Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Influential Product Manager

How to Lead and Launch Successful Technology Products

Ken Sandy (Author)

Publication date: 11/21/2019

Product management is one of the fastest growing and most sought-after roles by job seekers and companies alike. The availability of trained and experienced talent can barely keep up with the accelerating demand for new and improved technology products. People from nontechnical and technical backgrounds alike are eager to master this exciting new role.

The Influential Product Manager teaches product managers how to behave at each stage of the product life cycle to achieve the best outcome for the customer. Product managers are under pressure to drive spectacular results, often without wielding much direct power or authority. If you don't know how to influence people at all levels of the organization, how will you create the best possible product?

This comprehensive entry-level textbook distills over twenty years of hard-won field experience and industry knowledge into lessons that will empower new product managers to act like pros right out of the gate. With teaching experience both from UC Berkeley and Lynda.com, the author boils down the most complex topics into principles that are easy to memorize and apply.

This book methodically documents the tools product managers everywhere use to align their teams with market needs and organizational goals. From setting priorities to capturing requirements to navigating trade-offs, this book makes it easy. Not only will your product succeed, you'll succeed, too, when you read the final chapter on advancing your career. Let your product's success become your success!

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Product management is one of the fastest growing and most sought-after roles by job seekers and companies alike. The availability of trained and experienced talent can barely keep up with the accelerating demand for new and improved technology products. People from nontechnical and technical backgrounds alike are eager to master this exciting new role.

The Influential Product Manager teaches product managers how to behave at each stage of the product life cycle to achieve the best outcome for the customer. Product managers are under pressure to drive spectacular results, often without wielding much direct power or authority. If you don't know how to influence people at all levels of the organization, how will you create the best possible product?

This comprehensive entry-level textbook distills over twenty years of hard-won field experience and industry knowledge into lessons that will empower new product managers to act like pros right out of the gate. With teaching experience both from UC Berkeley and Lynda.com, the author boils down the most complex topics into principles that are easy to memorize and apply.

This book methodically documents the tools product managers everywhere use to align their teams with market needs and organizational goals. From setting priorities to capturing requirements to navigating trade-offs, this book makes it easy. Not only will your product succeed, you'll succeed, too, when you read the final chapter on advancing your career. Let your product's success become your success!

Ken Sandy has worked for over twenty years in technology product management, leading teams at both fast-growth, early-stage companies and larger companies attempting digital transformations. Currently, he is vice president of product at MasterClass, and before that he was vice president of product at Lynda.com, another premier online learning company. He has also worked for companies developing content and advertising platforms for independent publishers, startups creating mobile messaging and social networking solutions and has led business units based in the United States and China. Sandy is an industry fellow and lecturer at the Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology at the University of California, Berkeley, where he has developed an original set of work covering all aspects of applying product management in modern technology organizations.

—Isaac Silverman, Head of Rider Growth, Uber

“There's a lot of writing about the transactional aspects of product management: validation, user journeys, go-to-market, product economics. However, we've lacked good writing about difficult people-related product management challenges: empathy, strong cross-functional collaboration, organizational dynamics, navigating and communicating tradeoffs. This gap is now filled by Ken Sandy's The Influential Product Manager—a valuable resource for aspiring product managers as well as senior product leaders.”

—Rich Mironov, startup CEO and author of The Art of Product Management

“Product managers are the nexus of innovation and vision, communication and emotional intelligence, negotiation and prioritization, all with the goal of delivering products customers love. The Influential Product Manager is the definitive guide to understanding why these attributes are so important and how they lead to better product design and development. Most important, it goes beyond business strategy to focus on how to align various stakeholders and teams, drive effective decision-making, and how to be influential and inspiring even without formal authority.”

—Tanya Staples, Vice President of Product, Learning Content, LinkedIn

“There's a fine line between healthy influence and unhealthy manipulation. To be an effective product manager, you need to understand the difference and become a master of positive influence. In this book, Ken Sandy expertly shows you how to use this superpower for good and avoid its dark side. Read it now; your career and your team will thank you.”

—John Vars, Chief Product Officer, Mixhalo, and former Chief Product Officer, TaskRabbit

“I wish I had this book when I started my product career ages ago. It would have saved me tons of time and heartache as I learned many of these lessons the painful way. It's an easy, succinct read and covers the core foundations that every product manager should know and master. It will be mandatory reading for our incoming associate product manager class and a worthy read for all product managers looking to hone their craft.”

—Joff Redfern, Vice President of Product, Atlassian

“It's the instruction manual (and now my go-to desk reference) that only the most seasoned, thoughtful, honest product guru and mentor could create—guiding you through the hiccups of making truly great products and even demystifying tough topics like how to go about understanding users' needs and how to collaborate with your team while leading them too.”

—Marisa Gallagher, Head of UX and Design, Amazon Music

“This book outlines stellar frameworks and, more importantly, philosophical guidance on how Product and Engineering can build relationships, collaborate effectively, and share mutual respect. While the companies I've worked for have had a variety of cultures, ultimately the core principles around effective collaboration stay the same, and this book shines a bright light on these principles for both Product and Engineering leaders to embrace.”

—Eric Bogs, Engineering Leader, Facebook, and former engineering leader, Google, Spotify, Yahoo!, Etsy, and Hinge

“The Influential Product Manager captures the art of product development all in one place. Ken Sandy emphasizes courage, focus, commitment, respect, and openness, which strike me as values that apply to all aspects of product development, from ideation and design to implementation and delivery to the customer. I plan on recommending this book to all my product management, engineering, and design colleagues as an excellent guide to working together to delight our customers and build great products!”

—David Zabowski, Vice President of Engineering, Nerdwallet

“The Influential Product Manager is essential reading for both product managers looking to hone their craft and stakeholders who would like to improve their working relationship with a product organization. Ken Sandy packs his incredible talent for coaching and developing teams onto the page, providing the most comprehensive survey of the product discipline and tools for success that I've ever read.”

—Matt Sanchez, Senior Vice President of Platforms, Hearst Magazines

“Ken's book is a fantastic addition to the product manager's toolbox. It's unique in that it provides a comprehensive 360-degree view into the product manager role, and it's full of practical insights that product managers can take to work right away. This is going to be an essential part of product boot camps for my team, and I recommend that all product managers in India building for the next billion users read this book to sharpen their craft.”

