Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Moral Capitalism

Reconciling Private Interest with the Public Good

Stephen Young (Author)

Publication date: 12/03/2003

- Shows how to ensure that capitalism promotes progress and equality rather than enriching the few at the expense of many

- Based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an international network of senior business executives from such companies as 3M, Canon, NEC, Bankers Trust, Shell, Prudential, and dozens of other companies

- Provides practical guidelines for corporate social responsibility through the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business

The world is drifting without a clear plan for its economic development. Communism is dead, but in the wake of Enron and similar scandals, many see capitalism as amoral and too easily abused. A blueprint for progress is needed and Moral Capitalism provides one.

Moral Capitalism is based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an extraordinary international network of top business executives who believe that business can-and must-weigh both profit and principle. Caux Round Table's global chair, Stephen Young, argues that the ethical standards inherent in capitalism have been compromised by cultural values inimical to capitalism's essentially egalitarian, rational spirit, and distorted by the short-sighted dog-eat-dog doctrines of social Darwinism into what he calls brute capitalism. He demonstrates how the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business can serve as a blueprint for a new moral capitalism, and explores in detail how, if guided by these principles, capitalism is really the only system with the potential to reduce global poverty and tyranny and address the needs and aspirations of individuals, societies, and nations.

- Shows how to ensure that capitalism promotes progress and equality rather than enriching the few at the expense of many

- Based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an international network of senior business executives from such companies as 3M, Canon, NEC, Bankers Trust, Shell, Prudential, and dozens of other companies

- Provides practical guidelines for corporate social responsibility through the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

- Shows how to ensure that capitalism promotes progress and equality rather than enriching the few at the expense of many

- Based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an international network of senior business executives from such companies as 3M, Canon, NEC, Bankers Trust, Shell, Prudential, and dozens of other companies

- Provides practical guidelines for corporate social responsibility through the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business

The world is drifting without a clear plan for its economic development. Communism is dead, but in the wake of Enron and similar scandals, many see capitalism as amoral and too easily abused. A blueprint for progress is needed and Moral Capitalism provides one.

Moral Capitalism is based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an extraordinary international network of top business executives who believe that business can-and must-weigh both profit and principle. Caux Round Table's global chair, Stephen Young, argues that the ethical standards inherent in capitalism have been compromised by cultural values inimical to capitalism's essentially egalitarian, rational spirit, and distorted by the short-sighted dog-eat-dog doctrines of social Darwinism into what he calls brute capitalism. He demonstrates how the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business can serve as a blueprint for a new moral capitalism, and explores in detail how, if guided by these principles, capitalism is really the only system with the potential to reduce global poverty and tyranny and address the needs and aspirations of individuals, societies, and nations.

- Shows how to ensure that capitalism promotes progress and equality rather than enriching the few at the expense of many

- Based on principles developed by the Caux Round Table, an international network of senior business executives from such companies as 3M, Canon, NEC, Bankers Trust, Shell, Prudential, and dozens of other companies

- Provides practical guidelines for corporate social responsibility through the Caux Round Table's Seven General Principles for Business

Stephen Young is the global executive director of the Caux Round Table and is president of Winthrop Consulting and the Minnesota Public Policy Forum. He was formerly the third dean of the Hamline University School of Law, an assistant dean of Harvard Law School, and has worked with the Council on Foreign Relations and consulted to the United States Department of State.

For more information on the Caux Round Table, including a list of members and the full text of its Principles for Business, see www.cauxroundtable.org.

"This book gives us a practical guide to achieving better outcomes in business ethics and to reducing the harmful effects of globalization."

:

Preface

- Is a Moral Capitalism Possible?

- The Many Varieties of Capitalism

- Brute Capitalism: Survival of the Fittest

- Moral Capitalism: Using Private Interest for the Public Good

- Moral Capitalism and Poverty:Must the Poor Be With Us Always

- The Caux Round Table: Advocate for Moral Capitalism

- Customers: The Moral Compass for Capitalism

- Employees: Parts for a Machine or Moral Agents?

- Owners and Investors: Exploiters or Potential Victims

- Suppliers: Friends or Foes?

- Competitors: Repealing the Law of the Jungle

- Community: Enhancing Social Capital

- Principled Business Leadership: Stepping up to the Challenge of Moral Capitalism

Appendix I

Appendix II

Notes

Index

About the Author

CHAPTER 1

IS MORAL CAPITALISM POSSIBLE?

