Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Tom Szaky sets out to do the impossible – eliminate all waste. This book paints a future of a “circular economy” that relies on responsible reuse and recycling to propel the world towards eradicating overconsumption and waste.

Only 35 percent of the 240 million metric tons of waste generated in the United States alone gets recycled, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. This extraordinary collection shows how manufacturers can move from a one-way take-make-waste economy that is burying the world in waste to a circular, make-use-recycle economy.

Steered by Tom Szaky, recycling pioneer, eco-capitalist, and founder and CEO of TerraCycle, each chapter is coauthored by an expert in his or her field. From the distinct perspectives of government leaders, consumer packaged goods companies, waste management firms, and more, the book explores current issues of production and consumption, practical steps for improving packaging and reducing waste today, and big ideas and concepts that can be carried forward.

Intended to help every business from a small start-up to a large established consumer product company, this book serves as a source of knowledge and inspiration. The message from these pioneers is not to scale back but to innovate upward. They offer nothing less than a guide to designing ourselves out of waste and into abundance.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Tom Szaky sets out to do the impossible – eliminate all waste. This book paints a future of a “circular economy” that relies on responsible reuse and recycling to propel the world towards eradicating overconsumption and waste.

Only 35 percent of the 240 million metric tons of waste generated in the United States alone gets recycled, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. This extraordinary collection shows how manufacturers can move from a one-way take-make-waste economy that is burying the world in waste to a circular, make-use-recycle economy.

Steered by Tom Szaky, recycling pioneer, eco-capitalist, and founder and CEO of TerraCycle, each chapter is coauthored by an expert in his or her field. From the distinct perspectives of government leaders, consumer packaged goods companies, waste management firms, and more, the book explores current issues of production and consumption, practical steps for improving packaging and reducing waste today, and big ideas and concepts that can be carried forward.

Intended to help every business from a small start-up to a large established consumer product company, this book serves as a source of knowledge and inspiration. The message from these pioneers is not to scale back but to innovate upward. They offer nothing less than a guide to designing ourselves out of waste and into abundance.

“Plastics came of age in the 1950s, changing manufacturing forever. By telling the story that leads us to today's linear packaging model, I illustrate that designing into the circular systems that came before it can be a short journey back.”

— Attila Turos, former Lead, Future of Production Initiative, World Economic Forum

“In The Future of Packaging, we talk about the modern problem of waste, how packaging fits into that, and how we can design out of it. It is important to explain the forces that catalyzed the first formal recycling programs in the United States, defining the need to scale up on today's systems.”

— Christine “Christie” Todd Whitman, President, The Whitman Strategy Group; former Governor of New Jersey; and former administrator, Environmental Protection Agency

“Moving away from the linear take-make-waste model is an ethical imperative. In my chapter, I talk about the fragmented global recycling system and how investing in it presents opportunity for innovation, jobs creation, education, and, above all, prosperity.”

— Jean-Marc Boursier, Group Senior Executive Vice President, Finance and Recycling & Recovery (Northern Europe), SUEZ

“Whether you are a packaging manufacturer, small business, local government, or consumer, this book will transform the issues we've avoided into ones we are motivated to tackle head-on. My chapter calls for a paradigm shift in producer responsibility, placing waste and materials management in the hands of the producer as an asset, not a burden.”

— Scott Cassel, founder and CEO, Product Stewardship Institute

"Almost everything is technically recyclable, so why do we have so much waste? Improving our recycling system will help us turn more waste into worth. When we view recycling in terms of supply and demand, it is much easier to see where system advancements are needed. We hope The Future of Packaging brings this to life and shows how each of us can do our part to keep our environment and oceans free from litter.”

— Stephen Sikra, Associate Director, Corporate R&D, The Procter & Gamble Company

“Nearly every packaging ‘innovation' that has made products lighter, less expensive, and more convenient can't be recycled through public programs . . . and is thrown away after one use. In this book, we deep dive into the lightweighting trend and ways to maximize value for packages through design.”