—Rahul Ganjoo, Vice President and Head of Product, Zomato

“The Influential Product Manager is an in-depth playbook that's perfect for both those new to product management and those who want to have an even greater impact on product at their company. This is my new go-to resource for how to be an effective strategic partner throughout the product development life cycle.”

—David Sherwin, coauthor of Turning People into Teams and author of Creative Workshop and Success by Design

“Ken Sandy's book does an amazing job of breaking down complex concepts, helping product managers learn the discipline it takes to wade through the sea of data to find the signal in the noise. This book gives you tried and true, practical frameworks for solving problems as a product manager and ultimately for your customers.”

—Rachel Wolan, Vice President of Product, LiveRamp

“Early in your career, leadership comes not because you are the smartest but because you ask the right questions and have the tools to lead your team to the right answers. The Influential Product Manager provides a complete tool kit to help you succeed in your new role.”

—Mark Cook, Vice President of Product, Trax Retail

“This book offers critical insight on practical product management strategies, from how to influence complex organizations and how to break down complex problems to get (the right) stuff done!”

—Daniele Farnedi, cofounder and Chief Technology Officer, Solv; former Chief Technology Officer, Trulia; and former Director of Technology, Shopping.com

“This valuable guide will help product managers lead their organizations and better serve their users and will help product executives uplevel their team's effectiveness and business impact.”

—Brent Tworetzky, Senior Vice President of Product, InVision, and former Executive Vice President of Product, XO Group Inc.

“Excellent practitioner's guide for budding and experienced product managers alike. What sets this book miles apart is the way Ken draws from his experience, goes beyond theoretical advice, and provides excellent examples and pragmatic techniques to become a successful PM. This book is a must-read for every tech product manager in India.”

—Sachin Arora, cofounder of Chqbook.com and former Chief Technology Officer, Myntra.com

“Unlike so much literature in this field, Ken has not adopted a ‘one size fits all' approach but rather has drawn on deep, practical experience to craft a coherent and pragmatic guide for product managers working on any internet-based product. The net result is that by reading this book, literally all product managers will become more effective in their organization. This will be good for them, their teams, and their company. It will result in less wasted time and fewer failed projects.”

—Martin Hosking, cofounder of Redbubble

CHAPTER 1

First, Think Like a Product Manager

Differentiate yourself with four powerful mindsets.

What you’ll learn in this chapter

1 Four mindsets that influential product managers deliberately employ—with strategies you can use in your daily work throughout the product lifecycle.

2 How you can generate superior customer and business outcomes through a more motivated team focused on executing against the product vision.

3 Ways to detect and navigate common pitfalls and techniques and to avoid common cognitive biases you may face.

Four Mindsets Influential Product Managers Use

It’s a cliché but, oh, so true—ideas are cheap. Few organizations are struggling for new ideas—most have too many and struggle to figure out which are most likely to be successful. And they are often challenged to execute them smoothly while maintaining highly motivated, collaborative teams.

For example, there are significant differences between the following:

• Conceptualizing a high-level business opportunity versus investing in understanding the customer to discover problems worth solving.

• Having product ideas of your own versus gathering and embracing ideas regardless of whether they come from inside or outside an organization.

• Defining a potential solution (full of assumptions) versus validating and prioritizing which of many options are worthwhile to pursue.

• Driving a project execution plan versus motivating everyone and organizing everything needed to execute well.

• Launching a product versus ensuring customer adoption and market success.

Influential product managers understand that success in their role lies in the latter part of each statement, not the former. They employ a set of fundamental, and sometimes contradictory, mindsets. These guide their approaches to daily work and their actions throughout the product lifecycle.

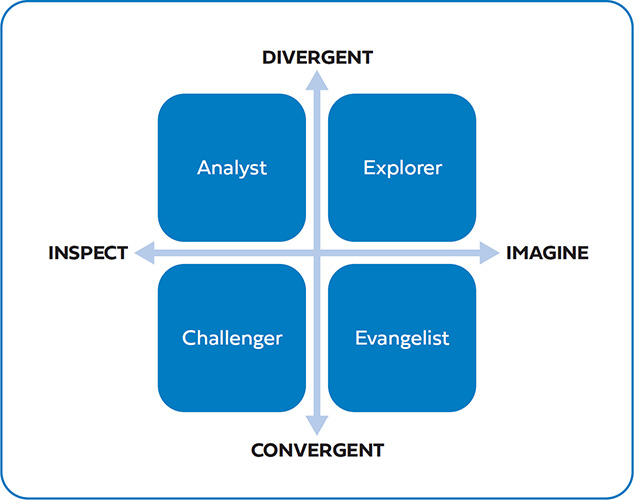

So how do you discover new possibilities and excite others with their potential? How can you prioritize and validate many potential initiatives? How do you remain balanced and objective, aware of hidden downsides and assumptions? And once you give something the green light, how do you ensure a smooth execution and keep up the momentum? Start with explicitly employing these four powerful mindsets, as highlighted by the framework in Figure 1.1.

Consider a simple matrix with two axes. On the horizontal axis on the far right is imagine. To imagine means to be open to discovering opportunities and potential solutions; to build excitement for new possibilities and to suspend long-held beliefs and ignore limitations. On the far left is inspect. To inspect is to gather data to build customer empathy and discover hidden insights, assess product performance, evaluate new opportunities, and uncover risks and issues.

On the vertical axis (at the top), engage in divergent thinking to broaden your perspective. Brainstorm, discover, and share data; explore parallel paths of inquiry and make sure not to adopt any particular approach prematurely. At the lower end, engage in convergent thinking. Focus is essential once you have decided to pursue a path, allowing you to challenge assumptions and mitigate risks, strengthen and deepen your understanding in your plan, and to build momentum. Avoid distractions, misalignment, analysis paralysis, or constant revisiting of the options you have already dismissed.

Each of the resulting four quadrants represents a specific mindset you can employ. Each is essential to influential product management. You must be ready to imagine the possibilities and brainstorm options (the explorer mindset), and yet you must know when to focus and motivate a team toward a singular goal (evangelist). You must gather data to discover hidden gems (analyst) but ask the hard questions to eliminate the less-promising paths (challenger).

