Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Completing Capitalism

Heal Business to Heal the World

Bruno Roche (Author) | Jay Jakub (Author) | Colin Mayer (Foreword by) | Martin Radvan (Foreword by)

Publication date: 05/01/2017

For the past fifty years, leaders in the business world have believed that their sole responsibility is to maximize profit for shareholders. But this obsessive focus was a major cause of the abuses that nearly sunk the global economy in 2008. In this analytically rigorous and eminently practical book, Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub offer a more complete form of capitalism, one that delivers superior financial performance precisely because it mobilizes and generates human, social, and natural capital along with financial capital. They describe how the model has been implemented in live business pilots in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. Recent high-profile books like Capital in the Twenty-First Century have exposed financial capitalism's shortcomings, but this book goes far beyond by describing a well-developed, field-tested alternative.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

For the past fifty years, leaders in the business world have believed that their sole responsibility is to maximize profit for shareholders. But this obsessive focus was a major cause of the abuses that nearly sunk the global economy in 2008. In this analytically rigorous and eminently practical book, Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub offer a more complete form of capitalism, one that delivers superior financial performance precisely because it mobilizes and generates human, social, and natural capital along with financial capital. They describe how the model has been implemented in live business pilots in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. Recent high-profile books like Capital in the Twenty-First Century have exposed financial capitalism's shortcomings, but this book goes far beyond by describing a well-developed, field-tested alternative.

—Peter Block, author of Flawless Consulting and Community

“The world is rapidly changing, and business must adapt to the new rules of the game or fall behind. Roche and Jakub give us a blueprint for sustainable corporate prosperity. It's an approach that can deliver greater value to society and the environment and also deliver superior business returns—a ‘win-win-win' for all stakeholders in a corporate value chain. But to do this, you must work with the right people. This new way of operating a business is applicable to all sectors of the economy. It is not just about doing good but is good for business.”

—Olivier Goudet, CEO, JAB Group, and Chairman, Anheuser-Busch InBev

“Courageously reconciles dimensions that were thought to be mutually exclusive for centuries. A must-read for today's business leaders who are ready to reinvent their world!”

—Jean-Christophe Flatin, President, Mars Global Chocolate

“In Completing Capitalism, Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub dramatically succeed where others have dismally failed. Their clear, concise, values-driven words shape capitalism into its final form and elevate it to the pinnacle position that it deserves. Roche's and Jakub's superb scholarship is underpinned and supported by the practical reality of successful pilots and business world applications. They not only complete capitalism, they create and hand us a road map for responsible business in the 21st century.”

—Dr. Frank Akers, former Associate Director, Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Chairman, Mars Science Advisory Council; CEO, Oak Ridge Strategies Group; and Brigadier General, US Army (ret.)

“For Veolia, the world leader in environmental services, the question of innovation in service of human progress is central: expanding access to natural resources, preserving and renewing them is our vocation. Our values at Veolia are in profound harmony with the great essay of Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub, Completing Capitalism, which proposes a vision and practical solutions for a responsible capitalism based on reciprocity and shared prosperity.”

—Dinah Louda, Executive Director, Veolia Institute, and advisor to the CEO of Veolia

“The more complete form of capitalism put forward by Roche and Jakub is not about competitive advantage. But to be competitive in the future, companies will need to operate this way.”

—Paul Michaels, former CEO, Mars, Incorporated, and former executive, Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble

“As human beings we long for the way the world is supposed to be, even as we make choices against that hope. For years Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub have been hard at work thinking and rethinking the way that business should be and ought to be—if we are to flourish as selves and societies, choosing a future that understands the grain of the universe. With a rare willingness to ask the most critical questions about the nature of business, their ‘economics of mutuality' is a vision for doing good and doing well in the context of one of the most iconic brands in the modern world. Neither charity nor corporate social responsibility, but rather a way for sustained profitability, Completing Capitalism argues for making money in a way that remembers the meaning of the marketplace.”

—Dr. Steven Garber, Principal, The Washington Institute, and author of Visions of Vocation and The Fabric of Faithfulness

“Some endeavors require intellectual, emotional, or spiritual courage. Bruno and Jay have demonstrated all three in fleshing out this valuable piece of work on behalf of Mars, Incorporated, our associates, and all stakeholders, including the planet. I truly hope it evolves, as I believe it can and must, the dialogue regarding capitalism's future and its crucial role in our world going forward.”

—Stephen Badger, Chairman of the Board, Mars, Incorporated

“This crisis is more than a ‘normal' crisis. It requires a reset of our thoughts and ways of doing. Business as usual does not work anymore or anywhere. The journey that Jay Jakub and Bruno Roche are proposing is a difficult one but a promising and fecund one. It is ambitious but within our reach to make this world a better one. This is, I believe, the only reasonable option. We have patched up the system. This is the good news. We have to rebuild. This is the promising appeal. A properly functioning market economy must work for the many, not just for the few. Now is the time if we want to eradicate poverty in our generation. And here is how.”

—Bertrand Badré, CEO, BlueOrange Capital; Chair, Global Future Council on International Governance and Public-Private Cooperation, World Economic Forum; former Managing Director and Chief Financial Officer, World Bank Group; and former Group Chief Financial Officer, Société Générale and Crédit Agricole

Chapter 1

The Expanded Meaning of Capital

All truth passes through three stages. First it is ridiculed. Second it is violently opposed. Third it is accepted as being self-evident.

—Arthur Schopenhauer, German philosopher

We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

—Albert Einstein

When we started our new business model research in 2007, more than a year before the 2008 global economic crisis, our intuition was that the financial capitalism approach of Milton Friedman would soon reach its limits and needed to be reformed and made more complete in order for the economy and business to continue to create value.

