Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Practicing Positive Leadership

Tools and Techniques That Create Extraordinary Results

Kim Cameron (Author)

Publication date: 08/07/2013

Plenty of research has been done on why companies go terribly wrong, but what makes companies go spectacularly right? That's the question that Kim Cameron asked over a decade ago. Since then, Cameron and his colleagues have uncovered the principles and practices that set extraordinarily effective organizations apart from the merely successful.

In his previous book Positive Leadership, Cameron identified four strategies that enable these organizations, and the individuals within them, to flourish: creating a positive climate, positive relationships, positive communication, and positive meaning. Here he lays out specific tactics for implementing them. These are not feel-good nostrums—study after study (some cited in this book) have proven positive leadership delivers breakthrough bottom-line results. Thanks to Cameron's concise how-to guide, now any organization can be “positively deviant,” achieving outcomes that far surpass the norm.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Plenty of research has been done on why companies go terribly wrong, but what makes companies go spectacularly right? That's the question that Kim Cameron asked over a decade ago. Since then, Cameron and his colleagues have uncovered the principles and practices that set extraordinarily effective organizations apart from the merely successful.

In his previous book Positive Leadership, Cameron identified four strategies that enable these organizations, and the individuals within them, to flourish: creating a positive climate, positive relationships, positive communication, and positive meaning. Here he lays out specific tactics for implementing them. These are not feel-good nostrums—study after study (some cited in this book) have proven positive leadership delivers breakthrough bottom-line results. Thanks to Cameron's concise how-to guide, now any organization can be “positively deviant,” achieving outcomes that far surpass the norm.

—Brent Dunsford, Chief of Staff, Government Business, Humana

“Dr. Cameron's fresh insights and innovative approaches to leadership have given me and my senior managers new ways to inspire and lead our line managers and staff toward producing their best work.”

—Julie Zawisza, Director of Office of Communications, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration

“Making the decision to focus my energy on positive situations has led to increased staff morale, higher student achievement, and greater productivity… the impact of positive leadership can change lives.”

—Scot A. Graden, Superintendent, Saline Area Schools, Saline, Michigan

1 Why Practice Positive Leadership?

2 How to Create a Culture of Abundance

3 How to Develop Positive Energy Networks

4 How to Deliver Negative Feedback Positively

5 How to Establish and Achieve Everest Goals

6 How to Apply Positive Leadership in Organizations

7 A Brief Summary of Positive Leadership Practices

Notes

Practicing Positive Leadership

Self-Assessment

References

Index

1

WHY PRACTICE POSITIVE LEADERSHIP?

The University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business recently announced a new strategic plan to guide business education through the next decade and beyond. A key strategic pillar is an emphasis on the positive—positive business, positive leadership, and making a positive difference in the world.

Humana, one of the largest health insurance providers in the United States, recently changed its identity from being an insurance company to being a well-being company. The primary objective is to create benefits for employees and customers by implementing practices based on positive leadership and positive organizational scholarship.

Toshi Harada, Director of International Business Development at Hayes Lemmertz—the world’s largest producer of automobile wheels—equates positive leadership with Japanese manufacturing principles. “A signature feature of Japanese manufacturing philosophy is the elimination of waste. Negative leaders represent waste and inefficiency,” he suggests, “whereas positive leadership produces sustainable improvement.” 1

Jim Mallozzi, former CEO of one of the Prudential Financial Services businesses, turned around the financial performance in his organization by providing his top team “the latitude to experiment on being positively deviant leaders.” Financial results changed in one year from a $140 million loss to a $20 million profit through applying practices of positive leadership. 2

George Mason University has recently engaged in an institution-wide effort to become the world’s first well-being university by, among other things, integrating positive leadership practices throughout the entire system. Both top-down and bottom-up interventions are being initiated.

Producing extraordinarily high performance, generating positively deviant results, and creating remarkable vitality in the workplace are the primary objectives of positive leadership. Positive leadership involves the implementation of multiple positive practices that help individuals and organizations achieve their highest potential, flourish at work, experience elevating energy, and reach levels of effectiveness difficult to attain otherwise. The practices included in this book can help produce such extraordinarily positive results.

