1

The Motivation Dilemma

Larry Lucchino found himself in an envious position. He had the perfect person in mind to recruit and hire as a new employee at the highest salary ever paid to someone in the role. He was authorized to include whatever it might take to motivate this person to work in his organization—signing bonus, moving allowance, transportation, housing, performance bonuses, and a high-status office.

Lucchino’s mission: lure Billy Beane, the general manager of the small-market Oakland A’s, to the Boston Red Sox, one of the most storied and prestigious franchises in baseball. Lucchino was impressed with Billy’s innovative ideas about using SABRmetrics—a new statistical analysis for recruiting and developing players.

In 2002, the Red Sox offered Billy what was at the time the highest salary for a GM in baseball’s history. The team enticed him with private jets and other extravagant perks. As you may know from Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game or from the hit movie starring Brad Pitt, Billy turned down the historic offer.

Billy’s mom, Maril Adrian, one of my dearest friends, shared her perspective with me in real time as Billy’s life unfolded in the media over the decade. She told me that Billy’s values inspired his choices—especially his dedication to family and love of baseball.

Sports Illustrated corroborated her assertion: “After high school, Beane signed with the New York Mets based solely on money and later regretted it. That played into his decision this time.”1

Every day, managers make the same mistake Lucchino made: they believe they can motivate people. It’s not all the managers’ fault. Armed with antiquated ideas about motivation, most organizations hold managers accountable for motivating people.

The motivation dilemma is that you are being held accountable for something you cannot do: motivate people.

Attempting to motivate people is a losing proposition, no matter your resources. Why? Because people are already motivated—but maybe not in the way you want. When you assume people aren’t motivated, you tend to fall back to strategies proven ineffective, wrongheaded, or even counter to what you intended. You incentivize, and when that doesn’t work, you add more carrots (rewards, incentives, bribes). When you run out of carrots, you may try wielding a thicker stick (threats, fearmongering, and punishment). At some point, you realize your attempts to motivate people are fruitless or, even worse, more harmful than beneficial.

The motivation dilemma begins with an erroneous premise—assuming people aren’t motivated and the leader’s job is to motivate them. I was sharing this idea with a group of managers in China when a man yelled, “Shocking! This is shocking!” Startled, we all jumped. It was highly unusual for a participant to yell out loud in a typically reserved audience. I asked him, “Why is this so shocking?” He replied, “My whole career, I have been told my job as a manager is to motivate my people. I have been held accountable for motivating my people. Now you tell me I cannot do it.” “That’s right,” I told him. “So how does that make you feel?” “Shocked!” he repeated before adding, “And relieved.”

I have witnessed an epiphany among managers and human resource professionals as they realize that depending on carrots and sticks is a flawed strategy to get people to pursue goals, adopt new habits, or change behavior. They recognize that they’ve been relying on old-fashioned methods without the benefit of empirical science that proves these strategies undermine the type of motivation needed for people to achieve results while simultaneously experiencing well-being.

Let go of the notion that you can and should motivate people.

Letting go of traditional approaches to motivation used to be challenging because we didn’t understand the true nature of human motivation and the alternatives for tapping into people’s natural vitality. Now we do.

Model That Reflects Reality: The Spectrum of Motivation

Traditional motivation approaches ask if people are motivated or not. But that’s the wrong question. The question isn’t even what motivates people. Lucchino and the Red Sox suspected Billy wasn’t inclined to take a new job or move to the East Coast. They depended on traditional means to try to motivate—or manipulate—him. They might have discovered why he rejected their offer if they had understood that Billy was already motivated. They could have uncovered the reasons guiding Billy’s choices.

People are always motivated. The crucial question is why.

People are always motivated. The crucial question is why.

