Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The next step in your DEI journey starts here. Building on the knowledge base of DEI Deconstructed, Lily Zheng offers a workbook with 40 original exercises, worksheets, and other tools to help guide you and your organization toward more substantive and lasting DEI outcomes. Whether you're a new or veteran DEI practitioner looking to improve your practice, a leader looking to grow your leadership skills, or an advocate looking to play more powerful roles in movements, this book will give you the practical tools to do just that.

From self-work to organizational change, this workbook will upskill you with the core competencies required for impactful DEI work, such as diagnosing inequity, working with constituents, building movements, creating psychological safety, stewarding inclusive cultures, resolving conflict and harm, and achieving systems change. Most importantly, it will give you valuable experience putting these skills into action. Each activity can stand on its own and is designed to stimulate valuable reflection and practice. Included are recommendations for targeted exercise roadmaps to supplement your learning journey. Taken all together, these exercises are a complete masterclass in any practitioner's DEI education.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

The next step in your DEI journey starts here. Building on the knowledge base of DEI Deconstructed, Lily Zheng offers a workbook with 40 original exercises, worksheets, and other tools to help guide you and your organization toward more substantive and lasting DEI outcomes. Whether you're a new or veteran DEI practitioner looking to improve your practice, a leader looking to grow your leadership skills, or an advocate looking to play more powerful roles in movements, this book will give you the practical tools to do just that.

From self-work to organizational change, this workbook will upskill you with the core competencies required for impactful DEI work, such as diagnosing inequity, working with constituents, building movements, creating psychological safety, stewarding inclusive cultures, resolving conflict and harm, and achieving systems change. Most importantly, it will give you valuable experience putting these skills into action. Each activity can stand on its own and is designed to stimulate valuable reflection and practice. Included are recommendations for targeted exercise roadmaps to supplement your learning journey. Taken all together, these exercises are a complete masterclass in any practitioner's DEI education.

Those of us seeking to become or improve as DEI practitioners, inclusive leaders, and effective advocates may feel tempted to jump straight into a list of best practices. But creating the impact we seek requires more than just doing the right things, but also being right with ourselves—because skipping this step can result in avoidable harm to ourselves and those we’re working to benefit.

“WORKING FROM A PLACE OF KNOWING WHO WE ARE AND WHERE WE COME FROM IS, IN MY EXPERIENCE, ONE OF THE MOST POWERFUL WAYS TO GROUND OUR EFFORTS.

I’ve seen practitioners inflict moral injury1 and burnout on themselves, by only realizing that the work they’ve chosen to do compromises their value system after agreeing to take it on; make beginner’s missteps that compromise their impact, due to not unpacking their own privilege or positionality before engaging with marginalized communities; and even cause damage to organizations by acting out of unhealed trauma, rather than centering the communities they’re working on behalf of.

Self-awareness and understanding help protect against this. They help us as practitioners push back against work that compromises our values, know our lane when it comes to complex issues of identity, and pursue our own healing outside of our work so we can work more sustainably and healthily.

Building self-awareness can also help us discover and rediscover our own power and expertise. Working from a place of knowing who we are and where we come from is, in my experience, one of the most powerful ways to ground our efforts. It’s a fitting foundation for the work we’ll be doing together in this book.

1 Establish Your Values

Personal values are the guiding priorities in our lives that together make up our moral code and sense of self. The values that are most important to us are those that, if our thoughts and actions align with them, make us feel a sense of purpose and fulfillment, and if our thoughts and actions are unaligned with them, make us feel a sense of directionlessness, dissatisfaction, and even distress.

For DEI practitioners, values can feel like a pretty granular place to start. But look more closely at the choices that practitioners make, and you’ll find that values are often at their heart. Many of us leave jobs because we’re asked to compromise our values at work. Many of us choose the employers, industries, and even the careers we do because we’re looking to follow our core values. The scary thing? While many of our values stay consistent, our values can and often do change throughout our lives.2 Being able to name and recognize our values—especially if they’ve changed since we’ve last thought explicitly about them—helps us track what matters most to us, guide the choices we make every day, and remind us who we are no matter what situations we find ourselves in.