The mind of the superior man is conversant with righteousness; the mind of the mean man is conversant with gain.

—Confucius, The Analects, Bk. IV, Chpt XVI

As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence.

—Federalist No. 55, Friday, February 15, 1788

THIS BOOK AFFIRMS that moral capitalism is possible. First, in Chapters 1 through 5, it justifies faith in moral capitalism; then, in chapters 6 through 12, it provides a practical guide for those who want to achieve moral capitalism in their business pursuits and professional undertakings. Finally, in a concluding chapter, it discusses how, in these times, we can cultivate leadership sufficient to build a moral capitalism.

Seeking market profit through business and the professions is honorable and worthy. Based on the ideas and principles set forth in these chapters, I believe that each of us can indeed go to work every day for any business, great or small, feeling genuinely happy and proud of our career commitment.

For those more removed from careers in business, this book affirms a vision of social justice: that moral capitalism is the most appropriate means by which our modern, global human civilization can empower people and enrich their lives materially and spiritually.

The understanding of human potential that I present in this chapter is not just mine. I have endeavored to link its main features to the thoughts and writings of great minds from different cultures throughout the centuries. In 1994, business leaders from Japan, Europe, and the United States met as a round table discussion group in the little Swiss mountain hamlet of Caux and proposed certain principles for moral capitalist decision making. These Principles are known as the Caux Round Table Principles for Business.

For several years now I have come to know these Principles well through my work as the global executive director of the Caux Round Table organization. I have seen them affirmed by experienced and successful business leaders in many cultures. The Caux Round Table Principles are a concentrate of moral, ethical, philosophical, and jurisprudential wisdom from many traditions. We have explored how they reflect teachings from Chinese moral philosophy, Islam, Hinduism, African Spirituality, Judaism, Roman Catholic social teachings, Protestant insights, Japanese Shinto, Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism, and the ethical traditions of native Meso-American peoples.

Importantly, however, the Caux Round Table Principles also draw wisdom from successful business accomplishment. Written by senior business leaders, these Principles combine social virtue and self-interest into one way of doing business. In this book, I present my view as to how the Caux Round Table Principles for Business justify and structure a moral capitalism for the world.

THE MOST PROFITABLE BUSINESS COMBINES VIRTUE AND INTEREST

A successful business maximizes the present value of future earnings. The first requirement, therefore, of business success is sustainable profits. Onetime winnings, in business as in casinos, are disappointing. We expect more from our investments than that.

To sustain our profits over time, we need to replenish the capital we invest in the business. That capital comes in five different forms: social capital, reputational capital or “goodwill,” finance capital, physical capital, and human capital. These forms of capital are the essential factors of production. We must pay for them out of the earnings of the business. A business that neglects to pay for its capital will soon lose access to capital. Then it will quickly lose its profitability. Failure results when capital flows are insufficiently nourished.

Social capital is provided by society; it is the quality of laws, the cultural and social institutions, the roads, ports, airports and telecommunications, the educational achievements, the health and value environments that encourage or discourage successful enterprise.

Reputational capital adds value to a business by attracting and keeping customers, employees, investors, and suppliers. Finance capital is the classic form of capital: access to money. Physical capital is land, plant, and equipment. And human capital embraces the quality, creativity, loyalty, and productivity of employees.

When a business contributes to social capital, it is acting responsibly and ethically. When a business invests in its reputation, it better serves the needs of consumers and meets the expectations of society. When a business invests in its human capital, it provides better lives and working conditions for its employees.

In preserving its access to these necessary forms of capital by paying a return on capital from earnings, a business acts from self-interest but promotes social well-being at the same time. The selfish pursuit of the “bottom line,” therefore, leads a responsible business to satisfy the needs of others. The consequences arising from self-interest when a business seeks to maximize sustainable profits is selfish from one perspective but simultaneously moral from another.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the cycle of a successful, self-sustaining business. In one half of the cycle, five forms of capital inputs are converted by the business into a good or service for sale to a customer for a profit. Then, along the bottom, Figure 1.1 illustrates the other half of the business success cycle—the reverse flow of profits paid out as a return on all forms of business capital.

