CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Estimating is the art and science of using historical data, personal expertise, institutional memory, and the project scope statement to predict the resource expenditures, total cost, and duration of a project. A typical statement of project objectives will outline the attributes of a new physical deliverable, the details of performance enhancements to a system, or the purpose of a specific service. To estimate the project cost, the project manager must identify the various constituent physical elements and related activities necessary to meet the project objectives. Next, the project manager develops the estimate by summing the estimate of resources for these elements. Then, by extension, the project manager computes the elemental and project costs.

When the project is conceived, the estimate is extremely inaccurate because very little information is available about the expected deliverables, the project team, and the project environment. But, as the project evolves and more information becomes available, the estimate can be fine-tuned to a higher level of precision. Details of the objective, scope, quality, and desired delivery date are necessary for a comprehensive and accurate estimate. As these details become available, they in turn trigger enhancements in the work breakdown structure (WBS), the estimate, the schedule, and other planning documents. Further, the evolving planning documents could also include increasing details about the procedures that will be used in implementing the project.

The initial cost estimates of the elements and the project form the baseline budget for measuring the cost performance of the project during the implementation phase. This cost estimate, and therefore the budget, are initially very rough and inaccurate. When establishing the project budget on the basis of the project estimate, it is necessary to note whether the estimate was developed using a rough conceptual estimate technique or a detailed bottom-up estimate. If the budget was established during the early stages of project planning, the budget development process should allow some modification flexibility, primarily because early estimates are inaccurate.

Likewise, during the implementation phase, the project estimate serves as the base of reference for developing quantitative indicators of the project cost performance. Accordingly, depending on the accuracy and limitations of the estimate, appropriate contingencies, reserves, and flexibilities should also be incorporated into the budget. It is important to remember the degree of accuracy of the baseline estimate when making commitments, comparisons, and judgments during the budget development and project progress monitoring phases. In progressive organizations, the amount of budgeted funds for the project will go through several modifications as the details develop.

The credibility, accuracy, and completeness of the estimate are enhanced by the estimator’s skills in the areas of business, finance, engineering, technology, information systems, manufacturing, assembly, marketing, management, production planning, and all facets of project management activities. Since it is somewhat unrealistic to expect one person to have expertise in all these areas, organizations sometimes form estimating committees or estimating boards. The board members contribute their expertise from all technical disciplines impacted by the project such as business development, purchasing, contracting, financial management, and of course, project management.

The project’s cost estimate is derived by summing the resource expenditures and, consequently, the cost of the project’s individual component parts of the WBS. Likewise, with the hopeful expectation that estimating and scheduling processes use the same WBS, the estimate of the duration of the project’s component WBS elements is used in the development of the schedule network, which in turn formulates a time management structure. Therefore, there is an interdependent relationship between the project’s cost and the schedule. This interdependence must be taken into account during project implementation, when the changes in scope and specifications cause changes in the project’s cost and/or schedule. Furthermore, this relationship between cost and schedule must be continually reviewed as the project matures, detailed project plans are formulated, more definitive baselines are established, and finally, the inevitable tradeoffs are made during the implementation phase.

PROJECT SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES

The client’s needs and desires are communicated to the project personnel through documents such as the project’s charter, objectives, scope statement, and specifications. The terms requirements specifications and scope have been used interchangeably and sometimes differently depending on the industry in which the project is being implemented. Construction, industrial, and process projects refer to the description of the deliverable as scope and specifications. Scope refers to a broader expression of the client’s objectives while the term specifications refers to the detailed expression of the client’s objectives. Systems and software development projects often do not use the term scope while referring to deliverables, but they use the term requirements to describe the performance attributes of the projects, such as processing speed, error rate, database size, and the degree of friendliness of the deliverables. Systems and software projects use the term specifications to describe the attributes of the hardware. Hardware specifications for systems and software development projects might be either predetermined by the client as part of the project objectives or developed by the project team as one of the deliverable components.

Sometimes the quality of the project deliverable is not explicitly addressed as part of the definition of project objectives. Ironically, it is this issue of quality—independent of the volume of deliverables—that determines the usability of the product and the resulting satisfaction of the stakeholders. For the purposes of this book, quality and scope are treated collectively.

Project specifications are usually included in the contract documents if the project is an external project, and particularly if the contract is awarded on a lump sum basis. However, enlightened organizations develop specifications documents even for their internal projects. The objectives or specifications of an internal project are usually spelled out in the authorization memo that empowers the project manager to implement the project. The rationale for using specifications for an internal project is that, although an internal project does not involve a contract, it should have a set of well-defined scope and objectives, so that the delivery performance can be carefully monitored. The premise is that evaluation and monitoring of internal projects will become an ad-hoc activity if there are no focused objectives and, therefore, no detailed specifications.