The 2008 crisis wake-up call and a growing sense of urgency

In the years since the 2008 crisis, what began as intuition on our part has been dramatically confirmed as fact. The long-accepted (by business) Friedmanic assumption that the sole social responsibility of business is to maximize profit to maximize shareholder value—combined with the pressure of financial capital on business operations and the primacy of short-term financial capital creation over other forms of capital—is viewed by a growing number of stakeholders as being obsolete or no longer fitting for today’s economic, social, and environmental context.

Perhaps those who enacted Friedman’s views on a wide scale in ways that may have gone beyond his intent were more responsible than the man himself for the distorted form of incomplete capitalism bearing his name that we have today. Friedman’s writings, after all, do reflect a recognition that some form of social expenditures are necessary to maximize the long-term profitability of a company. Yet, this seems to have been largely ignored by most who adopted Friedman’s model, and the focus—short or long—remains fixed upon maximizing just one form of capital: money. And that is the point that truly matters—acknowledging what Friedman’s adherents have done through their single-minded focus on that one form of capital, and what they and others must now accept if capitalism is to become functional and not create even greater dysfunction or be discarded completely for any number of inferior alternatives that could inflict their own dysfunctions on the world.

We are pleased to observe that partly as a result of the wakeup call of the 2008 crisis, there is now a growing and active move-ment—though still largely disparate and chaotic, made up of a relatively small number of businesses, NGOs, and a handful of academics—that challenges the hypothesis of Chicago. Some of these go by various monikers like conscious capitalism, inclusive capitalism, the triple bottom line, creating shared value, and the B Corp movement. In some instances they even predate the 2008 crisis, like the Social Venture Network, though the magnitude and continuing effects of 2008 helped make the world more open to discussing the current system’s shortcomings.

We have no doubt that something good will emerge from this rising awareness. But at the same time, we wonder whether it will be enough—and come quickly enough—to mitigate the most destructive aspects of the pain associated with the economic transition that will come when the current system goes from being dysfunctional to nonfunctioning, as nearly happened in 2008. We don’t know the answer to these questions of timing and acceptance, but we feel a strong and growing sense of urgency to share what we have learned about what a more complete form of capitalism could look like, despite the fact that we are still very much on a journey with this work.

Contrary to what happened in 1989 when the Berlin Wall collapsed almost overnight, where the alternative to the Marxist model (the market economy) was already in place in the Western world and ready to take over, the next model that will succeed financial capitalism is not yet in place. Hence, if Wall Street “collapses” in its own way, suddenly like the Berlin Wall did, we don’t yet have an accepted alternative to embrace.

The role of global corporations in the development and enactment of a new model

Since business has historically been the driving force that has brought prosperity and taken millions of people out of poverty, and major corporations today have more power than some governments, we asked ourselves, “What would or should be the role and responsibility of large multinational firms in the coming transition from one system to the next?” And we asked how large multinational firms could help give birth to a new, more balanced approach to value creation and value sharing in terms of deploying a new model on a large scale.

Our intuition has been that a model based on the fair sharing of benefits among all stakeholders would create greater, more holistic, measurable value. Such a model, in turn, will necessarily lead to a superior approach for business than the model currently in place most everywhere. But we had to prove it.

Implicit principle needing to be explicit

The business principle that the sharing of benefits across stakeholders could lead to superior business performance over that of maximizing benefits to shareholders has only been implicitly enacted in some successful businesses over the last century or so. But it has not yet been translated into an explicit management theory. It is still more of a selective management philosophy than a scientifically rigorous management methodology that can be more widely deployed. Part of the explanation for this is that prior to the latest crisis, which exposed major underlying weaknesses in the financial capitalism model, most business managers and MBA educators were still too deeply rooted in their belief in the superiority of Friedman’s approach to think much beyond it, other than perhaps in relatively narrow, ideological ways. Of course, there are always some exceptions, but none have as yet been simple, scalable, and compelling enough to be transformational.

In 2007, we sensed it was not only possible but also critically important to make this implicit management philosophy more explicit; to translate it into a true management theory. This was because we saw the global economic system as being on the brink of a systemic shift, with most businesses woefully unprepared. Making the implicit more explicit was not going to be easy, as it required developing new metrics for the different forms of nonfinancial capital, along with new management practices, and verifying through rigorous business experiments whether and how this approach can indeed create superior value for all—more than a profit maximization approach. The 2008 crisis brought a welcome new atmosphere of open-mindedness among some business managers and business educators that enabled us to proceed in earnest.

No relationship between profit and growth: a natural law or a worrying outcome of ideology?

To our surprise, our initial research into the management literature highlighted that the questions of “the right level of profit,” or whether business should just be about shareholder profit, or whether greater sharing among stakeholders can deliver superior performance over time, have not been addressed rigorously or systematically. With the exception of a handful of papers and case studies, some of which have been only recently published, we found no truly rigorous approach or framework to address this question in a meaningful way.

This space today, again with very few exceptions, essentially constitutes a green field in the literature. This gap in the literature is in and of itself a remarkable circumstance, suggesting a vacuum in economic thinking that underscores the overwhelming influence of the Chicago school, even with all its now obvious dysfunctions becoming more visible to those who look for them. But it is sometimes difficult to see the forest for the trees, especially when our business schools and corporations are nearly all in lockstep in focusing only on trees.

