Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Be a Project Motivator

Unlock the Secrets of Strengths-Based Project Management

Ruth Pearce (Author)

Publication date: 11/27/2018

—John Garahan, Vice President, Global Delivery, Broadridge Financial Solutions

Successful project managers must engage and motivate others to achieve complex goals. Ruth Pearce shows how behavior, language, and attitudes affect engagement and how leveraging character strengths can help improve relationships, increase innovation, and build higher-functioning teams. This focus on character strengths—such as bravery, curiosity, fairness, gratitude, and humor—can help project managers recognize and cultivate the things that are best in themselves and others.

Many project managers do not have the authority to direct the activities of people on their teams—they can only influence them. The most influential people succeed by focusing less on themselves and their message and more on others. They pay attention, they are brave, they are vulnerable, they are curious, and they look for and acknowledge the things that are important about and to the other person. And they model the behavior that they want to see. This book tells you how.

Pearce provides tools and frameworks for building a culture of appreciation, understanding character strengths, mapping leadership qualities, understanding learning styles, identifying team roles, and executing plans. She also explores the factors that contribute to conflict and tensions, as well as strategies for getting through difficult times. We see these tools and techniques in action through “Maggie,” a project manager who is struggling to motivate her team. Each chapter concludes with reflective questions to make the ideas stick and with key strategies for success.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

—John Garahan, Vice President, Global Delivery, Broadridge Financial Solutions

Successful project managers must engage and motivate others to achieve complex goals. Ruth Pearce shows how behavior, language, and attitudes affect engagement and how leveraging character strengths can help improve relationships, increase innovation, and build higher-functioning teams. This focus on character strengths—such as bravery, curiosity, fairness, gratitude, and humor—can help project managers recognize and cultivate the things that are best in themselves and others.

Many project managers do not have the authority to direct the activities of people on their teams—they can only influence them. The most influential people succeed by focusing less on themselves and their message and more on others. They pay attention, they are brave, they are vulnerable, they are curious, and they look for and acknowledge the things that are important about and to the other person. And they model the behavior that they want to see. This book tells you how.

Pearce provides tools and frameworks for building a culture of appreciation, understanding character strengths, mapping leadership qualities, understanding learning styles, identifying team roles, and executing plans. She also explores the factors that contribute to conflict and tensions, as well as strategies for getting through difficult times. We see these tools and techniques in action through “Maggie,” a project manager who is struggling to motivate her team. Each chapter concludes with reflective questions to make the ideas stick and with key strategies for success.

For twenty years Ruth Pearce has worked in the financial services sector project managing complex programs and large teams. Most recently she has been using evidence based positive psychology techniques to build resilient, high performing teams as well as creating and delivering workshops focused on increasing wellbeing for teenagers. As a project manager, she believes that we need to not just ORGANIZE, but also need to ENERGIZE. We need to be agents of ENGAGEMENT and not just agents of change.

1

Project Managers: More Than Just Plate Spinners and Ball Jugglers

Project managers can be a big reason for a project’s success and a big reason for its failure. It is our choice which we are.

Most of this book is about doing things better. It focuses on building skills, increasing your influence, and making things better for you and those around you. This chapter makes the case for why all these things are important. There are quite a few statistics. Some of them focus on the world at large and are from organizations such as the Project Management Institute (PMI), Gallup, and the VIA Institute on Character. But a big part of this chapter is about you. I asked project managers and their stakeholders what the role of the project manager is. I asked project managers what they have to do with team engagement, how much they know about it, and how much they want to know. And finally, I asked project managers about their strengths—or superpowers—and also about their potential challenges.

Things to Look Out For

1. Learn how we and our stakeholders view project managers.

2. Understand how fellow project managers perceive engagement and their role and readiness.

3. Appreciate why engagement is important in motivating teams.

4. Find out what strengths project managers already have—and where they need help.

Implementing the Platinum Rule—Treating People as They Want to Be Treated

Social intelligence and emotional intelligence are very popular concepts in the workplace these days, and as project managers, we need to use social intelligence at every turn if we are going to be successful.

I, like many of you, was brought up using the Golden Rule to deal with others: treat others as you would want to be treated yourself. This did not seem like such a bad rule until I reached high school and started to mix with people who had very different backgrounds from mine. At that point, I started to realize that many people did not have the same values that I did and did not want the same life I did. As someone who, even then, was incurably curious and had a passion for learning—although not always for school—my values and behaviors were not the same as those of people who valued relationship building, or who focused on their family or church community, or who loved arts and creativity. It was not necessarily in either of our best interests to treat them as I would like to be treated.