PRACTITIONER’S TIP

One of the underappreciated benefits of exploring your values is that it can increase your receptiveness to new, and potentially challenging, information. Even the simple task of quickly jotting down a list of your values, an exercise called a “values affirmation,” has been shown to increase our ability to take constructive criticism and resist defensiveness.3 Consider revisiting this exercise whenever you’re about to go into a tough situation, to get a quick dose of fortitude.

LEARNING GOALS

■ Identify your eight core values, and explore how they might show up (or not) in your life.

■ Be able to fluently articulate your own values, and connect them to your day-to-day behaviors.

■ Reflect on and document how your values may have evolved or changed over time.

INSTRUCTIONS

Read the following list of 60 common values. Out of all of them, circle or mark the eight core values that you think best define who you are. List them in any order in the My Eight Core Values chart, and for each, share some thoughts on how this value shows up in your life in your thoughts and behaviors. Afterwards, answer the reflection questions.

|

Acceptance To be welcomed as I am |

Accuracy To be correct and precise in my opinions and actions |

Achievement To accomplish valuable goals |

Adventure To have new and exciting experiences |

|

Attractiveness To feel and be seen as physically attractive |

Authenticity To behave in a manner that is true to who I am |

Authority To be in charge of others |

Autonomy To be independent and self-determining |

|

Beauty To appreciate and be surrounded by beautiful things |

Comfort To have a pleasant, enjoyable life |

Compassion To feel and show concern for others |

Contribution To meaningfully benefit or add to society |

|

Courage To be strong and take action in the face of fear, pain, or grief |

Creativity To have new and original ideas and create new things |

Dependability To be reliable and trustworthy |

Duty To carry out my responsibility to people and society |

|

Ecology To live in harmony with and protect the environment |

Faith To have a strong belief in God or the doctrines of religion |

Fame To be known and recognized |

Family To have a happy, loving family |

|

Flexibility To adjust to new or changing situations easily |

Forgiveness To be compassionate to those who have harmed me or others |

Friendship To have close, supportive friendship and companionship |

Fun To have experiences of play, amusement, and enjoyment |

|

Generosity To give what I have to others |

Gratitude To readily show appreciation for and return kindness |

Growth To continually be changing |

Honesty To be truthful and genuine |

|

Humility To be modest and unassuming |

Humor To see the humorous side of myself and the world |

Industry To work hard and well at my life tasks |

Integrity To live consistently by a set of personal principles |

|

Intimacy To share my innermost experience with others |

Justice To promote equal and fair treatment for all |

Knowledge To learn and possess valuable knowledge |

Logic To live rationally and sensibly |

|

Love To give love to others and be loved |

Loyalty To provide strong support for a long period |

Mastery To attain a high level of competence in my chosen activities |

Moderation To avoid excess and find a middle ground |

|

Orderliness To have a life that is well organized |

Peace To seek personal peace and peace in the world |

Pleasure To seek and have experiences that feel good |

Popularity To be well-liked by many people |

|

Power To have influence or control over the outcomes I desire |

Purpose To have meaning and direction in life |

Responsibility To make and carry out important decisions |

Safety To be physically safe and secure |

|

Self-Control To be disciplined and govern my own activities |

Self-Esteem To feel positive about myself |

Self-Knowledge To have a deep understanding of myself |

Service To be of service to others |

|

Sexuality To have fulfilling sexual relationships with others |

Simplicity To live life simply and minimally |

Spirituality To seek and find connection to something bigger than myself |

Stability To have a life that stays consistent |

|

Strength To be physically and emotionally strong and enduring |

Tolerance To accept and respect those different from me |

Uniqueness To be seen as remarkable, special, or unusual |

Wealth To have plenty of money |

MY EIGHT CORE VALUES |

THIS VALUE SHOWS UP IN MY LIFE WHEN I |

1. |

|

2. |

|

3. |

|

4. |

|

5. |

|

6. |

|

7. |

|

8. |

|

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

1. How have your values influenced your life decisions? Think about your friends and family, career, education, intimate relationships, and any other important decisions you may have made.

2. How have your values changed over time, and why did they change? How easy or hard was it to notice when your values had changed?

3a. Name an action you took in the last week that embodied one or more of your current core values. How did you feel after taking it, and why?

3b. For the action you named, what circumstances made it easier to practice your values?

