CHAPTER ONE

Finding Your Role as an Inclusive Leader

Every society has its protectors of status quo and its fraternities of the indifferent who are notorious for sleeping through revolutions. Today, our very survival depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

Over the past several decades, companies have invested heavily in DEI programs and initiatives. Yet most programs that exist today are still focused on compliance and performative actions, are siloed in HR departments, and lack the commitment and involvement of senior leaders. Few are designed to shift systems or address the patterns of exclusion, oppression, and disadvantage underrepresented and marginalized groups continue to face in the workplace.

To build a more inclusive and equitable future, leaders in positions of power and influence must play an active role in disrupting the status quo. The hard truth is that, with a labor market that’s becoming more competitive and more diverse, leaders who aren’t making an effort to become more inclusive, accountable, and equity minded will be left behind. Yet I have found that most leaders are still holding back.

In my twenty years of DEI work, I often encounter three types of leaders. I have worked with some leaders who really get it, who grasp the extent to which the playing field is not equal, and who understand that they have a role in fixing that. They lead with purpose and are on the front lines of challenging inequities and changing systems. When we work with leaders like this, we can dig in and get right to work.

Then there are other leaders who have awakened to the realities of the world around them but are reluctant to get involved. Many don’t do anything because they’re afraid of making a mistake, of getting it wrong. This is new territory, and they don’t feel like they have the right words or vocabulary to step into the conversation. They are not even sure if they are welcome. So they stay on the sidelines and their lack of action maintains and protects the status quo.

And there are still too many leaders who just don’t understand the depth and impact of the inequities that surround them. They don’t see what any of it has to do with them. With these leaders, I can’t count how many times deflections fill the room when I start to talk about DEI and why it matters. These are just a few that are verbalized:

-

• People need to stop being so sensitive.

-

• I’m buried—I don’t have time to prioritize this work.

-

• I prefer to see past race and gender—we’re all just people.

-

• We did unconscious bias training, so I don’t think we have any major issues here.

-

• Are you suggesting we should have quotas?

I think of these as deflections because they aren’t genuine curiosities about the way forward; they are barriers and distractions that are often raised to obscure or delay responsible action. But being unwilling to look clear-eyed at the dramatic changes around us—in our colleagues, in our professional landscape, in global markets—is a classic tactic of avoidance.

Don’t get me wrong—I don’t think of these types of leaders as bad people. But I do think many people who are in leadership roles probably have no idea what many of their colleagues are going through at work since the experience is likely vastly different from their own reality. And because they don’t understand the problems people with other identities experience, they aren’t able to take the brave and necessary leadership actions needed.

When the world around us looks like us and is designed to work for us, it can be hard to grasp the extent to which the playing field is skewed in our favor. For those who have more privileged backgrounds, it can be easy to dismiss or downplay the experiences and outcomes of people who’ve been historically marginalized and underrepresented in a given system. The truth is, privilege can be invisible to those of us who have it.

The reality is that biases and inequities have permeated just about every aspect of the professional world, from decades (if not centuries) of pattern build-up. This is not a problem that will just go away if we all think good thoughts or avoid facing the truth about the systems around us. As the ground rapidly shifts under our feet, our inability to see the once-in-a-generation opportunity for change is a liability for all of us. Our future impact—and legacy—depend on how we step up during this moment.

Our inability to see this once-in-a-generation opportunity for change is a liability for all of us.

The unwillingness to look at what needs to change and how we as leaders can contribute is a missed opportunity to evolve, to transform, and to equip ourselves to build something that works for more of us—and that will benefit all of us.

Unfortunately, no business strategy, including DEI, will deliver optimal results if individuals with power and influence are disconnected from that strategy. If the very people who are in the position to make change happen are unaware there’s a problem, in denial that inequities exist, or throwing their hands up about the supposed complexity—or cost—of fixing the problem, we will never scratch the surface of what’s possible.

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

I have always found this quote by MLK inspirational. In the midst of confusion, overwhelm, and uncertainty about our increasingly chaotic world, it gives me hope that an inevitable shift toward a more just world is possible, where all people are treated equitably and respectfully. But most of all, I don’t believe his words condone passivity or inaction, for any of us.

It used to be enough for me to take solace in MLK’s words, but because I’ve been focused on building more inclusive workplaces now for nearly two decades, I’ve come to realize a hard fact: just a relative few of us are doing the lion’s share of the work to bend the arc.

The pressing question this leaves us with is, who’s missing from the change team, and why?