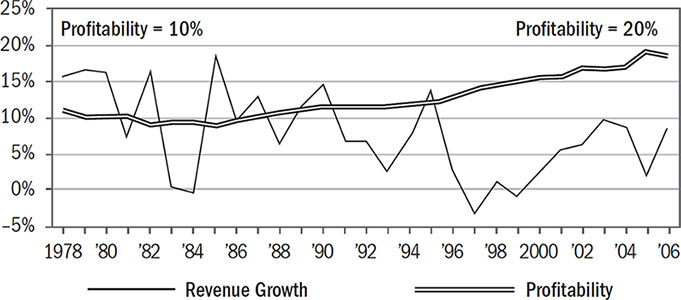

Consequently, we conducted extensive empirical research into the actual performance of more than 3,500 companies (public and private, across different geographies) over roughly a three-decade span (1978–2006) leading up to the kickoff of our business model research program in early 2007. Our purpose was simply to study the causal relationship between profit and growth, i.e., between past profit and future growth, between past growth and future profit, between past growth and future growth, and between past profit and future profit, all over different time scales. The results highlighted a surprising pattern. We found no causal relationship between profit and growth, and no causal relationship between past growth and future growth—regardless of the time scale. The only strong causal relationship we found, in fact, was between past profit and future profit, implying that the only long-lasting pattern in business is its ability to generate profit—irrespective of its top line. A striking and surprising result.

Looking further into a subset of the sample data we examined—focusing on FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) players (see figure 1)—we highlighted that while growth has been volatile (with ups and downs) over time, profitability during the same time span has steadily and consistently increased. In other words, consistently rising profits have been achieved by thousands of companies over the past few decades in both high and low-growth scenarios. High profits did not inhibit or promote growth. High-profit businesses, in fact, apparently can live together with sluggish growth. Low growth is sustainable. Low profit, however, is not sustainable. It is remarkable that this pattern held during the 2008 global economic crisis, during which many corporate top lines plummeted while profit continued to increase (though only slightly), hence, securing the continuing remuneration of shareholders whatever the underlying economic context.

These facts appear to validate Friedman’s assertion that the only worthwhile goal is to maximize profits, and the role of management, therefore, has implicitly been focused on driving up bottom line net earnings (extracting increasingly more value over time) rather than on managing top line gross revenue, which is more prone to external economic fluctuations. One could argue of course that the increased profitability observed across firms over roughly the last thirty years has actually been driven by rising productivity and accelerating technological change. However, the steadily falling labor share 1 in large economies since the 1980s, as pointed out in a recent paper by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), 2 suggests the opposite. Over the last three decades, in a majority of large economies, including the United States, Germany, and Japan, wage growth has actually been lagging behind productivity growth, and labor productivity has outpaced real average wage growth.

Figure 1. Profitability and growth of the top FMCG companies over a three-decade span.

Furthermore, the steady increase of the so-called “ecological footprint” of human activities reveals that the world now uses the equivalent of at least 1.6 planets to provide the natural resources it needs to operate versus 1.0 planets in 1970, around the time Friedman’s model was invented and began to gain more widespread acceptance in business. 3 The productivity gains have not translated into higher remuneration of the planet and the people, but rather have provided greater benefits to shareholders who own the financial capital.

This rather new phenomenon—the lower pre-1970s ecological footprint and the fact that income flowing to labor and financial capital was more or less fixed for decades prior to the dramatic tilt toward the latter in the 1980s—raises a bigger question about whether profit maximization is a natural law or an ideology. And it also begs the question of whether this increase in profitability over time sustains or undermines Friedman’s approach, as earlier noted. Being able to outsource jobs to cheaper and cheaper labor markets to help drive the bottom line (net earnings) regardless of top line (gross sales) performance, after all, cannot continue indefinitely. One day there will be no cheaper labor market to which jobs can be outsourced, and the laws of supply and demand will drive up the cost to business of natural resources as the planet becomes more and more depleted. Such is the way of new forms of scarcity that were not present at the birth of Friedman’s model.

Figure 1 illustrates that on average, the profitability (bottom line) of the top FMCG companies doubled over the thirty-year period we examined, while revenue growth (top line) was highly cyclical, hence, there is little evidence of any meaningful relationship between the top and bottom lines, only between past and future profit. Thus, it is the Friedmanic ideology, underpinned by management practices and metrics that only drive the bottom line, acting as the profit engine for business—but only for as long as labor and natural resources remain roughly in status quo, which is no longer the case.

Going beyond traditional boundaries and financial capital to measure performance

The need to extend the firm’s responsibility beyond its traditional legal boundaries is driven by the fact that most businesses increasingly operate within complex value chains, made of business players of different sizes, operating in different geographies. Metaphorically, one could therefore argue that nowadays each business value chain is only as strong as its weakest link. And responsible, more mutually beneficial business practice is about ensuring that the weakest links of the value chain do not become weaker, but rather are strengthened because the financial cost incurred by a disruption of a value chain is frequently much higher than the cost of maintaining the strength of the weakest players in the value chain. Hence, it is important to embrace the entire business ecosystem in which a business operates, beyond the traditional legal boundaries of the firm. This includes identifying the weakest links and the most acute pain points across all forms of capital, setting up methodologies and metrics to account for them, fostering an environment that is conducive to investing in strengthening those weakest links, and giving them the means to invest and grow (by offering higher margins, as one example among others).

In the same way that economics essentially is the management of scarcity, management is predominantly about measurement. Hence, there is a need to translate the concept of changing various forms of scarcity into the managerial area and to develop new performance metrics for the other forms of capital we discuss in detail in this book (social, human, natural). The idea is to manage the new forms of scarcity and to account for the nonfinancial riches (in nonfinancial ways) that have heretofore been “hidden in plain sight” because of their prior overabundance, yet they have always been critically important for the sustainable performance of any business.

Because the metrics for nonfinancial forms of capital (social, human, natural) have in the context of business application been comparatively weak, confusing, or even nonexistent in some instances, the easiest and most obvious form of capital to measure has been money. This, in turn, has convinced many who are moving into this multi-capital space of research—especially those engaged in management consulting—to simply monetize the other forms of capital in order to deal, eventually, with one metric. This is despite the (obvious to us) fact that monetizing everything may be counterproductive and will certainly be inaccurate, as how can one put a dollar figure on community trust, for example? Or on managers walking the talk of the values they espouse? As we know from history, human nature often follows a path of least resistance, following the logic of Occam’s razor, where the simplest explanation or solution is usually superior. In this case, monetizing may seem relatively simple on the surface, but it will be distorting in ways we will later discuss in the chapters on each nonfinancial form of capital.