You may find yourself flipping from one mindset to the next throughout the product lifecycle; you may even appear to contradict yourself. For instance, you might be evangelizing a product opportunity but at the same time challenging assumptions and finding reasons not to pursue it.

Pay close attention to your natural decision-making process and biases, and make it a practice to employ other mindsets. Look, too, at the preferred mindsets of others involved in the decision-making process, as you may need to provide balance by applying a contrary point of view.

In the rest of this chapter, I will review each mindset along with actionable recommendations, pitfalls, and common biases that undermine objectivity and can lead to poor results. You can find a checklist to remind you of specific recommendations online at http://www.influentialpm.com.

Drive Innovation with an Explorer Mindset

With the explorer mindset, you’ll understand the power of vision—and seek many, sometimes unexpected, paths to reach it. You’ll use creative thinking to identify opportunities and potential approaches to address your customers’ needs.

Don’t adopt too specific a product implementation too early. Instead, allow yourself the flexibility to work in “problem mode”—before moving to “solution mode”—to explore and experiment.

Adopt an explorer mindset by starting with these recommendations:

1. Define your target customer, problem statement, and a product vision.

2. Canvas broadly for opportunities and ideas.

3. Validate and create prototypes of potential solutions concurrently—and continue gathering feedback throughout the lifecycle.

1. Define Your Target Customer, Problem Statement, and a Product Vision

Set a “North Star.” Clearly articulate what you are trying to achieve, why, and for whom. Make sure everyone involved with your product has a shared understanding of this vision as it is the basis of everything you will do together.

Don’t be surprised to discover that you have multiple customer types to serve. For example, a marketplace must attract buyers and sellers; the economic buyer of an enterprise solution is typically not the end user. Each customer or user type has different needs you must satisfy with your solution.

Developing empathy for your customer can only come from regularly meeting with and observing them in person to fully understanding their challenges. Use simple tools—such as personas and value propositions—to capture and communicate your findings. Focus on describing the customer, their desired outcomes, and the benefits you offer—not your business goals or the product’s feature set.

A good product vision describes the underlying motivation and desired outcome for your user—not your proposed solution. Your vision must hold true regardless of which solutions you pursue. Make it exciting—a stretch, but still obtainable. You are giving your team context and permission to think big.

There are many approaches to stating your product vision. A popular one is the elevator pitch proposed by Geoffrey Moore in Crossing the Chasm. I recommend the following revised template, based on his:

[Product Name] solves [meaningful problem] for [target customer] by providing [benefits or value propositions]. We’re interesting because, unlike alternatives, [unique differentiator] .

As an example, drawn from Chapter 3 , I introduce a product called Babylon (more is described in that chapter). Using the revised template, the vision statement for the product might be the following:

Babylon solves the desire of urban professionals to live a greener, healthier lifestyle by providing cost-effective and convenient access to hyper-local, fresh, organic produce. We’re interesting because, unlike alternatives, our fully automated and space-efficient solution eliminates the time-intensive process to learn and maintain the otherwise manual, error-prone and complicated alternatives currently on the market.

Chapter 3 covers five key questions to answer in order to understand your customer and build a compelling vision—the “North Star” for your product.

Chapter 3 covers five key questions to answer in order to understand your customer and build a compelling vision—the “North Star” for your product.

2. Canvas Broadly for Opportunities and Ideas

Be open to finding ideas from both inside and outside your company (such as from team members, stakeholders, customers, competitors, and other products). Don’t just seek solutions to known problems; also look for new problems to solve.

Schedule regular brainstorming sessions with colleagues and collect their insights. Structure your brainstorming session to be effective, constraining it around a specific, focused goal. Capture ideas in a backlog and prioritize them, bringing the most promising opportunities into your product roadmap.

Visualize Your Product (before You Build It)

Many people respond better to visuals (show) over text (talk) to communicate a vision. Here are two standard approaches to using visuals for this purpose:

1. Produce a design mock-up for a possible “end-state” for your product. For example, if your product is a website, show a mock-up of the homepage with essential functionality that would be available to users once it is entirely built—even if that is many years away.

2. Create a “customer journey,” showing the before and after, helping to illustrate how the product will change the end user’s life. Show each step the customer must take to solve the problem today and contrast it with how much easier this process will be once your vision is fully realized. An example customer-journey map can be found online at http://www.influentialpm.com.

Don’t fall into the trap of attempting to design your product at this stage. You are not creating specifications to give to the user experience and engineering teams to implement: you are creating a communication tool.

And take care not to make your mock-ups too perfect looking—even a hand-drawn concept can be enough to spark rigorous conversation.

Chapter 3 outlines how to identify and evaluate your competitors—including what to look for in a teardown to learn effectively from their solutions.

Chapter 3 outlines how to identify and evaluate your competitors—including what to look for in a teardown to learn effectively from their solutions.

Chapter 4 introduces the KJ Method: an excellent approach for brainstorming ideas and aligning stakeholders around priorities.

Chapter 4 introduces the KJ Method: an excellent approach for brainstorming ideas and aligning stakeholders around priorities.

Use your own product frequently (surprisingly, many product managers do not). Complete product “teardowns” by identifying related products and experimenting with them, using them side by side with yours. Note how they function, how they are designed, where they are intuitive, or where they have elegantly solved a problem. In addition to looking at competitors’ products, explore adjacent product categories and products with similar business models but in different industries. Take screen captures and post them on a wiki for future reference and a source for new ideas.

3. Validate and Create Prototypes of Potential Solutions Concurrently—and Continue Gathering Feedback throughout the Lifecycle

Validation with prospective customers can be challenging, particularly early in the product lifecycle when the potential solution isn’t fleshed out. As a result, many product managers do it too infrequently, start too late in the process, or make it more complicated than it needs to be.

Chapter 5 covers approaches to discovery, prototyping, and validation to generate optimal outcomes for your customers and business.

Chapter 5 covers approaches to discovery, prototyping, and validation to generate optimal outcomes for your customers and business.