Empirical research by recent scholars, as well as anecdotal evidence such as the examples described above, confirms that positive leadership practices produce results that exceed normal or expected performance. And while the evidence that positive leadership brings improvement in organizational productivity, profitability, quality, innovation, and customer loyalty might not be unexpected, many may be surprised to learn that there is published evidence that this revolutionary approach to leading and managing produces benefits in terms of individual physiological health, emotional well-being, brain functioning, interpersonal relationships, and learning as well. 3

Lingering questions have been raised regarding positive leadership, such as: Exactly how are these results achieved? What tools or techniques can managers implement to obtain positive results in their organizations? What specifically can leaders do to practice positive leadership? This book will show you. It builds on and supplements my previous book Positive Leadership. That earlier work provided evidence showing how four positive leadership strategies—that create a positive climate, positive relationships, positive communication, and positive meaning—can produce exceptional results.

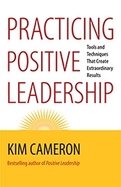

Here I present specific practices and activities that can serve as guides for implementing those four positive leadership strategies. As Figure 1 shows, each of the practices (in the box corners) interacts with more than one of the leadership strategies (in darker-colored ovals). The figure illustrates the relationships among the positive leadership practices presented in this book and the four strategies in the Positive Leadership book.

Throughout the book I will summarize empirical research that has established the validity of the practices and discuss how real organizations have successfully applied them to produce positive results. 4 Activities are provided in each chapter so that you can immediately implement the practices in your own organizations.

FIGURE 1

Relationships Between Positive Leadership Practices and Positive Strategies

POSITIVE LEADERSHIP IS HELIOTROPIC

Practicing positive leadership is important because positivity is heliotropic. That is, all living systems have a tendency to move toward positive energy and away from negative energy, or toward what is life-giving and away from what is life-depleting. 5 One form in which we experience positive energy in nature is sunlight. In human interactions, it often takes the form of interpersonal kindness and gratitude. Positive leadership practices engender positive energy and unlock resources in people because, like all biological systems, human beings possess inherent inclinations toward the positive.

You can see examples of the heliotropic effect in both individuals and organizations. 6 For instance, people are more accurate in processing positive information—whether the task involves verbal discrimination, organizational behavior, or judging emotion—than negative information. People reported thinking about positive statements 20 percent longer than negative statements and almost 50 percent longer than neutral statements, and positive information can be recalled more easily and more accurately than negative information. People more effectively learn and remember positive terms and events than neutral or negative ones: when presented with lists of positive, neutral, and negative words, for example, people are more accurate in recalling the positive, and the longer the delay between learning and recalling, the more positive bias is displayed. Managers are much more accurate in rating subordinates’ competencies and proficiencies when the subordinates perform correctly than when they perform incorrectly.

We tend to seek out positive stimuli and avoid negative stimuli, as evidenced by people’s judgments that from two-thirds to three-quarters of the events in their lives are positive. Further, most people say they are positive, optimistic, and happy most of the time. Positive words have higher frequencies in all the languages that have been studied to date, and positive words typically entered English usage more than 150 years before their negative opposites (for example, “better” entered before “worse”). Central nervous system functioning (i.e., vagus nerve health) is most effective, the density of the brain’s gray matter is enhanced, and coherence of bodily rhythms is at its peak when people experience positive and virtuous conditions compared to neutral or negative conditions. 7

Several studies have highlighted how being exposed to positive influences increases life expectancy. Pressman and Cohen, for example, examined the journals of famous psychologists of the past and counted the positive and negative words used in their writing. Psychologists whose writings used a greater number of positive words lived an average of six to seven years longer than their more negative colleagues. 8 Pressman also studied famous singers and found that those who sang love songs with positive words lived an average of fourteen years longer than those who sang love songs with angry words. (Interestingly, the content of the song did not affect the life expectancy of the person who wrote the song, only that of the person who repeatedly sang the song.) 9 Snowden’s well-known study of 678 Catholic nuns also found that those using the greatest number of positive words in their journals and autobiographical essays when they entered the convent lived an average of twelve years longer than their counterparts. 10

