Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

DEI Deconstructed

Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing It Right

Lily Zheng (Author) | Andrew Joseph Perez (Narrated by)

Publication date: 11/08/2022

The importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace cannot be understated. But when half-baked and under-developed strategies are implemented, they often do more harm than good, leading the very constituents they aim to support to dismiss DEI entirely.

DEI Deconstructed analyzes how current methods and best practices leave marginalized people feeling frustrated and unconvinced of their leaders' sincerity, and offers a roadmap that bridges the neatness of theory with the messiness of practice. Through embracing a pragmatic DEI approach drawing from cutting-edge research on organizational change, evidence-based practices, and incisive insights from a DEI strategist with experience working from the top-down and bottom-up alike, stakeholders at every level of an organization can become effective DEI changemakers. Nothing less than this is required to scale DEI from interpersonal teeth-pulling to true systemic change.

By utilizing an outcome-oriented understanding of DEI, along with a comprehensive foundation of actionable techniques, this no-nonsense guide will lay out the path for anyone with any background to becoming a more effective DEI practitioner, ally, and leader.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

The importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace cannot be understated. But when half-baked and under-developed strategies are implemented, they often do more harm than good, leading the very constituents they aim to support to dismiss DEI entirely.

DEI Deconstructed analyzes how current methods and best practices leave marginalized people feeling frustrated and unconvinced of their leaders' sincerity, and offers a roadmap that bridges the neatness of theory with the messiness of practice. Through embracing a pragmatic DEI approach drawing from cutting-edge research on organizational change, evidence-based practices, and incisive insights from a DEI strategist with experience working from the top-down and bottom-up alike, stakeholders at every level of an organization can become effective DEI changemakers. Nothing less than this is required to scale DEI from interpersonal teeth-pulling to true systemic change.

By utilizing an outcome-oriented understanding of DEI, along with a comprehensive foundation of actionable techniques, this no-nonsense guide will lay out the path for anyone with any background to becoming a more effective DEI practitioner, ally, and leader.

ONE

ONE

Intentions Aren’t Enough

“So then I told him, ‘intent isn’t impact,’ and it totally blew his mind! I bet he had never thought before that the effort he was putting in trying to do the right thing might be causing harm.” The DEI practitioner grinned as she shared the story with me, and I nodded along. I had heard and told some version of this story many times, but there was always a nagging question following it. So I asked it.

“What about your own work, then?”

She looked at me, slightly put off. “My own work? I facilitate hard conversations to help people recognize their unconscious biases and become allies to marginalized communities. Are you suggesting that it doesn’t work?”

“I guess I am, yeah,” I said hesitantly. “How do you know that people actually change? How do you know that they even recognize their own biases at all . . . or that even if they do, that they then follow-up with changed behavior?”

She looked at me, and neither of us said anything.

There was more I wanted to ask.

How do we know that, when people tell us they “enjoyed the session,” this means our interventions did what we wanted them to do? Even if they say we changed their mind, how would we know if that were true?

How do we decide which interventions to apply during the session, and how do we know if they work? If they do, how do we know if positive impact sticks around after even a day?

Do we track the impact of our work over time? Do we even have a way to measure impact? Do we have a way to reach the marginalized communities we interact with for accountability? Do we ever see them again after the single session we do?

The other practitioner flashed a conciliatory smile. “I know in my heart that what I do works. And other people do, too. Isn’t that enough?”

I forced a smile in return and nodded. I didn’t agree.

Everything about how I approached diversity, equity, and inclusion changed in 2016 when I first read an article in the Harvard Business Review (it’s not every day I mark a period of my life with a business article but still, bear with me). The article? “Why Diversity Programs Fail,” by Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev. Both sociologists argue that companies’ command-and-control deployment of diversity programs, hiring tests, and grievance processes have failed to move the needle on the representation of women and non-White racial groups in the US. Their data are hard to argue with.

“Among all US companies with 100 or more employees,” Dobbin and Kalev write, “the proportion of black men in management increased just slightly—from 3% to 3.3%—from 1985 to 2014. White women saw bigger gains from 1985 to 2000—rising from 22% to 29% of managers— but their numbers haven’t budged since then.”1

And the real kicker: when DEI programs were implemented, at least in the five years of data the authors collected, the representation of most groups outside of White men decreased afterward.