From the perspective of what constitutes “value” in a business context, the planet provides the resources with which business makes products. The people transform those resources into the actual products and services. The money provides the liquidity to enable people to affect the transformation. This is consistent with the core principles of economic history we noted in the introduction.

The overabundance of money in the system

As stated previously, our argument is that if economics essentially is the management of scarcity, then there is no need to overly focus on financial capital alone because, while money was scarce in the postwar period, this is no longer the case. In fact, if anything, the amount of financial capital that is allegedly currently in existence—we say allegedly because it is inconceivable that much of this financial capital exists as more than a bookkeeping exercise, especially in the case of derivatives valuation 4 —is almost unimaginable.

Since President Richard Nixon moved the US dollar off the gold standard in 1971, financial capital in the form of currency in circulation has been increasing. This occurred rather incrementally through the 1970s until the late 1980s, when the money supply began to grow at a faster rate. Picking up speed in the 1990s, the global money supply started to accelerate in the 2000s, but truly exploded following the 2008 global economic crisis, when developed economy governments simultaneously embarked on a radical expansionary monetary policy that has massively increased the amount of financial liquidity in the global economic system.

As one of many possible examples, through a policy called quantitative easing (QE), the US Federal Reserve has managed via three QE interventions since the 2008 crisis to “purchase” hundreds of billions of dollars in securities in its “open market operations,” according to the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in a 2015 report, “without any real assets, deposits, or money, bringing its total portfolio of securities acquired to $4.236 trillion at year end 2014.” By contrast, says AEI, the Federal Reserve’s total securities in 2007 were valued at $750 billion. And with the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the central banks of other leading economies joining the US Fed in doing their own multiple rounds of QE interventions following the 2008 financial crisis, the world is now literally awash in financial capital.

There is plenty of money in the world today, far too much in fact, but the flow of dollars, yen, euros, and pounds have unfortunately been accumulated by just a few in the financial system. This accumulation, in turn, has not translated efficiently into the real economy in terms of job creation, investment, or economic growth, making the gap between those wealthy few and the many poor grow ever wider. This gap has been exacerbated by the fact that the huge QE injections can most easily be absorbed through the financial markets that are dominated by the bigger players, hence, we see a continuing rise of the stock market indexes to breathtaking heights that brings with it a false sense of security for many that the economy must somehow be healthier than it is.

The hidden shortage of other forms of capital

In contrast to the bloated, still growing world money supply, the world’s nonfinancial resources (planet in the form of natural capital, and people in the form of human and social capital) are comparatively scarce and becoming more so. When we refer in this context to people, this is not in terms of numbers of workers, since the global population has now grown from about 3.8 billion in 1971 when the dollar ceased to be underpinned by gold, to about 7.4 billion in 2016. Rather, we mean those of working age having the right mix of skills and talent (human capital) and having the right social networks and community (social capital) for the upcoming challenges and the jobs that the new economy will produce and require. And when we speak of planet resources (natural capital), we refer to that which is now being depleted at an accelerating pace and can no longer sustain the current economic growth model. Natural capital is in urgent need of being treated as an increasingly scarce resource, and not as a form of free “renewable riches”—yet it is still essential to ensure a sustainable and healthy future, both for business operations and for mankind at large.

It now makes much more sense to us to change the focus from financial capital onto the management of the nonfinancial pillars of prosperity noted above, rather than continuing to generate excessive financial liquidity while largely ignoring the reality of the new forms of scarcity. To do otherwise would be hazardous. The big challenge we see, however, is mainly psychological in nature in that the paradigm for those who can most easily influence transformational change in the global economy because of where they are placed in that economy has not yet been altered, despite the lessons of 2008. Perhaps there is a sense among many that there is simply too much financial capital to be made to waste time considering the bigger picture. There remains among such elites an abiding impression that if financial capital is just managed more efficiently and maximized for shareholders, the rest of the system will find a way to take care of itself. We do not believe that it will be able to take care of itself, because the rules of the game have changed. The clock is ticking.

The need for new metrics as a foundation for establishing a new management methodology

We need, then, to develop a simple and coherent way to measure the value, impact, and benefits that accrue to the categories of people and planet for business. And we need to find a way for these new metrics—which contribute to defining a more complete form of capitalism—to become part of the management (operating system) of the firm.

We are not advocating a rebalancing or redistribution to overly favor just one of the other forms of capital—as some might advocate and have done so throughout history, with mixed results at best. For example, one alternative noted in our introduction might be to favor people at the expense of the planet and financial capital—the solution Karl Marx advocated and the Soviet Union under Lenin, Stalin, and their successors attempted in a distorted and ultimately very damaging manner. Another approach would be to favor the planet at the expense of financial capital and people, as some today advocate, such as the “degrowth” movement, which wants to downscale production and consumption, and to contract economies, based on the premise that overconsumption lies at the root of long-term environmental stress issues and social inequalities.

We argue that simply skewing the balance in favor of one category of capital at the expense of the other two foundational economic pillars is counterproductive over time. To do so would be a proverbial “half-truth” (a lie), albeit a seductive one since it is easy to say people matter most or that without a restoration of nature we are doomed to global affliction and ultimately to starvation. But it is only when all three pillars of prosperity are balanced—in terms of accounting for what each pillar contributes to the system and how each pillar is remunerated—will prosperity be lasting.