Years later, I came across the Platinum Rule, which says that we should treat others as they would like to be treated. This seems rational and reasonable, a laudable goal, except then we are pretty much left on our own to fathom how people want to be treated. Of course, we can always ask, but that is not always practical when we are dealing with dozens or hundreds of people a day in the workplace or we are communicating in an impersonal medium such as email or text.

At the heart of this book is a series of practices that help us to answer the question, How do other people want to be treated? Answering that question will help you build social intelligence and will allow you to develop a greater sense of connection with, and kindness and even love toward, your teams.

In this book, I will share some of the things I have learned and am continuing to learn. My goal is to share with you some empowering and useful tools that have taken me years to discover. They are all simple, effective, and fun. Even if you can only experience and practice them yourself, you will see a benefit—and so will those around you. If you are feeling brave, you can share all the methods from the book with others. And if you are feeling very brave, or you happen to work in a very open, accessible work environment, you can even suggest to your leadership team that these tools and practices be shared more broadly.

With this book you can start to implement the Platinum Rule—and start to treat people the way they want to be treated!

When we see people for who they are, and treat them as they want to be treated, they become engaged. When they are engaged, they are motivated. And when they are motivated, they get stuff done.

Why Do Project Managers Need Their Own Book on Engagement?

Regardless of the audience, the basic foundations we need to build engaged, connected, and empowered teams are the same. When we use curiosity to prospect for and leverage strengths, embody bravery through vulnerability, and model the behavior we want to see, teams flourish.

This may sound hard to do—especially embodying bravery!—but these components integrate naturally and are straight-forward to learn and apply. Your skill and comfort level with these concepts will grow over time, but even a little bit of each will make a big difference in your day-to-day experience.

Of course, there are many books out there about engagement, and lots of research that shows the amazing things that can happen when people are engaged. Why do we need a book specifically for project managers?

First, I think project managers are only just starting to understand the importance of engagement in their own success. A book specifically targeted at project managers accelerates the learning and understanding.

Second, as a project manager myself, I often find it hard to apply the information provided in books about engagement because they usually start from an assumption of power and control—that is to say, authority.

It appears to be much easier for a line manager who does appraisals, conducts performance reviews, and sets bonuses to implement tools and techniques to foster engagement than it is for people who have no such formal influence. Indeed, as in my own case, we are often contractors with no formal standing in the organizational structure. Many of these books have nearly lost me at the introduction because they ask me to work toward a three-day off-site team-building event or they talk about how particular assessments and tools are “inexpensive.” Of course, there are still things to be gleaned from these books, but it takes time and energy—both of which are in short supply in our field! This book is focused on your world and makes no assumption about how much authority you enjoy. It is written for you.

Finally, the sheer volume of management, team engagement, positive psychology, and organizational psychology books is overwhelming. I have spent years reading, studying, and trying out techniques from books, research papers, classes, and conferences to see what works, what people buy into, and what is nice in theory but not very practical in real project management life. I have no doubt that there are other practices that are beneficial. But the techniques I describe in this book are what have worked for me. They are tested and proven!

Collecting Evidence: What Project Managers Contribute

Over the last two years, I have asked lots of people lots of questions about project managers. The first question was, “What do we expect of a project manager?”1

To find out the answer, I surveyed 266 people—half of them were project managers, and the other half were people who work with project managers.

Overall, there were three major takeaways:

1. Expectations of project managers are high. Of the respondents, 85 percent agreed with the statement, “Project managers are essential to project success.” We believe that project managers are drivers of that success, providing context and purpose, making things happen, and ensuring that team members know who is doing what and when. We assign a great deal of responsibility to project managers.

2. Project managers see themselves more as holders of the big picture, keeping their eye on the goal of the project. Of the project managers I surveyed, 75 percent said they believe they have a good sense of the big picture.

3. I discovered that project managers believe that the biggest disadvantages of having a project manager are micromanagement, bureaucracy, and too many meetings. Yes, even project managers think these are our limitations!

4. Most project managers see themselves as “drivers” of the project.

Drive Matters, but What Does It Mean?

Driving is hard work. Force takes energy. It can be distressing and depressing, and it often results in pushback and resistance.

At its most negative, drive implies inescapable force, relentless urging, or coercion into an activity or following a direction. It often implies physical force—such as driving a golf ball or driving a nail into a beam. Overall, though, drive implies keeping things in motion.

Is that really what we want to do as project managers? Force team members to perform? Act relentlessly in pursuit of the project goal? Or do we want to activate, inspire, and engage team members in the goal?

Building engagement to motivate people to get the work done is much more gratifying, leads to better relationships, and results in increased personal, team, and organizational satisfaction. Leading from within, and experiencing people moving along with you, is much less exhausting than pushing from behind.