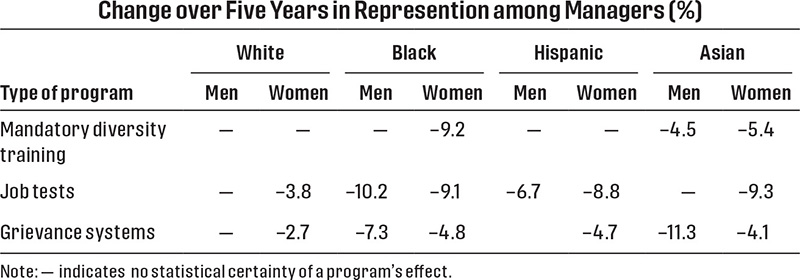

Why? Dobbin and Kalev identify a few interesting mechanisms: backlash effects, where individuals told to act a certain way respond by decisively doing the opposite, and selective standards, where raters ignore quantitative scores on job tests for friends and those they like while strictly applying score cutoffs for all other candidates. The general point that Dobbin and Kalev make is that when DEI interventions attempt to compel or control the behavior of people in power, these people often respond with counterproductive behavior that jeopardizes the outcomes the interventions are trying to create, resulting in the unintended effects shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Representation for Black, Hispanic, and Asian managers drops in the five years following the implementation of some of the most popular DEI initiatives.

Source: “Why Diversity Programs Fail,” by Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev, July–August 2016. Authors’ study of 829 midsize and large US firms.

When I first read this article, it felt like the floor had fallen from under me. I offered diversity training—and had up until that point been a big advocate for making them mandatory. I was similarly an advocate for mandating job tests, grievance systems, scrubbing identifying information from resumes, and other DEI interventions that seemed uncontroversial and widely popular “best practices.”

For the first time, I had to ask myself: How can I be sure that the work I’m doing is achieving what I think it is? And then, the inevitable follow-ups: How many practitioners are doing work that might be ineffective or even do more harm than good?” “How many don’t know and don’t care enough to find out?

For years, I sought out answers to these questions, and what I saw indicated that dubiously effective or even blatantly harmful practices were entrenched into widespread understandings of what “the work” looked like—including my own. As I’ll explore shortly, the “gold standard” of DEI work and interventions was too often just fool’s gold: shiny, exciting, but ultimately disappointing and of little value. I’ll share why this is the case and how to identify these “fool’s gold standards” so we can build an understanding of how those of us intent on effective work can do better.

(Fool’s) Gold Standards

When people think of “DEI work,” a few different focus areas consistently appear. These include DEI policies, training/workshops, surveys, talks, and volunteerism. This is because these arenas of DEI work are some of the most common ones defined by DEI professionals and are often lifted as “gold standards” or examples of “successful work” by advocates. Here’s the thing: DEI work poorly executed in any of these focus areas can turn even a substantial investment of time, resources, and effort into a zero-impact or even negative-impact outcome.

DEI Policies

Diversity policies are typically high-visibility statements that establish an organization’s intentions on DEI. They span a wide range of forms, from generic policies embodying an organization’s commitment to DEI2 to more specific policies governing hiring, training, or diversity goals. DEI policies are typically trumpeted as relatively low-effort best practices for organizations, but they aren’t perceived the same way by different demographic groups within organizations, and even the same policy framed in different ways can garner more or less support from different groups.3 For example, when considering a generic diversity policy, the gap between levels of Black employee versus White employee support can be as large as 30%. Regardless of support, how effective are the policies once implemented? Here’s the kicker—in organizations with diversity policies, members of advantaged groups are far less likely to perceive discrimination against disadvantaged groups, regardless of the actual level of discrimination. 4 When these policies are deployed in isolation as uncomplicated “fix-alls” with no additional accountability mechanisms, especially if they are perceived as passive HR policies rather than commitments that require active effort from leadership to achieve, they have the potential to simply obscure the inequity of the status quo rather than improve it. It’s quite possible (and even common) for even the most well-written DEI policy created by expert DEI practitioners to do more harm than good when deployed on its own.