4a. Name an action you took in the last week that contradicted some of your values. How did you feel after taking it, and why?

4b. For the action you named, what circumstances made it harder to practice your values?

5. Given these reflections, what changes can you make in your habits and behaviors to better embody or practice your core eight values going forward?

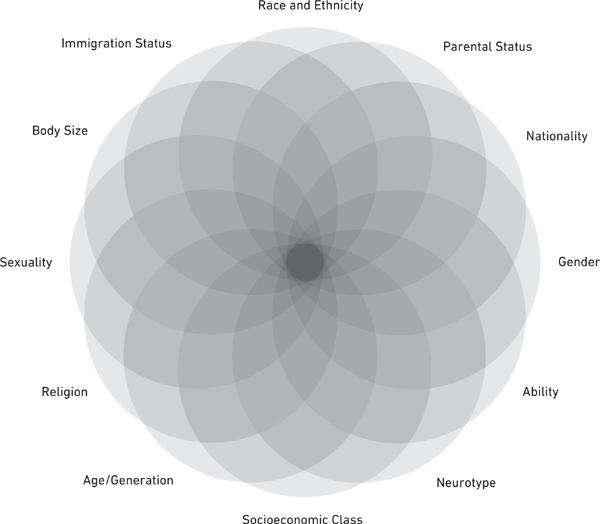

2 Claim Identity

Everyone has a relationship to social identities: race, gender, age/generation, ability, sexuality, class, religion, nationality, and much more. These identities do more than just connect us with other similar people; they also impact our experiences in the world, whether or not we’re aware of it. Some identities are marginalized—associated with typically more negative experiences. Other identities are privileged—associated with typically more positive experiences.

Our identities don’t exist separate from each other, or in a vacuum. We often experience multiple identities simultaneously, and we can be treated differently on the basis of multiple identities at once. For example, Black women don’t just have the experiences of being Black added to the experiences of being a woman, but have unique experiences at the intersection of Blackness and womanhood deserving of deeper analysis. This is the concept of intersectionality, an analytic perspective developed by race scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw that lets us examine the various interlocking parts of our identities simultaneously.4 Because our unique combination of identities strongly influences how we navigate and experience the world, the more we can analyze the role our many identities play in concert with each other, the better we can understand the world around us and our place within it.

PRACTITIONER’S TIP

A common experience is finding it much harder to reflect on privileged identities, compared to marginalized ones. Feeling some amount of emotion or resistance is normal! You may think at some point, “I don’t have privileges; I had to work hard to earn what I have.” Recognize that this exercise isn’t about your effort or hard work, but instead about documenting the headwinds and tailwinds in our lives making things harder or easier for us, respectively. Use this exercise when you’re looking to zoom out a bit from your day-to-day for a different perspective on your own experiences, challenges, and successes.

LEARNING GOALS

■ Name your own identities across some of the most common identity dimensions, and identify which are relatively privileged vs. relatively marginalized.

■ Connect your understanding of your identity intersections to your unique life experiences.

■ Build fluency with using privilege and marginalization as tools to analyze your day-to-day.

INSTRUCTIONS

Review the intersectionality graphic,5 and fill in the chart with your own identities. A list of example identities is included if you need inspiration. Once you’ve finished, answer the reflection questions.

“Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides. Where it locks and intersects. It is the acknowledgment that everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and privilege.” —KIMBERLÉ CRENSHAW

TYPE OF IDENTITY |

DEFINITION |

EXAMPLES |

YOUR IDENTITIES |

Race and ethnicity |

Social groupings related to shared physical and cultural traits |

Black, White, Asian, Indigenous, Latine, Yoruba, Arab, Han Chinese, Romani |

|

Parental status |

Whether you have or parent a child or children |

Partnered vs. single parent, adoptive parent, guardian, nonparent |

|

Nationality |

The nation you belong to or originate from |

Guatemalan, Chinese, Thai, Pakistani, British, Samoan, Italian, Kenyan, American |

|

Gender |

Your innate sense of your gender and what it means to you |

Cisgender man, cisgender woman, transgender man, transgender woman, nonbinary, genderqueer |

|

Ability |

Your cognitive, social-emotional, and physical ability to perform tasks and navigate the world |