The successful business stays in business; it repeatedly cycles capital through the production of goods and services to please customers and make an attractive profit for itself. It maintains the adequacy of its capital inputs just as it continually attracts customers willing to buy its product or service. Michael Porter advises, “Gaining competitive advantage requires that a firm’s value chain is managed as a system rather than a collection of separate parts.”1

The wise steward of enterprise makes a profit in ways that preserve access to all forms of capital. The enterprise is not self-contained and self-sufficient but, rather, is importantly dependent on inputs controlled by others. It must please others in order to prosper. That service is a moral activity, subordinating self to what is beyond the self.

In his books Built to Last and Good to Great, business researcher Jim Collins discovered in successful companies what he called the “genius of And.”2 This was an ability to embrace both extremes on a dimension, such as purpose and profit, continuity and change, freedom and responsibility. Suboptimal performance resulted when companies felt forced to choose one goal over the other. These companies fell victim to the “tyranny of the Or.” Collins’ findings support the insight that capitalism can indeed avoid choosing self-interest over virtue.

One dollar invested in Collins’ good to great companies in 1965 had compounded stock returns of $471 by 2000. On the other hand, that same dollar invested in his group of direct comparison companies earned a cumulated return of only $93 during those thirty-five years.

Professors John P. Kotter and James L. Heskett of Harvard Business School found that companies with embedded cultures of respect for customers and employees as well as for stockholders outperformed companies without such a culture by a huge margin during an eleven-year period. The more successful companies grew their stock prices by 901 percent versus 74 percent for the less successful companies. Net incomes grew by 756 percent in the successful companies but only 1 percent in the others.3

In April 2003, London’s Institute for Business Ethics published a study of United Kingdom companies showing that those companies with corporate codes of ethical conduct achieved profit-turnover ratios 18 percent higher than comparable companies without a similar explicit commitment to conduct business ethically. Companies with ethical codes also generated significantly more economic value added (EVA) and market value added (MVA) and exhibited less volatile price-earnings ratios for their shares.4

BUSINESS MORALITY: “SELF-INTEREST CONSIDERED UPON THE WHOLE”

Distinct from academia, politics, and bureaucracy, business enterprise calls for constant action and decision making. Every decision, every action, comes with risk of loss or even failure. Judgment must be applied in each instance to consider alternatives in order to, hopefully, minimize risk.

In Figure 1.1, each component function of a sustainable business—the capital employed, the conversion of capital into a product, the product, and the sale to customers—requires decision making. Just consider what must be attended to in a successful business: how to acquire cash, where to have a factory or office, who to employ, what to produce, how to produce it, how to market and advertise, what price to place on the product or service, how to deal with customer needs and concerns, etc. Every course in an MBA program and every business book offered for sale address these and similar decisions that have to be made in business.

By what criteria can we say that these business decisions are moral?

I answer: “By the extent to which business decisions take into account the needs and concerns of others.”5

We are in business to serve ourselves and our needs, yes, to be sure. But reflection on our circumstances brings wisdom that we are not self-sufficient. We prosper through our interaction with others. One would easily conclude that, therefore, our prosperity is most secure where others wish and seek to help us be prosperous.

Our needs and preferences intersect from time to time with the needs and preferences of others. The more we take into account the needs of others when seeking to meet our own needs, the larger the overlap between our self-interest and our virtue. By taking into account only our own needs, we shrink the zone of overlap until we make ourselves morally irrelevant to others. When the zone is very small, we most often turn to means of manipulation, fraud, and coercion to impose our needs on others. We then act immorally and unethically.

That frame of mind which makes for a larger zone of overlap between our needs and the needs of others has often been called “enlightened self-interest.” I prefer to use the term suggested by the philosopher Thomas Reid, the Scotsman who succeeded Adam Smith in holding the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Glascow in 1766. Reid referred to the zone of overlap as our “self-interest considered upon the whole.”6

When virtue speaks to us, its voice may be too soft for us to hear. But where virtue is supported by the claims of interest, our resolve grows stronger to achieve what both virtue and interest jointly propose. The juncture of both motivations is crucial for virtuous conduct to prevail for most of us.

When we find a vocation, we fall on such a happy coincidence of virtue and interest. We benefit materially from our work, finding satisfaction in those self-interested accomplishments. And, simultaneously, we perceive our efforts to be in support of higher purposes as well, giving us rare and valuable levels of satisfaction and self-appreciation. We have found a becoming “fit” between ourselves and moral meaning.

When one is called to a task, work is transformed from something mean that we begrudge into that which nourishes us with life-giving energy and even delight. We are better to ourselves and to others when we fall into a vocation. Then, we prosper fully; everything is more real and more sustaining. We are happy; we have found our right way.