In answer to the statement, “The worst thing about having a project manager is . . . ,” the most common responses were that project managers

micromanage the resources and tasks;

are too structured and rigid;

are too task oriented;

hold too many meetings with the wrong people in the room;

have too little knowledge about the specifics of the program; and

have too little skill as a project manager or are too junior for the project at hand.

It seems that we look to project managers to provide context and purpose, understand the big picture, and keep things on track (as opposed to just tracking things!). They are expected to look beyond the individual tasks to the whole and to make things happen.

But if project managers are widely believed to be essential to success, and research shows that engagement is essential to success,2 doesn’t it follow that project managers need to focus on engagement? Are project managers engaged? Do they know—or want to know—how to engage others?

Collecting Evidence: What Others Think about Project Managers

With that same project manager effect survey, I was able to ask the same number of non–project managers what they think.

From this group, there were three major takeaways:

1. Non–project managers agree that project managers are drivers of success, providing context and purpose, making things happen, and ensuring that team members know who is doing what and when. This group also attributed a great deal of responsibility to project managers.

2. Expectations differ when it comes to the project manager’s understanding of the big picture versus his or her focus on the underlying tasks. Whereas project managers see themselves as focused on the big picture, non–project managers see them as more focused on tasks, sometimes to the detriment of the overall project or program.

3. Like project managers, other respondents reported that the biggest disadvantages of having a project manager are micromanagement, bureaucracy, and too many meetings.

Expectations are high, and this raises the question of how many of us are ready to live up to those expectations. As a young project manager, I certainly was unaware of these expectations, and had I known what they were, I would have been ill equipped to meet them. Had I gone looking, I would have been challenged to find resources to help me.

It is good to know that in response to the statement, “Project managers are essential to project success,” there was remarkable agreement. The difference between project managers and non–project managers was the degree to which they agreed with the statement. Project managers feel more strongly that they are needed for a project to succeed.

Where expectations do not match, we must consider both the actual performance of project managers in the role and the communication that occurs between project managers and their team members. If project managers have a clear understanding of the big picture, for example—and 75 percent of project managers seem to think they do—how is it that only just over 50 percent of non–project managers believe this is the case?

Seeing the big picture and being the single point of contact were considered critical success factors by respondents, but respondents’ concern that project managers can get in the way, possibly hindering progress, is worrying. It presents another opportunity to make things better.

This issue is highlighted in the responses to the statement, “The worst thing about having a project manager is . . . ,” with many respondents citing micromanagement, bureaucracy, too many meetings, and too much structure or rigidity as obstacles to project success. A disappointing half of respondents in both groups seemed to believe that project managers slow down development with too many meetings, which is an indication that project managers may be perceived as brakes and not accelerators on a project.

It is most worrying, to me at least, that project managers seem to share that view.

Collecting Evidence: What Others Say about Project Managers

Looking at some of the comments provided by respondents, we see some interesting feedback.

Common responses to the statement, “The best thing about a project manager is . . . ,” included the following:

Accountability—both having one person who is accountable (the project manager) and having that person make sure that others are held accountable for their part in the project.

Communication—with stakeholders, team members, management, vendors, and other partners. PMI identifies communication as 90 percent of an effective project manager’s function.3

Organization, planning, coordination, and tracking—making sure that people hit deadlines, obstacles are removed, the right resources are available, and everyone has clear roles and responsibilities.

However, the two most prevalent answers were the following:

having a single point of contact for all concerned—the person to go to for information, escalation, clarification, and organization

having someone drive the project or program

What You Can Do to Put Your Projects in the “Successful” Category

Failed projects can give a project or program manager a bad rap, but there is more to project management success than project success. For example, a project manager colleague of mine, early in his career, was instrumental in getting a program canceled sooner rather than later, thus saving the organization hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. He had to summon up his courage to challenge the previous decisions and make the case for canceling the project.

And there are lots of projects that fail!

In the 2016 Pulse of the Profession Report,4 PMI reported that only about half of all projects were completed within budget, only about 60 percent met the original project objectives, and fewer than 50 percent of projects were completed on time. Losses were estimated at $122 million for every $1 billion spent. That is 12.2 percent of project budgets!

By 2017, the latest Pulse of the Profession Report5 showed that project success rates had improved year over year and that costs of failure had been reduced to $97 million per billion. Hopefully, this is the start of a trend, but project managers can help ensure that it is by building engagement, getting our teams behind our projects, and creating environments in which stakeholders are emboldened to speak up when things are going off course, needs have changed, or the project no longer makes sense.