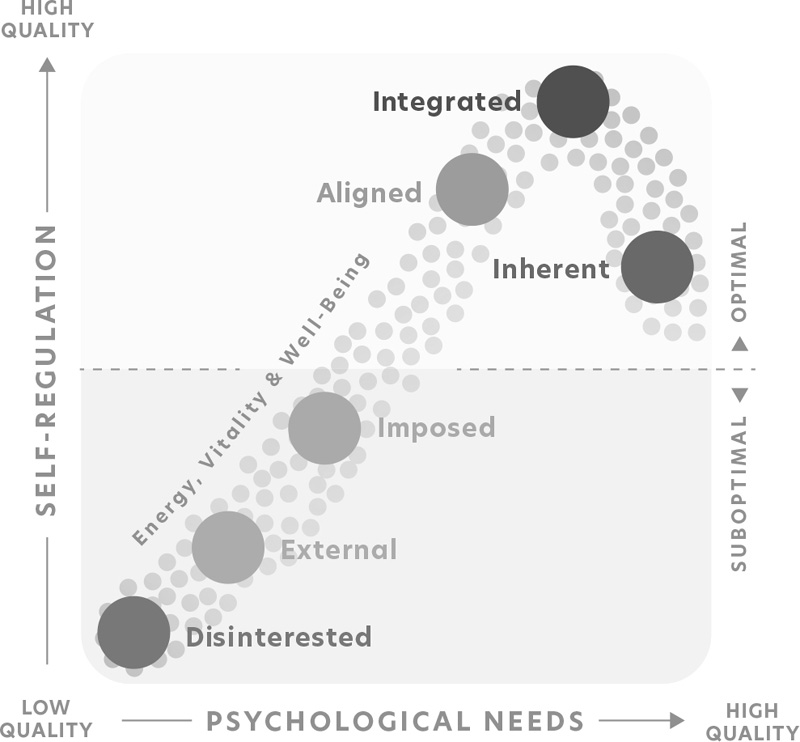

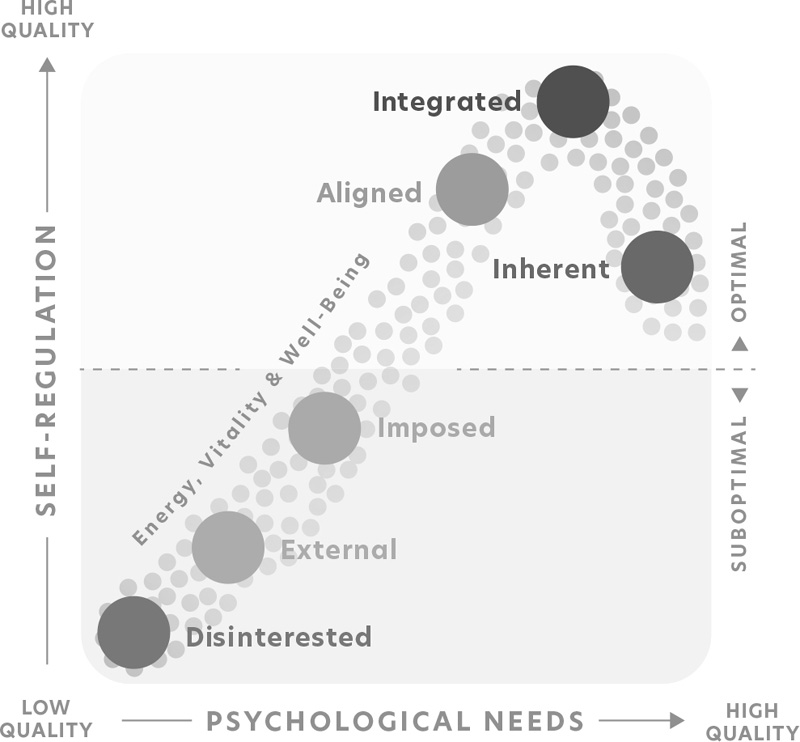

I’m willing to bet that when facilitating a team meeting, you know it’s a mistake to assume that participants are motivated to be there just because they show up. But it’s also a mistake to think they are unmotivated if they check their phones during the meeting. A more accurate and valuable conclusion is that everyone attending is motivated but not for the same reasons. Asking why people are motivated to be at your meeting leads to a spectrum of motivation possibilities represented as six motivational outlooks in the Spectrum of Motivation model, figure 1.1.2

The model reflects the reasons people do what they do. The six motivational outlooks describe six types of motivation or different reasons people might take action (or not). If we use the meeting as an example, notice how people can exhibit the same behavior (participate in the meeting) for different reasons that affect the quality of their energy:

• Disinterested motivational outlook—They show up and go through the motions, even though they cannot find any value in the meeting; it feels like a waste of time, or they are so busy that attending adds to their sense of feeling overwhelmed.