A bias toward the positive, in other words, characterizes human beings in their thoughts, judgments, emotions, language, interactions, and physiological functioning. It is natural for humans to incline toward the positive, and empirical evidence suggests that positivity is the preferred and natural state of human beings, just as it is among other biological systems. Positive leadership practices promote a heliotropic effect, helping people to move toward the positive.

YEAH, BUT NEGATIVE DOMINATES POSITIVE

On the other hand, a great deal of evidence also exists that human beings react more strongly to the negative than to the positive. 11 Negative news sells more newspapers than positive news, people pay more attention to critical comments than to compliments, and traumatic events have greater impact than positive ones. All living systems react strongly and quickly to threats to their existence or signals of maladaptation.

For example, the effects of negative information and negative events take longer to wear off than the effects of positive information or pleasant events. A single traumatic experience (e.g., abuse, violence) can overcome the effects of many positive events, but a single positive event does not usually overcome the effects of even a single traumatic event. A positive event is remembered more accurately and longer, but a negative event has more effect on immediate memory and salience in the short run. Negative events have a greater effect on people’s subsequent moods and adjustments than positive events, and negative or upsetting social interactions weigh more heavily on people than positive or helpful interactions, often producing depression or bad moods. People tend to spend more time thinking about threatening personal relationships than about supportive ones, and about personal goals that were blocked compared to those that were not blocked. When negative things happen (for example, people lose a wager, endure abuse, or become a victim of a crime), they spend more time trying to explain the outcome or to make sense of it than when a positive outcome occurs.

In human interactions, undesirable human traits receive more weight in impression formation than desirable traits. Bad reputations are easy to acquire but difficult to lose, whereas good reputations are difficult to acquire but easy to lose. In initial hiring decisions, 3.8 unfavorable bits of information are required to shift an initial positive decision to rejection, whereas 8.8 favorable pieces of information are necessary to shift an initial negative decision to acceptance. To be categorized as good, for example, one has to be good all the time, but to be categorized as bad, one only has to engage in a few bad acts.

Events that are negatively valenced (e.g., losing money, being abandoned by friends, and receiving criticism) will have a greater impact on the individual than positively valenced events of the same type (e.g., winning money, gaining friends, and receiving praise). This is not to say that bad will always triumph over good, spelling doom and misery to the human race. Rather, good may prevail over bad by superior force of numbers: Many good events can overcome the psychological effects of a single bad one. When equal measures of good and bad are present, however, the psychological effects of bad ones outweigh those of the good ones. 12

An important function of positive leadership, therefore, is to demonstrate tools, techniques, and practices that can overcome the effects of the negative. When positive practices are given greater emphasis than negative practices, individuals and organizations tend to flourish.

POSITIVE LEADERSHIP AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Individual effects are not the same as organizational effects, of course. In organizations, leaders must address multiple constituencies. Processes, routines, and structures must be considered. Cultures, embedded values, and traditions must be respected. Employee preferences and relationships must be taken into account. An important question, therefore, is whether positive practices produce positive outcomes in organizations as they do in individuals.

In the last decade, substantial empirical evidence has demonstrated that positive leadership practices produce good outcomes in organizations, just as positivity does with individuals. Studies in several industries and sectors have shown, for example, that organizations that implemented positive practices increased their profitability, productivity, quality, customer satisfaction, and employee retention. 13

