Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

Let's Stop Meeting Like This

Tools to Save Time and Get More Done

Dick Axelrod (Author) | Emily Axelrod (Author)

Publication date: 08/04/2014

Using the same principles that make video games so engaging and that transformed the numbing assembly line into the dynamic shop floor, the Axelrods outline a flexible and adaptable system used to run truly productive meetings in all kinds of organizations—meetings where people create concrete plans, accomplish tasks, build connections, and move projects forward. They show how to design every aspect of a meeting—from the way you greet people at the beginning to how you sum up at the end—so that real work actually gets done. Those who have adopted this system will never go back. Neither will you.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Using the same principles that make video games so engaging and that transformed the numbing assembly line into the dynamic shop floor, the Axelrods outline a flexible and adaptable system used to run truly productive meetings in all kinds of organizations—meetings where people create concrete plans, accomplish tasks, build connections, and move projects forward. They show how to design every aspect of a meeting—from the way you greet people at the beginning to how you sum up at the end—so that real work actually gets done. Those who have adopted this system will never go back. Neither will you.

—Tom Jasinski, Vice President of Human Resources and Global Head of Design and Change Management, MetLife, Inc.

“Most senior executives do not know how to make meetings productive. But as the world becomes more interdependent, meetings will become more frequent and a more necessary part of the work of organizations. Rather than waste time in and get mad at meetings, read this book and learn how to make them more productive.”

—Edgar H. Schein, Professor Emeritus, MIT Sloan School of Management, and author of Humble Inquiry

“Dick and Emily Axelrod have done an amazing job in their new book, helping us navigate through our most precious resource—time. The time we spend in conference room meetings is increasing, and Let's Stop Meeting Like This maps out a reliable process to maximize our return on investment in meetings.”

—Eric Lindblad, Vice President and General Manager, 747 Program, Boeing Commercial Airplanes

“This book will change your feelings about meetings and give them the importance they deserve. These ideas are the means to create communities of committed and powerful people.”

—Peter Block, author of Stewardship and Community

“Reading this book is invaluable time well spent. It's the most practical and instantly applicable resource available for not only revolutionizing meetings but providing effective and tangible ways people can work together productively and creatively.”

—Angeles Arrien, PhD, cultural anthropologist and President, Foundation for Cross-Cultural Education and Research

“Well-run meetings have a critical impact on the change process, so if you are responsible for significant transformational efforts, do yourself a favor and read Let's Stop Meeting Like This.”

—Daryl Conner, Chairman, Conner Partners, and author of Managing at the Speed of Change

“With this book you can create meetings that are engaging, productive, and intentional. Whether you are an OD practitioner, leader, or frequent meeting participant, the tools and approaches shared by Dick and Emily Axelrod can be quickly put into practice to achieve dramatic results.”

—Kim Gallagher Johnson, Director of Organizational Effectiveness, Allstate Insurance

“Let's Stop Meeting Like This has tangible advice and tools to get more commitment and better outcomes from meetings. I strive to have effective meetings but face the usual struggles of people feeling disconnected. Now I have the tools to transform my meetings from a task to a time to be innovative.”

—Terri Hill, President, Fortune 100 insurance company

“I'm not used to some of the creative recommendations that Dick and Emily make: Meetings should be voluntary? No ice breakers? Instead, whether we are facilitators, leaders, or meeting contributors, we're welcomed into a well-designed meeting and are left with much more confidence in our ability to carry out meetings well.”

—Jean Bartunek, Robert A. and Evelyn J. Ferris Chair and Professor of Management and Organization, Boston College

“The authors have created a perfect blend of lessons by stirring in illustrative stories to a brilliant blueprint for effective meetings. The result? The most engaging, no-nonsense, helpful guide I've ever read on this topic. Read it quick—before your next meeting!”

—Sharon Jordan-Evans, coauthor of Love 'Em or Lose 'Em

“With just the right balance of people and process, this book provides a great way to turn a negative into a double-positive—more productive meetings and increased levels of employee engagement.”

—Kevin Limbach, Vice President, US Operations, TaylorMade-adidas Golf Company

“This very clearly written book will be extremely helpful to leaders wishing to shift the workplace culture to be more effective and more relational.”

