Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

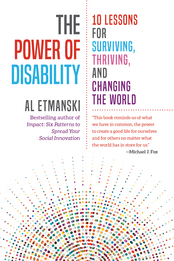

The Power of Disability

10 Lessons for Surviving, Thriving, and Changing the World

Al Etmanski (Author) | Steve Carlson (Narrated by)

Publication date: 02/04/2020

This book reveals that people with disabilities are the invisible force that has shaped history. They have been instrumental in the growth of freedom and birth of democracy. They have produced heavenly music and exquisite works of art. They have unveiled the scientific secrets of the universe. They are among our most popular comedians, poets, and storytellers. And at 1.2 billion, they are also the largest minority group in the world.

Al Etmanski offers ten lessons we can all learn from people with disabilities, illustrated with short, funny, inspiring, and thought-provoking stories of one hundred individuals from twenty countries. Some are familiar, like Michael J. Fox, Greta Thunberg, Stephen Hawking, Helen Keller, Stevie Wonder, and Temple Grandin. Others deserve to be, like Evelyn Glennie, a virtuoso percussionist who is deaf—her mission is to teach the world to listen to improve communication and social cohesion. Or Aaron Philip, who has revolutionized the runway as the first disabled, trans woman of color to become a professional model. The time has come to recognize people with disabilities for who they really are: authoritative sources on creativity, love, sexuality, resistance, dealing with adversity, and living a good life.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

This book reveals that people with disabilities are the invisible force that has shaped history. They have been instrumental in the growth of freedom and birth of democracy. They have produced heavenly music and exquisite works of art. They have unveiled the scientific secrets of the universe. They are among our most popular comedians, poets, and storytellers. And at 1.2 billion, they are also the largest minority group in the world.

Al Etmanski offers ten lessons we can all learn from people with disabilities, illustrated with short, funny, inspiring, and thought-provoking stories of one hundred individuals from twenty countries. Some are familiar, like Michael J. Fox, Greta Thunberg, Stephen Hawking, Helen Keller, Stevie Wonder, and Temple Grandin. Others deserve to be, like Evelyn Glennie, a virtuoso percussionist who is deaf—her mission is to teach the world to listen to improve communication and social cohesion. Or Aaron Philip, who has revolutionized the runway as the first disabled, trans woman of color to become a professional model. The time has come to recognize people with disabilities for who they really are: authoritative sources on creativity, love, sexuality, resistance, dealing with adversity, and living a good life.

The time has come to recognize people with disabilities for who they really are: authoritative sources on creativity, resilience, love, resistance, dealing with adversity, and living a good life.

This book does that. In sharing the stories of an incredibly diverse set of individuals, he shows how independence is only possible through our interdependence, how unity comes from embracing our differences, how opportunity is extended through a nurturing environment and expanded justice. He also tells stories of how opportunity, inventiveness, ingenuity, and clarity can arise out of adversity—while never glossing over the struggles that people face or the need to address them more collectively and more fully as a society. Perhaps it won't surprise you that two of our most transformational presidents, individuals who led the nation through some of its most challenging chapters, were individuals with a disability—Lincoln with clinical depression and FDR with polio. The ‘advantages that people with disability offer,' Etmanski writes, ‘are the perfect remedy for the troubled times we live in,' and after what I've read so far, I couldn't agree more.”

—Dylan Schleicher, Porchlight Book Company

“Hopefully the universal lessons in this book will not only empower all of us to trampoline to our highest potential but also move the global disability rights movement to achieve the success it fully deserves—so we can all live in a more just and equitable world.”

—Susan Sygall, disability activist and MacArthur Fellow

“Etmanski engages every reader, whether new to the world of disability or an old hand, with thoughtful insights on the value of difference. This book made me laugh, made me cry, made me proud.”

—Yazmine Laroche, former Chair, Muscular Dystrophy Canada

“Etmanski mines rich wisdom from the disability world and makes it accessible to a general audience. In a world increasingly divided and polarized, this book will unite, while changing the perception of disability from illness needing only charity to a normal human condition needing only opportunity.”

—Carol Glazer, President, National Organization on Disability

“In a world defined by accelerating change and interconnection, those who recognize their differences and give themselves permission to make a difference have a powerful advantage. The stories in this book illustrate how people with disabilities are seizing their power. They will help all of us see and seize ours.”

—Bill Drayton, CEO, Ashoka

LESSON 1

If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Fix It

Perfection simply doesn’t exist. Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.