Historically, DEI programs have been centered around the needs of marginalized and underrepresented employees and addressing the barriers and inequities these groups experience. Although unintended, the impact of this focus has distanced many people in leadership positions from understanding their potential contribution and role in DEI efforts.

For the most part, it is members of marginalized communities who take up the mantle to do the work of challenging discriminatory practices and systems. But every time we automatically turn to the woman, the Black or Brown leader, the person with a disability, or any other individual belonging to a marginalized community to take responsibility for identifying and addressing organizational inequities, we are abdicating our own role and responsibility. This needs to change.

Each of us must begin to take responsibility for the roles that we can play, especially if we hold positions of privilege, power, and influence but have been passive or inactive. We may not have been directly affected by inequities; we might feel it’s not our fight. But this in itself is a privilege: to have the choice to remain on the sidelines in the fight for equity while others struggle.

The ability and choice to remain on the sidelines is a privilege available to some—not all.

Whenever my company begins work on an organization’s DEI strategy, we recommend involving top leaders. When it comes to disrupting the status quo and creating equity in the workplace, much power lies with leaders who set the standards and tone for everything from who gets hired and who advances to what the workplace culture looks like. We understand that without their buy-in and personal involvement, our efforts will have more limited impact and will be more difficult to sustain. The reality is, leaders are an influential employee group in the workforce to drive real change.

As leaders, we can’t sit back and wait for the arc of history to bend by itself or keep expecting others to put their shoulders to the wheel. If we want a more just world, one in which the playing field begins to equalize, we need to grasp the urgency of our own role and responsibility to bend the arc. We have to do our part, and we still have a long way to go.

Finding Your Way into the Conversation

Privilege is not in and of itself bad; what matters is what we do with privilege. We have to share our resources and take direction about how to use our privilege in ways that empower those who lack it.

—AUTHOR AND ACTIVIST GLORIA JEAN WATKINS (PEN NAME BELL HOOKS)

The greatest opportunity of inclusive leadership is being able to interrogate ourselves about the role we play in the systems around us and how we can affect positive change in those systems. Yet, when it comes to addressing systemic inequities, it is almost always a lack of understanding on the part of leaders about what the issues are, what role they should play in resolving those issues, and how they get started that is holding them back.

One way to get started is to do your homework to learn more about the privilege you hold and to understand better how your privileges may contribute—even unintentionally—to discrimination, inequity, and exclusion. As you learn more about your privileges, you will come to recognize what parts of your world, your workplaces, and your communities work for you and are, indeed, optimized for you. You develop an awareness that the same system can be experienced completely differently by different people. The fundamental question about privilege is this: How much of my world was built with me in mind?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw the answers to that question play out before us. Asian communities were “othered” during the pandemic and scapegoated for the virus merely because they looked like the people from the part of the world where it was first reported. Hate crimes against the community increased significantly throughout the pandemic across the world. But the Asian American community has always experienced inequities, exclusion, violence, and dehumanization. Historically, anti-Asian racism predictably increased during times of war, economic declines, and disease. These are hard truths.

As the pandemic wore on, Black and Hispanic communities were hit the hardest. They were overrepresented in low-paying jobs that were less likely to provide health coverage or paid time off. They got sick and died at higher rates. They disproportionately held front line jobs with high levels of public contact that put them at greater risk of contracting the virus while others with more privileged identities had the opportunity to safely shelter in place. These types of disparities didn’t happen overnight in the face of a pandemic. They have always been with us and are deeply embedded in systems and structures around us.

The pandemic was also devastating for women, with caregiving demands driving millions from their jobs. Yet women were paying a price for caregiving even before the pandemic. The advancement of women has always been hampered by workplace policies that fail to support work-life balance; the pandemic merely brought into focus the disproportionate burden women carry when it comes to caregiving and the cost of that burden to their careers. Despite the overwhelming evidence and research about the impact of caregiving on women, most companies continue to fail to prioritize their needs.

As the pandemic made so very clear, we may all weather the same storm, but we are in very different boats.

Privilege is a fundamentally loaded topic, and for those of us with privileged identities, it can be difficult to talk about. In working with senior leaders over the years, I have noticed that many of them are uncomfortable with the concept of privilege, don’t know how to deploy their privileges for systems change, or are ashamed of the personal advantages that privilege offers them.

Many of us assume that by admitting our privileges, we somehow invalidate how hard we have worked. We may assume that the label privileged implies we don’t deserve to have what we have, or it infers that we have never experienced hardship. Having privilege does not mean that an individual is immune to life’s hardships. But it does mean having an unearned benefit or advantage by nature of one’s identity.