—Rabbi Deborah Prinz, Director of Program and Member Services, Central Conference of American Rabbis

“While I have organized and participated in many meetings during my career, I certainly learned a great deal about a subject I have taken for granted. This is a must-read for anyone who organizes or participates in meetings and seeks to make the experience more valuable and rewarding.”

—Thomas C. Homburger, former Chairman, Real Estate Division, K&L Gates

“The spirit of the book alone can transform the quality of meetings, but the memorable model it offers ensures a group can improve its meeting experience. One chapter on repairing meetings by itself is worth the full price of admission.”

—Ira Chaleff, author of The Courageous Follower

“The authors know what they are talking about and provide an easy-to-remember formula that actually works. Their book will make you smile in recognition and raise your eyebrows in appreciation of some new ideas.”

—Beverly Kaye, founder and Chairwoman of the Board, Career Systems International, and coauthor of Love 'Em or Lose 'Em and Help Them Grow or Watch Them Go

CHAPTER 1 – HOW TO GET YOUR WORK DONE IN MEETINGS

CHAPTER 2 – THE MEETING CANOE

CHAPTER 3 – THE WELCOME

CHAPTER 4 – CONNECT PEOPLE TO EACH OTHER AND THE TASK

CHAPTER 5 – DISCOVER THE WAY THINGS ARE

CHAPTER 6 – ELICIT PEOPLE'S DREAMS

CHAPTER 7 – DECIDE

CHAPTER 8 – ATTEND TO THE END

CHAPTER 9 – FIRST AID FOR MEETINGS

CHAPTER 10 – MEETING BASICS: Five Steps to Meeting Success

CHAPTER 11 – LEADERS: 3 Steps to Meeting Effectiveness

CHAPTER 12 – CONTRIBUTORS: 3 Steps to Meeting Effectiveness

CHAPTER 13 – FACILITATORS: 3 Steps to Meeting Effectiveness

CHAPTER 14 – OUR HANDOFF TO YOU

A POCKET GUIDE TO LET'S STOP MEETING LIKE THIS AND MORE

Works Cited

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MEET THE AUTHORS

THE AXELROD GROUP – THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY

CHAPTER 1

HOW TO GET YOUR WORK DONE IN MEETINGS

If you look at the way we meet in organizations and communities across the country, you see a lot of presenters, a lot of podiums, and a lot of passive audiences. This reflects our naiveté in how to bring people together.

PETER BLOCK

Have you ever fallen asleep on an airplane? Think about it. You are sleeping in a chair bolted to an aluminum frame, a few inches separating you from sixty-five-degree-below-zero (Fahrenheit) air, six miles up in the sky, going more than five hundred miles an hour. The information people share and the decisions engineers make in meetings at Boeing make this death-defying feat commonplace.

Eric Lindblad, vice president and general manager of Boeing’s 747 program, runs many of those meetings that allow you to sleep on planes. He has strong opinions about meetings. For one, he finds spending hour upon hour in crowded conference rooms a nightmare. He hates to see conference rooms full of “wall-hangers,” people who attend a meeting with no real purpose in mind. He really gets upset when he looks around the room and sees people whose body language indicates they would rather be anywhere else in the world. “Empty inside” is how Eric describes his experience in these meetings.

Eric believes the best way to lead change is to be out on the factory floor, working with production to implement needed changes, not in a stuffy conference room. Eric’s factory floor has fuselages, wings, tails, miles of cable, and seats. These parts come together in Renton, Washington, to make the finished product: a Boeing airplane.

Eric’s frustration with meetings started when he was working on the Boeing 737. That is when he came to his belief about how to lead change. He also realized his task required building teams, sharing information, and making decisions. Eric had to find a way to both be out on the floor and hold meetings.

Eric started by doing some simple math. He multiplied the number of people in his meetings by their average hourly rate and quickly realized that meetings are a very expensive form of communication. He also concluded that habits were behind a lot of meetings—for example, “We meet every Monday morning, no matter what.”

Eric dared to rethink his meetings completely

Eric sought to change these meeting habits by developing two criteria for determining whether to hold a meeting:

1. Is there a need to share information?

2. Does the information that needs to be shared require dialogue?

The answers would determine whether or not to hold a meeting.