Nondisabled, deaf/hard of hearing, vision impaired, chronic pain, learning disability, physical disability |

|

Neurotype |

The way you think, learn, and communicate compared to “normal” |

Neurotypical, neurodivergent, autistic, ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia |

|

Socioeconomic class |

Social grouping related to economic status |

Upper, upper-middle, middle, working, lower |

|

Age/generation |

The length of time you have lived or your generational cohort |

(In the US) baby boomer, Gen X, millennial, Gen Z, Gen Alpha |

|

Religion |

Your system of faith, belief, and worship |

Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, nonreligious |

|

Sexuality |

Your relationship to intimate attraction and expression |

Heterosexual, gay, bisexual, queer, asexual, pansexual |

|

Body size |

Social grouping related to your physical traits |

Tall, short, fat, skinny, larger-bodied |

|

Immigration status |

Related to your immigration generation |

First-, second-, or third-generation; nonimmigrant |

|

Another identity important to you |

Name a social identity not on this list important to your self-definition! |

Veteran status, region, education, occupation, first language, etc. |

|

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

1. Of the 13 dimensions of identity shown on the graphic and in the chart, some may on average confer you advantages or disadvantages in your society or organization. Which of your identities are relatively marginalized? Which are relatively privileged?

Marginalized Identities

Privileged Identities

2. Thinking about your marginalized identities, how have they impacted your life experiences overall? What are some unique barriers you might have faced due to these identities?

3. Thinking about your privileged identities, how have they impacted your life experiences overall? What are some unique advantages you might have faced due to these identities?

4. Pick two of your marginalized identities, if applicable. How might these identities have both simultaneously contributed to a unique barrier or disadvantage you faced?

5. Pick two of your privileged identities, if applicable. How might these identities have both simultaneously contributed to a unique advantage you experienced?

6. Think about your work (including non-DEI-related work). How do your identities impact how you perceive your work and are perceived by others while working?

3 Center Your Expertise

Our combination of identities gives us a unique perspective on the world; going further, by dint of these identities, we can even think of ourselves as experts when it comes to certain topics. Your unique mix of identities as a disabled, transgender person who menstruates, for example, might make you an expert on aspects of the US medical system due to how many times you’ve engaged with it. Your unique mix of identities as an upper-middle class White man with an Ivy League education, for example, might make you an expert on navigating predominantly White workplace environments due to your experience in similar contexts.

Our identities by definition make us experts—but because our identities are unique, so too is our expertise limited. Understanding the gaps in our knowledge and experience helps us practice humility and curiosity, and effectively seek out the expertise of those with other experiences to gain a more complete understanding of our society.

PRACTITIONER’S TIP

Expertise can be a double-edged sword, especially if it’s related to identity. The biggest risk is a cognitive bias called the “curse of knowledge” or the “curse of expertise”: the assumption that other people have the same background knowledge to understand things that seem obvious to us as experts.6 As a result of this bias, identity-related conversations can end in frustration when we realize the hard way that what feels like the most basic or obvious of observations to some (“this process is racist!” or “utilizing this resource is easy!”) may feel incomprehensible to others. This exercise is about slowing down and practicing articulating not only your own expertise but also your personal gaps in knowledge. Revisit it when you’re preparing for a conversation about identity with someone very different from you.

LEARNING GOALS

■ Connect your most salient social identities to discrete topics of expertise and experience.

■ Acknowledge gaps in your expertise related to identities you do not possess.

■ Practice communicating identity-related expertise by drawing on life experience.

INSTRUCTIONS

Answer the exercise questions to outline and reflect on your own identity-related expertise. If you’re looking for a challenge at the end of the exercise, draw on your answers to develop a short lecture or presentation on your expertise to deliver to a friend or colleague.

1. List up to four social identities that you would say collectively have the largest bearing on your everyday experiences. For examples of social identity, refer to Exercise 2: Claim Identity. For each, circle whether the identity is relatively privileged, relatively marginalized, or neither—for example: upper-middle class (privileged), queer and transgender (marginalized), neurodivergent/autistic (marginalized), DEI consultant (neither).