The temptation to do nothing and the imperative to act

Of course, it might be argued that the global economic system will change naturally (self-correct) when it needs to change, therefore, there is no need for man to be proactive. No doubt some people echoed this same “do nothing” refrain prior to the 1789 French Revolution, the 1917 Russian Revolution, the 1929 Wall Street crash, the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, the 2008 global economic meltdown, and the mass migration crisis affecting Europe and the Middle East that began in 2015, to name just a handful of the upheavals that have afflicted mankind. These transition moments have disrupted whole societies, creating much hardship, the intensity of which was due in large part because societies were unprepared. Perhaps some of the suffering of those periods in our history could have been made far less severe had the proverbial ostriches, heads buried in the sand of denial, been less dominant and therefore change could have taken place before crisis compelled it.

We assert that a new model can and must be evolved right now, and that this can be accomplished from the inside of business by a new generation of enlightened leaders who recognize both the limit of the current system and the potential of the system to be fixed and reoriented to other ends—managers and reformers who want to be empowered to leverage the power of business as a force for good, for a greater purpose, a purpose that inspires.

In the waning years of the former Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, who knew that the system he was leading was poised to collapse, had the courage to proactively reform and then abandon that system in ways intended to mitigate bloodshed, and he was largely able to do so. One can only imagine the intense and prolonged suffering that could have resulted had not Gorbachev chosen this pathway, with someone in his place choosing instead to use force to impose the collapsing Soviet system beyond its natural end point. Today, there may be many “business Gorbachevs” in the world, whose pro-activeness at this particular moment in history, and whose willingness to expedite transitioning business from the increasingly dysfunctional mono-capitalism of Friedman to a more holistic, complete capitalism such as we envision, could similarly mitigate some of the pain of that transition. But this can occur only if we act quickly, and decisively.

A pragmatic approach

We have worked in senior corporate positions for many years and fully value the positive changes to people’s lives that business creates. But the benefits of capitalism need to be expanded and shared for long-lasting, fully functional prosperity to occur for the many. And the failure of the current incomplete capitalist model to incentivize adequate sharing through broader measurement will ultimately (maybe sooner than most think) be its undoing.

We also appreciate the importance of capital concentration, but not in the hands of passive shareholders or for speculation purposes, but rather in the hands of talented entrepreneurs of a new kind who will invest in ways that will produce greater prosperity for all. Our assertion is that since there is the same proportion of entrepreneurs in every population (among the poor as well as the rich), the current system is far from efficiently allocating the capital in the hands of active entrepreneurs. The current mechanism of capital concentration is inefficient in our view and not only leads to unsustainable disparity, but it also prevents active entrepreneurs from accessing capital and leads to destruction of value, such as when useful capital is wasted by passive owners or is fueling financial bubbles instead of being invested in the real economy.

A counterintuitive moral perspective

Rampant inequalities among people constitute a structural reality and may actually not in every instance be inherently unjust, contrary to what many proponents of social justice may believe, but only if a sense of purpose can overcome the dysfunction of greed. This is a counterintuitive way of thinking for many social justice advocates, but one in which lessons for the future economic system can be gleaned.

The crux of our argument is that we all have access to different resources, have different skills, and have different forms of wealth at our disposal, defined not just in financial terms, but also by individual and social well-being, access to abundant natural resources, the gift of public speaking, teaching, of mathematics or science, of dancing, singing, drawing, building, whatever one’s special talent may be. Such differences, rather than being viewed as a form of injustice, might actually be better and more accurately viewed as an opportunity. An opportunity for those who have access to something others do not but could benefit from, to be connected with those who have what they may be missing and which they need. In a knowledge economy, where value is inherent not in the accumulation of a single form of capital like money, but rather in building relationships that give one access to the knowledge or other missing ingredients one can use to prosper in different ways, such exchange relationships could be a powerful way to advance social justice without defaulting to redistribution as the only means to do so.

A truly moral system of exchange, however, must be capable of acknowledging and measuring (so that it can be managed in a business sense) the inherent value of different forms of contribution. This would empower each individual involved to maximize the utility of what he or she has received in terms of abilities to fulfill his or her own destiny, while improving the lives of others in the process of pursuing that destiny. In such a context, some concentration of capital in the hands of talented entrepreneurs—in individuals who have the skills to grow whatever forms of capital they are endowed with—is not only a business imperative but can also be a moral act (or at a minimum, not an amoral one) that should be encouraged, as it can be a very efficient way of creating and sharing greater holistic value, playing to the particular strengths of each individual.

Against the backdrop of widening wealth disparity and the injustice of expanding poverty, the notion that prosperity can come from giving more to the one who already has and taking from the one who has less will likely go against the grain for many who are considering it for the first time. But it is not a new concept; far from it. In fact, it is a concept that has been part of the moral foundation of the Western world for several millennia, as illustrated by the ancient parable of the talents or minas (forms of ancient currency, of silver or gold).

In this very old parable, one man was given by his employer five talents (or minas), another two, and a third a single talent to safeguard while the employer was away. The man with five traded for five additional talents, doubling the money he was entrusted with, while the man with two also doubled his money by gaining two more through investment. But the third man, fearing the wrath of his employer, buried his talent to protect it, fearing what would happen if it was lost or squandered, and therefore gained nothing. The third man did, however, earn the rebuke of his returning employer for failing to invest what had been entrusted to him. The parable ends with the third man’s talent being confiscated and given to the man who invested the most—the entrepreneur—whose behavior can be interpreted as a form of proactive skillful stewardship of resources. The idleness or lack of effective stewardship by the one who was given the single talent resulted in forfeiture. We are all expected to do our part with what we are given, be this a dollar or a skill, and in an economy that values all forms of capital rather than just one form (money), good stewardship takes on expanded meaning. Hence, financial capital need not necessarily be redistributed evenly to the proactive and idle alike to bring fairness or justice.

This timeless story is very meaningful to us because it goes far beyond narrow ideologies arguing for confiscation and redistribution, or for incentivizing individuals to take and accumulate excessively for their benefit alone. And by so doing, it reveals a narrow pathway to a broader prosperity that can be achieved through leveraging each of our individual gifts, whatever they may be. It illustrates the moral and business principle to give each person, in each generation, the opportunity to prosper, and to concentrate the resources in each generation among those who have the abilities necessary to prosper it.