— Vice President, Environmental Sustainability, Europe & Sub Saharan Africa, PepsiCo

“Packaging can be an important ally to help prevent waste, even for high-end products that often use excessive or nonrecyclable materials. My chapter has tips to help designers create premium yet sustainable packages—along with examples of brands that got it ‘just right.'”

— Lisa McTigue Pierce, Executive Editor, Packaging Digest

“Packaging design isn't just about the package but the processes associated with manufacturing, transporting, and distributing it. In this book, I bring the often-unseen preconsumer waste stream to light.”

— Tony Dunnage, Group Director, Manufacturing Sustainability, Unilever

“The Future of Packaging: From Linear to Circular is today's handbook for designing out of a world that feeds people a skewed version of what they need to be prosperous and brands a narrow view of what they can do to be profitable . . . Consumers care about where their products come from and what happens after they are done with them. Brands and designers need to pay attention.”

— KoAnn Vikoren Skrzyniarz, founder and CEO, Sustainable Life Media and Sustainable Brands

“Consumers reward brands that make the responsible choice the easy one . . . Brands must today ask themselves, ‘How do we enable responsible consumption?' The Future of Packaging is a resource for companies doing this heavy lifting.”

— Virginie Helias, Vice President, Global Sustainability, Procter & Gamble

“Leading the change you wish to see in your company can be challenging. The Future of Packaging contains practical models and powerful examples to champion sustainable programs. In my chapter, I take you through how we stewarded circular initiatives at Procter & Gamble and my insights for applying these at a company of any size.”

— Lisa Jennings, Vice President, Global Hair Acceleration, Procter & Gamble

CHAPTER 1

Plastic, Packaging, and the Linear Economy

Attila Turos

Former Lead, Future of Production

Initiative, World Economic Forum

IMAGINING A WORLD WITHOUT PLASTIC IS NEARLY IMPOSsible. We interact with it from the moment our digital clocks, smartphones, smart speakers, and Wi-Fi-enabled coffee makers wake us up, to the time we sleep on memory foam mattresses and microfiber sheets. Paper coffee cups are lined with it, razor blades are now forged of it, and lifesaving medicines and treatments are administered and delivered by it in more configurations than ever before. Industries once dominated by metal and other naturally occurring materials (like wood and cotton) have been taken over by plastic, which now makes up roughly 15 percent of the average car by weight and about 50 percent of jets like the Boeing Dreamliner.1

Consumers are often surprised to learn just how pervasive plastic is across the entire economy. The corkboard you have hanging on your wall? Cork-colored plastic. Your kid’s synthetic fur plush toys and stuffed animals? Plastic. The core of your “wood” door is made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and insulating plastic foam. The textiles of nearly every item in most of our closets are majority oil-based fiber, and very few of us are actually “burning rubber” with our vehicles when we speed off to our next appointment.

Business is largely responsible for this shift. In fact, one of the first man-made plastics was the result of a commission to find an alternative material for school blackboards in the late 1800s,2 an anecdote illustrative of industry’s close ties to the development of plastic as the favored medium for business. Items once carved out of a solid block of wood, forged of steel, or spun out of wool can be more easily made from plastic, which is lighter, stronger, and less expensive to produce, an aspect that has numerous functional, aesthetic, and economic advantages for both companies and consumers.

Modern life now is dependent on the fossil fuel by-product, as the American Petroleum Institute’s 2017 “Power Past Impossible” Super Bowl ad reminded the public.3 The ad shows a robotic prosthesis pulling an arrow firmly back in a bow to reveal itself attached to a young woman. High-contrast blue and magenta of an electrocardiogram displays the beat of an artificial but fully pumping heart valve. An image of a rocky golden landscape is reflected in the helmet of an astronaut who, backlit by fog and sparks, walks away from us, with a pack sporting a decal of the American flag.