In the 2013 Project Management Talent Gap Report,6 PMI forecast that between 2010 and 2020, 15.7 million project management jobs will be created worldwide, with 6.2 million of those in the United States. There will be more of us, and we will be involved in industries and projects that will shape the future. We will interact with a wider variety of team members, doing ever more novel tasks in ever more flexible, diverse, dispersed working environments. Relationship management, influence, and engagement will become more and more important if we, our teams, and our projects are to succeed.

Collecting Evidence: The Project Manager’s Perspective on Engagement

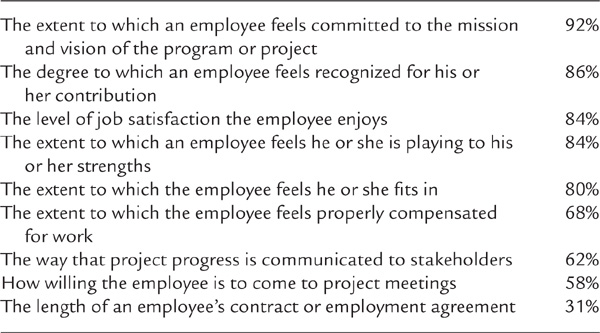

To understand how project managers as a group view engagement, I recently conducted an online survey of 138 of them.7 Among other questions, the group was asked to select one of nine responses to the prompt, “To me employee engagement means . . .” The answers and response frequencies are listed in Figure 1.1. (Note: Respondents could pick more than one answer.)

As you can see from the table, for this group of project managers, engagement includes ideas such as commitment and alignment to organizational goals, sense of recognition and fit, level of job satisfaction, and the extent to which employees feel they are playing to their strengths. To a lesser extent, engagement relates to compensation and to the way that stakeholders are updated about the project.

FIGURE 1.1 Project Managers’ Views on Engagement

Gallup tells us that engaged employees “work with passion and feel a profound connection to their company. They drive innovation and move the organization forward.”8 The organization may be the company, school, or any other enterprise we work for, and in my experience, engagement can also be created within the project team, often independent of the culture of the overall organization. I think that is worth repeating: we can build engagement and commitment within a team independent of the corporate culture. However, to do it, we often need to be brave.

The alignment of an employee’s values, goals, and aspirations with those of the team and the organization is a direct predictor of happiness, health, and productivity. The benefit to a team or organization is that engaged employees contribute discretionary effort. They make things happen. They are willing to run through walls for each other.

But why do we, as project managers, need to worry about engagement? Why should we seek to build engagement when we, too, need to be engaged and are part of that team? Isn’t that somebody else’s job?

1. As project managers, we need to make sure that things get done. After all, the project manager is the person responsible for accomplishing the project objectives.9

2. Research shows that engaged people are motivated to get things done. For example, Gallup reports that engaged employees are 12.5 percent more productive.10

3. Further, research shows that employee engagement remains low—according to Gallup, only 13 percent of people worldwide and about 30 percent in the United States are actively engaged.11 That means 87 percent of people worldwide (and 70 percent in the United States) are not “emotionally committed to the organization and its goals”! Imagine having surgery if only 13 percent of the surgical team is committed to your full recovery, or driving over a bridge that had been built by a construction team on which only 30 percent of the members were committed to building a safe, reliable structure.

4. And what if I were to tell you that you can contribute to your own sense of engagement and that through modeling—also known as the ripple effect—we can build the engagement of others around us? You don’t need to wait for somebody else to get this ball rolling. You can do it!

Engagement Is Just the Start

Of course, having an engaged team does not guarantee success. Sometimes surgeries are unsuccessful—the person on the table cannot be saved. Commitment is not enough when skills are lacking. But who is more likely to try to develop the right skills—someone who is clock-watching or complaining at the water cooler, or someone who is engaged and committed to the goals?

Getting the team on board can seem like an impossible task, and we may fall back on the notion that it is somebody else’s job—particularly when we do not have line management responsibility. It is easy to see our role as tracking tasks and progress, reporting and tracking against budgets, and seeking out the people with the right technical skills. It is just as easy to decide that engagement is not in our sphere of control, that it resides with management, the organization, or Human Resources—in other words, somebody else, somebody who should be engaging us.

Based on experience and evidence, I contend that we, the project managers, need to inspire our teams, help them realize their potential, and work on reaching ours. I believe we are in a unique position to do so because we lead an initiative, something defined and relatively time constrained, and precisely because we are outside the day-to-day line management framework, with its performance appraisals and career structure. We can plan not only the milestones, tasks, and communications, and how we manage risk and change, but also how we engage ourselves and our team members. We can plan how to integrate new individuals into the team and how to keep existing team members energized and connected to the program. We can plan how to alleviate stress. We can plan how to help team members value growth and be their best selves.