DEI Training

The bread and butter of the DEI industry, “DEI training,” varies enormously in content and approach. “Courageous Conversations” (also known as “Brave Spaces” or “dialogues on [topic]”) aim to engage people in conversation about tough issues of identity and inequity. “Sensitivity Training” aims to introduce participants to inclusive language and behaviors and prescribe “do’s and don’ts” for various marginalized social groups like women, Black people, disabled people, older people, LGBTQ+ people, and more. “Allyship Training” aims to activate individuals with socially advantaged identities to play an active role in supporting their colleagues with socially disadvantaged identities. “Unconscious Bias Training” aims to help participants unpack their biases about social groups, especially biases that they aren’t aware they have (hence, unconscious), and use that awareness to act more inclusively toward others.

All of these varieties of training have their challenges, if not in their fundamental assumptions about creating impact, then in their haphazard and inconsistent deployment. Many kinds of DEI training promise lasting attitude and behavioral changes from relatively simplistic exercises and reflections, for example, but pull their exercises from sources ranging from social psychology research and grassroots organizing work to self-help guides or simply a practitioner’s own imagination.

Content aside, the logistical deployment of DEI training is often one-time and too short in length to create any sort of lasting impact: for example, many iterations of allyship training aim to increase bystander intervention,5 but effective bystander intervention training often takes five hours or more,6 while allyship training can often be even as short as an hour.

Done wrong, training can do more harm than good. Poorly executed training can reduce complex issues spanning centuries of conflict into reductive lists of “good” and “bad” behaviors; foster resentment among participants who are blamed for causing harm they don’t understand; lack safeguards to prevent conversations from becoming emotionally distressing, verbally abusive, or highly triggering for one or more parties; force individuals to self-disclose personal identities they aren’t ready to share; or push them to take on educator roles, and create an inflated sense of efficacy in participants to create organizational change.

I’ve seen these outcomes myself, whether from the perspective of a workshop participant or in helping organizations do damage control after another practitioner’s clumsily executed training.

One participant of a training that focused on inclusive language for LGBTQ+ communities later told a colleague that “transsexual” was outdated and un-inclusive language. Their colleague, who had happily identified as transsexual for years, was less than thrilled to hear that her own identity was somehow “un-inclusive” from someone who wasn’t trans themself.

One training devolved into name-calling and profoundly unproductive conflict when one workshop participant called another a “White supremacist bigot” to his face, that participant told the first participant that they would “burn in hell” for being LGBTQ+, and the facilitator did nothing as the session erupted into chaos.

One training found itself only attended by employees with no power to actually put into action anything they learned, who later reported in a follow-up survey that since the fundamental systemic barrier preventing them from using the skills they learned hadn’t budged, neither had their inaction.

Is every kind of DEI training likely to create these unintended outcomes? No, but at present, there are few safeguards in the industry to prevent them. Few practitioners collect impact metrics on the outcomes of their training, and few organizations do so on their side, either. Longitudinal impacts are virtually never tracked. Practitioners come into the field with experience ranging from full-on PhDs in intergroup conflict resolution to having read one or two books about race or gender in their spare time. Organizations that don’t recognize this might bring someone in to deliver an unconscious bias training expecting a professional familiar with the research and its nuances in execution, only to get someone reading out instructions on an exercise that attendees could look up online and participate in on their own. Unless the lack of quality control and consistency within the field changes soon, hastily deploying a DEI practitioner to deliver training, even a practitioner with a “good reputation,” will continue to mean taking a gamble with organizational outcomes and employee well-being on the line.

DEI Surveys

DEI surveys collect employee self-reported data on metrics like fairness, belonging, engagement, and well-being, then disaggregate it by demographics like race, gender, sexuality, age, and more to uncover disparities and inequities in outcomes. The promise of DEI surveying is that armed with good data, organizations can direct their efforts toward programs and interventions that are most likely to succeed. The challenge with DEI surveys is that “good data” is much easier said than gathered. International variation on the legal collection of sensitive demographic data notwithstanding,7 DEI surveys often involve a large degree of vulnerability from respondents and sensitivity on the part of employers and/or third parties engaging in data collection. There are numerous failure modes that arise when the respondent vulnerability is lacking or survey administrators lack the appropriate sensitivity: low response rates caused by a low level of respondent trust can jeopardize quantitative data; high levels of hostility and distrust among employees can lead to survey reporting being used as a vehicle for organizational politics or interpersonal agendas; mishandling of sensitive employee data can fuel illegal retaliation and discrimination; failure to handle small-n problems8 when only a small number of employees of a certain disadvantaged identity (e.g., “gay”) exist can compromise anonymity. In addition to challenges ensuring that identified disparities reflect real disparities and not simply a researcher’s own predispositions,9 DEI surveys create the expectation that collected data will be used to address identified issues as expeditiously as possible. If data transparency is lacking or company leadership is unwilling to act on all the findings from the data, this can substantially erode trust and demoralize a workforce.