I have struggled with the concept of privilege personally. In many ways, people view me as the kind of person unlikely to experience any challenges with inequity. After all, I am White, cisgender, and able-bodied. I have other invisible privileges: I grew up in a safe home where I didn’t want for anything and where I was told I could be anything I wanted. I had access to a quality education and the opportunity to go to the college of my choice. These aspects of my identity have enabled me to function more easily in the world, more safely, with more automatic—and often unearned—protections. They are the invisible, silent tailwinds that speed me along just that much more quickly.

I have also come to understand that my privilege is about what I did not have to experience, the ways in which I don’t struggle on a daily basis—the ways in which I’m safer, more protected, more shielded from the harsh realities of bias, exclusion, and violence.

Privilege is also the way in which we didn’t—and don’t—have to struggle.

Yet, for most of my adult life, I have also identified with and led from a mindset of marginalization as a member of the LGBTQ+ community and as a woman, each of which can be detrimental in the business world. I came out when I was twenty-two and struggled to find examples of professionals who were like me in the roles I aspired to fill one day. Very few women, and even fewer openly gay professionals, seemed to be at the top. Unfortunately, this is still the case.

Anxiety about my identities in the workplace often dominated my thoughts. I had a pervasive fear that if people knew the real me, it would hurt my relationships and my reputation. So, for a long time, I hid the parts of me that I feared would be rejected. I avoided sharing personal stories. I felt like an outsider at work.

As someone with a foot in several worlds of identity-based privileges as well as identity-based disadvantages, for decades I have been on my own journey of endeavoring to feel seen, heard, and valued, while at the same time grappling with how I can use my privilege and influence to drive equity and inclusion for others.

Privilege is not an absolute. It can coexist alongside identities that leave us feeling marginalized and disadvantaged.

Rather than feeling confused, frozen, or disconnected from the fight for equity, or ashamed of my place of privilege in many systems, I realized it’s more important to understand what I can do, to learn more about the role I can play. For those of us who routinely benefit from privilege, the challenges are to acknowledge its existence, to make it visible to ourselves, and to leverage the advantages it confers.

I believe it is time to reframe the concept of privilege in a way that doesn’t cause defensiveness, or fear, or keep us frozen in place but rather feels like something we can acknowledge, own, and activate.

All too often, I’ve observed that the concept of privilege is employed to call out or otherwise criticize and dismiss the potential contributions of people with privileged identities. I believe this is holding us back. Although it is critical for people belonging to dominant groups to understand the advantages their identities confer—and how people with other identities aren’t afforded those same advantages—if we are only calling them out for being part of the problem, we are alienating them from getting involved in solving those same problems.

I’m not discouraging anyone from calling out individual harmful behaviors and microaggressions, but when we call out and dismiss entire groups of people only because of their privileged identities, we may inadvertently be distancing them from getting involved and using their power and influence for the greater good.

I encourage each of us to practice calling in behavior to invite people of all identities, including those with privileged identities, to take a seat at the table. Calling in creates the space for individuals to take responsibility, to learn more, and to do better. We will never build momentum to create meaningful change if we continue to work in isolation or as adversaries. We need to learn how to work in partnership and in solidarity.

Getting Off the Sidelines

Change will not come if we wait for some other person or if we wait for some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.

—FORMER PRESIDENT OBAMA

There is no such thing as the perfect time or the right way to do this work. The time is now, and these conversations are already underway. It’s incumbent on those of us whose identities make us insiders in a system to go first. The only choice we have is to step up and show up, however imperfectly—to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. If you aren’t pushing yourself to do more and pushing others around you to improve too, chances are, you aren’t really leading.

Being an inclusive leader starts with a spark to do better. That spark lives inside all of us, almost like a pilot light. It’s always there, ready and waiting to create a bigger flame. Inclusive leaders have that spark. They have a genuine desire to make the world a better place. They are aware of, and know how to utilize, their power and privilege to raise issues, to challenge norms and behaviors, and to root out and prioritize core issues that perpetuate exclusionary dynamics. They push themselves as much as they push others.

When you have that spark, you start to see all the opportunities to better support others unfold. You want to do more. To learn, to grow, and to contribute. To challenge the status quo and participate in creating lasting change. To fulfill your potential as a person and as a leader. To leave things better than you found them.

The hardest part about becoming an inclusive leader can be that initial work to switch the pilot light on, to become aware that you are already equipped with the ability to make a difference, and to learn how much your efforts are needed.