At the beginning of the product-development process, you want to improve your understanding of the problem and uncover possible solutions. Before committing to a single approach, create mock-up alternatives and test them with a group of actual or potential users (and internal stakeholders). For the best use of time and resources, keep to a couple of concurrent ideas and cull early in the process, when it’s apparent something isn’t working. Often, you’ll find that a hybrid solution gives the best results.

By continually testing throughout discovery, design, and implementation—even if on just a few customers each time—you are always gathering new insights and refining your solution with feedback.

Using the Explorer Mindset to Find Hidden Opportunities

I was consulting for a consumer company having difficulty increasing subscriptions for their product that served college students. The number of new paid sign-ups seemed low, given the potential market and many months spent investing in optimizing the existing product.

In an all-day workshop that included business, executive, and development team stakeholders, we started by revisiting the product vision. The current product offered only incremental, occasional homework help for students—with low engagement rates. We set our sights on making it an essential, everyday study companion instead.

We reviewed research comparing what students needed versus what we were giving them. During brainstorming, we identified five high-potential opportunities including virtual study groups, test prep, access to live tutors, and personalized content collections—none had previously been considered for the roadmap.

Finally, we looked at other subscription-based products we admired (none were competitors). We identified improvements to sign-up and registration flow we could test that might encourage more trials and personalize the experience for greater conversion.

While a one-day session wasn’t going to make the product instantly more successful, in exploring the possibilities, we unearthed new ideas that were deserving of testing. Together these ideas had the potential to substantially improve student outcomes and business results.

Such exploration doesn’t have to take weeks or be a costly venture—you are creating lightweight deliverables, not fully working solutions. Your prototyping can be as simple as paper sketches or high-level flows (enough to communicate your overall concept), clickable mock-ups (to simulate a high-fidelity, user-facing experience) or working prototypes (where a user can interact and explore as if the product is real even though, in reality, most of the engineering is not functional).

Note that the deliverable from this process is the ability to validate a hypothesis or learn something new, not the prototype itself. Resist letting stakeholders confuse working prototypes with a finished product—you must be prepared to allow engineering to rebuild for quality.

Develop Customer Understanding with an Analyst Mindset

To understand your customer and their unmet needs, use the analyst mindset. Invest in direct customer relationships to build empathy and to divine insight. Dig deep into product data to understand hidden trends, new insights, or unexpected discoveries—and share your findings liberally to create a shared understanding and to set context across the team. You must be objective and intellectually curious, open to surprises that contradict your current thinking.

You’ll gather and interpret quantitative and qualitative data from a broad variety of sources. Data is often not readily available, so you will have to gather it by doing your own research or running experiments.

Quantitative data are gathered by tracking user behavior or by surveying a large customer base, and they are then used to spot statistically relevant trends. Quantitative data alone might not provide clear, actionable insights that tell you exactly what is needed, however, so you must combine quantitative and qualitative data to understand the full picture.

Qualitative data help explain the underlying reasons for an issue or reveal unknowns, and while they are not statically relevant, they provide insights into underlying customer motivations. You must actually talk to users and potential customers one on one. The results of consumer or market research studies might help surface trends and observations, but real insights that catapult your product forward come from dialogue with real users.

Adopt an analyst mindset using these recommendations:

1. Set and monitor quantitative performance metrics for your product.

2. Develop a rich qualitative perspective by observing and interviewing customers.

3. Become your own analyst

1. Set and Monitor Quantitative Performance Metrics for Your Product

Select metrics that get to the heart of delivering long-term value to customers and your business. For example, simply tracking user acquisition or revenue—while giving you information you may want to know—does not necessarily tell you whether users are regularly engaging with and deriving value from your product, or whether you have a sustainable business model.

Determine and gain agreement among stakeholders for your key performance indicators (KPIs). If possible, benchmark against products with similar business models to set reasonable targets. Do this to make sure everyone has realistic expectations.

In Chapter 11, I provide recommendations on KPIs for customer satisfaction and your product’s long-term financial success, and I reveal what distinguishes good metrics from poor ones.

In Chapter 11, I provide recommendations on KPIs for customer satisfaction and your product’s long-term financial success, and I reveal what distinguishes good metrics from poor ones.

Recognize, especially in enterprise settings—where many different groups may have opposing goals, incentives, and metrics—that getting consensus may not be easy. For example, a sales team might emphasize goals to help them close deals, taking resources away from advancing end-user satisfaction or making it harder to find and use primary features.

Don’t just monitor high-level KPIs or make do with the standard “out-of-the-box” reports delivered by many analysis tools. Explore and understand the underlying subdrivers. By breaking out your metrics into subcomponents, you will discover which levers provide you with the greatest opportunity for improvement, focusing your product development efforts where you will have the most impact to advance your KPIs.

When creating product specifications, be sure to define tracking and reporting requirements and allow time for tracking setup and testing in your project plan—a step that is often overlooked. Without it, you will not be able to measure the impact your product has had on your customers and business.

2. Develop a Rich, Qualitative Perspective by Observing and Interviewing Customers

Get out of the building regularly—several times a month at least—to build empathy and gather breakthrough insights. Join sales calls. Get involved with any user-experience or customer-research activities your company is undertaking, particularly in-person interviews. Don’t just test your existing product or ideas; try to learn more about the customer, their environment, and why they use your product.

Chapter 5 includes interviewing techniques you can use to gather insights from your customers and inform your product direction regularly.

Chapter 5 includes interviewing techniques you can use to gather insights from your customers and inform your product direction regularly.

It is essential to set up your own interviews with your own objectives and not just listen in on others’ sessions. Negotiate access to perform this primary data-gathering and show you can be trusted with clients (especially if you want to earn trust from sales teams in an enterprise or in B2B companies).

Read customer-service emails or reviews about your product—scan them for common themes, particularly repeating issues, concerns, or unmet needs. Find external or internal market reports to read. Write down questions as they come to you, as these can help you identify analyses you should be doing or form future hypotheses to test. Do not take results at face value—get to the “why.”

Analyze Data to Look for Unexpected Trends

At a digital media company I worked at, we noted that our ads, when shown on mobile devices, had much lower click-through rates than when displayed on desktop computers.