• External motivational outlook—The meeting is an opportunity to demonstrate their power or status, which could also lead to more money or promotion in the future; attending is a chance to earn badges, kudos, or even a bonus or financial perk.

• Imposed motivational outlook—They feel pressure to attend because everyone else is attending, they fear what might happen if they don’t show up, or they hope their attendance will help them avoid feeling guilt, shame, or a sense that they’ve disappointed you.

• Aligned motivational outlook—They attend because they believe the meeting aligns with a significant personal value, such as learning; they feel attending is the right thing to do.

• Integrated motivational outlook—They link the meeting to their life or work purpose, such as giving voice to a meaningful issue; they self-identify with the reason for the meeting in a meaningful way (“I’m a sales leader, and this is what sales leaders do”).

• Inherent motivational outlook—They simply enjoy meetings and thought it would be fun.

FIGURE 1.1 Spectrum of Motivation model—six motivational outlooks

The outlooks are not on a continuum. Someone might experience one outlook when the meeting appears on their calendar, another as they walk into the room, and another depending on the discussed topic. Different motivational outlooks can pop up anytime, hence the model’s bubbles.

Recognizing the six motivational outlooks is essential to effective leadership, but you must also appreciate why the Spectrum of Motivation has two halves.

The distinction between suboptimal and optimal motivation captures the chasm between traditional thinking and the new science of motivation:

• Three outlooks—disinterested, external, and imposed—are considered suboptimal. Outdated motivational theories revolve around suboptimal outlooks that reflect low-quality motivation. These outlooks represent motivational junk food that fails to generate positive energy, vitality, and a sense of well-being.

• Three outlooks—aligned, integrated, and inherent—are considered optimal. The new motivation science revolves around optimal outlooks that reflect high-quality motivation. Optimal outlooks represent motivational health food that generates the positive energy, vitality, and sense of well-being required to sustain the pursuit and achievement of meaningful goals while thriving and flourishing.

Appreciating how suboptimal and optimal motivational outlooks affect people’s well-being, short-term productivity, and long-term performance is essential to leading at a higher level.

The distinction between suboptimal and optimal motivation captures the chasm between traditional thinking and the new science of motivation.

The Downside of Motivational Junk Food

Consider this scenario. You buy dinner at a local drive-through—burgers, fries, and shakes—planning to eat at home with your family. But the aroma of those fries is intoxicating. You simply cannot help yourself—you eat one. By the time you arrive home, the bag of french fries is empty.

How do you feel after downing the package of french fries? Guilty or remorseful? Consider the effect junk food has on your mental energy. What happens to your physical energy even if you feel grateful and satisfied? It spikes dramatically and falls just as dramatically. How nourished is your body? A steady diet of junk food simply isn’t good for you. Even if you can justify an occasional splurge, you are wise to understand your choices.

Suboptimal motivation is the equivalent of motivational junk food. When you entice people by promising more money, awarding prizes, offering rewards and badges, threatening punishment, applying pressure, and imposing guilt, shame, or emotional blackmail, you’re offering them a motivational junk-food buffet. Using suboptimal motivational tactics to encourage specific behaviors from people has the same short- and long-term effects on their psychological health as junk food has on their physical health. Unfortunately, people find these rewards and punishments (carrots and sticks) as hard to resist as french fries.

Here’s a too-common scenario. Your HR department sends employees an invitation to enter an incentive program. If they lose enough weight, they win an iPad. They think, “What do I have to lose except some weight? What do I have to gain except health and an iPad?” They should think again.

Researchers followed people who entered an organization-sponsored contest awarding prizes for losing weight.3 They found that many people lost weight and won rewards. However, the studies were conducted only during the contest period. They didn’t track maintenance. The research that incentive companies use to sell their extrinsic reward programs to organizations ends here, concluding that such programs are effective for helping people lose weight. The rest of the story is one that too many leaders and HR professionals have not heard.