The beauty is that in the process, we can have more fun and be more successful as project and program managers.

As part of the same survey, I asked project managers more about engagement.

Nearly 90 percent of them agreed that employee engagement is part of their role.

While some believed that they were somewhat skilled in engaging the team, 70 percent wanted to feel more engaged themselves.

Over 80 percent would like to learn more about how to engage themselves and others.

Sadly, only 36 percent of respondents felt that project management training courses tell us what we need to know to engage team members successfully.

The Magic of Engagement

As Gallup says, engaged employees have passion, feel connection and create drive.12 In the 2013 State of the Global Workplace report, Gallup researchers report that worldwide only 13 percent of the workforce is engaged.

Worse than that, 24 percent are actively disengaged, which means they can be disruptive, may take more days away from the office, and are likely to negatively influence the opinions of those who are not engaged, which accounts for 63 percent of the workforce.13

Actively disengaged employees, to quote Gallup, “aren’t just unhappy at work; they’re busy acting out their unhappiness. Every day, these workers undermine what their engaged coworkers accomplish.”14 These measures vary between countries, but at an overall level, this means that actively disengaged employees outnumber engaged employees two to one.

In my experience, actively disengaged people ripple through teams. Their negativity, complaining, naysaying, and general gloom rub off and can bring down the mood—and productivity—of a whole team. When people are feeling disconnected and disengaged, they inadvertently start to infect others around them. Negativity sweeps through the team like a plague! I have seen hopeful, optimistic teams decimated in this way. As you will see later, this often has to do with strengths that are being under-valued and overused. What they are working on does not feel aligned with their values and inner motivation. Even our most negative people have strengths to bring to a team.

And when you see those statistics, they tell you something, right?

Your teams are probably having their share of disengagement. Disengaged employees work somewhere!

And what about you? Are you engaged?

The biggest influence on the level of engagement has been found to be managers—the people who drive and direct our work. In fact, managers—and we project managers are, among other things, managers—account for 70 percent of the variance in engagement experienced by employees.15 Managers who help employees to identify their strengths and to use them in the workplace are more successful. Managers who focus on cultivating employees’ strengths rather than dwelling on weaknesses have more engaged teams, with 67 percent of employees reporting high engagement when the manager focuses on strengths. Employees who understand and use character strengths at work are eighteen times more likely to be flourishing.16 Good managers are motivators. Unskilled managers are a drag on a team.

But the good news is that we can all learn to be better and to cultivate strengths in ourselves and in our teams. We can contribute to the improving trend in project outcomes.

Where Engagement Comes From: Introducing Character Strengths

Some of the earliest research in the field of positive psychology was into the concept of character strengths. Character strengths are universally recognized and cross-cultural, and they are at our cores. We all have multiple character strengths—some that we use all the time and that feel natural, easy, and energizing, and others that we use more selectively, based on our situation. For most of us, there are some character strengths that are not easy to engage and that take work. For example, most people struggle to engage self-regulation.

Research by Gallup and the nonprofit VIA Institute on Character has shown that character strengths are a fast way to engagement. People who know, understand, and apply their strengths are more engaged, more likely to see their work as a calling, and more likely to give discretionary effort. Those who work for managers who focus on employees’ strengths, and highlight and cultivate them, are not only more likely to be engaged but also less likely to leave.

There are many ways to explore character strengths, but one of the simplest and most accessible is the assessment that is offered by the VIA Institute on Character. Throughout the book, I reference this assessment because it is so readily available and accessible, but you could start with any of the strengths tools that are available.

But what strengths do project managers have? Is there a project manager recipe?

Project Manager Character Strengths

To explore the question of whether project managers share some strengths more than others, I asked over one hundred project managers to take a character strengths survey and share their results with me. Here I share the results of the survey. In later chapters, I will explore the implications of the results.

I discovered that honesty, fairness or kindness, curiosity, and love of learning are very common in project manager profiles. Humility, self-regulation, and spirituality typically show up at or near the bottom of the ranking. Teamwork and leadership are generally in the middle—readily available but not go-to strengths for most project managers. At first glance this seems to imply something about project managers and the character strengths that they are most likely to manifest. We might think that if we see such a combination of character strengths in an individual, we can expect that person to choose project management. It could even suggest that we should recommend project management as a career path to such individuals.