1. |

Privileged |

Marginalized |

Neither |

2. |

Privileged |

Marginalized |

Neither |

3. |

Privileged |

Marginalized |

Neither |

4. |

Privileged |

Marginalized |

Neither |

2. For each identity you listed, list at least one environment or community that you are more comfortable navigating and one that you are less comfortable navigating due to your identity—for example: nice restaurants, rural environments; online queer and trans communities, traditional weddings; niche interest communities, extended social gatherings; corporate workplaces, employee-organized communities, unions.

COMFORTABLE |

LESS COMFORTABLE |

1. |

1. |

2. |

2. |

3. |

3. |

4. |

4. |

3. For each identity you listed, list at least one topic that you have more expertise about and one topic that you have less expertise about due to having that identity (and not others)—for example: graduate school systems, unemployment and SNAP program; history of queer and trans movements, traditional heterosexual dating; double empathy problem, implied communication norms; DEI in the workplace, long-term workplace politics.

MORE EXPERTISE |

LESS EXPERTISE |

1. |

1. |

2. |

2. |

3. |

3. |

4. |

4. |

4. Drawing from your answers to questions 1-3, if you had to give a 10-minute presentation on a topic you have identity-related expertise with, what would you choose?

5. Try to put yourself in the shoes of someone very different from you hearing your presentation. What aspects of your presentation would be most novel to those without your identity?

6. Think of the same topic but presented by someone with entirely different identities from you, with different privileges and different marginalizations. How do you imagine their presentation might differ? Why?

7. If you could request a 10-minute presentation from another person on a topic you lack identity-related expertise with, what would you choose?

8. What aspects of that presentation would you be hoping to learn more about; what would be most novel or interesting to you?

9. Finally, think about your own organization or community. If you were to sum up your identity-related expertise related to that organization, how would you describe it?

10. If you were to sum up the gaps in your identity-related expertise related to that organization or community, how would you describe them?

BONUS EXERCISE: PRESENT YOUR EXPERTISE

Plan out and actually deliver a 10-minute presentation on your identity-related expertise for a friend or colleague interested in hearing it, building on your previous answers to questions 1-10. Then, reflect on the following questions:

■ What did you feel more or less comfortable with during your presentation?

■ How was it received? To what extent did your audience learn something new?

■ How might you improve that presentation if you were to deliver it again?

4 Unpack Your Experiences

All of us have experienced hardship throughout our lives. Whether intense one-time events; repeated harm lasting weeks, months, or years; or even experiences of discrimination, violence, or oppression occurring over generations, hardship often sticks with us in some form or another. For many of us, especially those with one or more marginalized social identities, that hardship has had a significant bearing on the person we are today. These experiences aren’t good or bad—they simply are. Yet, how we internalize and respond to these experiences has bearing on our efficacy as DEI practitioners.

On the one extreme, living in a constant state of emotional activation tied to our hardship or trauma can be dangerous.7 We may inadvertently prioritize unmet needs in ourselves, rather than centering the communities and organizations we are working to benefit, and as a result do harm. On the other extreme, trying to act like the hardship we experienced never happened can be equally harmful. Repressing our triggers and working without attending to ourselves can result in long-term burnout, compassion fatigue, and diminished impact.8 Naming our experiences—even traumatic ones—without judgment and tying them to who we are today can help us start unpacking what we’re each bringing to the DEI work we do.

PRACTITIONER’S TIP

This exercise is a deeply personal self-examination. Utilize it when you’re looking for insight into or a reminder of your own life experiences below the surface, and as part of a process of recalibrating your overall reason and approach to DEI work.

Reflecting on hardship, especially traumatic experiences, can be a taxing experience for anybody. Ensure that you feel physically and mentally prepared for potentially difficult emotions to surface during the exercise before beginning, and give yourself permission to pause or skip the activity if you’re feeling overwhelmed. During the exercise, if you find yourself needing to relax, consider utilizing deep breathing or paired muscle relaxation (tightening, then relaxing them), engaging in physical movement, splashing your face with cold water, or otherwise utilizing what are called “distress tolerance skills.”9 If you’re finding that this exercise is bringing up more intense emotions than you can tolerate, consider reaching out to a mental health professional to continue processing these experiences with more formal support and guidance.

LEARNING GOALS

■ Name and reflect on your experiences of hardship and trauma.

■ Reflect on how your hardship and trauma affect your thoughts and behaviors, and list your present-day triggers.