Even when designed with all of these concerns in mind, DEI surveys have fundamental weaknesses: a single survey only measures reality at one point in time and cannot be used to prove causation, that one action causes another. Even if two outcomes appear to be linked—for example, a department with more diversity has greater productivity than a department with less diversity—there can be any number of other explanations for the correlation and substantial risk associated with hastily concluding that adding diversity to another department will thus increase its productivity.

DEI surveys are only as good as the practitioner or expert administering them and the organizational leaders following up (or not) on their findings. Ineffective deployments of DEI surveys can result in unintended consequences, including retaliation, decreased employee trust in leadership, and unhelpful interventions informed by inaccurate survey conclusions.

DEI Talks

One of the most commonly used ways to bring DEI-related content into an organization, DEI-related talks, lectures, keynotes, and other speaking engagements typically involve one or more speakers and advocates addressing an internal audience of employees on any number of DEI topics. Pick any DEI concept you can think of and look it up—there’s likely a DEI talk about it somewhere on the internet. As an intervention, DEI talks are typically used as organizations’ go-to way to demonstrate their commitment to DEI through a high-visibility engagement and introduce attendees to “new” DEI-related content and ideas. While they are indeed effective for raising the visibility of issues or topics and increasing momentum for new or existing initiatives, DEI talks themselves have little ability to create long-term behavior or organizational changes. For example, while a DEI talk exhorting the value of flexible working arrangements on mental health may be inspirational, unless employers actively follow up by enabling greater flexibility, through policy and practice, mental health won’t actually change. Unfortunately, employers rarely follow up on DEI talks—and recycling talk footage for external-facing marketing doesn’t count.

This doesn’t stop employers from requesting DEI talks, however, and investing sizable budgets into getting celebrity speakers onto their stages. But when budgets for genuinely impactful DEI work are a tenth or hundredth of speaker budgets, this can often result in frustration, growing impatience among a workforce, and a perception that DEI efforts are “performative” and intended only for show rather than impact.

DEI Volunteerism

The final category of common DEI work is volunteerism, where DEI work is undertaken by passionate employee volunteers, typically organized into informal or formal workplace groups. The structure of these groups can vary: employee resource groups (ERGs) are usually organized around one particular identity or affinity (e.g., Black, woman, LGBTQ+, disability), while councils, working groups, and committees are formed to address DEI issues more broadly. DEI volunteer groups, specifically ERGs, have a long and storied history: the first was founded in 1970 by Black employees at Xerox as a forum to discuss shared experiences and advocate for racial equity and became the template for ERGs to this day.10 In the fifty years since their inception, however, ERGs were slowly repurposed to increasingly center organizational goals rather than community ones. Today’s ERGs and other volunteer groups are often proudly described by organizations as helping solve key business challenges, develop DEI strategy, and consult on complex topics of identity and inequity at work.

This is a problem because employee-led groups often lack the authority to make real decisions and the resources to act effectively. They may be able to advocate for changes like creating hiring rubrics or conducting a DEI survey but must rely on the goodwill of actual decision-makers to act on their recommendations. In other cases, these groups can be tasked with not only advocating for DEI, but carrying out the organization’s DEI work in its entirety. They might be asked to gauge employee sentiment, analyze survey data, develop a DEI strategy, and coordinate organizational change themselves. This is an enormous risk for several reasons. One, the magnitude of this work almost always burns out employees who engage in it but receive no additional support, resources, or recognition for doing so. Two, the lack of experience or expertise among these employee volunteers often results in poor DEI decision-making with the high potential to do more harm than good—if your corporate office had a sitewide plumbing issue, would you solicit passionate employee volunteers who had fixed an occasional plumbing issue in their houses to fix it? Third, the lack of resources these groups are allocated cheapens DEI work for everyone. I’ve been approached by more apologetic ERGs than I can count, asking me to perform an organization-wide assessment and analysis for scraps because no other department in the organization was willing to take that work on. In one case, an ERG desperately offered me $600 to do at least fifty hours of work—a generous use of 75% of their entire yearly operating budget.