—DR. STEPHEN HAWKING

The culture is constantly telling me, “This kind of body is right and your kind of body is not.” So even though I know myself as a whole person, I still daily experience the sense that this is not the right way to be.

—JUDITH SNOW

Parents get so worried about the deficits that they don’t build up the strengths.

—TEMPLE GRANDIN

What Gord Walker Taught Me

What Gord Walker Taught Me

WE ARE ALREADY as close to perfect as heaven will allow and don’t need fixes and cures to make us whole.

The first time I met Gord Walker, he took one look at me and walked out of the room. He had been a client of the disability service system for years, and he could smell a social worker like me from a distance. Gord didn’t need any more reminders that social service workers thought he was worthless. I once saw a thick file listing all the programs and interventions he had received since he was a youngster. It included behavior management programs, time-out protocols, one-to-one workers, communication strategies, psychological counseling, and medication. Apparently these weren’t working very well, because the file was also full of recommendations to fund more programs and more specialists.

Fortunately Gord gave me and PLAN, the organization I had cofounded, a second chance—a chance to develop a network of friends with him. We recruited a young woman who ignored the diagnoses and assessments that were in Gord’s files. She described them as self-fulfilling prophecies. She believed that everyone had a gift, and her job was to help people discover it. She was infused with the spirit of abundance. She was also patient. She sat in silence with Gord for many hours. She didn’t offer suggestions. She expected that his dreams would eventually surface.

One day, she came to our office ecstatic. “I’ve got it,” she said. “It’s horses.” It turned out that Gord loved everything about horses—grooming them, exercising them, cleaning their stalls, and riding them. He even wanted to own one. More than anything, he dreamed of being a cowboy, herding cattle. His passion eventually led to a job at the local stables, where he became affectionately known as the horse whisperer. He attracted a stable of friends too, connected by their shared interest in all things horsey. One of his friends was able to arrange an annual summer job for Gord riding the range as part of the largest cattle drive in southern British Columbia.1 It was the highlight of his year. He talked about it all the time. “You should come,” he would say to me. “There’s a campfire party every night.”

We live in an age that promises a cure for just about everything. Advertisers sell us products that they claim will make us thinner, faster, and more beautiful. Motivational speakers and personal coaches promise that they can make us or our children smarter, better, richer, and happier. Researchers and better-living advocates promote perfect health: just eat these foods, choose this procedure, take this pill, and practice mindfulness. We are offered a life that would have been unimaginable decades ago. Some technologists, philosophers, and genetic engineers even tantalize us with the possibility that soon all diseases will be eradicated and we can live forever.

The pursuit of perfection has its downsides. We know deep down that a lot of the claims can’t be true because, like Gord, we’ve been disappointed before. Still, the choices keep coming, and they are bewildering. It’s not easy to sort out the valuable from the worthless. To top it off, we may start believing that there is indeed something wrong with us and that perhaps we need fixing. Some of us have a deeper unease. The great religions of the world warn us against thinking we can become godlike. Popular culture is full of stories about the downside of selling one’s soul to the devil for worldly benefits. It’s called a Faustian bargain.

In reality, all of us are a mixture of frailties, inadequacies, mistakes, imperfections, and flaws—as well as a mixture of talents, strengths, and abilities. Accepting that we are all of the above is what makes us whole. The people profiled in this lesson pursue wholeness, not perfection. One believes that imperfection holds the key to the universe. Others understand that healing is different from curing. They have learned to distinguish between “fixing” that is helpful and “fixing” that is hurtful.

My wish is that we wriggle free of the grasp of the needs makers (i.e., advertisers and social service workers who create needs that they then claim they can fix) and recognize that perfection is an illusion that needs to be broken. Most of the time we don’t need to be fixed. We need to be listened to and valued.

Body Politics CATHERINE FRAZEE

Body Politics CATHERINE FRAZEE

What needs fixing are the limitations imposed by society on our ability to belong, love, and contribute.

As a child, Catherine Frazee, poet, activist, and former chief commissioner of the Ontario, Canada, Human Rights Commission, had only one wish: “to be able to walk.” Four decades later, in her essay “Body Politics,” she asked herself whether she would still make the same wish.2 The following are excerpts from her essay, written in 2000. It begins with Frazee’s two descriptions of her disability:

In the not so flattering language of medical textbooks, I am a flaccid paralytic, suffering from a genetic mutation that causes profound and progressive wasting of the skeletal muscles. My body has the consistency of overcooked pasta. . . . My body does not speak in sentences laid end-to-end and stacked in sturdy paragraphs. My not-so-normal body speaks in poetry, not prose—in sparing words, in careful disarray.