A Material of Substance

The spirit of these forward-thinking innovations can be traced back to the discovery and inspired use of natural, bioderived substances such as rubber, egg, and blood proteins by ancient artisans and craftsman (manufacturers in their own right) as early as 1600 BCE.4 Cutting-edge for their time, the useful behavior of these plasticlike compounds sealed the roofs of dwellings, made containers and pots, and banded goods together for transport, offering an alternative construction material for the business activities of early humans. Since then, plastics have evolved into myriad man-made material types,5 poised to address changing needs, as well as gaps, in a competitive market.

Synthetic polymers have been disrupting commodity industries for well over 100 years. John Wesley Hyatt patented Celluloid in 1869,6 a commercially viable solid, stable nitrocellulose used to make things like billiard balls, false teeth, combs, jewelry, and piano keys; it had a comparable performance and look, a more secure supply chain, and a much better price point than the more expensive conventional materials. Celluloid could be rendered to resemble ivory, tortoiseshell, marble, ebony, and semiprecious stones. Interestingly, Hyatt’s company boasted in one pamphlet, “It will no longer be necessary to ransack the earth in pursuit of substances which are constantly growing scarcer.”7

Then in 1907 Leo H. Baekeland, called “the Father of the Plastics Industry,” developed Bakelite, the world’s first synthetic, durable plastic.8 Solid and sturdy, it was a favored material for high-value products like radios, telephones, toys, and game pieces; later it was used for wartime equipment such as pilots’ goggles and some parts of firearms well into the 1940s. By then the improvements in chemical technologies that burgeoned in World War I were combined with the leaps in mass production made in WWII, setting the stage for the modern economy of plastics we see today.

Plastic Fantastic

It was this moment, when plastic went from being a prototype, premium material to a viable, cost-effective mode of producing consumer products, that manufacturers’ uses for it became limitless. Injection-molding machines turned raw plastic powders or pellets into a molded, finished product in a one-shot process. A single machine equipped with a mold containing multiple cavities could pop out 10 fully formed products, like combs or flooring sheets, in less than a minute.

Coming out of wartime, output quotas long dedicated to government and the military machine were suddenly freed up for a plastics industry poised to break into an untapped market: civilians. After the war, according to one executive, “virtually nothing was made of plastic and anything could be.” Soon synthetics factories were churning out Tupperware, Formica tables, polyester fast fashion, lifesaving Kevlar vests, and new toys like hula hoops, Legos, and Barbie. By 1960 plastics had surpassed aluminum, becoming one of the largest industries in the United States; in 1969 Neil Armstrong planted a nylon flag on the moon.9