Making sure the “right” people attended was next. He sought to eliminate all wall-hangers from his meetings. His attendance criteria limited attendance to people who

• Had information or knowledge to share

• Had decision-making authority

• Were vital to the issue at hand

Next he set about changing the culture of meetings

Eric sought to eliminate arriving late and leaving early. In consultation with his leadership team, he required all meetings within his organization to be scheduled to start five minutes before the hour and end five minutes after, no matter the length. Why? Because he found that people were scheduling meetings back-to-back with no time for transition. This made it impossible for attendees to get from one side of a cavernous assembly building to the other and be on time for the next meeting. We suspect the same holds true even in smaller office buildings.

Then Eric completely updated his approach to meetings

What Eric did next was extraordinary. He made all his meetings voluntary. There were no mandatory meetings on Eric’s watch. He wanted people to be there not because of threat or politics but because they wanted to be there.

He actually gave people permission to leave meetings that were not valuable. When he noticed people who looked like they would rather be somewhere else, he would ask them, “Would your time be better spent doing something else?” If the answer was yes or they didn’t have a good answer to the question, Eric would excuse them from the meeting—no repercussions.

Making meetings voluntary was Eric’s way of getting meeting feedback. If people stopped showing up to a particular meeting and Eric believed there was a need to meet, he then asked what people needed to make the meeting more effective.

Eric has been using his approach to meeting effectiveness for more than ten years, starting when he was a senior manager of structures engineering for the 737 airplane. Whenever Eric takes a new assignment, he says it usually takes a month for people to believe that he is serious about his approach to meetings.

What would happen if you made all of your meetings voluntary?

You may be like Eric, feeling that too many of the meetings you lead are time-wasting, energy-sapping affairs. Most may seem like useless gatherings endured at the expense of your “real work”—meetings that sabotage your organization’s goals and product while wasting human capital. You may be ready to imitate Eric and make your meetings voluntary. Are you shuddering? It could work, but only if you take a fresh look at meetings and update your approach. If you are ready to take the plunge, then you are reading the right book.

Even if you are not ready to make your meetings voluntary, you are still reading the right book. People always decide the extent to which they will be present in a meeting. If they don’t feel like they can leave, they leave in place; their bodies are present, but their minds are absent. No matter whether you make your meetings voluntary, people will still make choices about how much of themselves they bring to a meeting and how much of themselves they leave behind. You can influence that choice. We’ll show you how.

Getting your work done in meetings

Meetings can be places where people do meaningful work, make plans, reach decisions, make commitments, and grow and develop and where everyone decides to get behind a task. Meetings can be gatherings in which people look forward to participating, even though they don’t have the time, even though the e-mails keep coming, even though no one can pick up the slack while they attend.

Changing meetings from time wasting to time valued from energy sapping to energy producing, requires a different approach to designing, leading, and contributing in meetings. It means a change in direction. It means making new choices. We invite you to learn how to

• Transform meetings into productive work experiences using the same work design principles that transformed factory work and made video games engaging

• Identify the habits that work for and against energy-producing, time-valued meetings

• Identify the critical choices that meeting designers, leaders, and contributors make that transform meetings into productive work experiences

• Create a meeting environment where everyone puts their paddle in the water

A better way to paddle this stream

Prior to the 1970s, leaders viewed factory workers as extensions of the assembly line: interchangeable parts that required little training. These workers were expected to show up and do their job—no more, no less (Terkel 1972). This mind-set created an unprecedented level of dissatisfaction that resulted in autoworkers purposely sabotaging their product’s quality by placing defects into cars.

That all changed when companies such as Ford and GM introduced Quality of Work Life initiatives that featured quality circles, joint union-management improvement activities, and self-directed work teams. For the first time, systems went into place that supported employee participation in making workplace improvements. Factory workers found new freedom when, for the first time, any worker on the line could stop the line. The result: productivity soared, quality improved, and frequent sabotage of the work virtually disappeared. People learned new skills through cross training; they learned how to work together in ways they had never worked before. In some plants, employee groups scheduled production, handled their own discipline, created their own work schedules, and often worked without direct supervision.