She acknowledges that many people with disabilities like hers wish to walk. She mentions that Superman star Christopher Reeves “made it his life’s work to walk again.” For others, including herself, the seductions of medical science raise personal, political, and ethical questions.

The simple arithmetic of it is that my disability has brought me smartly to all the things I value—my career, my skills, my tenacity, my intimate partner, my world view. And there is no logical reason to believe that this will not continue to be the case for as long as I remain alive.

This is not a matter of simple acceptance, of stoicism, of bravely making the best of my sorry lot. It is a matter of growing into and embracing my experience of disability. That is not to say that I embrace the exclusion, the stigma, the devalued status, the abuse, and the barriers that are the constant companions of disability. . . . These do not build character. They are as destructive and senseless as war is. I feel as impassioned about resisting these forces as others must feel about their battles to “find a cure.” But let me be very clear: stigma, barriers, and exclusion are the enemy—not my disability.

A Masai warrior she encountered while on safari in Kenya helped her understand walking as a way of belonging, of being present and proud.

From this Masai warrior, who spoke to me not in words but in footsteps, I began to understand the true nature of walking. To walk as a Masai warrior is to belong—flesh, bone, and soul. It is to declare one’s title. It is integral and devout. To walk as a Masai warrior is to assume one’s place in the cosmos—no more, and no less.

This, I can aspire to. Perhaps this is what we all wish for, in which case the contributions of medicine and technology will be at best peripheral and at worst impediments. For the purpose of locomotion, I am content to use the fingers of my right hand, the drive-stick of my wheelchair, the wheel, and the electromagnetic miracles that link the latter two so very cleverly together. For the purposes of expression, however, I want to walk as the Masai warrior. Just exactly as I do, when I am present and erect, confident of who I am and where I am going. When I know that I have every right to be here.

Brilliant Imperfection ELI CLARE

Brilliant Imperfection ELI CLARE

Bodily differences are neither good nor bad. We are all perfectly imperfect.

Poet, writer, activist, and teacher Eli Clare says that curing his cerebral palsy would completely change who he is.3 “On an individual level, my cerebral palsy is defined as ‘trouble,’ both medically and culturally,” he said in an interview. “And yet, I don’t have any idea who I’d be without tremoring hands, slurring speech, tight muscles, and a rattling walk.”4

Clare isn’t against cures in principle. He makes a distinction between medical cures that save lives, reduce suffering, and prevent diseases, versus eradicating “perfectly imperfect” differences. The culprit is a cure mind-set that is embedded in popular culture. Thus we have weight-loss surgery, facial hair removal, Botox, teeth whitening, skin-lightening creams, and antidepressants, he said.5

Clare goes right to the heart of the matter in his latest book, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling With Cure.6 He says the search for perfection is frustrating, elusive, and dangerous, for everyone. He offers the idea of giftedness as an alternative. Giftedness means making the best with the knowledge, skills, and abilities you have. It doesn’t mean rejecting medical intervention when necessary. It does mean resisting the medicalization of identity. Professionals are always wanting to do something about his tremor, he says, when he all he wants is help for the tension that causes him chronic pain. Bodily differences are neither good nor bad, he says—just a simple fact of life. While acknowledging that there are those who want a cure and who want to reshape their bodies, he says the fact is that disability is more an issue of social justice than a medical condition. The cure mind-set “ignores the reality that many of us aren’t looking for cures but for civil rights,” he says, so that we live in a world where we assist each other.7

In the end, Clare wants “a politics that will help all of us come home to our bodies.”8

The Gift JUDITH SNOW

The Gift JUDITH SNOW

Everyone has a gift, including what others describe as a deficiency or disadvantage. Understanding that may one day save the human race.

Judith Snow was known as the Julia Roberts of the disability community even though she had a love-hate relationship with the word disability. “There is no such thing as disability,” she declared to audiences.9 She would invite them to reinterpret her wheelchair and the functional limitations associated with her disability. Her magnetic personality and penetrating intellect attracted loyal followers from around the world. Her objection to the D-word arose from the belief that everyone has a gift, including and especially what others saw as a deficit or a disadvantage. She described a gift as anything that creates a meaningful interaction with at least one other person.