The possibility is reflected in the now trite comparison of three artisans. When asked what they are doing, one mason replies, “I am cutting stone.” The second says, “I am building a wall.” But the third says, “I am building a cathedral for the glory of God.” The first two men have jobs; the third has found a vocation. For him, virtue and interest have fused into one calling.7

We have learned under principles of quantum physics not to see reality as separated “things” walled off from one another by boundaries. Subatomic activity arises from the interaction of fluid potentials, not from hard particles bouncing into each other. Whatever there is is both matter and energy. Whether it is one or the other depends on how we humans conceptualize it. Reality can look like matter and yet act like energy. As these subatomic chameleons interact with one another in our bubble chambers, they appear temporarily in our scientific instruments as up to 12 different particles.8 But are they really 12 different Newtonian and Cartesian “things”?

As Margaret J. Wheatley writes: “There is no need to decide between two things, pretending they are separate. What is critical is the relationship created between two or more elements.”9 Similarly, at the level of the human, both virtue and self-interest can inhere in the same action. Which human potential prevails—either virtue as a check on self-interest or self-interest as a deviation from virtue—depends on the actors, the energy fields surrounding them, and the issues of the moment. To say that an action is either pure virtue or crass self-interest reflects intellectual poverty, conceptualizing only the two polar extremes, while ignoring the zone of overlap where self-interest is “considered upon the whole.”

Looking at the effects of time gives another perspective on the overlap of self-interest and virtue. Decisions made for our short-term advantage often bring negative long-term consequences that can far outweigh in their effects any advantages we have initially gained. Thus, in business, the results of fraud are short-term profit but, once discovery of our deceit occurs, our fraud brings about long-term and possibly permanent corruption of our ability to get what we want from others. Whenever we focus on the short term, we tend to minimize our goals, falling victim to the tyranny of the “Or” and forgetting the genius of the “And.”

CAN WE OVERLOOK BIBLICAL TEACHINGS AND SERVE BOTH GOD AND MAMMON?

The Christian tradition teaches us to choose between God and Mammon and to lay up our treasures in Heaven and not to seek them among earthly things. The Christian Gospel of Matthew explicitly assigns all earthly powers and attractions to the dominion of Satan, a dominion rejected by Jesus on the grounds that “Man does not live by bread alone.”10

Wise prophets over the ages in many cultures have urged people to turn away from the things of this world. To become divine, the flesh must be mortified. Must we, however, choose only between God and Mammon? Can we not live with the pressures of markets and under the influence of money and still set before ourselves every day certain reasonable expectations of behaving justly in the eyes of the best angels of our nature?

The Caux Round Table Principles for Business call on a tradition of moral character in seeking to live by a third way—one in this world but guided by higher aspirations. I have learned from reading philosophers such as Hegel that moral visions arise from the human mind. They are not natural in the sense that rain and snow and gravity are natural. They find their role in life though the application of human will and in human actions. Without human action, there’s no morality that we can see, touch, or feel. A moral capitalism, therefore, asks that, in their business affairs, people use willpower to check and balance abusive internal forces such as greed and temptation; that they strive to expand the zone of overlap between virtue and self-interest.

Indeed, we can seek profits for ourselves in the markets of capitalism without becoming mean or avaricious. Leaders of the Caux Round Table such as Frederik Philips of the Philips Company in The Netherlands; Ryuzaburo Kaku, CEO of Canon; and Winston Wallin, CEO of Medtronic, have done so. Both Mencius in ancient China and Adam Smith in eighteenth-century Scotland argued that we have within us a powerful moral sense, which, if attended to, can lift us above our potential for being only base and mean.

The prominent contemporary German philosopher and sociologist Jurgen Habermas has noted that we live aware of a realm of “normativity,” which is conceptual and linguistic, but in a realm of “facticity,” which is more tangible, objective, specific, and determinative of our physical conditions. Through the medium of action, however, we can impose normativity on the facticity around us.11 A moral capitalism, therefore, would have us do as Habermas suggests: impose norms on our behaviors in seeking profits.

Capitalism is of this material world; it provides us with the means to live; it empowers us within the known world of sense and human reason. If it is to be measured by a strict standard of holiness, by religious normativity alone, then there can never be a moral capitalism.