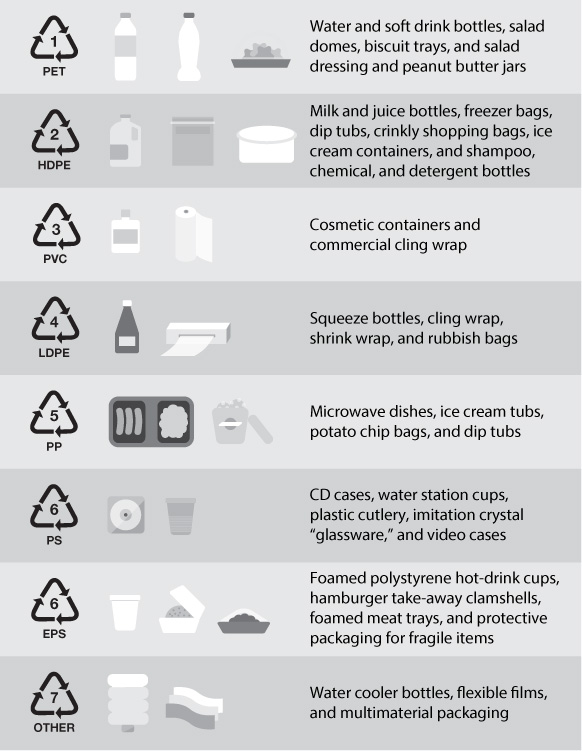

Plastic has been the key enabler for sectors as diverse as packaging, construction, transportation, health care, and electronics. It’s a simple way to mass-produce goods that once needed to be carved, welded, or blown out of heavier, more laborious material. Plastic packing and packaging material allows delicate items like food, medicine, and clothing farther distribution and easier handling. Polymers give body to common household items like insulation, piping, putty, and paint. Plastic increases consumer access to products and services both literally and financially, driving consumption. Innovation thrives with it, as industry has come to depend on it. SEE 1.1

1.1 This table of main resin types, categorized by numbers 1 through 7, illustrates the pervasiveness of plastic in the modern economy.

World Economic Forum

The challenges of decoupling plastic from production and innovation as we know it would be eclipsed only by consumers trying to live without it. Today nearly everyone comes into contact with plastics, especially plastic packaging—its largest application, representing 26 percent of the total volume of plastics used.10

Plastic and the Linear Economy

While delivering many benefits, the current plastics economy has drawbacks that are becoming more apparent by the day. For instance, with more than 280 million metric tons of new, virgin plastic produced globally per year,11 only 14 percent of all plastic packaging is collected for recycling. When additional value losses in sorting and reprocessing are factored in, only 5 percent of the material value of what we often use only once— single-use plastics—is retained for the next time around.

Plastic recycling has not kept pace with the continued demand for plastic production, which would be offset by the capture of more of this discarded material. And the problem is growing: today we produce 20 times more plastic than we did in 1964, and that volume is expected to double again in the next 20 years—and almost quadruple by 2050, the same year that plastics will outweigh fish in the world’s oceans.

Nearly every product and packaging innovation has been brought into modernity with materials and designs that global recycling systems cannot handle, and consumer products companies are producing more materials that end up in landfills than ever before. Circular systems of reuse—vesting products with value and striving to keep them at high utility—have fallen in favor of largely linear ones that, despite the sophisticated science and technology behind them, view products and packaging as disposable, or designed to be thrown away.

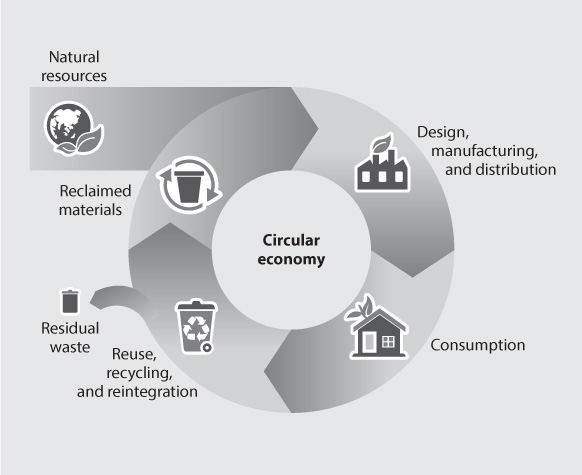

Simply Circular

It wasn’t always like this. Products and packaging used to cycle through a more regenerative circular economy, where, as in nature, things didn’t go to waste. In contrast to the linear economy, this make-use-recycle-remanufacture concept creates value at each stage of a product’s circular life cycle as recovered materials are returned to productive use. Here it is important to remember that waste in itself is a relatively modern idea that came about when it became more economically viable to produce new materials than to repurpose existing ones—and to burn and bury the rest. Up until the 1940s, when mass production, shifts in consumerism, and plastics came into play, things were actually quite circular. SEE 1.2

Dairy distributors provided reusable glass bottles that customers could empty and then leave on their doorsteps in the cultural motif we know as “the milkman.” These glass bottles, which flowed through a system in which the producer was responsible for them (and owned them as an asset), had a high rate of reuse. So did durable containers provided by consumers for producers to fill with their purchases of other consumables such as oil, eggs, and cream.