She illustrated her meaning with a story from her high school years.10 A fellow student was a champion diver with the potential to become an Olympic medalist. The school and surrounding community went out of their way to nurture this young woman’s gift. They rearranged her classes, postponed her exams, and provided extra tutoring and coaching. Nothing was too daunting, too costly, or too inconvenient. Everyone wanted to play a part in the young diver’s success. They felt fulfilled. Some even got paid jobs out of it.

Snow, by contrast, had trouble even getting into the school building. There was no ramp, and there were no plans to build one. No extra tutoring. No accommodation. Those tasks were left to her parents, even though nurturing Judith’s scholarly abilities would have created similar opportunities for fulfillment and meaningful employment. Hurtling yourself headfirst into a swimming pool was a rare talent that happened to be valued, said Snow, whereas the fact that she could move only her thumb and the side of her mouth wasn’t, even though it had the same potential to nurture trust and bring meaning to the lives of others—more so, according to Snow’s fans.

Snow would often quote in her speeches the prophet Isaiah’s caution that if we do not welcome the gifts of strangers, society is doomed to slowly crumble. “I am both disabled and not disabled at the same time,” she said. “The question is, from which stance can I live my life most powerfully, both for myself and for the community? From which position am I more able to contribute? More able to experience a fulfilled life?”11

A Brief History of Imperfection DR. STEPHEN HAWKING

A Brief History of Imperfection DR. STEPHEN HAWKING

Staying curious, being nonjudgmental and open to changing your mind, is the true source of knowledge.

The theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking thrived on his failures, joked about his mistakes, and based his scientific theories on imperfection. “Next time someone complains that you have made a mistake, tell him that may be a good thing,” he said.12 He understood that failure and being wrong are just as important as scientific breakthroughs, psychological insight, or intellectual truth. It didn’t seem to matter whether he was right or wrong; both helped get him nearer and nearer to an understanding of the order of the universe. Hawking’s healthy skepticism, as well as his sense of humor about his discoveries and theories, got him into trouble with some of his colleagues. They believed that their particular scientific discovery was the end of the matter. They took exception to any suggestion that they could be wrong.

Hawking was twenty-two when he was diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a neurological condition that reduced his ability to control his muscles, including those he used for breathing. He was given a few years to live at the time. Instead, he lived another fifty years uncovering scientific secrets of the universe—discoveries he attributed to his disability. “My disabilities have not been a significant handicap in my field. . . . Indeed, they have helped me in a way by shielding me from lecturing and administrative work that I would otherwise have been involved in,” he wrote in an article about people with disabilities and science.13 His book A Brief History of Time became an international best seller because he used nontechnical language to describe his insights into what makes the universe tick. It was translated into more than thirty-five languages. When asked how he would design the universe differently, he replied, “If I had designed it differently, it wouldn’t have produced me. So that is a meaningless question. I’m prepared to make do with the universe we have, and try to find out what it is like.”14

Hawking turned being wrong and changing one’s mind from a weakness to a strength. He realized that no matter how much we know and how much we analyze and theorize, there are always more dark corners and black holes to expose to the light. “Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet,” he wrote. “Try to make sense of what you see, and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious.”15

If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Fix It THE SCHAPPELL TWINS

If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Fix It THE SCHAPPELL TWINS

Not everyone wants to get on the medical treatment train.

The Schappell twins couldn’t be more different:

Lori is outgoing. Dori is an introvert.

Lori is street-smart. Dori is book smart.

Lori worked in a laundry room; Dori was a country singer. She won an L.A. Music Award for Best New Country Artist in the 1990s. Her stage name was Reba, after her favorite singer, Reba McEntire.

Lori is able-bodied. Dori has spina bifida.

Lori drinks. Dori is a teetotaler.

Lori likes to spend money. Dori saves it—which is why Lori had to pay to get to see “Reba” perform.

There are a couple of things they agree on:

One is that they hate the rhyming names their parents gave them. So Dori, who identifies as a man, changed her name to George.