There’s nothing wrong with DEI volunteerism as a way to augment effective efforts. But when scope-crept DEI volunteerism is used as a replacement for well-resourced DEI work undertaken by trained professionals, it can become a way to exploit passionate employees for their labor, avoid accountability, and perpetuate a glacial pace of change.

Am I trying to say with all this that “DEI doesn’t work”? No—something quite different. I’m saying that DEI done wrong doesn’t work, and DEI that doesn’t work is often the case because it was done wrong.

DEI policies aren’t inherently bad. Neither are trainings, surveys, talks, or volunteer efforts. But they aren’t inherently effective just by virtue of existing, and this is where many well-intentioned practitioners and advocates trip up. Every practitioner I know has a heartfelt story about a workshop participant whose mind was changed on an important issue or who tearfully shared a reflection about how they had never realized their own privilege or committed publicly to be a better ally. But we don’t just evaluate salespeople on how compelling their stories about eager customers are. We don’t just assess web designers on how inspired we feel hearing them talk about coding.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion work in organizations is about achieving diversity, equity, and inclusion as tangible outcomes at a scale beyond the individual. This is true whether we are consultants, practitioners, workplace leaders, employee volunteers, or anyone else who wants to do DEI. Given the state of the working world, we don’t have the luxury of centering our own feel-good narratives about change over actual results. Either we know that our work is effective and can prove it, or we don’t and need to find out.

Inequitable, Exclusive, Homogenous

In Silicon Valley, following widespread calls for tech companies to release data on the diversity of their workforce in the mid-2010s, the number of Black and Latine (pronounced “lah-ti-neh”) workers actually dropped.11 Meta-analyses show that, in US labor markets, hiring discrimination against Black workers hasn’t changed since 1989 and declined only slightly12 for Latine workers. Employment discrimination charges filed under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) have held constant over time;13 a good 70% of physicians don’t even know how to meet their legal requirements to treat people with disabilities.14 While American women’s educational attainment has surpassed that of men, their labor force representation, pay, and leadership representation in businesses and government remain lower than that of men, with gains having stagnated for decades.15 This list is endless: discrimination is alive and well in the US against Native Americans,16 the LGBTQ+ community,17 pregnant people,18 people experiencing poverty,19 and many more social groups and dimensions than just these.

While the exact dimensions of identity and social status affected by discrimination and inequity differ across the world, discrimination in the workplace is a global phenomenon.

A meta-analysis identified racial discrimination in Belgium, Canada, France, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden—with the worst racial discrimination documented in Sweden and France.20 While data is sparser in some regions,21 workplace discrimination and inequity are also documented across east Asia22 , 23 south-east Asia,24 sub-Saharan Africa,25 and West Asia and North Africa (WANA),26 with far more data existing than makes sense to share here.

More tangible examples closer to home? Take the #MeToo movement started in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke, which went viral in 2017 following widespread sexual abuse allegations against former film producer Harvey Weinstein.27 A movement driven by social media on every continent, spanning tens of millions of tweets and thousands of articles, #MeToo prominently brought issues of sexual assault, harassment, and discrimination to the forefront.28

Now, five years later, the effects of the movement are starting to materialize. The #MeToo movement undeniably increased reporting of sexual assault and harassment by empowering victims to share their stories—with a smaller but notable increase in arrests, as well.29 But belief in the benefits of the movement is polarizing, with only 25% of men in a US study believing that recent attention to sexual misconduct had a positive impact, versus 61% of women.30 This split is far from the only concerning effect. Within workplaces, following the #MeToo movement, a 2019 study found that 60% of managers who are men felt uncomfortable mentoring, working alone with, or socializing with women—a 32% jump in discomfort from just the year prior, with 36% reporting that this discomfort stems from worries that engaging in any way would be seen poorly.31 This trend is exacerbated in senior-level men, who are now 12 times more likely to hesitate to have 1-on-1 meetings with junior-level women than before.