If people participate, without perceived pressure, in a behavior-change program offering small financial incentives, they may be likely to change their behavior initially. But when researchers continue following the prizewinners after an incentive program ends, their findings mirror what extensive motivational research has proven about incentives: twelve weeks after winning their prize, people resume old behaviors, regain their lost weight, and add even more weight.4

Study after study verifies that tangible incentives do not sustain changes in personal health behaviors but undermine those behaviors over time. A heavy dose of motivational junk food might help people initiate new and healthy behaviors but fails miserably in assisting people to maintain their progress or sustain results. What may be more disturbing is that people are so discouraged, disillusioned, and debilitated by their failure that they are less likely to engage in further weight-loss attempts. If they do, they might game the system by going through the motions to get their reward but not expecting lasting change.

These extrinsically based schemes cost more than people realize: the participants’ failure in one area of their life can affect their sense of efficacy in other areas. So why do over 70 percent of wellness programs in the United States use financial incentives and rewards programs to encourage healthy behavior changes?5 The reasons below can apply to any incentive-based motivation scheme:

• Financial incentives, rewards, badges, and tokens are easy (if expensive) to offer.

• Organizations have not taken the time to create more innovative, healthy, and sustainable options.

• People feel entitled to receive incentives, and organizations are afraid to take them away.

• Leaders promote junk-food motivation to entice people to achieve goals or adopt certain behaviors because they simply don’t question standard practices.

• Leaders have not learned how to facilitate people’s shift to a more optimal and sustainable motivational outlook.

• People don’t understand the nature of their motivation, so when they are unhappy at work, they ask for more money. They yearn for something different—but they don’t know what it is—so they ask for the most apparent incentive: money or perks. Managers assume that their hands are tied because they can’t comply with someone’s request for more money.6

The Upside of Motivational Health Food

Kacey is perennially a top salesperson in her organization. She felt offended when her company announced a contest to award top sellers with a weeklong spa trip. “Do they think I do what I do so I can win a week at a spa? Maybe it sounds corny, but I work hard because I love what I do. I get great satisfaction from solving my clients’ problems and seeing the difference it makes. If my company wants to connect with me and show appreciation, that’s different. That isn’t the case. If they knew me, they would understand that as a single mother, a spa week away is not a reward but an imposition.”

People with high-quality motivation, such as Kacey, may accept external rewards when offered, but this is not the reason for their efforts. The reasons the Kaceys of the world do what they do are more profound and provide more satisfaction than external rewards can deliver.

Kacey would have found it easier if her organization had been more attuned to her needs rather than falling into the junk-food belief that salespeople are motivated by money and rewards. Instead, she found herself in an awkward situation. Kacey didn’t want to get sucked into the low-quality motivation of the reward trip. Still, she feared offending her manager and colleagues by refusing the trip or complaining about the options.

Being an exemplary self leader, Kacey initiated a meeting with her manager to discuss the situation. She explained how the incentive program had the opposite effect than her manager had probably intended. She declared that she would continue selling and servicing her customers with her usual high standards—regardless of winning a reward. Kacey and her manager both described the conversation as “liberating.” They felt it deepened their relationship because the manager now understood Kacey’s internal dedication to her work.

At the end of the next sales cycle, Kacey exceeded her goals based on her own high-quality reasons. Instead of imposing a reward on her, Kacey’s manager conferred with her about how he could express his gratitude for her achievements within fair price and time boundaries. Kacey chose an activity that she and her young child could enjoy together. Rather than interpreting the reward trip as a carrot to work harder, Kacey interpreted it as an expression of her organization’s gratitude. She reported how different the experience was from previous award trips: “The week took on special significance as a heartfelt thank-you from my manager and a wonderful memory-making experience with my child.”