The other is that being a conjoined twin does not run their world. They are joined at the forehead but face in different directions. George has a specially designed chair, which is like a barstool on wheels. It’s just the right height for Lori to move him around; otherwise, she has to carry him. They believe their lives are less complicated than those of most people. They live in a two-bedroom flat and alternate the nights they sleep in each other’s rooms. When Lori goes on dates, George brings a book to read. Because they don’t face each other, he can ignore his sister’s kissing. “I don’t see why being a conjoined twin should stop me having a love life and feeling like a woman,” Lori said in an interview.16

George knew from a young age that he should have been a boy. “It was so tough, but I was getting older and I simply didn’t want to live a lie. I knew I had to live my life the way I wanted.”17 In response, Lori said, “Obviously it was a shock when Dori changed to George, but I am so proud of him. It was a huge decision but we have overcome so much in our lives and together we are such a strong team. Nothing can break that.”18

The twins have been the subject of numerous profiles. In one, the interviewer asked whether they would choose to be separated if the operation could be done safely. “Why would you want to do that?” replied George. “For all the money in China, why? You’d be ruining two lives in the process.”19

And when Lori was asked the same question in a documentary, her response was “No.”

“Why?” asked the interviewer.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” she replied.20

Hidden Wholeness PARKER PALMER

Hidden Wholeness PARKER PALMER

Embracing our imperfections makes us whole. Chasing perfection keeps us from becoming whole.

Parker J. Palmer is an acclaimed author of ten books on education, leadership, spirituality, courage, and social change. He has received thirteen honorary doctorates. He is considered one of the world’s leading visionaries.21 Yet he regards his greatest accomplishment to be surviving three serious bouts with clinical depression, two in his forties and one in his sixties. “Nothing I’ve ever done has required more fortitude and persistence than surviving that assault on my selfhood and sense of meaning and purpose in life,” he said in an interview.22

During those periods, Palmer spent months cowering in the darkness and had periods when he couldn’t feel anything at all, when it seemed his ego had been shattered. He knows he is not alone, and he is willing to write about it because depression is still a taboo subject. It has been estimated that one in ten Americans experiences clinical depression at some point in their lives.

Palmer considers himself a wounded healer. “I was born baffled and have trusted my bafflement more than my certainties,” he said in an interview.23 He knows everyone is a mixed bag. He believes the most important words he can offer to anyone who is suffering are “Welcome to the human race! Now you enter the company of those who have experienced some of the deepest things a human being can experience.”24

Palmer founded the Center for Courage & Renewal to close the gap between people’s personal and professional lives, and to help them integrate their inner and outer selves. He describes this in his book A Hidden Wholeness as a move toward wholeness. “Wholeness does not mean perfection,” he cautions, “it means embracing brokenness as an integral part of life.”25 For most people it is a hidden or forgotten wholeness. We compare ourselves with society’s image of perfection and find ourselves wanting. Instead, Palmer advises that we “put our arms lovingly around everything we’ve shown ourselves to be: self-serving and generous, spiteful and compassionate, cowardly and courageous, treacherous and trustworthy.” The only way to become whole is to say, “I am all of the above.”26 Perhaps this is the true meaning of integration.

Palmer’s mental illness taught him that there are no shortcuts to wholeness. It involves waiting, watching, listening, suffering, and honoring small signs of progress. “You work your way through that darkness, or it works its way through you.”27 It’s not easy to experience, and it’s not easy to watch someone else going through it, either. He suggests being present for another person’s pain without trying to fix it, and standing respectfully at the edge of his or her mystery—and misery.28

“When people ask me how it felt to emerge from depression,” he wrote in his book Let Your Life Speak, “I can give only one answer: I felt at home in my own skin, and at home on the face of the earth, for the first time.”29

Humanity Passport NAOKI HIGASHIDA WITH DAVID MITCHELL

Humanity Passport NAOKI HIGASHIDA WITH DAVID MITCHELL

Citizenship is a given and shouldn’t be based on what others consider normal.

Naoki Higashida wrote the Japanese best seller The Reason I Jump when he was thirteen. It has since been translated into thirty-four languages. It features his candid answers to fifty-eight questions about his autism. “Why don’t you make eye contact when you are talking?” “Why do you make a huge fuss over tiny mistakes?” And of course, “What’s the reason you jump?”

Higashida has now written twenty books, and he is not yet thirty. He doesn’t speak; he dictates his books by pointing to characters on a cardboard keyboard. A transcriber types them up. Videos of his creative process are available on YouTube. Talking is troublesome for Higashida. His mind goes blank whenever he tries to speak. “Spoken language is like a blue sea,” he wrote. “Everyone else is swimming, diving and frolicking freely, while I’m alone, stuck in a tiny boat, swayed from side to side.”30 However, when he’s working on his alphabet grid, he feels as if someone has cast a magic spell and turned him into a dolphin.