But this must be done not just for individual gain, but for the greater good, and we will show in this book how applying such an approach can in fact create greater benefits for all, including for the individual contributor who might otherwise focus on squeezing as much profit for himself out of the others. Hence, the pearl of wisdom of King Solomon, whom we quoted in the introduction as having said (in a slightly different form) “one can give freely, but gain more, but another can withhold unduly, yet come to poverty, with the generous person prospering, and whomever refreshes others will be refreshed.” These are not just empty words, as we have experimented with this concept and have experienced such outcomes, however unorthodox they may at first appear in the context of the Friedmanic system in place today.

A new methodology for a new paradigm

Given the background above, the first stage of the project we began in 2007 involved identifying the criteria to measure performance/success that puts a premium on relationships, access, and resource efficiency rather than on accumulation of money alone—based on the assumption that the only truly robust set of metrics used today in business are financial performance related. Our research has revealed that while performance measurements for the return on financial capital are robust and effective, the performance measurement of the other two pillars of value creation—planet and people—do exist to some extent, but are currently quite rudimentary, disparate, and not directly actionable in a business model context.

Current planet metrics are rudimentary, focused on external reporting rather than resource efficiency

The planet metrics most used by business, such as carbon footprint or greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), are meant more for external reporting or benchmarking purposes rather than for management action at a business unit level. Companies that emit damaging levels of carbon, after all, have the option under international agreements like the Kyoto Protocol of purchasing carbon credits to at least notionally offset the impact of CO2 emissions, leaving them free to continue emitting carbon at previous levels if they so choose by paying a relatively small premium for this right. And newer concepts, such as biodiversity offsetting, habitat services, and mitigation banking, to name a few, do not take us much beyond GHG.

Such external-type “output” metrics, in our view, are really aimed at helping a company conform to industry standards for doing “less bad.” These metrics also do not have the same level of relevance across industries. For commodities like the manufacture of coffee, for example, measuring carbon footprint is of little use—except perhaps in the case of measuring carbon related solely to transport and distribution. This is because there is actually very little carbon generated in coffee production, including coffee packaging.

By contrast, we are more interested in a business model approach that delivers a management metric or tool for natural capital that can help managers drive greater resource efficiency. Through this enhanced efficiency of inputs rather than focusing just on outputs (footprint), we are seeking to deliver superior business and environmental performance simultaneously. Both the input and output approaches have their uses and are not mutually exclusive by any means, though they have very different purposes and audiences.

While it is an inherently “good thing” to measure and attempt to reduce industrial GHG, CO2 measurement is not aimed at, nor will it meaningfully directly impact, the resource efficiency of a company. It can be and is used more as a CSR effort or sustainability expense that can do some good in terms of environmental impact. It is also less likely to drive changes in the behavior of business managers beyond that aimed at enhancing corporate reputation, whereas driving managerial behavioral change is the key objective of our new business model agenda. Isolating which of the emissions are most harmful, what is the exact cause, and what can be done about it, moreover, is more difficult to achieve on the grand scale required to have a chance of restoring the environment to good health. GHG strategies are certainly not transformational for business, which is the place that could have more positive impact for the environment than any other if shown how reducing the use of natural resources can create more business value.

For example, we learned from our environmental thought partners and from what we read from other experts who work extensively in the environmental sustainability space that approximately 39,000 gallons of water (147,000 liters) are used in the production of every car made (on average) and 1,800 gallons of water (6,800 liters) are required to grow enough cotton to produce just one pair of blue jeans. 5 Similar statistics can be found for nearly every crop grown and almost every product manufactured. We also learned that intensive farming methods cause soil erosion and land depletion (Australia loses about 500m2of farmland every day because of salt rising through the soil), 6 and the world’s leading environmental researchers say air pollution is an increasing danger that will bring with it global warming. We don’t dispute any of this and see value in it, though always at a cost, i.e., trading profit for a measure of environmental good, which has no obvious or measurable return on investment for business beyond compliance with government regulation or a more abstract reputational benefit that is very hard to quantify. And without a solid return on investment, can such programs be truly game changing?

Knowing these planet-related statistics and reading about inspirational but mostly anecdotal CSR and environmental sustainability stories published in annual company reports, in our opinion, simply does not provide the necessary leverage for transformational change of business behavior to occur. This is because business managers and their shareholders need more than a simple tradeoff of profit, which they value, for doing some good for others, which they don’t value nearly as much. Satisfying government regulators or pressure groups that may be generating bad publicity, or spending a little more on occasion to show shareholders, customers, and consumers that a company is more responsible than the competition, or even because supply chains are no longer secure, are good things, but they are not enough. What businesses really need to be convinced that doing good need not always be a tradeoff for profit, but instead can actually lead to better performance overall, is a robust model that can help them evaluate (at a granular level) what they use and how they use it. This would enable them to make informed decisions and more efficient use of limited resources that can no longer replenish themselves naturally at sufficient rates to compensate for growing resource consumption.

A growing body of knowledge (which we leverage in our model) is developing about the environmental impact of granular (highly detailed) business activities at the business unit level. This is making it possible to run natural capital audits across any supply chain—and to identify the tension points and places where a business can intervene to meaningful effect. We will discuss this approach in detail in chapter 4.

People metrics, disparate and rudimentary, are also more about reporting and benchmarking

A very common type of metric for people at the individual level that we can find in the management literature and in business practices focuses on measuring engagement and well-being at work. The very well-known Gallup Q12 Employee Engagement Survey, for example, covers such broad topics as whether employees know what they are to do and have the necessary means, equipment, and support to do it, or whether they have recently received recognition or praise, indications that they feel cared for, encouraged, or valued. All laudable and interesting proxies to annually test the pulse of the workforce, but in our opinion, basic survey questions such as these comprise an incomplete, and even sometimes misleading proxy for well-being and employee engagement that only lightly scratches the surface of identifying the true drivers of employee workplace well-being.