Strengths That Make Project Managers Special

But if we were to draw that conclusion, we would be wrong. When we compare project manager profiles with the average profile in the United States, for example—which has honesty, fairness, love of learning, and curiosity as top four strengths—we see that our project managers are pretty typical of the US population at large. Research confirms that these strengths are those that typically show up in the workplace. The same is true of the bottom strengths for project managers. Just as with our project managers, spirituality, self-regulation, and humility show up in the bottom five strengths for people in the United States, and with very few exceptions, this is consistent across the world for self-regulation and humility (modesty), and even for spirituality; only 25 percent of countries rank this strength higher than in the bottom five. At second glance, then, project managers don’t seem very different from the average person.

However, as I dug deeper, there did appear to be two super-strengths that show up higher in a project manager’s profile on average than they do in the population at large.17 At this stage of the research, I have not analyzed the strengths in terms of which ones the best project managers have; that is the subject of a future study. For now, we are only focused on which strengths tend to show up more—and less—in project managers than in the population at large.

Superpower 1: Hope

The first superpower is the character strength of hope. Hope is expecting the best in the future and working to achieve it, believing that the future is something that can be controlled.18 Hope—that is, expecting a positive outcome that can be controlled by the team—would seem to be an essential characteristic in a project team, and all the better if it can be instilled by the project manager.

Hope is not wishing or just being optimistic. It is an active strength—it is the combination of having a goal, seeing a path-way to achieve the goal, and taking action (also known as agency) to follow the path and make the goal happen.19

On average, very few countries (15 percent) rank hope higher than my sample of project managers did.20

Superpower 2: Love of Learning

The other strength that shows up as a superstrength is love of learning. Only 3 percent of countries rank love of learning higher than we project managers do! In my sample, project managers ranked love of learning third, which makes it a signature strength. By comparison, in the United States, love of learning is, on average, ranked twelfth.21 One thing to note is that although, on average, love of learning ranks very high for project managers, the scores for love of learning show much more variation between individual project managers than do the hope scores.22

Love of learning is “mastering new skills, topics, and bodies of knowledge, whether on one’s own or formally; obviously related to the strength of curiosity but goes beyond it to describe the tendency to add systematically to what one knows.”23 Is this a strength you recognize in yourself? Our love of learning helps us as a group to make transitions between projects and teams. It may well be that the best project managers have a level of insider knowledge (discussed in Chapter 3), but love of learning makes it possible to develop that insider knowledge.

Situational Strengths—or More Superpowers?

In the middle of the strengths spectrum, there are two more strengths that are ranked differently by project managers than by the general population.

Superpower 3: Prudence

The first of these is prudence, which project managers ranked seventeenth, compared to the United States, which ranks it twenty-second. While this may look like an insignificant ranking difference, only 8 percent of countries rank prudence higher than we project managers do on average! It appears that prudence may be a project manager superpower too. I cannot think of a better strength to counterbalance hope. Incorporating far-sighted planning, as well as short-term, goal-oriented planning, prudence implies caution and consideration.

Superpower 4: Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence

Another high-ranking strength for project managers is appreciation of beauty and excellence, which project managers ranked tenth. In the United States, appreciation is ranked fifteenth. Out of the seventy-five countries surveyed, only 24 percent ranked appreciation higher on average than our project managers did. What special value does appreciation have for project managers? As you will see in Chapter 4, it can help us to build team appreciation and recognition—both areas that project managers highlighted in their responses on engagement. In my experience, people with appreciation of beauty and excellence high in their character strengths profile are more comfortable calling out achievement and offering recognition to colleagues.

Strengths Opportunities for Project Managers

The final consideration is whether there are any strengths that we use less of than the population at large. The most significant outcome is that we rank social intelligence nineteenth, whereas in the United States social intelligence is ranked tenth on average. Worldwide, only 7 percent of countries rank social intelligence eighteenth or lower, and none rank it lower than nineteenth.

Opportunity 1: Social Intelligence (Applying the Platinum Rule)

The key concepts of social intelligence are social awareness—that is, what we sense about others—and social facility, which is what we do with that awareness. Social intelligence helps us interact effectively with others, understanding what motivates them and how they feel. Doesn’t this sound a lot like the Platinum Rule?

Having lower social intelligence than average may present challenges in some of the most critical aspects of project management—effective communication and team building. How do we communicate effectively and build a team if we are not sensitive to how team members feel and think?

In the book Alpha Project Managers,24 Andy Crowe identifies communication as a key differentiator in the best project managers, and yet even the best project managers are not as good as they think they are, according to the feedback of stakeholders. If project managers as a group were able to communicate more effectively, this would be a significant factor in improving project outcomes. Stakeholders would better understand the true state of the project, project managers and their teams would receive more helpful input and feedback, and problems would be identified and tackled earlier, when they are less costly to address.

Opportunity 2: Perspective

The other lower strength that may be significant is that project managers rank perspective fourteenth on average, compared to the US average of ninth.25 Only ten countries (13 percent) rank perspective—which includes having a sense of the big picture, a trait identified as important for project managers to have—lower than fourteenth.