David Mitchell, the writer of the best seller Cloud Atlas, was so impressed with The Reason I Jump that he and his wife, Keiko Yoshida, translated it and Higashida’s follow-up book, Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8, into English. He said in an interview that the books helped him understand his own son’s behavior. “For the first time I had answers, not just theories. What I read helped me become a more enlightened, useful, prouder and happier dad,” he said.31 In another interview, Mitchell admitted that he didn’t have the imagination to afford his son “full card-carrying rights as a human being” until he read Higashida’s books. He said that Higashida’s writings are a “humanity passport” for people with autism because they challenge the myth that people with autism don’t have emotions, imagination, or dreams.32

Higashida said in an interview that it would be so much easier if the behavior of people with autism were regarded as another personality type. “What your child needs right now is to see your smile. Create lots of happy memories together. When we know we are loved, the courage we need to resist depression and sadness wells up from inside us.”33 On the other hand, he thinks neurotypical people agonize too much over being left out of the group, and that causes unnecessary conflict in their relationships. “I’ve learned that every human being, with or without disabilities, needs to strive to do their best, and by striving for happiness you will arrive at happiness,” he wrote in The Reason I Jump. “For us, you see, having autism is normal—so we can’t know for sure what your ‘normal’ is even like. But so long as we can learn to love ourselves, I’m not sure how much it matters whether we’re normal or autistic.”34

As for the reason he jumps, “When I’m jumping it’s as if my feelings are going upward to the sky. Really, my urge to be swallowed up by the sky is enough to make my heart quiver. When I’m jumping, I can feel my body parts really well, too—my bounding legs and my clapping hands—and that makes me feel so, so good.”35

A Culture with No Boundaries CAREY

, SHELLY, AND

ZOE ELVERUM

A Culture with No Boundaries CAREY

, SHELLY, AND

ZOE ELVERUM

Societal expectations change what’s wrong into what’s awesome.

When Carey and Shelly Elverum’s three-month-old daughter, Zoe, was diagnosed with dwarfism, they were in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. The medical specialists told them that “something went wrong.” When they returned home to Pond Inlet near the Arctic Circle, the reaction from the Inuit people who live there was “Hurray! That’s awesome.”36 Inuit elders considered Zoe a special being who should be raised by elders. Teenage girls wanted a baby like her. “Everywhere she was just treated as this wonderful being who had sprung into the middle of Pond Inlet,” said Shelly in an interview.37

Today Zoe is a typical teenager. She loves Star Wars and the color black. Her favorite Taylor Swift line is “If you are lucky enough to be different, don’t ever change.” She considers herself a NERD (Not Even Remotely Dorky). She is also student council vice president. “I’m getting more and more like my mom,” said Zoe, “speaking my mind and joining committees.”38

A big part of the whirlwind that is Zoe is due to the fact that she lives where she does, said her mom. “People’s perspective on dwarfism here is that she’s like concentrated orange juice. She is who she is because she hasn’t been diluted. So this whole community treats her as a really special, quality, capable person with something to contribute to the community.”39 As a result, Zoe has grown up with a healthy sense of herself, her mom said laughingly. “I’m like everyone else,” said Zoe. “Yeah, I know I’m smaller than everyone, but there are advantages to being smaller. I’m Zoe. To me I’m just me.”40

Did You Know . . .

One of the earliest representations of disability was the Greek god of fire, Hephaestus. To the Romans he was Vulcan. Accounts vary as to the origin of his physical disability. It occurred either at birth or because his foot was permanently injured after he was thrown off Mount Olympus by his mother, Hera, queen of the gods. The only god who worked, he was a master artisan, talented blacksmith, and sculptor. He designed Hermes’ winged helmet, Aphrodite’s girdle, and Achilles’ shield. He also designed a winged chariot to assist him in moving around, the forerunner of today’s wheelchair.

Did You Know . . .

Virginia Hall was an American-born spy who worked for the British in occupied France during World War II. She lost her leg in a shooting accident. The Germans considered “the spy with the wooden leg” to be the most dangerous of all Allied spies. They launched a hunt across France to find and destroy “the limping lady.” For her bravery she was made an honorary member of the British Empire. She received the US Army’s Distinguished Service Cross, the only one awarded to a civilian woman in World War II.