■ Describe how greater awareness of hardship and trauma might benefit your DEI work.

INSTRUCTIONS

The following chart lists different types of hardship and trauma by category: acute, chronic, complex, and historical. Fill out the chart with examples of your own experiences of hardship or trauma, if any, then answer the reflection questions. Remember to stay in touch with your emotions as you fill this chart out, taking breaks as needed. It’s okay if you choose not to write down all of your experiences, and also okay if you don’t have any experiences of hardship or trauma in one or more categories.

CATEGORY |

DEFINITION |

EXAMPLES |

YOUR EXPERIENCES |

Acute |

A single, isolated incident |

■ Natural disasters ■ Single acts of violence or terrorism ■ Sudden unexpected losses (of loved ones, relationships, possessions, ability, etc.) |

|

Chronic |

Experiences that are repeated and prolonged |

■ Prolonged family or community violence ■ Long-term illness ■ Chronic bullying ■ Chronic poverty ■ Repeated discrimination ■ Repeated exposure to loss and grief |

|

Complex |

Traumatic experiences, often at an early age, involving the feeling of powerlessness |

■ Physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse ■ Neglect or abandonment ■ Witnessing domestic violence ■ Human trafficking ■ Living in a war zone |

|

Historical |

Collective experiences shared by a cultural group across generations |

■ Generational trauma from war, displacement, and violence ■ Systemic racism ■ Colonization/imperialism ■ Genocide/ethnic cleansing |

|

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

1. What was the hardest part of this exercise for you? What emotions came up, if any?

2. In what ways have your acute experiences of hardship or trauma shaped who you are today? Consider your behaviors, habits, preferences, lifestyle, and relationships. You can skip this question if you did not list any acute experiences.

3. In what ways have your chronic experiences of hardship or trauma shaped who you are today? You can skip this question if you did not list any chronic experiences.

4. In what ways have your complex experiences of hardship or trauma shaped who you are today? You can skip this question if you did not list any complex experiences.

5. In what ways have your historical experiences of hardship or trauma shaped who you are today? You can skip this question if you did not list any historical experiences.

6. How do your experiences shape your approach to work, especially DEI-related work? What new insights or thoughts emerge after making these connections?

7. What triggers—things that cause painful memories or emotions to surface—might you have related to your experiences? How do you or might you manage these triggers in your work?

8. How might unpacking personal experiences of hardship and trauma be useful for your own DEI work? List potential benefits of doing so, and potential risks to be managed.

“NAMING OUR EXPERIENCES—EVEN TRAUMATIC ONES—WITHOUT JUDGMENT AND TYING THEM TO WHO WE ARE TODAY CAN HELP US START UNPACKING WHAT WE’RE EACH BRINGING TO THE DEI WORK WE DO.

NOTES

1. The Moral Injury Project. “What Is Moral Injury.” What Is Moral Injury, July 5, 2017. https://moralinjuryproject.syr.edu/about-moral-injury.

2. Foad, Colin M. G., Gregory G. R. Maio, and Paul H. P. Hanel. “Perceptions of values over time and why they matter.” Journal of Personality 89, no. 4 (2021): 689–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12608.

3. Crocker, Jennifer, Yu Niiya, and Dominik Mischkowski. “Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive other-directed feelings.” Psychological Science 19, no. 7 (2008): 740–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02150.x.

4. National Association of Independent Schools. “Kimberlé Crenshaw: What Is Intersectionality?” YouTube, June 22, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc.

5. “Intersectionality.” Instagram. August 9, 2020. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDrJDbHBdaw/.

6. “Curse of Knowledge.” The Decision Lab, July 17, 2021. https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/management/curse-of-knowledge.

7. Chin, Dorothy, Amber M. Smith-Clapham, and Gail E. Wyatt. “Race-based trauma and post-traumatic growth through identity transformation.” Frontiers in Psychology 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1031602.

8. Newell, Jason M., and Gordon A. MacNeil. “Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue.” Best Practices in Mental Health 6, no. 2 (2010): 57–68.

9. Compitus, Katherine. “What Are Distress Tolerance Skills? The Ultimate DBT Toolkit.” PositivePsychology.com, March 3, 2023. https://positivepsychology.com/distress-tolerance-skills/.