Today’s popular work improvement processes, such as Lean Manufacturing and Six Sigma, stand on the shoulders of these earlier efforts. Now we take for granted that workers can contribute to the organization and, as a result, generate improvement ideas that benefit everyone. Leaders did not always think that way. What we have learned is that given the opportunity, people can make significant contributions to improving their organization’s productivity.

What do the factory and meetings have in common?

As workers did on those old factory floors, people often show up at meetings with low expectations. They don’t anticipate much will happen, they participate in decisions where the outcome has been predefined, they leave feeling that their time was wasted, and then at Starbucks and in the halls they complain about their energy-sapping, time-wasting meeting experience.

Because most meetings provide the mind-numbing experience of the assembly line, most people seek to reduce the pain by eliminating the number of meetings they attend and the time they spend in them. This is a human response. However, when you seek to eliminate meetings, you also eliminate the possibility of producing the innovative thinking, quality decisions, and collaboration and cooperation that can occur only when we meet. The choice, then, is to either

• Remove the pain by eliminating meetings

• Create more productive meetings

Why meetings are so energy draining

Emily is fond of telling about her experience with the PTA. She recalls a meeting to decide on the color of the cafeteria trays. The meeting dragged on for hours. In the end, the group did decide on a color: yellow. Fifteen skilled people spent hours on an inconsequential decision. Emily, frustrated by her experience, decided never to return.

You might ask why Emily, being the good consultant that she is, didn’t help the group reach a decision more effectively. Why didn’t she step in to end such mind-numbing discussion? The reason: she didn’t care. A meeting has meaning when you know that what you are doing is important, that the outcome will make a difference to you, to others, to the organization as a whole. What difference was the color of cafeteria trays likely to make?

You spend a lot of time in meetings: informal chats and huddles with your coworkers, as well as staff meetings, town halls, and major change initiatives. Some meetings take a few minutes; others are multiday affairs. Sometimes you meet with one other person; other times you meet with hundreds. Studies show that the amount of time spent in meetings varies by organization level, ranging from 20 percent to 70 percent of a day. In the United States alone, there are 11 million meetings daily (Koehn 2013). All of us are spending more time in meetings than we did five years ago, and this trend is expected to continue (Lee 2010).

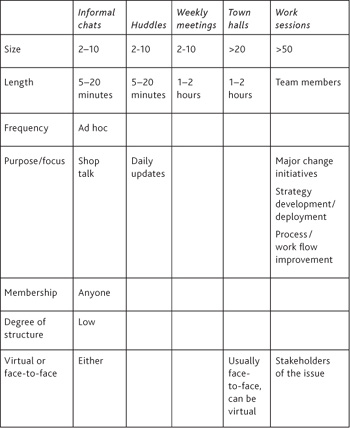

As shown in table 1.1, meetings range from informal chats involving two people to large-group, multistakeholder meetings. The larger the meeting, the greater the need for structure. (We are using “structure” here to mean the systems that guide the meeting process so that people can do their work effectively.) As you add more and different people to the conversation, variety increases, which allows learning and innovation to occur. The degree of preparation also increases as you move from informal to more formal gatherings.

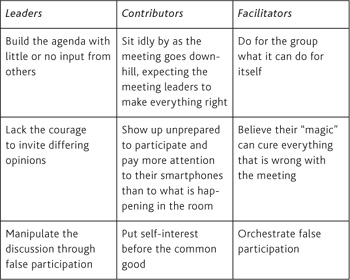

You put a lot of time and effort into meetings. The problem is that the effort is often misplaced. Any meeting includes three basic roles: leader, contributor, and facilitator. In some cases, a person with a formal organizational role may have the same role in the meeting. For example, the formal organization leader may be the discussion leader, or an HR person may be the facilitator. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Any meeting participant can lead the discussion, contribute, or facilitate the discussion. Table 1.2 identifies how these roles contribute to getting work done in meetings. They comprise an integrated whole, working to assure the meeting’s success.

Having one of these roles is not the same as effectively performing that role. Some leaders, contributors, and facilitators can actually work against the success of a meeting, as outlined in table 1.3.

Table 1.1 Where you spend your time

Table 1.2 Meeting roles and responsibilities

Table 1.3 How leaders, contributors, and facilitators work against success

Are you a meeting investor, beneficiary, or bystander?

