (Chapter Five)

3. Reflect. Facilitate a constructive dialogue with everyone in the organization about aligning the desired culture with people’s needs in order to create new habits. Think carefully about creating rituals that celebrate those habits. Look outside your walls for ideas about how to get results, searching for opportunities to learn from other companies, including your competitors. (Chapter Six)

4. Experiment. Organize and launch innovative small- scale projects designed to close the gaps you have identified between what people need and what they actually gain from your organization. Feel free to stretch a bit with some of the projects. Think outside the lines and boxes on the org chart. Carefully assess what works and what doesn’t work in order to manage the controlled chaos of innovation. (Chapter Seven)

Entrepreneurs Neil Blumenthal and David Gilboa followed these steps when they created the culture that drives the eyewear company Warby Parker. While still working toward their MBAs at the Wharton School, they started a little four-person, web-based company that in a relatively short time grew into a large and highly profitable global brand. The company began with a simple but compelling vision: providing quality eyeglasses for those who can barely afford them. They listened not only to what their prospective customers needed but also to what their employees sought in terms of fulfilling work. They reflected with those employees on how the socially conscious vision aligned with how work actually got done day to day at Warby Parker. They experimented with ways to operationalize their vision and create a thriving business. Less than a decade after its founding, the company had achieved “unicorn” status (i.e., a $1B valuation). Reflecting on the company’s success, Gilboa said, “[Customers] saw that we tried to make them happy. With 2000 employees now, that’s a lesson we continue to practice in our corporate culture.” Blumenthal and Gilboa understand that any solution to the culture puzzle must respect the need for the distinctly human happiness inspired by helping others.

Sustainable business cultures embody human values. Billionaire Yvon Chouinard, founder of the outdoor clothing business Patagonia, emphasized this fact when he wrote in his book Let My People Go Surfing:

Work had to be enjoyable on a daily basis. We all had to come to work on the balls of our feet and go up the stairs two steps at a time. We needed to be surrounded by friends who could dress whatever way they wanted, even be barefoot. We all needed to have flextime to surf the waves when they were good, or ski the powder after a big snowstorm, or stay home and take care of a sick child.

Does your company satisfy the needs of your people and those to whom they provide products and services? If you feel unsure about your answer, do not despair. You can harness the Four Forces to energize your organization and fulfill its highest purpose.

“Wait a second,” you might say. “I’m not in charge, and in fact I’m stuck with a bunch of dictatorial Sun Gods who dismiss all this soft stuff about culture.” We hear that all the time. But wherever you sit in your organization, on the top floor in the C-suite or buried downstairs in the billing department, you can take steps to turn around the culture. If you begin to see how the Four Forces move ceaselessly through every single encounter, conversation, and decision, you can target those moments where even the smallest effort can make a difference. Sun Gods issue sweeping orders to their minions, but even a powerful king cannot order a culture to get in line. Unlike Sun Gods, gardeners design and cultivate a culture the way they nurture lush vegetation. If you want to make changes happen, concentrate on influencing the forces that shape your garden. In the following chapters, you will learn how people in many different roles have successfully created healthier, more productive working environments. Many toil away far from the corner office.

Taking Care of Business, Taking Care of People

Lee Nunery received a surprising late-night phone call on March 14, 2001. “I’ll never forget that date,” he said later. A few hours earlier, Nunery had buried his wife, Carolyn, who had died from Stage IV lung cancer. At home in a Philadelphia suburb, not long after he had put his kids to bed, his cell phone rang. Who, he wondered, could be calling at this time, of all days?

“Lee,” the caller announced, “this is David Stern.”

Since 1999, Nunery had directed Business Services at the University of Pennsylvania, but he had previously worked for Stern, the commissioner of the National Basketball Association (NBA). At first, he thought the call was a hoax. He had not spoken with Stern for many years.

“Don’t (expletive) with me, you (expletive),” he shouted into the phone.

“No, Lee,” replied the voice at the other end of the line. “This is really David.” He was calling to offer condolences to his former employee and colleague.

David J. Stern is best remembered as the man who turned around the moribund NBA. While in 2020 the league employed thousands of people and boasted a total valuation of $60 billion, in the early 1980s just a few dozen full-time employees worked for an organization that made barely any money. The Championship Finals attracted so little interest that CBS broadcast the games on tape-delay late at night. Stern came aboard in 1984 with a mandate to steer the ailing enterprise toward growth and profitability. He immediately made two key decisions: he imposed a salary cap on teams and established a mandatory drug- testing program.

Stern had earned a reputation as a demanding, detail-oriented, and even dictatorial boss. Nunery learned from firsthand experience that Stern deserved that reputation. As Nunery recalled, “I’d bring him a two-hundred-page report that I had sweated blood over. He’d give it a quick skim while I was sitting in his office, notice a misplaced comma, and go ballistic. He’d still be screaming when I walked out the door.” But Nunery also saw greatness in Stern. “In terms of brilliance, David was that. I had never met anyone as studious. He could see around corners, ‘spotting issues’ as he called it. He saw things other people weren’t seeing.”

Stern applied his detail orientation not only to business but to connecting with people, a trait that explains his late-night call to Nunery. “He reached out to everybody he knew.”

According to Nunery, the Hall of Famer Magic Johnson felt the same way. At the memorial service held after Stern’s death in January 2020, Johnson said, “This man stood up for me when everyone else was running away.” In November 1991, when Johnson announced at a Los Angeles press conference that he was HIV positive, the general public worried that someone could contract AIDS through something as casual as a handshake. Stern helped “change the world,” as Johnson put it, by allowing him to play in the NBA All-Star Game and on the Olympic Dream Team just months after the announcement.

Accomplishing that world-changing mission would require the support of key members of the organization. As Nunery tells the story, Stern told Johnson, “I want you to play on the Dream Team, but you have to convince [Michael] Jordan and [Larry] Bird to play too.” In his mind, it all depended on people doing the right thing with the right people. It also involved give-and-take. That bedrock truth holds true for all great cultures.

Stern appreciated that creating a successful, results-driven business culture involved discovering and respecting the needs of others and instilling that trait in everyone associated with the organization. He pushed people hard, down to the last comma. But he treated them like family too. Looking back on the years spent working for his tough boss, Nunery observed, “He was invested in the stories of the people around him, because the stories say a lot about how people are going to react. He wanted to get to your heart.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• Start thinking about how to assemble your culture puzzle.

• Know when to go fast and when to go slow.

• Capture hearts and minds.

• To change a culture, harness the Four Forces.

• Take care of people, and they will take care of business.