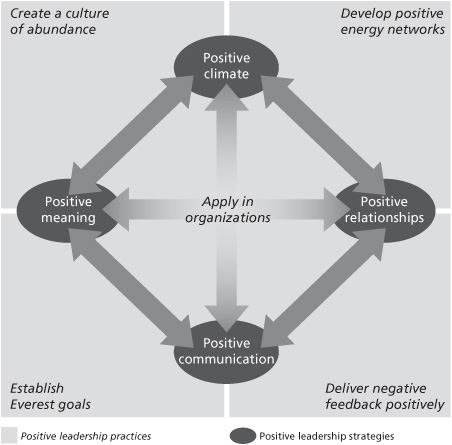

One early study, for example, assessed positive practices and outcomes in seven organizations in the transportation industry. The results (shown in Figure 2) suggest that the greater the positive practices in these firms, the higher the organizational performance on six dimensions—profitability, productivity, quality, innovation, customer satisfaction, and employee retention. This study was then expanded to include organizations across sixteen different industries and included both for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. The organizations studied encompassed both large firms such as General Electric, National City Bank, and OfficeMax as well as small and not-for-profit firms such as the YMCA, hospitals, and educational organizations. The results matched those in Figure 2: organizations that implemented positive practices were significantly more effective than organizations that did not.

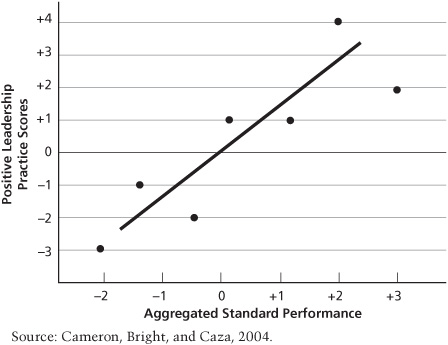

Another investigation was conducted in the U.S. airline industry following the tragedy of September 11, 2001. After the World Trade Center towers came down and the Pentagon was attacked, all flights were suspended for several days. When the airlines were allowed to fly passengers again, ridership topped out at 80 percent of previous ridership levels. The problem is, the economic model of the U.S. airline industry was based on an 86 percent seat-fill rate, so all of the airlines had substantial excess capacity and costs. Figure 3 shows the amount of downsizing implemented by each company.

FIGURE 2

Firm Performance and Positive Leadership Practices

Each airline approached downsizing and cost cutting in a different way. Some approaches were more consistent with positive leadership practices than others For example, US Airways responded by downsizing more than 20 percent and by declaring financial exigency, which meant that it could lay off employees with no benefits and no severance and that union contracts were rendered null and void. Southwest Airlines, on the other hand, laid off no one: “You want to show your people that you value them, and that you aren’t going to hurt them just to get a little more money in the short run. Not furloughing people breeds loyalty. It breeds a sense of security. It breeds a sense of trust.” 14

FIGURE 3

Relationship Between Downsizing by U.S. Airline Companies after 9-11 and Financial Return September 2001–2002

The problem is that failing to reduce the number of employees and lower the associated costs can put the airline company’s viability at risk. Stockholders and investors are impervious to how employees are treated. Wall Street has just one goal: provide a return on investment. This might suggest that Southwest Airlines would be punished severely by Wall Street investors for its refusal to cut jobs.

Nine airline companies were distinguished in terms of the extent to which they followed practices of positive leadership in their approach to downsizing. Some did so in a way that preserved the dignity, financial support, and safety nets of employees, while others did not. As illustrated in Figure 3, the correlation between stock price or financial return to these companies in the following twelve months and the extent to which they consistently utilized positive leadership practices is .86. Firms that implemented positive leadership practices made significantly more money and recovered more quickly than those that did not. 15

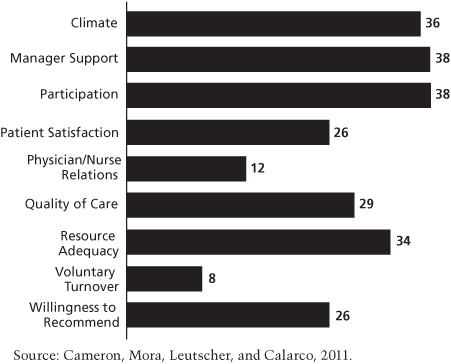

Two additional studies—one investigating forty financial services organizations and one looking at thirty health care organizations—produced similar results. In those studies, performance improvements over a multi-year period were examined to determine the relationship between positive leadership and organizational performance. Positive leadership practices were measured over a two-year period, and then a year later performance was measured. In both industries, when positive leadership practices were implemented, performance scores also improved significantly. Figure 4 shows the health care organizations’ outcomes after positive leadership practices were implemented: double-digit improvement occurred on a variety of performance dimensions. 16