No matter what role you play in a meeting, how you show up in that role is critical to the meeting’s success. Here are two examples. Our colleague Barbara Bunker is one of the most sought-after committee members at the University at Buffalo because in every meeting she attends, she invests in the meeting by asking herself what she can do to ensure the meeting’s success. If note taking is required, Barbara takes notes. If helping to resolve a conflict is required, she helps resolve the conflict. If the task is making sure everyone has a voice in the discussion, then that is what she does. Barbara’s investment helps ensure the meeting’s success.

Our editor, Steve Piersanti, takes a different approach. Prior to a meeting, he works to become a beneficiary by reviewing the agenda and asking himself two questions: “What can I contribute?” and “What can I gain?” His answers to these questions prepare him to be an active meeting participant. He answers the question, “Who am I here for?” by saying, “I’m here for myself and I’m here for others.” By contributing to the success of the meeting, Steve makes sure he is there for the larger group. By figuring out what he can gain, he makes sure that he meets his own needs.

In both cases, Barbara and Steve plan not just for the meeting but how they will show up in the meeting. They take responsibility for ensuring that the meeting is worthwhile, not just for themselves, but also for everyone present.

Barbara and Steve provide great examples of how you can invest in and benefit from a meeting. Being an investor in the meeting’s success means choosing to work for the good of the whole. Being a beneficiary requires you to work toward creating value for yourself. Together they are a powerful combination.

You can also choose to be a bystander. Bystanders don’t invest in the meeting’s success, nor do they work to achieve benefit from the meeting. They stand on the sidelines like the wall-hangers at Boeing, hoping something useful will happen. By making this decision they ensure the meeting goes nowhere. The choice to invest in or benefit from the meeting is a decision to work toward the meeting’s success. The choice to be a bystander is a decision to work for the meeting’s failure. What choice will you make in your next meeting?

Toward a more productive meeting

Everyone knows that effective meetings have a purpose and an agenda, and everyone knows you need more than these. Too much of the advice about improving meetings only offers boxes of Band-Aids. Instead, in the coming chapters, we will describe a seismic shift in the way to think about, plan, and execute meetings—no Band-Aids.

We will show you how to change the meeting experience from dread to engagement, from something you suffer through to something you find appealing. Whether you are a leader, contributor, or facilitator, success will require you to change the way you perceive, plan, and participate in meetings.

Success starts with conceiving of meetings as places where everyone does productive work. It means creating meetings where everyone feels responsible for the outcomes. These meetings carry five electrical charges (Csikszentmihalyi 1997; Emery and Trist 1960; Hackman and Oldham 1976)

• Meaning

• Challenge

• Learning

• Feedback

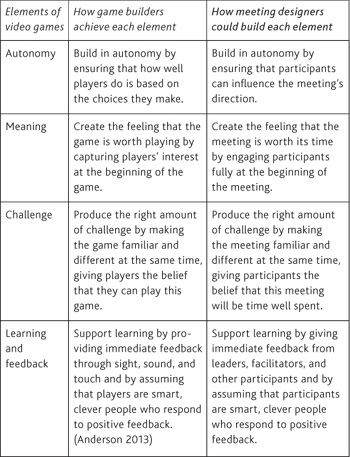

You can imagine our surprise when Colin Anderson, CEO of Denki, the company that created the award-winning video game Quarrel, approached us at a workshop we conducted and excitedly told us that these principles are similar to the principles his design team employs. We soon learned that the extent to which autonomy, meaning, challenge, learning, and feedback are present determines whether a player becomes engaged in playing a game. If you are thinking these are outdated principles that apply only to the factory floor, you are mistaken.

Now imagine how easily the elements of video games could transfer to meetings (table 1.4).

Judy Weber-Lucas, a senior organization development consultant, shared with us how she went from dreading meetings to actually looking forward to them. Here is her story in her own words:

I once had a client, Ken Aruda at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Maryland, who invited me to his weekly staff meetings. At first I dreaded them, but after experiencing his facilitation style, I actually looked forward to being a part of meetings where things got done.

Here’s how it worked:

Table 1.4 How elements of video games can transfer to meetings

1. Leader agenda items. The leader would arrive ten minutes early and record his items for the agenda on a whiteboard.

2. Team member agenda items. As team members arrived, they would add their agenda items to the whiteboard list. They arrived a couple of minutes early, knowing the meeting would start on time.