Kacey’s deepened relationship with her manager and feeling valued were far more rewarding than winning a contest. When people experience high-quality motivation, the implications for the organization are significant. They achieve above-standard results; demonstrate enhanced creativity, collaboration, and productivity; are more likely to repeat their peak performance; and enjoy increased physical and mental health.7

Junk Food or Health Food—You Choose

The three suboptimal motivational outlooks—disinterested, external, and imposed—are the junk foods of motivation. Their tangible or intangible rewards can be enticing at the moment but do not lead to flourishing—far from it. People with a sub-optimal motivational outlook are less likely to have the energy it takes to achieve their goals. But even if they do, they are less likely to experience the positive energy, vitality, or sense of well-being required to sustain their performance over time.8

The three optimal motivational outlooks—aligned, integrated, and inherent—are the health foods of motivation. They may require more thought and preparation, but they generate the high-quality energy, vitality, and positive well-being that lead to sustainable results.

Case in Point: Himesh and the Lab Tech

On his first day back at a plant in India, after a training session on the Spectrum of Motivation, Himesh encountered one of his employees with low-quality motivation.9

Himesh noticed his technical service executive discussing something with an external contractor in the lab. Himesh saw that the technician was wearing safety glasses, but she had not followed plant procedures to ensure the contractor was also protected.

Himesh is a strict manager with a no-tolerance policy regarding breaking safety regulations. His typical response to this flagrant breach of policy would be to call the technician to his office and, in his words, “read her the riot act.” By the way, this is why Himesh had been in the training class. His plant’s engagement scores were among the lowest in a global company with more than fifty thousand employees.

According to Himesh’s self-assessment, “I am known to blow a fuse (or two) when people flout safety rules. However, I managed to keep my cool and decided to test my training.” He asked the technician to come to his office. He could see that she was worried about his reaction. Instead of leading with his dismay and disappointment, Himesh started by explaining that he had just received some training on motivation. He shared core concepts with her. He then asked her if she thought the rule to wear safety glasses when no experiment was happening was stupid, as there is no danger to the eyes. Did she feel imposed upon by having to wear safety glasses at all times?

Since Himesh had invited the technician to have a discussion rather than a dressing down, she was open and candid. She explained that she had a two-year-old child and was highly concerned about lab safety, as she wanted to reach home safe every evening. To Himesh’s surprise, she also shared that she would prefer even more stringent safety measures in certain areas. For example, she suggested they require safety shoes for lab experiments conducted at elevated temperatures. But she could not understand the rationale for wearing safety glasses when no one was conducting experiments. Indeed, the technician expressed her resentment about the imposed rule. She didn’t feel compelled to enforce it, especially with an external contractor.

Himesh listened and genuinely acknowledged her feelings. He then provided his rationale behind the regulation, explaining his hope and intention that wearing glasses would become a habit that protects people’s lives, just like wearing a safety belt in the car.

Himesh said, “I saw the light dawn in her eyes.”

It is important to note that Himesh did not attempt to motivate the technician. He recognized that she was already motivated. She was motivated not to follow the regulation. He challenged his natural tendency to rush to judgment and took the time to explore why she was motivated the way she was. By understanding the nature of her motivation, he had more options on how to lead.

He reported: “I am sure if I had followed my normal instincts and given her a piece of my mind, I would have been met with a hangdog look, profuse apologies, and a promise to never do this again. And it probably would have happened again. She would have gone away from my office with feelings of resentment and being imposed upon, and I would also have had a disturbed day due to all the negative energy.”

Himesh’s approach helped his technician shift her motivation from low quality (imposed outlook) to higher quality (aligned outlook). As he reported, “Suffice it to say that in my view, my little experiment was a success. I have shared what I learned with many of my team members and I plan to have more motivational outlook conversations with them in the coming weeks.”

Recapping “The Motivation Dilemma”

The motivation dilemma is that even though motivating people doesn’t work, leaders are held accountable for doing it. This dilemma has led to ineffective motivational leadership practices. Traditional motivational tactics focus on obtaining short-term results. Pushing for results, you discover that pressure, tension, and external drives prevent people from attaining those results. Even short-term gains can’t compare to the loss of creativity, innovation, physical health, and mental well-being. Adding insult to injury, suboptimal motivation all but destroys long-term prospects.

Motivating people does not work because they are already motivated—they are always motivated in one of the six ways reflected in the Spectrum of Motivation. So if motivating people doesn’t work, what does? The next chapter reveals alternatives to motivational junk food and the healthy options that could be the answer to your motivation dilemma.