Since it belongs exclusively to this world of sorrow and sin, this existential realm of facticity, moral capitalism cannot require our spiritual perfection, only that we seek always to do better than heed our base inclinations. Moral capitalism, nevertheless, asks much of our potential for humanity. It asks that we activate something of the divine within our world of facts and death, that we guide our passions by our chosen virtues. Moral capitalism seeks to infuse the teachings of philosophy and the wisdom of religion into the search for profit.

Can we do this? Can you do this?

If so, moral capitalism is possible; if not, its strictures are only a kind of misleading vanity, the rhetoric of a secular piety.

Plato and Aristotle were in agreement that the life of aspiration was one where some personal capacity of willpower governed the passions. People, Aristotle thought, could work their way to happiness through the forming of ethical habits. Jesus Christ preached parables to encourage his audiences to put aside selfish pursuits, the better to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. In India, the Gautama Buddha provided a complex theology of seeking escape from desire, sensation, and striving. The Koran revealed to Mohammad instructs many times that people will enter Heaven only if they have faith and do good works of benefit to others. The goals set by Allah, therefore, are not those of selfish cravings or the abusive prerogatives that come with possession of earthly power.

Confucius drew a dichotomy between those who had mastered their base instincts and those who had not. Those possessing mastery, he called “lordly” or “superior” persons. Those still in thrall to their selves he called “small” or “mean” persons. He made the following distinctions between these two categories of people:

“The superior man does not even for the space of a single meal, act contrary to virtue.”12

“The master said is virtue a thing remote? I wish to be virtuous and lo! virtue is at hand.”13

Today, we need not be as restrictive in our categories as Confucius was. There are doubtless intermediate steps between the conflicting extremes. The propensities for both good and evil are truly mixed within most of us.

In China, not long after Confucius drew attention to his faith in the constructive impact of moral capacity, another Chinese, Fan Li, assembled twelve axioms for success in business. Fan Li was also known as Tao Zhu Gong, so his axioms have come down to us as the “Business Principles of Mr. Tao.”14 Tao Zhu Gong evidently believed that living by principles can make a difference in your life. His principles have been followed by Chinese business families for centuries.

Under the new science of quantum physics and chaos theory, order and form in the universe are not created by complex controls and commands. Our reality, rather, results from the active presence of a few guiding principles or formulas repeating back on themselves through the operation of individual freedom for highly autonomous decision makers within the overall system.15

Every person has some capacity for acting ethically. Both Mencius and Adam Smith vividly argued that humans are a distinct species due to a capacity for moral awareness.

All of us possess the capacity—weak or strong, proven or untested—to align our behaviors with our will and our better understanding. We act not always from raw instinct, unguided and unpredictable. We have interests we seek to further, ideals we value, emotions that move us, and self-concepts and personalities that govern our interactions with others. We also have what the ancient Chinese called a “calculating mind.” We look into the future as best we can and take action today to achieve specific results later. Our minds may be clouded by emotions or poor judgment, but the psychological and moral machinery of following some specially chosen course always remains in place within us.

Starting the engine of morality and bringing it to full throttle are the tasks of parenthood and socialization. People must learn to be good; they are not born good, only with the seeds of goodness in them. Buddhists refer to that capacity as the Buddha mind within us, resting until awakened. Taoists claim that washing the mind free of thoughts brings us to the point of appreciation of truth, the Tao, and suddenly therefore to an ability to act correctly. Jesus said, “The Kingdom of Heaven is all around you, yet you see it not.”16

Contrary to advice to conform to moral principle is the reasoning of Sigmund Freud. In his little tract Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud argued that building moral society, or “civilization” in his terms, required repression of instincts and passions.17 In his mind, this systematic repression led to neurosis in the individual, which as a result turned Freud away from efforts to instill rigorous moral faculties in the young.

Yet people can’t live without the moral dimension. First, we are not emotionally self-sufficient, but are social, born both into society and for it. We have needs for love, esteem, and consideration, which only others of our species can supply.18 Morality reflects the regard for others that arises in a social setting. Ethics is the course of conduct that makes room for others in our decision making.

Second, we have an unquiet consciousness of reality. We feel fear looking out on an often unforgiving cosmos that gives us little evidence of our importance to it. Where we find genuine and lasting psychological rest and inner comfort is not in material things.