It was 2011, and we were convinced that the disparity mainly came from smaller screen size and longer load times. Add to that the fact that mobile ads were simplified versions of their desktop counterparts, and were less relevant (as, at the time, mobile targeting technologies were still in their infancy). And, because mobile phones are more social, intimate devices, we suspected that mobile advertising just wasn’t something people were comfortable with yet.

Interested in exploring these hypotheses, I looked at user performance for specific devices and operating systems to see if there were any patterns (such as lower engagement rates on smaller, less advanced phones or demographic differences between their user bases). With both platforms still relatively new, iPhones were performing much better than their Android counterparts overall—but that did not seem to fully explain the gap. The breakthrough came when we noticed several popular Android phones were getting a high number of ad impressions but no clicks at all.

We had mistakenly assumed demographic and form-factor differences explained the gap—but a bug in our ad-serving technology affecting some Android phones was the greatest culprit. Now we knew how we could improve our results, and it was with something well within our control.

3. Become Your Own Analyst

While some organizations have a team to provide analyses and reports, you should not rely entirely on others for your needs. Why? Consider the following:

• Unless you cut and slice the underlying data yourself, you can miss anomalies or surprise realizations, or fail to see data that has been misinterpreted. You’re unlikely to get the full story from canned reports and secondhand information.

• Your ability to learn and iterate quickly may be slowed if you need others to provide you with all your analysis. Whether you’re relying on your marketing, sales, or business-analytics team, all of them typically have many other internal customers they also need to service.

• If you can self-service your reporting needs, you can reframe and tweak your questions without delays. Asking the right question up front is hard; more than likely you’ll have to go back to re-analyze or augment your data, requiring additional requests.

Practice the skills that allow you to gather raw data from trusted sources. As needed, in addition to partnering with your data analytics team, perform your own quick-and-dirty analyses, so you can learn and iterate quickly. Do not be afraid to learn new tools and techniques—especially SQL and advanced Excel functions. Answering a question that’s been on your mind can be a fun downtime or late-week activity.

Chapter 11 details five categories of metrics that product managers analyse to uncover insights—surfacing the areas of greatest opportunity within their products.

Chapter 11 details five categories of metrics that product managers analyse to uncover insights—surfacing the areas of greatest opportunity within their products.

Segment and cohort data to find insights otherwise hidden in the “averages.” Averages are a trap. Insights come from understanding unusual distributions or trends over time, or observing unexpected behavior within a particular user segment.

Conversely, many products are data-poor or badly instrumented. Misinterpretations can quickly arise if you’re not careful. Your entire week can quickly become occupied with wrangling a difficult data set. Push for clarity and understanding of data definitions, escalate to your manager any need to support the purchase of better tools or training, and understand that even with data in hand, not all decisions are easy—especially as people interpret data with different lenses.

Techniques to Equip Yourself for Self-Service Analytics

Depending on your organization’s policies and level of maturity in data analytics, consider the following options:

• Become an expert in using your company’s reporting tools.

• Learn advanced Excel—especially pivot tables, charts, look-up functions, filtering/sorting, and VBA.

• Learn SQL so you can manipulate data yourself. Product managers often have to fight for attention from data teams, so empower yourself to DIY.

• Negotiate read-only access to non-production databases or ask for a daily (or weekly) data dump for select data.

• Subscribe to one or two key market-research companies serving your industry.

• Negotiate direct access to customers and users for interviews to gather supporting qualitative insights.

• Petition for dedicated analysts to be assigned to support the product team.

• Make a close friend in data analytics.

Identify and Mitigate Risks with a Challenger Mindset

The challenger mindset shines a light on contrary data, flaws, and hidden assumptions, helping you to preempt potentially serious issues. Your goal is to seek out what can go wrong, even when everything looks overwhelmingly positive.

Look for gaps in your understanding and guard against cognitive biases. Approach each step as simply a hypothesis that requires validation or disproving. Remain objective by critically validating your assumptions. You’ll poke holes in some bad assumptions, but you’ll also strengthen good ideas. You may identify risks that can be easily mitigated or raise the alarm when the risks require more thoughtful decision-making.

Maintain healthy skepticism. Be open to the possibility of being wrong and accept criticism without becoming defensive; instead, be unafraid to embrace constructive conflict as it battle-hardens your product. And, when warranted, recommend a change in course.

Finally, be ruthless in prioritization decisions, so that you and your teams can focus on the highest-value activities.

Adopt a challenger mindset using these recommendations:

1. Approach all opportunities as hypotheses requiring validation.

2. Embrace dissenting voices and constructive conflict.

3. Focus, prioritize, cut.

1. Approach All Opportunities as Hypotheses Requiring Validation

Do not assume your product plans, no matter how compelling, are sure to be worthwhile. This holds true whether you are prioritizing small feature enhancements or embarking on entirely new product initiatives. And it’s true even, and perhaps especially, when the idea comes from someone highly respected and more senior than you.

Start with a hypothesis. A simple framework for creating one is as follows:

We know that [data or observation] and believe that [need or issue]. Through delivering/testing [concept] for [target user] , we expect [measurable outcome] .

The framework forces you to articulate what facts you know, what you suspect is the underlying cause, what your product idea or concept is, and what metric you expect to move. It is a powerful context-setting device for your team that also leaves you space to collaborate on and craft the solution. It drives focus and accountability, and it establishes a platform in which you will likely learn something new (even if the idea fails).

It is even more powerful to propose a null hypothesis. For example, when testing whether something lifts sales for retailers, the null is that the action does not make a difference. Your new feature drives no new sales. By trying to prove the null hypothesis true, you can be at your most objective.

The Psychology behind a Hypothesis-Driven Approach

Switch to hypothesis and test mode, and you can help offset any personal attachment you have to an initiative. Rather than staking your reputation on being right or feeling it’s not in your best interests to dissent with the consensus direction, your approach should be seen as that of making judicious use of scarce resources to guide the business to success.

Oh, and being “wrong” is okay—if you learn something new. It is powerful when a product manager says that they are wrong in front of a team. It demonstrates that you are unconcerned by ego and are objective in your search for the right answers.

Chapter 6 covers how to start with a hypothesis and define your product specification to build the minimum product scope necessary, speeding your time-to-market and your learning as quickly as possible.