More importantly, the extent to which companies can be tempted to use this engagement metric as a standalone instrument for employee well-being—because it is simple to administer, and in the absence of anything obvious that is more robust—suggests to us that added metrics are needed to be impactful in ways that can ultimately transform business behavior. A mix of people metrics would enable human resource professionals to craft interventions that will result in a more meaningful impact on employee well-being. This, by extension, can drive greater engagement and with it, better performance, talent attraction, and retention of the best and brightest.

Management metrics vs. reporting metrics

The crux of our argument is that, while it can be useful to have such broad indicators as GHG emissions for the environment—especially for external reporting purposes—and Gallup Q12 engagement scores to check the mood of the workplace from time to time, it is much more practical from a business management perspective to understand the key factors that tend to make production more resource efficient and that tend to increase people’s well-being at work and make them happier and more productive, respectively. And we also need to know whether these factors can be qualitatively calibrated across different organizations, countries, and cultures, given the marked variations that often occur across these various boundaries.

External vs. internal business metrics

Broadly speaking, business metrics are either external indicators used for reporting and benchmarking or internal indicators that support management decisions. The former, which speak to the world and include such metrics as NSV (net sales value—i.e., sales less returns, cost of damaged or missing goods, and discounts), cash, earnings, EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization—i.e., operating performance absent financing and accounting decisions or tax environments), and GHG (greenhouse gas emissions) are mostly what are called lagging performance indicators. Lagging indicators are mostly about outputs and tend to be fairly simple to measure but hard to impact. They are typically endorsed by external stakeholders, standardized across industries, actionable as an external reporting tool at an aggregated level, and most often communicated via financial and CSR reports.

Internal indicators, by contrast, function mostly as what are called leading performance indicators, which tend to be harder to measure but easier to impact than lagging indicators. Leading indicators speak to the company in its own language, such as through the metrics of ROTA (return on total assets—i.e., the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes against total net assets) and MAC (margin after conversion—i.e., percentage of profit after reducing net sales by prime and conversion costs, showing the relationship between selling price and cost of good). Such internal indicators aim to reflect the distinctive way companies and their like-purposed partners do business (based on culture and values) and support ways of working at the business unit level.

The nonfinancial metrics in the model we propose are of the internal or leading variety, and can be enacted only through a modified business model approach. This makes them potentially transformational for how businesses manage themselves in more mutually beneficial ways for stakeholders. Both leading and lagging types of metrics, however, are required to operate effectively. The nonfinancial metrics are designed essentially to help management do well by doing good, at scale. Or put another way, they are designed to entice business through its self-interest to transition from the narrow objective of maximizing shareholder profit to being global agents for change. Once business is equipped with the tools and practices that will enable it to be profitable by doing good rather than in spite of doing good (or not doing good at all), business leaders can begin to go far beyond Friedman’s maxim of the sole social responsibility of business is to maximize shareholder profit and into the realm of revitalizing communities, growing well-being, and restoring the environment on a broad scale.

External metrics are designed to communicate outside the company, but also to compare the company to other players. The model of “completed capitalism” focuses on designing internal metrics that are aligned with a corporation’s culture/DNA, can be enacted at the business unit level to help management make sound decisions, and are meaningful to stakeholders across any and every value chain.

Thought-partnering

To begin the process of calibrating the measures that would generate the maximum leverage, we partnered with some of the world’s leading thinkers and academic institutions. These included professors from Harvard Business School, Columbia University, Boston University, Stanford, the Paris School of Economics, the Sorbonne, the University of Wisconsin, New York University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the International Institute for Management Development (IMD-Lausanne), the Wuppertal Institute in Germany, Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Statistique et d’Economie Appliquée in Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Ateneo de Manila in the Philippines, the University of Indonesia, and Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, among others. Our aim was to build on the latest research to identify the key metrics that would help any business in any sector measure its business performance in relation to the way benefits are shared throughout the value chain.

Developing the new model as a non-rival good

Our model for profitable and sustainable operations focused first and foremost on areas of interest to the company that employs us—but we always held in our minds, and explained to our management team, the need for this model to be easily applicable to other companies and sectors, and openly available to all. In our opinion, a mutually beneficial business model would be much more useful to our company if many were operating in a similar manner than if we were a solo act. In the business vernacular, this would be called a “non-rival” or even an “anti-rival” good rather than intellectual property.

A rival good can only be used by one entity, be it an individual or a company. In a business context, it is normally characterized as providing a form of competitive advantage to the user, who seeks to deny its use by others. A non-rival good (or its extended form, called an anti-rival good), by contrast, derives its value from its use by others, not from its exclusivity, hence, a good deemed to be non- or anti-rival must be shared to bring maximum benefits.

An example of a rival good could be a consumable food item, which only really benefits the person eating it, or a tool like a screwdriver that can only be used by one person at a time. A non-rival good, by contrast, could be the Internet, where use by many brings more benefits to each individual user than would be the case if only one person or entity used it in a closed manner. The fact of our new business model being a non-rival or even an anti-rival good is why we took the decision early on—supported by our employers—to openly share what we were learning about how our new metrics and model can drive enhanced performance, measurable across multiple forms of capital in ways that deliver more mutual outcomes for stakeholders in any given value chain.