FINDING THE PERSONS WHO WILL BUILD MORAL CAPITALISM

Others have noted the proclivity of people to act from a range of morally worthy motivations. For example, the Harvard psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg provided a well-known set of stages of moral development.19 Individuals in stage 1 sought avoidance of punishment and deference to power. Stage 2, higher in moral capacity, was action calculated to satisfy one’s own needs and occasionally the needs of others. In stage 3, good behavior is that which pleases or helps others and conforms to social stereotypes. In stage 4 we seek to do our duty and obey legal norms, maintaining the social order for its own sake. In stage 5 we assert our rights as society gives them to us, using contract to obtain binding obligations. Then, finally, in stage 6, right is defined by the decision of conscience in accord with self-chosen ethical principles appealing to logical comprehensiveness, universality, and consistency.

In Kohlberg’s typology, stage 6 would have our self-interest consider a vast range of needs and concerns embracing a very large number of other people. Perfectly moral capitalism would require us to use only Kohlberg’s stage 6 reasoning in business decision making.

Robert J. Spitzer, Jesuit and Doctor of Philosophy, now president of Gonzaga University, gives us a similar hierarchy of starting points for moral undertakings. He believes that there are four main desires or drivers in the human personality. At the lowest moral level is immediate gratification, that is, actions taken to maximize our pleasure and minimize our pain. Second is ego achievement, that is, promotion of self and gaining advantage over others. Third is to do good beyond the self, invoking principles such as justice, love, and community. Here, intrinsic goodness is an end in itself, and leadership of others becomes possible. Fourth, and highest, is participating in giving and receiving ultimate meaning, goodness itself, and living with ideals and love.20

If moral capitalism will need people willing and able to seek out moral considerations—the higher levels of consideration noted by Kohlberg and Spitzer—and apply them in their lives, where will such people be found?

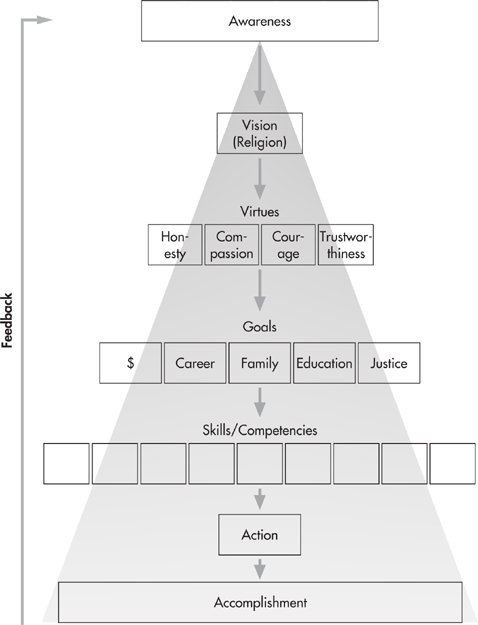

Figure 1.2 roughly illustrates how ethics work in individual lives. It needs to be understood before we can invoke moral power to drive the dynamics of capitalism.

Figure 1.2 represents the dynamics of human action as seen by moral philosophers. At the top of the pyramid is a realm of abstract thought and understanding, what Habermas called the realm of normativity. This realm is beyond nature and exists only in human consciousness.

At the bottom of the pyramid is the realm of action, what Habermas called the realm of facticity. The objective of morality is to impose on the level of action goals and ideals drawn down from the realm of abstract normativity. The force that draws goals and ideals out of inner awareness and imposes them on the life world is human willpower and decision making.

At the highest level of abstraction, which I believe is consistent with the teachings of Buddhism, Taoism, Adam Smith, and Mencius and with Jesus Christ’s references to an invisible Kingdom of Heaven that is all around us, lies an awareness of life and existence that we find very hard to put into words. It is what Smith and Mencius called the “moral sense”; it is most easily approached through prayer and meditation; we have possession of it when we find a “Zen mind.”

At a lesser level of abstraction, at a level of spoken thoughts and written conceptions, we find religious understandings. These are guiding visions to us of how the world works and what our purpose in life is to be. We come to these beliefs through reflection, education, reading, discourse, and listening to the insights of others.

Dropping down to the next level, we begin to engage the world. We define our identity by bringing certain virtues into our behavior. Practice and the formation of habits inculcates virtues into our lives so that we live them out spontaneously, without questioning our actions or our motivations. At this level we find Spitzer’s fourth and most admirable set of good motivations. In the Confucian paradigm, here is where a person would be either “masterful” or “mean.”