Chapter 6 covers how to start with a hypothesis and define your product specification to build the minimum product scope necessary, speeding your time-to-market and your learning as quickly as possible.

In Chapter 4, I introduce how to approach split-testing and incremental product optimization.

In Chapter 4, I introduce how to approach split-testing and incremental product optimization.

For incremental optimizations requiring little effort, you can build and deploy a split test—an experiment that definitely determines whether the idea causes better outcomes. For larger product efforts, continuously gather qualitative and quantitative data during definition and implementation to increase confidence and adjust direction in response. Post-launch, be sure to measure outcomes and seek optimizations if you have not hit your goals.

2. Embrace Dissenting Voices and Constructive Conflict

New opportunities can seem exciting, and their potential promising. When they’re enthusiastically endorsed by a majority (“groupthink”), those who disagree or are less convinced will often stay silent (or be silenced). Pretty soon, all the data presented seem to support pursuing the current path (“confirmation bias”).

Seek out and embrace dissenters—peers, stakeholders, or customers that appear unsupportive or even negative. Do so one on one, rather than in large groups, so that later you can help frame and present concerns to a broader set of stakeholders without discrediting the dissenter.

Avoid defensiveness or dismissing concerns out of hand. Respect the value of diverse personalities, skills, and experience. Try to understand their objections and integrate these into your evaluation. Seek to prove them right, not wrong. And don’t take to heart everything they say—they usually aren’t attacking you personally.

Chapter 2 covers powerful techniques for engaging stakeholders, including surfacing potential areas of misalignment.

Chapter 2 covers powerful techniques for engaging stakeholders, including surfacing potential areas of misalignment.

In Chapter 3 you will find advice on identifying risks and assumptions—before you start building solutions.

In Chapter 3 you will find advice on identifying risks and assumptions—before you start building solutions.

Don’t be afraid to challenge others diplomatically or to communicate bad news thoughtfully. If you don’t confront issues that may undermine the success of the product and, at large, the business, you’re not doing your job. But remember to critique content, not people—constructive conflict comes from a position of trust and assumes all parties are approaching the issue with good intent.

Share all data and insights you have, so that others can confirm or challenge your conclusions. During product updates and in decision-making forums, don’t just present your initiative in a positive light so that it will be approved. True, your role is to garner support, but include assumptions, scenarios, and risks that might paint a less rosy picture so that sound decisions can be made.

Challenging Assumptions and Communicating Bad News

One of our company goals was to ready our platform to support the globalization of the business with all that entailed—multiple languages, currencies, marketing platforms, pricing, and packages. I was among a team of product managers and engineers asked to assess all the activities and time required to complete this mammoth task—nothing short of the rewrite of a platform that had been built to serve only a single (U.S.) market. To their credit, the team did not shy away from presenting the bad news: it would take three years.

Not surprisingly, this didn’t fly. We set about challenging our assumptions, in the hope we could reduce the scope or find creative approaches. We asked questions such as these:

• Is there a smaller set of customers (still accounting for a sizable portion of the opportunity) we can build for first?

• Do we need to offer a full-featured solution, or will local markets be okay with a simplified offering?

• Can we partner with third parties in some markets, until we’re ready to launch our own solution?

We realized that 80 percent of the market opportunity came from serving a sub-segment of enterprises that required a much smaller core offering. This would reduce the work by half (such as local marketing, pricing, or currency support). By partnering (licensing a partner platform but with our brand and content), we could support consumers in three other markets.

The original plan assumed everything was required out of the gate, without considering whether this was necessary. While the new plan was ultimately agreed upon, we would have saved time had we asked all the pertinent questions earlier.

And if you happen to win them over in making the idea a success, then all the better!

3. Focus, Prioritize, Cut

There’s no shortage of problems to solve and ideas to pursue. So as much as you decide what to do, also determine what not to do. Prioritize the ideas with the most potential and explicitly deprioritize the rest.

You will add more value by avoiding distractions and ensuring a thorough evaluation of each initiative in the development pipeline. Get this right, and you will avoid not only significant direct costs but also opportunity costs (which are often hidden and more insidious). Imagine, for example, that you have one high-potential idea and another that’s not; both require the same investment, such as development resources (“direct costs”). Pursuing the wrong idea sets you back not only the direct cost but also the opportunity cost of delayed revenues or forgone growth in not pursuing the high-potential idea earlier.

Your process to decide which ideas to prioritize should be well defined and robust, but it need not be time-consuming or involve too detailed a cost-benefit analysis or business case. Many initiatives have too many unknowns to quantify the outcomes accurately at the outset.

Instead, it is equally valid to use methods that endeavor to establish shared outcome-oriented goals and then (using the best data you have) collaboratively score or rank initiatives to fulfill the goals. Such methods inherently drive stakeholder alignment—permitting focus on the items likely to have the highest impact, empowering product managers to drive toward outcomes rather than specific projects, and reducing context-switching between many competing alternatives.

In Chapter 4, I present techniques for collaborative prioritization among a stakeholder group—focusing first on aligning objectives and then on determining the initiatives likely to advance these goals.

In Chapter 4, I present techniques for collaborative prioritization among a stakeholder group—focusing first on aligning objectives and then on determining the initiatives likely to advance these goals.

In Chapter 9, I outline one of the trickiest challenges facing product managers—navigating and communicating scope-time-quality trade-offs.

In Chapter 9, I outline one of the trickiest challenges facing product managers—navigating and communicating scope-time-quality trade-offs.

Take care not to waste time revisiting and discussing the same ideas repeatedly or exploring left-field ideas that have little to do with your business priorities or customer needs. You can add them to an ideas backlog for possible consideration in the future.

Challenging Others: How to Say “No” Nicely

Particularly with senior colleagues, but also with peers, you want them to see you as supportive, aligned, and undemanding. Try not to challenge others too directly unless you have built a healthy relationship where this is appropriate, but neither shy away from confrontation when you believe an alternative path is the right thing for the customer and business. Importantly, do not fall into the trap where you are merely responding to stakeholder demands (also called an order-taker, where the product organization is simply a service organization doing the bidding of other departments).