A model that truly can make more complete what is currently a dysfunctional, incomplete form of capitalism can only be usefully enacted at scale, across many companies and organizations whose shared collective experiences with the approach will grow, refine, and enhance the value of lessons about management practices that deliver mutual benefits. This is why we are now aiming to construct an open collaborative platform approach to the next phase of our work on the model, so that other MNCs—and eventually SMEs (small- and medium-size enterprises), NGOs, foundations, international and academic institutions, and others—can partner with us and with one another within their own particular business ecosystems. In a very mutual way, we can through such a platform share what we have learned to date, and harvest lessons and data from new piloting experiments that will help us all build a more compelling case for a wider rollout of the approach. There is time to keep the proverbial “light under the bushel” when that light provides competitive advantage, and there is a time to take the light out from under the bushel when sharing brings more value. To paraphrase our former CEO, who served as a mentor to us and was a core sponsor of our work, “[your new model] is not about competitive advantage, but to remain competitive in the future, [companies] will have to do this.”

We looked at the various parties along the value chain (farmer, supplier, manufacturer, distributor, consumer) and asked how each party was remunerated in terms of the various types of capital we have earlier outlined: human, social, natural, and shared financial. We then determined two broad categories for research: performance metrics that span the various forms of capital beyond just financial, and management practices that can deliver more mutual outcomes for stakeholders in a business value chain.

The performance metrics we developed are based on a set of approximately fifteen variables covering all the forms of capital we address. They have been proven through field-testing to be accurate enough (covering approximately 75 percent of the information—sufficiently robust to be actionable for business), and are thus very stable across business situations. The necessary data will eventually be easily collectable in digital form (e.g., via mobile phones—we are already testing this to good effect in some pilot businesses), replacing the more time-consuming, individually administered surveys we conducted in initial field experiments.

The field survey questions are in a continuous process of recalibration for the many different cultures in which we are operating, and refinement is underway to reduce their number and complexity whenever possible. The questions for human capital cover topics such as working time, work flexibility, job demands, ability to cope, workload, and support from suppliers (in the demand side piloting), customers, fellow program members, and materials and equipment, in addition to income, savings, health care, and housing. Our social capital questions cover topics like affiliation to groups, sources of exclusion, participation in collective actions, trust, norms, behaviors, and attitudes. For natural capital, we focus both on the quantitative (material input per unit of service—MIPS), accounting for all inputs from nature through five metrics (abiotic/biotic materials, air, water use, topsoil erosion) and the qualitative (hot spot analysis), which involves literature reviews, case studies, and input from domain experts. And for shared financial capital, we created what is still a rudimentary (work in progress) “shared value” index that is similar in some ways to the Gini index throughout the value chains we examined in our pilots. Gini measures income distribution in a given country using a number based on individual net income and is used to help explain income disparity. Our shared value index assesses value sharing and identifies hot spots for potential business interventions, develops comparisons across value chains over time, and maps value chains as a framework for further assessment.

The management practices that deliver mutual benefits to multiple stakeholders were calibrated to establish how they developed human, social, and natural capital—with the assumption (later tested through field experiments) that developments in these areas would necessarily have an effect on financial capital. A few examples of mutuality-related management practices we have been testing in live business pilots include a hybrid value system approach (a management concept initially put forward as “Hybrid Value Chain” by Ashoka, a prominent social business network) that consists of partnering with nontraditional (for business) entities, such as NGOs, micro-finance lenders, international organizations, and even religious organizations, to leverage their substantial social capital within communities where our business does not operate and has little if any such social capital to use as a market entry point.

Partnering in an HVS essentially is a more mutually beneficial substitute for what would in a more traditional route-to-market initiative be a “cash and carry” type of arrangement whereby the initiating business contracts with distributors to deliver its product to the market for a negotiated fee. An HVS often involves solving the problem of an NGO, a local association, or a local religious organization—for example, in exchange for something like access to the community trust the NGO, the association, or the religious organization has (credibility) that the business cannot just purchase. The NGO in this example might have as its raison d’etre finding meaningful employment for unemployed single mothers in a slum area (a real example), or a religious organization may have among its members a bevy of young, unemployed potential entrepreneurs whom they mentor but who lack the kind of good employment opportunities that the initiating company can bring. An HVS is essentially about mutually beneficial arrangements that are more often than not about far more than exchange of money. As a first step in constructing an HVS, we conduct what we call a business ecosystem mapping exercise, whereby we examine all the likely stakeholders and evaluate their needs to identify the pain points that we can then devise a means to address.

Finding ways to address the needs of the others in the hybrid value system was a means by which we could overcome traditional barriers to entry. Moreover, we are using the local entrepreneur in a new route-to-market type of initiative as the programmatic entry point, rather than something like a product, a sales or profit target, or a philosophical objective such as nutrition, even if nutrition could still be one’s desired outcome, as one example. By first empowering the local entrepreneur by ensuring he or she has what they need to be successful, especially the freedom to operate seamlessly within their unique marketplace and culture, we have learned that one may have to go outside the playbook of what business traditionally provides to its value chain stakeholders. This could mean providing an environment conducive to entrepreneurship, such as allowing competitor products to be sold by the entrepreneurs alongside one’s own, or being proactive in connecting the entrepreneurs with local relevant players (e.g., microfinance institutions). When we provide these sorts of benefits or flexibility, we are finding that the likelihood of our programs being self-sustaining and scalable is far greater because we are freeing the entrepreneur to be entrepreneurial. If we were instead to relegate the needs of the entrepreneur to a lower tier of importance, as is the case in so many CSR-type social business initiatives we have looked at, we begin to understand why the vast majority of such social businesses fail to earn enough profit to scale up, even if some provide useful benefits for company reputation.

These are just a few examples of many such management practices we are inventing, harvesting from others, and testing in the field. These will grow in number and application over time and through partnerships with other businesses and different types of entities into a second-to-none repository of data and knowledge for enacting a new, more holistic and complete form of capitalism that delivers greater value to all stakeholders. This approach is providing, for the first time, a method of systematically measuring the effects of performance and of management practices across all forms of capital—and in the process is broadening the meaning of the word “capital” itself. The following chapters lay out our approach in more detail for each of these areas of capital, along with case study evidence to support our arguments.