At this level we are often conflicted in our decision making. Pressures from others to conform to their values and desires, the psychic weight of a superego or a moral code implanted by parents or social tradition, and the conflict between virtues and immediate advantage strain the alignment of our character with our religious insights and beliefs. Developing powers of reflective self-control, finding mentors, and building good habits are tools to help us manage these conflicting pressures.

Next, dropping down to the level of setting goals and of calculating what is in our best interest, the possession of courage and practical wisdom and the finding of mentors and coaches are very helpful. Finding that equilibrium between the extremes of pure virtue and raw self-interest that is called “self-interest considered upon the whole” is relevant here.

Kohlberg’s stages of reasoning have their application at this level of response to life’s opportunities. Do we set as goals narrow and self-serving concerns described in his stage 1? Or, do we set our course to implement higher notions of universal justice and good?

The American psychologist Abraham Maslow offered a now widely accepted way of thinking about our personal goals. He made a distinction between the value set of individuals focused on meeting their basic needs and the value set of more secure and high-minded persons.21

Persons who, in Maslow’s framework, act from the more basic set of needs accentuate “D” or “deficiency” values. Their goal is to make up for felt or perceived deficiencies. Their value set subjects them to fears of self-betrayal, to living by fear, and to anxiety, despair, boredom, inability to enjoy, intrinsic guilt and shame, emptiness, and lack of identity.22 These people are always grasping for power with which to reassure themselves that they are “somebody.” The person whose goals seek to remedy deficiencies is likely to look on others as a means-object, a source of money, food, security, or such. Seeking only to overcome deficiencies inhibits full awareness of mutuality and of reciprocity in social settings.

A capitalism dominated by people seeking to overcome deficiencies would be most unpleasant. It would likely fit Thomas Hobbes’ famous definition of humanity living outside of conventional social norms, where life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”23

The goals of high-minded persons (who possess what Maslow calls “B” or “being” values) include “justice, completeness, oughtness, fulfillment—telos and finis, fairness, structure, order, honesty, essentiality, beauty (perfection, rightness, completeness), goodness, effortlessness, truth, honesty, self-sufficiency (not-needing-other-than-itself-in-order-to-be itself).”24

Maslow asserted that persons seeking these “B” goals tend toward serenity, joy in living, calmness, acting with responsibility, and having confidence in their ability to handle stresses, anxieties, and problems.25 Presumably, people influenced by Maslow’s “B” values when making decisions in the midst of market pressures would be more likely than not to leave room in their calculations for long-term consequences, for win-win relationships, and for acting with honor and integrity. Their word would be their bond. They would refrain from brutish actions.

Once we have settled on appropriate goals, to achieve them we pull together related skills and develop the personal competencies that others require from us. Education, training, and gaining experience are the means we all have to accomplish this task. But, here we need to be aware of our distinctive talents and abilities and not force ourselves to acquire competencies too much at variance with our natural genius. Assessments such as the Myers-Briggs inventory of personality styles are very revealing and helpful in guiding us towards work in which we can succeed and better align ourselves with our highest aspirations.

Once we have set goals and have put ourselves in a position to reach them, we take action and build a record of accomplishment. When our accomplishments conform to our highest aspirations, we have found our vocation.

Since it is not impossible for people to act from “self-interest considered upon the whole,” we should demand such conduct from more and more people in business. The quality of ideals that a person, or a society, or a corporate culture, places at the apex of a value hierarchy, then, has not-to-be-overlooked implications for the quality of life to be lived by that person, society, or corporation.

Understanding how people can and do bring morality into their decision making illuminates an answer to the question of whether moral capitalism is a realistic possibility. The short, affirmative answer lies in training and developing people with the capacity for moral decision making. The more such people set the rules for capitalism, the more capitalism will become.

CHOOSING THE MORAL WAY

Morality is a very personal decision to will what is right. Acting ethically is a test of leadership and is an act of culture. Moral capitalism is nothing other than a decision-making culture created and sustained by individuals acting from principle, regardless of their position in a formal bureaucratic hierarchy.

With reflection, prayer, meditation, and conversation, and by using our intuition to obtain inspiration and wisdom, each of us can deepen our awareness of what life is and can more and more clearly formulate our vision of who we are, of where we are, and of where we need to go. The capacity for cultural leadership, our moral sense, is right at hand, just as Confucius advised and Adam Smith took for granted. Each of us can be a leader for moral capitalism.