At the same time, while more blatant sexual harassment like sexual coercion and unwanted sexual attention decreased in the period between 2016 and 2018, at the height of the movement, gender-related harassment increased. 32 The #MeToo backlash, as this trend became known, continued to worsen in 2019—men’s fears around unfair accusations and women’s concerns that men would simply continue harassing more discreetly only increased, with disastrous impacts on men’s desire to interact with women in hiring, mentoring, or traveling.33 As the movement spread outside the US, its impact diverged in ways we continue to study. China’s fledgling movement is facing a crackdown;34 France’s movement faced enormous backlash in the late 2010s but may be gaining greater support now;35 Latin American movements across Mexico, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina focused on femicide, or the murder of women;36 Japan’s movement never quite took off.37 And the #MeToo movement is only one facet of the ongoing work to achieve gender parity and gender equity worldwide—an end state that, according to the World Economic Forum, was nearly 100 years away from becoming a reality after 2020 and 135.6 years away after 2021 when the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were taken into account.38

This is just one example, but the lessons we should take away from it should be sobering. As societies and as a world, we are far from where we need to be, and our efforts to do good may result in unpredictable consequences—and harm—we are unprepared to handle.

Even if we do DEI work each and every day, it’s wishful thinking to believe that the trajectory of the world will take us automatically toward equity and that all we have to do is ride the current to get there eventually. There is no such thing. If we achieve DEI, it is because all of us have put in the thoughtful, intentional effort to do our best and do things right. Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum says it well when she uses the metaphor of a moving airport walkway, or a conveyor belt, to describe racism; I believe the metaphor applies effectively to other systemic inequities, too.

“Active racist behavior is equivalent to walking fast on the conveyor belt. The person engaged in active racist behavior has identified with the ideology of White supremacy and is moving with it. Passive racist behavior is equivalent to standing still on the walkway. No overt effort is being made, but the conveyor belt moves the bystanders along to the same destination as those who are actively walking. Some of the bystanders may feel the motion of the conveyor belt, see the active racists ahead of them, and choose to turn around, unwilling to go in the same destination as the White supremacists. But unless they are walking actively in the opposite direction faster than the conveyor belt—unless they are actively antiracist—they will find themselves carried along with the others.”39

Every time I think of this analogy, I’m struck by the final line. One part of it, in particular: “a speed faster than the conveyor belt.” Too many of us assume that simply turning around to move against the flow of injustice already makes us effective antiracists, effective advocates for women, LGBTQ+ people, disabled people, and so on. But as this metaphor powerfully illustrates, regardless of your intentions, there is a certain—perhaps even objective—amount of progress you must achieve to say that you are making and have made a difference.

Move too slowly? You’ll be facing the right direction, but an onlooker will still see you going the wrong way. You’ll be earnestly, vigorously, and even haughtily moonwalking toward inequity.

An uncomfortable percentage of modern DEI work amounts to moonwalking toward inequity, from poorly designed training to irresponsibly deployed policy to earnest but unskilled volunteer initiatives.

“But Lily, our leaders have their hearts in the right place”—it’s their actions and impacts that matter more.

“But Lily, our company has a racial justice commitment”—racial justice outcomes are more important than statements of commitment.

“But Lily, at least our company is an industry leader on issues of disability”—being the least inaccessible or inequitable isn’t the same as achieving accessibility and equity.

I want you, myself, and everyone else to read this and sit with the discomfort:

Our organizations, and certainly our world, continue to be unacceptably inequitable, exclusive, and homogenous. And despite the best of intentions, we as leaders, advocates, activists, and practitioners don’t yet have a collective handle on how to meaningfully change that at scale.

The DEI-Industrial Complex

It’s one thing to say that, as a collective, the DEI industry doesn’t have a handle on how to ensure effectiveness and quality control as a standard. That’s not a problem on its own—many emerging industries and fields experience similar challenges. The problem is that if you look up “DEI” or “diversity equity and inclusion” on any internet search, that’s the last impression you would get of what you’d find.