When you must challenge others, start by reiterating the useful insights they bring. Then try using the following questions and approaches:

• “Given that our objective for this quarter is X, how does your idea help us with X?”

• “What data might we gather to confirm which path to take?”

• “Who else would need to be involved in deciding a trade-off?”

• “Thanks for the idea—compared to existing priorities A and B, help me with why we should prioritize this higher?”

• “Walk me through your thinking about....”

• “Have you considered Y alternative?”

• “Here’s the data I see. What am I missing?”

• “I’ll put the idea in the idea backlog.” This shows that you won’t forget about it—but avoids setting expectations as to when you will address it.

• Rather than debate, recruit them to help you address current priorities. Ask them to own an important task.

Even agreeing to evaluate an idea is still committing resources away from core priorities. Be aware of pursuing too many parallel lines of inquiry with limited resources. Sometimes you just have to be firm and say no.

As a project gets underway, be prepared to make tradeoffs early and quickly—starting at the scoping and specification stage. Nobody likes to compromise, especially once you have put work into defining an elegant product solution you think is sure to solve all your customers’ needs. Unfortunately, sticking with your best intentions can slow your time-to-market (and postpone your learning from real customers). Or you may unintentionally make engineering take shortcuts so they can meet a deadline, which, over time, accumulate to undermine the quality of your product (known as “technical debt”).

Scrutinize every feature during the definition stage and manage scope creep aggressively. You need to ensure that everything is essential to delivering customer value and that no features are incrementally so demanding that they mean you can no longer ship quickly. The sooner you ship, the sooner you can start learning from customer feedback and know what’s required in the next iteration of your product.

Likewise, be very cautious about making timeline commitments before you and your engineering team have time to discover and assess the work ahead of you. Nothing diminishes respect for a product manager faster than committing an engineering team to an unreasonable deadline with a scant, unvalidated product scope.

Build Momentum with an Evangelist Mindset

With the evangelist mindset, you can motivate your team and build company-wide support. Your goal is to get them to focus with enthusiasm on the initiative’s potential. You want to turn stakeholders into believers. You want the team to unleash its creativity on the problem at hand—so that the solution generated is even better than you thought possible.

Develop trusted internal relationships early, then leverage these to excite and align stakeholders behind your plans—while enabling their teams to take ownership and guide the solution’s direction. Understand there is greater power in articulating the “why” over the “what” or “how.”

Adopt an evangelist mindset by starting with these recommendations:

1. Communicate plans to your stakeholders proactively and keep them updated regularly.

2. Set context rather than prescribing solutions—and lose ownership to your team.

3. Carefully manage planning, collaboration, and communication before, throughout, and immediately after product launch.

1. Communicate Plans to Your Stakeholders Proactively and Keep Them Updated Regularly

Identify internal stakeholders and share with them your plans and data; then gather their input and incorporate it. You want to build goodwill toward you and your product, reminding everyone of the beneficial impact for customers and the business. Share your assumptions and your understanding of the risks, possible tradeoffs against other initiatives, and investment needs. Share how your current product, if in the market, is performing, while stressing that continued investment is beneficial to the company.

In Chapter 2 I discuss how to identify and maintain strong relationships with stakeholders effectively—setting context and keeping them up to date and supportive.

In Chapter 2 I discuss how to identify and maintain strong relationships with stakeholders effectively—setting context and keeping them up to date and supportive.

Even after you receive approval or support from decision-makers, don’t stop the roadshow. Find opportunities to reinforce why your plan is a priority, especially to those who will be implementing a product initiative, selling it, or otherwise supporting it.

2. Set Context Rather Than Prescribing Solutions—and Lose Ownership to Your Team

Team members are usually most motivated by their impact on customers and the business (the “why”). They are much less enthusiastic about being prescribed a specific solution (the “what”) and are especially sensitive to being told “how” to go about building the solution or “when” it has to be completed. So get them excited about potential customer and business outcomes. Provide them with support and air cover from distractions. Show respect for the problem-solving abilities of your team and emphasize the goal over your own solution.

Finding Evangelism Opportunities

• Develop your 30-second elevator pitch and a ready-to-go set of slides outlining the customer problem, the business opportunity, and your vision and solution. Walk through the information with stakeholders.

• You may be asked to provide product updates at important meetings or the company all-hands gathering. No matter how nerve-racking, embrace these opportunities—or even volunteer.

• Hold a “brown-bag meeting” at lunchtime for interested parties to attend. Topics can include your product roadmap, things you’ve learned about the customer, interesting trends, or outcomes of new feature launches. Keep it to about 30 to 45 minutes and include time for Q&A.

• Send a weekly email to team members that includes notable achievements, learnings, customer quotes, and callouts. Keep your emails lively and not just full of status updates. A template is available online at http://www.influentialpm.com.

Allow others to take control and make the product theirs. This can be hard if it has become your “baby.” But you need a cross-functional team with diverse skills to make it a reality. Let them set the approach and break down the plan. Articulate a need from the customer’s perspective and leave plenty of room for others to influence the target solution. Whatever they come up with will usually be better than, or at least as good as, what you imagined.

Chapter 7 outlines how to take a user-centric, goal-driven approach to requirements. User stories leave extensive opportunity for your team to shape the product solution.

Chapter 7 outlines how to take a user-centric, goal-driven approach to requirements. User stories leave extensive opportunity for your team to shape the product solution.

Chapter 8 details how to effectively engage engineering and guide your product through the development process—keeping your team focused and energized, and continually delivering value.

Chapter 8 details how to effectively engage engineering and guide your product through the development process—keeping your team focused and energized, and continually delivering value.

You’ve probably had much more time to understand your customer’s problems, evaluate options, and develop potential solutions than others around you have. It is natural for you to be further out in front—and frustrated when your team don’t seem to “get it” quite like you do.

Recognize this and patiently take them through your thought process and data, and then let them arrive at similar outcomes or possibly a different interpretation of the same data. Having conducted a thorough analysis, you’ll be ready to preempt and answer many questions—building their confidence in your product plan and in you. You’ll often find this is enough to get their buy-in.

Losing Ownership

The idea was to revamp and thoroughly redesign the website. As the site had evolved, many features had been tacked on over time without much thought about the user interface—reducing discoverability and overall usability. The problem was just going to get worse as more interactive features were added.