What consumers didn’t have delivered, they would shop for, and buying groceries and household items worked in the same way: either the patron or the producer provided reusable containers and wraps that could be returned, cleaned, and used again for the next batch. The concept of dual-use packaging, structurally designed to serve a function after first product use, got products off shelves by giving consumers “more for their money”; examples are condiments sold in decorative crocks and dry goods sold in reusable cloth bags or tin canisters. An emerging consumer culture encouraged more buying and selling, so producers sold “two products for the price of one,” innovations of marketing and design that carried well through the Great Depression and far into the 1960s.

1.2 It was once intuitive that materials, resources, and products should reused, repaired, and recycled in what we call the circular economy.

European Commission

But companies eventually realized that sales need not be contingent on the flow of reusable containers. So, to make products easier to buy, use, and be needed again, they adopted packaging that took what couldn’t be placed unwrapped in a cart, basket, or pack and made it marketable and easier and cheaper to buy.

Single-Use Packaging

Lighter and more portable than thick refillable glass bottles, commercial metal cans and tins used to store and preserve food (a revolution that afforded larger mobilization of armies, longer product lives, and massive reductions of the burden on supply chains) entered into production in the 1800s. Introduction of the beer can in 1935 got the ball rolling in terms of a viable way to mass-package and distribute beverages. The invention of the pull-tab in 1959 revolutionized the metal can as a convenient, lightweight vessel for beverages, with high function and recyclability (when recyclability was more of a priority, of course).

In 1915 the concept of carton-based packaging offered a lighter, paper-centric alternative to glass and metal. The patent on the first “paper bottle,” called the “Pure-Pak,”12 featured a folding paper box for holding milk that could be glued and sealed at a dairy farm for distribution. While the paper of traditional gable-top cartons could be reclaimed, today’s carton technologies feature various combinations of plastic, metal, and paper; moisture barriers; and rigid plastic closures and fitments for function and convenience that are generally not recyclable. SEE 1.3

It’s these highly affordable, single-purpose, self-service models of packaging that began to change inherently circular systems into linear ones. Over time people’s expectations and habits were shifting from reusing containers to throwing them in the garbage. Extending product shelf life and making it easy for people to simply buy milk in its own container whenever they wanted, these configurations would give way to mass production and distribution, as well as the expansion of the general store to the supermarket to finally the quarter-million-square-foot big-box stores we enjoy today.

1.3 The milk container as evolved from delivery in reusable glass bottles (distributed from large aluminum cans), to the single-use paper carton, the plastic bottle, and the shelf-stable, multi-compositional, and largely unrecyclable aseptic cartons and pouches of today.

h2ozoe/kericanfly/Pack/Shutterstock

Then, of course, came plastic. The use of plastic to package foods and beverages went from being an expensive technology to an affordable, economically viable practice when high-density polyethylene (HDPE, or #2 plastics) was introduced; in the wake of World War II, plastic production in the United States increased by 300 percent.13 Compared with glass bottles, plastic’s lightweight nature, relatively low production and transportation costs, and resistance to breakage made it popular with manufacturers and customers.

Durable, Long-Lasting—and Disposable?

Today the food-and-beverage industry has almost completely replaced glass bottles with plastic ones. In 2016 almost half a trillion PET bottles were produced, up from about 300 billion a decade ago, with continued growth in the forecast.14 The demand, equivalent to about 20,000 bottles being bought every second, will increase to nearly 600 billion by 2021, according to the most up-to-date estimates from Euromonitor International’s global packaging trends report.15 Despite these projections, most of the plastic bottles produced today end up in the garbage.

Four categories of plastic packaging are tracked for linear disposal:

Small-format packaging includes sachets, tear-offs (the thin plastic films on food containers), lids, straws, candy wrappers, and small pots (such as cosmetics containers) that tend to escape collection and sorting systems and have no economic reuse or recycling pathway. Small-format packaging represents about 10 percent of the market by weight and 35 percent to 50 percent by number of items.