But it is wrong, in my mind, to require of any person that he or she live a life of saintly perfection. We are, after all, only human. Adam and Eve, relates the biblical story of Genesis, were banished from the Garden of Eden not only because they ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge forbidden them but also because they might also eat of the tree of life and become like the divine immortals. Icarus flew too close to the sun, melting the wax of his man-made wings and falling to his death. Christian story and Greek myth both point to a single truth: the proper scope of human ambition is this-worldly. To do more is to risk idolatry, where we humans replace God with an illusion of human perfection.

To demand that we live in the world according to the strict commands of virtue alone points us awry. That way a certain form of madness lies. The experience of earthly theocracies has not been encouraging: consider the realities of Savanarola in Florence, Calvin in Geneva, Robespierre in France, Lenin in Russia, the Ayatollahs in Iran, and Pol Pot in Cambodia. Attempts to govern through pure virtue have lead to many deaths and much suffering.

We need only ask for the presence of mind—and the underlying character sustaining such a mind—to manage the tension implicit in the overlap of virtue and self-interest, the zone of “self-interest considered upon the whole.”

GLOBALIZATION: INTENSIFYING THE CULTURE OF SELFISHNESS AND GREED

Yet, for many of us, the especially seductive Siren call of our passions and desires drowns out the appeal of other-regarding values.26 Not everyone who hears the Sunday sermons will be saved on Judgment Day. Modern capitalism, by accelerating wealth creation and the provision of middle-class consumer comforts, poses a special challenge to moral leadership. The culture fostered by globalization undermines our individual and our collective capacity to choose “self-interest considered upon the whole.”

The creation of a global culture of “teenagerism,” propelled by consumer wealth, has commodified greed.27 Thanks to the vast increases in productive forces, human identity now very easily, and more than ever before, grounds itself in possessions, not in ideals.

The “teenager” is a modern phenomenon following the emergence of a special kind of middle-class family. Before the 1950’s, humanity never knew true “teenagers” in the sense of James “Rebel Without a Cause” Dean, Elvis Presley, The Beatles, and, now, Britney Spears.

Most sadly, through the enticements of globalization, the American culture of the free-spirited, free-spending, free-of-responsibility teenager is taking over the world, one youth at a time. The cult is now worldwide, with MTV promoting rap culture in South Korea and young Thai girls dressed as Britney, exposing to the public dainty and well-formed belly buttons just as she does.

In another spreading form of juvenile cheekiness, European roadways and fences are often decorated with graffiti inspired first by angry young African American men down and out in New York City putting their rather elegant “tags” on subway cars.

Everywhere, parental authority is on the defensive. The holdouts are tightly knit religious communities like the Mormons and fundamentalist circles in Islam, Protestant Christianity, and Judaism, which isolate themselves from the trends of modern times.

The teenager is more than a child but less than an adult, spending money on tentative self-definition through clothes, shoes, music, and other accoutrements. Teenagers are in escape from responsibility, seeking to postpone adulthood as long as possible. They build for themselves a culture of follow-ership, where the restraints of moral leadership trigger fear and loathing.

And, since its birth in the 1950s, “teenagerism” is drawing to its ranks older and older Americans. As the baby boomers age into their fifties, their earlier cultural proclivities as teenagers remain active, seeking cultural space and economic resources with which to subdue opposition from adult responsibilities. They use their careers, in business or elsewhere, not to help others but to serve their identity deficiencies.

Although greed has been responsible for abuse of economic power over the centuries, the moral failures of Enron and WorldCom and the other recent abuses of capitalism in the dot.com and telecommunications investment bubbles grew apace in the post-1950s American culture of decadence and self-absorption, the culture that incubated Ken Lay, Jeffrey Skilling, Andy Fastow, and Bernie Ebbers, as well as the investors they charmed with visions of never-ending profits.

If possessions largely define the personal self for our times, then there can never be too much money in our wallets or too many lines of credit at our immediate disposal. Our individual value pyramids are then easily subordinated to the Golden Calf of conspicuous consumption. By prosperity are we firmly pulled away from God toward Mammon. This cultural trend may make it harder for people in business to choose higher values and enlightened self-interest over immediate gratification of sensual desires.

CONCLUSION

The challenge of a moral capitalism, then, is to tip the balance of wealth creation toward humanity’s more noble possibilities and away from the dynamics of more brutish behavior. Chapter 2 begins a discussion of how values set in motion different kinds of capitalism.