Endless articles on terms and definitions. Think pieces, webinars, and infographics galore. Then, the sponsored ads—for consulting firms, executive coaching, online courses, training and workshops, and every other DEI service under the sun. If I didn’t know better, I’d say that far from a fledgling industry figuring itself out, DEI was a well-oiled machine that brought profits to the people driving it without being accountable for the lofty goals it preaches.

This critique of the industry is increasingly common. More and more, critics are asking if the DEI industry does more harm than good40 and going so far as to call the relationship between DEI and the corporate world the “DEI-Industrial Complex”41 —arguing that the nearly $10 billion-dollar42 and growing DEI industry enables the inequitable status quo and corporate misconduct to continue existing.43 They make the case that the DEI industry is in the process of being (if it hasn’t been already) co-opted by corporate leaders who want the reputational benefits of having “engaged in diversity, equity, and inclusion work” without needing to fundamentally make any real change. And DEI professionals are either intentionally or unwittingly enabling those intentions by doing work that doesn’t work, dressed up in inspiring language like “antiracism” and “social justice.”

This critique frames DEI practitioners and corporate leaders in a mutually beneficial, symbiotic relationship. Companies get their inspirational talk or training or initiative, reputational boost, and a few more months of their employees’ patience. DEI practitioners get money in their pockets. But employees dealing with microaggressions find the source of their problems unchanged when the good feelings from the DEI talk wear off. Employees being retaliated against by their managers don’t see any lasting changes in behavior after the mandatory workshop. Employees seeing no future for themselves in the all-White, all-male senior leadership at their company are no more hopeful than they were following the expensive “antiracist exercise” at the leadership retreat. Candidates facing hiring discrimination are no closer to getting jobs after the shiny nondiscrimination statement was lauded on social media.

To be clear, some organizations take their DEI budgets seriously and rigorously screen the practitioners they bring in. But even then, these efforts can miss the mark. I’ve seen some organizations request that the workshop practitioners who will train a small fraction of their workforce have ten years of experience delivering training that was only developed five years ago while booking a speaker to address their entire workforce on the sole basis that the head of HR liked hearing that speaker five years earlier. I’ve seen some organizations request “data-driven” DEI practitioners able to put bleeding-edge research never applied in the field into practice but who somehow already have a “measurable track record” of using those same practices.

And the vast majority of organizations don’t even do this. They hire the cheapest practitioner they can find, pay to record one 90-minute training, and subject their entire workforce to the recording as a one-size-fits-all mandatory “training.” They hire inspirational speakers who lack skills in interpersonal facilitation and conflict resolution to facilitate their “hard conversations” that predictably go wildly off the rails, then conclude from the experience that “DEI isn’t worth engaging in.” It’s infuriating.

In the face of this, I don’t blame many people, including even former DEI advocates, for becoming skeptical of DEI work. Real progress is stagnating while the industry’s profile skyrockets, with the intended beneficiaries of this work being exposed all the while to DEI interventions that are lackluster, ineffective, outdated, or just plain offensive.

Recently, for example, a colleague with no previous exposure to corporate DEI shared with me a story of sitting through a mandatory DEI training, led by a person who was not White, in which the facilitator referred to different racial groups as “Negroids, Caucasoids, and Mongoloids” before listing a long list of racial stereotypes to the unwitting audience. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing—a racial classification system developed in the 1780s still deployed in 2021. The training deeply confused and upset the audience. “What is wrong with DEI practitioners?” demanded my colleague afterward, and all I could do was shake my head and apologize on behalf of a person I had never met. What is wrong with DEI practitioners?

Maybe it’s the complete lack of standardization or quality control in our industry. Maybe it’s the fact that there are zero qualifications required to enter the industry and that while some practitioners enter with industrial-organizational psychology, education, human resources, learning & development, grassroots organizing, or organizational development backgrounds, others enter with nothing but “passion and lived experience as a minority social group.” Maybe it’s the fact that there are no ways to distinguish effective certification programs from the ones peddling fluff and that even the best programs lack a unified approach to what it requires or even what it means to do the work.