Small-format packaging includes sachets, tear-offs (the thin plastic films on food containers), lids, straws, candy wrappers, and small pots (such as cosmetics containers) that tend to escape collection and sorting systems and have no economic reuse or recycling pathway. Small-format packaging represents about 10 percent of the market by weight and 35 percent to 50 percent by number of items.

Multimaterial hybrid packaging currently cannot be economically recycled; these include stand-up food pouches and aseptic cartons. By combining the properties of materials, multimaterial packaging can often offer enhanced performance versus its monomaterial alternatives, such as providing oxygen and moisture barriers at reduced weight and costs. Multimaterial hybrids represent about 13 percent of the market by weight.

Multimaterial hybrid packaging currently cannot be economically recycled; these include stand-up food pouches and aseptic cartons. By combining the properties of materials, multimaterial packaging can often offer enhanced performance versus its monomaterial alternatives, such as providing oxygen and moisture barriers at reduced weight and costs. Multimaterial hybrids represent about 13 percent of the market by weight.

Uncommon plastic packaging materials, while often technically recyclable, are not economically viable to sort and recycle because their small volume prevents effective economies of scale; these include PVC, polystyrene (PS, or #6 plastics), and expanded polystyrene (EPS, also known as Styrofoam). Uncommon plastics represent about 10 percent of the market by weight.

Uncommon plastic packaging materials, while often technically recyclable, are not economically viable to sort and recycle because their small volume prevents effective economies of scale; these include PVC, polystyrene (PS, or #6 plastics), and expanded polystyrene (EPS, also known as Styrofoam). Uncommon plastics represent about 10 percent of the market by weight.

Nutrient-contaminated materials, from dining disposables to coffee capsules, are often difficult to sort and clean for high-quality recycling. This segment includes applications and configurations that are prone to be mixed with organic contents during or after use.

Nutrient-contaminated materials, from dining disposables to coffee capsules, are often difficult to sort and clean for high-quality recycling. This segment includes applications and configurations that are prone to be mixed with organic contents during or after use.

Instead of milk bottles, we now have milk bags. Instead of getting our soda in refillable glass bottles or recyclable aluminum cans, we buy a plastic bottle to take with us to eventually toss. Every step on this progression has brought with it less and less recyclable packaging; the recyclability of each of these packages is effectively halved with every step, with all flexible packaging being completely nonrecyclable.

The Role of Business in the Circular Economy

Industries and businesses (and, in part, the consumers who demand it and the governments that allow it) have driven the shift away from the naturally circular patterns of yesteryear. Thus companies and major brands are the ones in a position to compel the change forward toward more regenerative business practices. Although the global recycling infrastructure is inefficient and the world economy continues to view material as useless after one use, there is opportunity to capitalize on these gaps in the same way that plastic revolutionized production and continues to drive consumption in the first place.

Brands, governments, celebrities, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are today promoting a host of innovations that provide real solutions to the plastics problem. Reusable packaging is part of the answer, but designing a plastics reclamation system that works and reinventing the types of plastic packaging that make technologies possible but almost never get captured are objects of our search. Recent New Plastics Economy Innovation Prize winners included a compostable multilayer material from agricultural and forestry by-products (perfect for food packaging) and a magnetic additive that can be used in lieu of foils in moisture barrier technologies in aseptic cartons and pouches for a fully recyclable package.16

Calling for an end to the current single-use plastic– reliant product economy—despite mounting knowledge of the environmental and social justice issues we know plastics to pre sent—is much, much easier said than done. So instead of simply setting out to change what we produce and consume through design, we must strive to also change the way we participate in the product economy.

There are endless opportunities to establish circular systems where they currently do not exist and to strengthen them where the groundwork has been laid. These are the practices that will differentiate you from your competitors and prepare you for resilience and growth in an uncertain future.