But to ignite that light, you must uncover your biases and learn to manage them. You must own your privileges and the advantages they have afforded you and acknowledge that it is not an equal playing field for many around you. This can be an uncomfortable and humbling journey of self-discovery that’s not always easy.

Leadership is not leadership unless it’s uncomfortable.

I deeply believe that each of us has the capacity to affect meaningful change. The question is, can you ignite your will to change?

This book lays out a step-by-step process to becoming a more inclusive leader, to finding your role and voice in affecting societal and workplace change. By deciding to read this book, you have demonstrated that you are already committed to growth, to pushing yourself, to being uncomfortable with your own limitations and inadequacies, and to opening yourself to the identities and experiences of others.

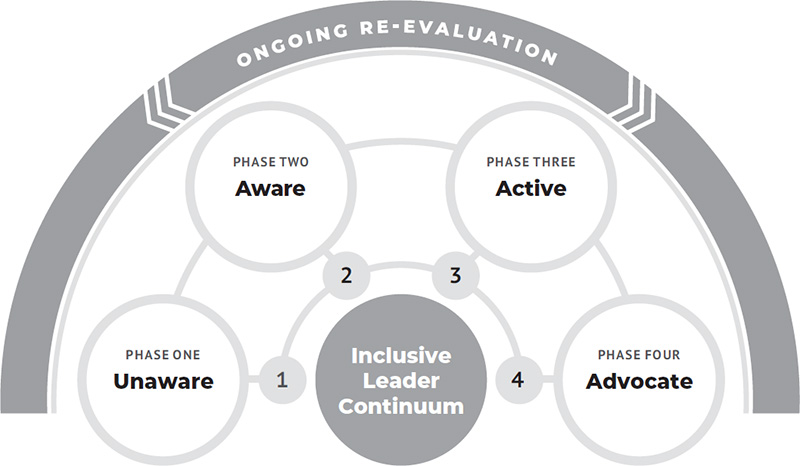

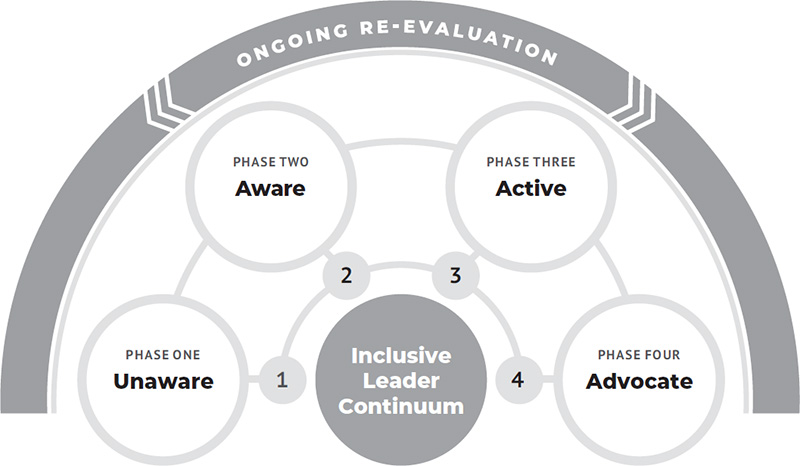

The road of inclusive leadership is a very personal one. As you dive into the four stages of the Inclusive Leader Continuum, I urge you to push yourself. To examine not only your own actions but also the ways that your inaction can create a safe space for broken systems to continue unchecked.

As leaders, our sphere of influence is bigger than we perceive, and we squander the resources we have access to every day we remain inactive and uninvolved. So, let’s get started.

Chapter Discussion Guide

What You Can Do

-

• Learn more about the concept of privilege and how it personally advantages and disadvantages you and how that may be different for other groups of people.

-

• When thinking about the privileges you hold, what emotions come up for you? Why do you think that is? Are these emotions holding you back from activating your power and influence in the change effort?

-

• If you haven’t gotten involved in your organization’s DEI efforts, reflect on what’s holding you back and start to think about what role you can play.

Conversation Starters

-

• Discuss the concept of privilege as a group, and explore how we all have identities that may advantage and disadvantage us to gain a better understanding of the unique lens with which we all view the world.

-

• Discuss as a group the different ways privilege plays out in your organization and workplace. Talk about how privilege benefits some and disadvantages others.

-

• Strategize ways the group can get more proactively involved in DEI and the change effort. Identify areas where you may need support, training, or education to approach this work in a meaningful and relevant way.