Critics point to these factors as reasons why the DEI industry does more harm than good, and some go so far as to claim it is past saving, suggesting that those who care would be better off disengaging from it completely. The most idealistic advocates brush off these factors as slight complications alongside an otherwise unproblematic and hopeful upward trajectory. Both have a point, but both mischaracterize the path ahead of us.

Hope for a better future is important. We need to see the DEI industry and DEI work in general as an endlessly improving discipline with room to grow that has meaningfully achieved change. Much of this progress was not achieved in isolation but instead in collaboration with and supporting social movements, activists, and advocates who unapologetically work toward a better world. At the same time, our actions have consequences, and we bear an enormous responsibility toward all marginalized groups to ensure our work moves the needle in the right direction and mitigates unforeseen negative consequences.

Accountability is important. We need to see the development of mechanisms and means for people anywhere and everywhere to hold DEI work accountable in the same way DEI work aims to hold organizations accountable. For accountability, the industry needs transparency, structure, and community so that anyone can understand the work being done, how and why leaders and practitioners know what they do, and to what extent any of it is creating changed outcomes—with consequences for work that consistently solicits the trust and patience of marginalized communities without delivering meaningful change in return. At the same time, transforming the current state of DEI work won’t happen immediately, and we need to stay focused on the end goal without demanding perfection from every step required to get there.

This, in my opinion, is the next evolution of DEI work beyond simply “good intentions.” It is DEI without the bells and whistles, boiled down to what is pragmatic, rigorous, and effective for solving challenges, changing outcomes, and achieving the impacts we need to.

I won’t dress it up any more than that—I have no intention of selling “pragmatic DEI” as an exciting new thing to spice up your DEI work. To me, the explosive and growing interest in this industry and this work is nothing less than an existential threat. Either we all figure out how to do DEI and do it right, or this work implodes under the weight of its popularity and everyone doing it becomes irrevocably complicit in the inequitable status quo.

We DEI practitioners like to say that “intentions do not equal impact.” It’s time for us to face the music—that saying applies to us, as well. I have no interest in reading an article in a few years titled, “Your Company Started Talking About DEI. Here’s How to Quit.” If you don’t either, then we have to collectively get our act together and do this work right.

TAKEAWAYS

• DEI at present doesn’t create the impact it promises. Despite the long history of what many now call diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) (and many other related acronyms), much of this work has been demonstrated to have only a limited impact, not commensurate with the enormous financial investment in the industry.

• DEI work is unaccountable and inconsistent. While a wide range of work exists under the DEI umbrella, a lack of quality control, support, and accountability among the practitioners and advocates who undertake that work means that impacts can be inconsistent or nonexistent at best and actively harmful at worst.

• Good intentions haven’t moved the needle at scale. Many change-making efforts in society are driven by positive intentions and result in high-visibility movements aimed at creating lasting change. However, inequity continues to be the status quo across the world, and important outcomes like rates of workplace discrimination have stayed persistently constant even as awareness and efforts to make change have increased.

• Trust in DEI is tenuous as skepticism grows. As change fails to materialize while the DEI industry becomes ever-more lucrative and high profile, critics increasingly speak of a DEI-Industrial Complex: an informal partnership between the DEI industry and organizations in which money flows but the status quo remains unchanged or even strengthened.

• We can do better. Pragmatically doing DEI work requires tempering hope for a better future with the accountability to take ownership for impacts in the present. By centering outcomes and focusing on gaining greater understanding and efficacy to make a change, we can collectively challenge the DEI-Industrial Complex by doing DEI right.

EXERCISES AND REFLECTIONS

1. How does your organization address DEI? Name as many initiatives, interventions, or commitments as you can (you can look them up if needed). How effective have these been in achieving what they were intended for? How do you know?

2. Write down a list of three DEI practices you’ve heard of before— any three. Then, imagine hearing that a DEI practitioner has been hired to implement each practice. Next to each practice on your list, write a number from one to five to describe your reaction to this news, with five being “extremely hopeful” and one being “not hopeful at all.” Reflect on your responses. Why did you answer the way you did?

3. Name a DEI practice or intervention that you trust highly—you believe that it’s likely to result in positive outcomes when deployed. Then, name a DEI practice or intervention that you distrust highly—you’re skeptical that it’s likely to result in positive outcomes when deployed. Why did you categorize those two practices or interventions the way you did?