The core elements of perspective are the following:

a high level of knowledge;

the capacity to give advice; and

the ability to recognize and weigh multiple factors before making a decision.

People with perspective are often described as seeing the big picture. In my survey of the project manager effect, seeing the big picture was one of the most often cited critical functions of a project manager.

If we are lower in perspective than those around us and the world at large, what does that mean? One challenge is that we may not be able to effectively fulfill the role of focusing on the big picture. We may overestimate the importance of small obstacles or get lost in the detail and forget to take a step back to evaluate where a project stands.

One of the goals of this book is to help build social intelligence and perspective by creating a culture of appreciation and fostering a growth mind-set. Help is on the way!

If a Strengths Focus Is Key, Where Is the Training We Need?

I consider PMI, the largest professional organization of project managers in the world, to be the benchmark of the standards of the profession today. PMI and project managers as a profession acknowledge the importance of relationship management, engagement, and influence. But how much weight and support do we give to these concepts? How can we, as project managers, learn these new skills?

In the current edition of PMI’s Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge,26 the project manager’s guide to applying project management standards, tools, and techniques, there are over seven hundred pages27 of explanation of what a project manager needs to do to run a project successfully. According to PMI, “The project manager is successful when the project objectives have been achieved. Another aspect of success is stakeholder satisfaction. The project manager should address stakeholder needs, concerns and expectations to satisfy relevant stakeholders.”28

In the heart of the guide, there is one page29 about the necessary interpersonal skills of the project manager, as well as a new section on politics, power, and getting things done. The guide highlights that the best project managers are those who focus on relationship management and communication,30 and that the top project managers spend about 90 percent of their time on a project communicating.31

Within the accompanying Standard for Project Management,32 there is a list of eleven components of interpersonal skills. Each one is explained briefly within the standard. These are as follows:

1. Leadership

2. Team building

3. Motivation

4. Communication

5. Influencing

6. Decision making

7. Political and cultural awareness

8. Negotiation

9. Trust building

10. Conflict management

11. Coaching

These are all certainly critical interpersonal skills—for project managers and team members alike—but nowhere in the standard is there any guidance on how to develop those skills, what they look like when they are executed well, and what to do if you don’t have them. To be fair, PMI is an accreditation and professional networking body, not an educational organization; but in the accreditation process, how much is the capacity of the project manager to weave together a project team assessed?

The new talent triangle, introduced in 2014, also places much more emphasis on leadership; however, we are still left to develop the skills ourselves, and we receive little guidance on how to learn to lead. Where do we go to learn those skills? How do we become good leaders, coaches and mentors, influencers, and team builders?

Happily, as the respect and need for project managers have grown, the number of educational opportunities, including master’s programs, has increased. These programs in project management, at some great schools, still focus on the technicalities of the field.

A quick check of the curricula for some of the top schools reveals that a typical master’s program in project management entails thirty credits (although some schools look for forty-five to forty-eight) and that typically there are just three credits allotted to core classes such as Communication and Collaboration or Leadership and Teamwork. In other words, project management skills related to relationship building and communication are only 10 percent of the curriculum. This is despite the research showing that the most effective project managers are those who spend 90 percent of their time engaged in communication, and the top 2 percent are those who focus on relationships and communication.33

I believe that those who invest in a master’s program expect to go on to lead larger, more complex projects, where the eleven components of interpersonal skills can be expected to be even more critical, and yet here the training is least developed and mostly elective.

As your own experience likely confirms, there is ample evidence that a large proportion of projects are at best disappointing, and at worst a drain on resources that might have been better used elsewhere. We can never get back those hours or dollars that are spent on projects that are canceled or that overrun. If those failures are used to really learn about what works and what does not, there is value in them, but traditional “lessons learned” reporting is backward looking and not forward looking. Rarely have I seen an organization or project management office take a forward look to anticipate how to change the process in future projects to avoid the mistakes of the past. In the best cases, we learn from those mistakes and select and run better projects in the future, but all too often we don’t learn the best lessons and are doomed to repeat the same mistakes on another project.

All too often, projects are, in the words of Shirley Bassey, Welsh singer, “just a little bit of history repeating!”34

Looking at the broader question of team member well-being, engagement, and commitment, the studies highlight that employees remain disengaged and disconnected from their roles, colleagues, and work life. Many of our team members appear to be putting in the bare minimum to make it through the work-day.

Others are actively interfering with our progress.

Despite all the depressing statistics, the news is good.

• People believe project managers are necessary.

• Project managers believe engagement is important and that they have a role in building it.