3. Time estimates. Once the meeting began, the leader would review the list and ask the agenda item owners to predict the number of minutes it would take to cover their topic. He wrote the number of minutes to the left of each agenda item.

4. Priority order. To assure the most important items got full coverage, he asked the team to prioritize the list of items from the most important to the least important. He recorded the priority order to the right of each agenda item.

5. Timekeeper and recorder. The leader asked for a volunteer to keep the team on task, according to the times allotted. The leader also asked for a volunteer to record conclusions and decisions made on each topic. Each topic needed only one or two sentences.

6. Items that run out of time. If an item warranted more than the predicted number of minutes, the leader would ask how much more time might be needed to complete the topic. Based on this prediction, he asked the group members if they were willing to allow more time immediately, at the end of the meeting, or at the next staff meeting.

The team decision determined the next step for this particular topic.

7. Closing. The leader asked the recorder to review the conclusions and decisions made for each topic to ensure team members knew their commitments.

Despite the time it took to set up the process at the beginning of the meeting, it ended up being a good use of team members’ time because they were “getting things done.” (Weber-Lucas 2013)

Autonomy was present in this meeting because people had control over what the group discussed and the discussion’s length. Meaning occurred when people discussed issues that were important to them. Challenge was present in the topics they addressed as well as an agenda that worked for all. Learning occurred as people addressed the topics. And feedback was provided as they reviewed the outcomes of the meeting. As a result of investing in the meeting, everyone benefited.

While her client did not have the benefit of knowing these principles or the Meeting Canoe system, Judy believes he came up with an approach that intuitively incorporated both.

Meeting success requires incorporating these concepts as we take a ride in the Meeting Canoe, our system for creating meetings where productive work happens. In the next chapter we’ll show you how. Before we do, we’d like you to ponder the following question.

Are meetings keystone habits?

Charles Duhigg has identified what he calls keystone habits: habits so powerful that if you change them, the whole organization changes. When Paul O’Neill became Alcoa’s CEO, he decided his number-one priority was to change safety habits throughout the organization. He modeled this when he began his first speech as CEO by informing people where the exit doors were and what they should do in case of an emergency. To everyone’s surprise, he never once talked about his profitability or productivity goals. Throughout his presidency he focused on changing safety habits because he believed they were the keystone to productivity improvement. In doing so, he changed Alcoa into both a profit machine and a safety exemplar (Duhigg 2012).

We invite you to consider meetings keystone habits. What might happen if you changed the way you meet? What ripple effects might occur throughout your organization? What difference would changing your meeting habits make? Could it be that focusing on meetings is similar to focusing on safety? Starting with Eric Lindblad and throughout this book, we will show you how to change the way you meet and the dramatic changes that can occur as a result. Our journey continues in the following chapter.

KEY POINTS

• Making meetings voluntary and treating meeting participants as volunteers will make you rethink your approach to meetings.

• Meetings range in size from two-person chats to large-scale

• Leader, contributor, and facilitator are roles critical to any meeting’s success.

• Meeting investors and beneficiaries work for the meeting’s success, while bystanders contribute to its failure.

• Effective meetings carry the electrical charges of autonomy, meaning, challenge, learning, and feedback.

• Meetings can be considered keystone habits.

MAKE IT YOUR OWN

• Try making meetings in your organization voluntary.

• Treat meeting participants as if they were volunteers.

• Identify the role you play in a meeting as leader, contributor, or facilitator. Ask yourself how well your role contributes to the meeting’s success.

• Decide how you will show up at your next meeting. Will you be a meeting investor, beneficiary, or bystander?

• Build autonomy, meaning, challenge, learning, and feedback into your next meeting.

|

Role |

Responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

Leader |

Convenes the meeting; assures that the purpose for meeting is clear and compelling and that the right people are present Leads the meeting, making sure the group stays on task |

|

Contributor |

Offers the ideas and participates in the discussion Brings needed information to the meeting or acts in a way that facilitates the group’s working effectively |

|

Facilitator |

Assists the group in achieving its purpose Takes responsibility for timekeeping or posting information on smart boards Facilitates discussion by making sure the participants’ voices count and helping to resolve conflicts that may occur |