As the product manager, I led the redesign, outlining the vision and roadmap, and partnering with the user experience team to explore different approaches. This was a major refresh, and there were many concerned stakeholders. I conducted a roadshow to excite colleagues and address as many concerns as I could.

Simultaneously evangelizing and executing the project soon became an overwhelming task. As I was spending so much of my time addressing stakeholder needs, my development team was spinning wheels, uncertain what to prioritize next.

I realized I would be of most benefit discussing the best ideas and stakeholder feedback with the team and then letting the team independently define and own the new design and functionality.

Empowered to enact the best decisions they could, they developed a better product than they would have had they relied on me to lead everything.

3. Carefully Manage Planning, Collaboration, and Communication before, throughout, and Immediately after Product Launch

As your product initiative takes shape, it is essential that you prepare your organization for its eventual launch. As the product takes shape and its launch date draws near, your product’s stakeholder visibility increases. Invariably, people beyond your immediate team—those across many functions—need to be involved, consulted, or informed.

In Chapter 10, I discuss “deploying gently” to guide your organization through the process of bringing your product successfully to market.

In Chapter 10, I discuss “deploying gently” to guide your organization through the process of bringing your product successfully to market.

Start early, so you don’t take other departments by surprise or surface new needs late in the game. Instead, build excitement and anticipation. Ask for their contribution to the go-to-market plan. You will likely find many internal needs, such as documentation, process-setting, and approach for roll-out, need to be discussed, agreed upon, and put into place.

Finally, take responsibility for your product’s market success—not just its technical delivery. Launch is the start, not the end. Once your product is out in the world—as it is used at scale—you will see bugs surface, receive a high volume of customer feedback, and gather your first performance data against your KPIs. Stay on top of all this, communicate proactively, and seek to optimize the product to ensure long-term success.

Top Five Pitfalls to Avoid

Deploy the four mindsets explicitly and in a disciplined way, and you will avoid the most common pitfalls product managers run into when identifying, exploring, validating, and executing product opportunities. Look out for the following pitfalls and learn how to recognize and address them.

Pitfall 1—Playing Only to Your Strengths

You are likely stronger at one mindset (or a few of them) than others. Perhaps you are deeply analytical—a wizard at working with data and spreadsheets, and deriving insights—but weaker creatively. Or maybe you’re one of those people who can easily find and tackle problems, but getting on stage to evangelize your ideas terrifies you. This is normal—product managers are human, after all. Don’t think that to be successful you need to be good at everything. Be conscious of what you naturally do well and deliberately move out of your comfort zone to practice other skills. Consider asking a friendly colleague who is strong in a skill you want to gain to coach you or give you pointers.

You also need to compensate for the natural “go-to” strengths of others. Look at your team and stakeholders: What are their strengths and what are yours? Here are three examples of what that might look like:

• A visionary and thrilling founder or leader—It might be easy for you to get swept up in their vision and skip detailed critique or customer validation; however, they may be overly optimistic and scarce on details. You may need to use the analyst and challenger mindsets more often as a counterbalance, to ground their enthusiasm and help the visionary add rigor by providing data that may support or refute a path.

• A strong, decisive, and respected peer or stakeholder—Rarely wrong and demanding of action, they may be prescriptive on solution and light on rationale. Nonetheless, be aware that overconfidence or a lack of context might be taking them down the wrong path. You may need to use the explorer and challenger mindsets more often as a counterbalance, to determine alternative solutions and to ensure the problem is of high priority. Be disciplined in gathering data and developing your own point of view. Likewise, be aware they might have context or insights you don’t that you should seek from them.

• A profoundly technical or data-driven manager—While they have a good handle on the problem and solution, they tend to be highly detail-oriented and analytic. Perhaps the excitement and big-picture view are lacking. You may need to use the explorer and evangelist mindsets to help them set a vision, generate momentum, and motivate the team.

Pitfall 2—Applying the Mindsets, but Not Objectively

Your role is to guide the organization to a logical outcome, though there may still be risk and unknowns. So try to avoid the many cognitive biases that flaw much of human decision-making.

There are many cognitive, beliefs-based, behavioral, and social effects that undermine objective decision-making. Just by being aware of the most common that undermine product management decision making, you will be more likely to detect them (whether in yourself or others) and counteract them.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

The tendency to look for data that confirm a held belief, preferred outcome, or expectation. This bias is manifest through

• locking onto data that support what you want to hear;

• dismissing data that seem to disagree with your hypothesis (calling such data “outliers,” for example); or

• interpreting data in a way that generates optimistic insights to confirm your preconceptions

Counter-strategy Actively seek to disprove your hypothesis (such as by testing the null hypothesis). Embrace data that contradict your assumptions or seem misaligned with your beliefs.

AUTHORITY BIAS

A manager, key customer, or other person—in a position of power or expertise (perceived or real)—may assert information to be true or a course of action to be the preferred or correct path. The tendency is to skip a critical assessment of their directive, perhaps out of deference to their authority, fear, over-eagerness to please them, or an assumption that they must “have all the facts.”

Counter-strategy Diplomatically negotiate for time to complete discovery: through analysis, testing, talking to customers, and exploring solutions. Explain the need for you and the team to have firsthand experience of the customer problem you are solving to develop a solution that makes the best use of scarce resources.

SURVIVOR BIAS

A common flaw bedeviling customer research, user behavioral analytics, and user testing is to concentrate your efforts on those most active with your product. These users are generally more positive about your product. Active users are more visible, more easily reached, and typically more responsive, and therefore are overrepresented in collected data.

Counter-strategy Balance your research efforts by explicitly seeking out users who have stopped using your product or customers who purchased a competitive product instead of yours.

REPUTATION RISK

Once you propose and communicate support for an approach, you become personally invested. It is very easy to fall in love with your own ideas (this is called the “halo effect”). Or you may see the failure of something you have supported as a reflection of your personal failings. You become defensive and inflexible, and you reject data that contradict your belief.

Counter-strategy Be mature enough to divorce your personal feelings and professional reputation when deciding whether an approach is working or not. Embrace potential failure as a learning experience