• Project managers are ready to learn more.

• There are some simple steps to building engagement for anyone who wants to learn, practice, and apply the techniques.

• Project managers already have some superpowers to assist them.

• Engaged employees are motivated employees, and motivated employees get stuff done!

1. How does your organization view the role of the project manager?

2. What do you believe your role is in building engagement?

3. How engaged are you?

4. What strengths do you already have?

5. What do you want to learn about now?

Strategies for Success

1. Be hopeful: You will be the type of project manager who builds great teams.

2. Be strong: How can you leverage your strengths for the benefit of the team?

3. Be brave: Try new things to help the team bond and grow.

4. Be curious: What questions will you ask to find out what your team wants and needs?

That is because engagement applies to you as much as any other employee. In fact, in project teams, I contend that team engagement and motivation start with project manager engagement and motivation.

It starts with you!

1. A full report of my survey is available here: Ruth Pearce, The Project Management Effect—2016 Survey (ALLE, 2017), http://alle4you.com/Blog/2016-project-manager-effect-survey/.

2. For evidence, see later in this chapter.

3. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017), 61.

4. Project Management Institute, The High Cost of Low Performance: How Will You Improve Business Results?, 2016 Pulse of the Profession Report (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2016), 5, http://www.pmi.org/learning/thought-leadership/pulse/pulse-of-the-profession-2016.

5. Project Management Institute, Success Rates Rise: Transforming the High Cost of Low Performance, 2017 Pulse of the Profession Report (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2016), 2, https://www.pmi.org/learning/thought-leadership/pulse/pulse-of-the-profession-2017.

6. Project Management Institute, Project Management between 2010 + 2020, 2013 Project Management Talent Gap Report (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2013), 2, http://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/business-solutions/project-management-skills-gap-report.pdf.

7. For further information on the survey conducted, please contact the author.

8. Gallup, State of the Global Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders Worldwide, 2013 report (Washington, DC: Gallup, 2013), 17.

9. Project Management Institute, 716.

10. Gallup, State of the Global Workplace, 42.

11. Gallup, State of the Global Workplace, 7, 83.

12. Gallup, 17.

13. Gallup, 12.

14. Gallup, 17.

15. Brandon Rigoni and Jim Asplund, “Strengths-Based Employee Development: The Business Results,” Gallup, July 7, 2016, http://www.gallup.com/businessjournal/193499/strengths-based-employee-developmentbusiness-results.aspx.

16. L. C. Hone, A. Jarden, S. Duncan, and G. M. Schofield, “Flourishing in New Zealand Workers: Associations with Lifestyle Behaviors, Physical Health, Psychosocial, and Work-Related Indicators,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 57, no. 9 (2015): 973–983.

17. At this early stage of the research, I took any difference that was equal to or greater than one corrected standard deviation to be significant. As long as this is a normal distribution, then 95 percent of project managers can be expected to lie within two standard deviations of the mean.

18. Christopher Peterson and Martin E. P. Seligman, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

19. S. J. Lopez, Making Hope Happen: Create the Future You Want for Yourself and Others (New York: Atria Paperback, 2014).

20. Robert E. McGrath, “Character Strengths in 75 Nations: An Update,” Journal of Positive Psychology 10, no. 1 (2015): 41–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888580.

21. In the future, I hope to do more research, with a larger sample, into the hypothesis that hope, love of learning, and possibly appreciation of beauty and prudence are related to the selection of project manager as a job.

22. For those of you who are familiar with statistical analysis, hope has a corrected standard deviation of 6.3, and love of learning has a standard deviation of 7.5.

23. VIA Institute on Character, “Love of Learning,” accessed June 7, 2018, http://www.viacharacter.org/www/Character-Strengths/Love-of-Learning.

24. Andy Crowe, Alpha Project Managers: What the Top 2% Know That Everyone Else Does Not (Kennesaw, GA: Velociteach, 2016), 83, 85.

25. As with the more highly ranked strengths, I would like to perform more research on a larger sample to determine whether this difference indicates a significant difference between project managers and the population as a whole.

26. Project Management Institute, PMBOK Guide.

27. Increased from 413 pages in the previous edition.

28. Project Management Institute, PMBOK Guide, 552.

29. Project Management Institute, 61.

30. Project Management Institute, 57.

31. This statistic is taken from Crowe, Alpha Project Managers, 83.

32. Project Management Institute, PMBOK Guide, 539–635.

33. Crowe, Alpha Project Managers, 83.

34. “History Repeating,” featuring Shirley Bassey, by Alex Gifford, on Propeller-heads, History Repeating, Wall of Sound WALLT036, 1997, 33 1/3 rpm.