These studies clearly show that positive leadership practices can produce significant improvement in all types of organizations. The practices introduced in this book have been implemented in organizations across several industries, including health care, the military, government, education, financial services, manufacturing, and retail. Their usefulness is not limited to a particular sector or type of organization.

FIGURE 4

Percent Improvement in Health Care Over Two Years

POSITIVE LEADERSHIP PRACTICES, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUES

Chapter 2, “How to Create a Culture of Abundance,” details five specific steps aimed at organizational culture change. The first step focuses on creating readiness for culture change—for example, by identifying standards for comparison and by altering language and symbols. All change is accompanied by resistance, so the second step discusses tools and techniques for overcoming resistance. When readiness has been created and resistance reduced, people need to know what the new culture will be like, so the third step involves articulating a vision of abundance. A vision of abundance always contains both left brain and right brain attributes. The fourth step features activities that will generate commitment to the vision and to the new culture. Commitment and participation are highly related. The fifth step, fostering sustainability, ensures that the culture of abundance will become institutionalized and can be sustained over time.

It is almost impossible to be a positive leader without also being a source of positive energy. Therefore, Chapter 3, “How to Develop Positive Energy Networks,” summarizes the evidence showing that positively energizing leaders create remarkable performance in other people and in their organizations. The chapter also provides several specific tools and techniques for developing positive energy that have been successfully applied in a variety of settings. These include practices associated with recreational work, contribution activities, and mapping energy networks.

Positive leadership does not mean constant smiling and sweet interactions. Sometimes positive leaders must deliver negative messages, address problems, or tackle difficult issues. Chapter 4, “How to Deliver Negative Feedback Positively,” guides leaders through a series of tools, techniques, and practices that help build and strengthen relationships even though corrective or disapproving feedback must be delivered. Practices for being critical without producing defensiveness, bruising egos, or invalidating opposing points of view are highlighted.

Goal setting is a very common technique for motivating performance and for maintaining accountability. Chapter 5, “How to Establish and Achieve Everest Goals,” highlights the differences between normal goal setting and identifying Everest goals. Everest goals possess the same attributes as the better-known SMART goals—both types are specific, measurable, aligned, realistic, and time-bound—but Everest goals possess five additional attributes that make them unique. They are associated with positive deviance—extraordinarily positive and even virtuous performance; they are associated with inherent value; they possess an affirmative orientation rather than a problem-solving orientation; they aim to provide a contribution regardless of personal benefit; and they create and foster sustainable positive energy. This chapter provides ways to identify and work toward the achievement of both individual and organizational Everest goals.

Positive leadership most often occurs in the context of an organization, and what works in interpersonal interactions may not necessarily work the same way in organizational contexts. Organizational dynamics frequently introduce complexities, competing values, and the need for trade-offs. In Chapter 6, “How to Apply Positive Leadership in Organizations,” the Competing Values Framework is briefly introduced and is used to demonstrate different types of tools and techniques for implementing positive leadership in organizational settings. The criticism that positive leadership emphasizes kindness and gentleness at the expense of the hard-nosed, competitive, challenging aspects of leadership is countered in this chapter. Tools and practices are introduced that address both the soft and the hard side of leadership.

CONCLUSION

This book provides a variety of tools, techniques, and practices that supplement rather than duplicate the more commonly prescribed self-help prescriptions. The practices described here all meet three criteria: they have been confirmed by valid empirical research, they are grounded in theory, and they have been applied in a range of organizational settings. Each practice has helped positive leaders produce extraordinarily positive results in organizations—and can help you produce positive results in yours.