The scope document includes the client’s wants and needs, the distinction being that “wants” are those items that would be desirable to have although not crucial to the success of the project, while “needs” are those items that are essential to the success and usability of the project deliverable. Again, this information will probably be very sketchy during the early stages of project evolution, and will be refined, clarified, and progressively elaborated as more information becomes available to the client and the project team.

Definition of project objectives involves detailing the project scope, attributes of the deliverables, acceptance tests, desired delivery date, expected budget, and team structure. When the client directs the activities of the project, the description of tools and techniques used in implementing the project are also included in the specifications document.

To some extent, the acceptance procedures and validation tests determine the physical quality and performance tolerances of the deliverable. Therefore, care should be taken to ensure that the tests reflect all the important operational facets of the product, and that these tests do not reflect frivolous features. In the same vein, the team should make every effort to craft the deliverable to the spirit of these tests and not necessarily to the letter of the tests, which might miss some important facet of the product. Due diligence on the part of the project team will promote client satisfaction, which is considered one of the most important indicators of a project’s success.

The desired delivery date signifies the date on which the client wishes to begin reaping the benefits of the deliverables, and, therefore, the most important date for the project’s schedule. Notwithstanding, for a variety of historical and operational reasons, several intermediate milestones are usually defined as part of project plans. Intermediate milestones are not crucial to the execution of the project, but the achievement of these milestones often signifies or verifies the expected pace of the project and the desired quality of the deliverables. The establishment of intermediate milestones can be in response to the needs and desires of the client, the collective project team, individual team members, or the stakeholders.

A carefully drafted project objective document is essential to the project’s success. The objective statement is the focal point and the definitive reference source for managing the triple constraints of the project during the implementation phase. Project procedures must include instructions on how to treat the project objective statement as a living document to be enhanced continually, albeit the current version of this statement will be used as a base of performance reference through the life of the project. Project management procedures must highlight uniform and consistent guidelines for the development of, and making modifications to, the baseline project objectives and specifications.

Project planning documents must include details of processes, procedures, and methodologies that will be used for monitoring the effectiveness and efficiency of the project team in implementing the project deliverable. Since the characteristics of the team can have subtle but significant impact on the project’s success, the characteristics of the project team must be outlined in planning the physical deliverable of the project. Team attributes that must be addressed are the skill of team members, the administrative affiliation of team members, and the time spent on other duties during the project at hand. Further, project management activities dealing with team formation and team charter must be well defined and planned during the very early stages.

Particularly in external projects, the major items of equipment used to craft the project deliverable and to test its important attributes should be included. For external projects, the number of subcontractors and the overall contracting strategy must be carefully evaluated in the light of the best interests of the project and its business plan, and not just on the basis of the lowest initial cost. Contracting strategy will impact the communication pattern among project stakeholders, and will subtly affect project performance.

The fee structure of a contractor can profoundly affect the total project cost. Therefore, a careful analysis of direct costs, indirect costs, overhead, and the contractor’s profit margin is advisable, particularly if the contract is being awarded on a cost-plus basis.

A review of marginal or failed projects shows that the vast majority suffered from lack of detailed planning, or casual and ad-hoc procedures for managing the project’s changes. Conversely, the literature shows that organizations that encourage detailed planning of projects experience far better financial growth when compared to organizations that do not. Finally, data support the concept that organizations that employ competent project management professionals and consistent project management procedures tend to produce more successful projects.1,2

ORGANIZATIONAL OBJECTIVES

Projects are usually undertaken in response to a set of goals that is identified to achieve organizational objectives. The most common categories of organizational objectives include operating necessity, competitive necessity, or innovative ventures. Therefore, as a prelude to project selection and initiation, organizational priorities must be clearly identified and clarified.

One of the important components of a project definition document is the rationale statement detailing how the project investment is reconciled with organizational strategic goals and investment policies. Further, with innovative and creative crafting of project objectives, it is possible for a project management team to develop alternative options in achieving the same organizational goal. Finally, a project should be considered for authorization after considering individuals’ current workloads, the divisions’ operational obligations, and the parent organization’s current financial obligations.

The planning documents for each project must include all available data on the project’s sponsor, objectives, and deadline. The project’s business plan must clearly articulate the reasons for initiating this project and the expected benefits of the project’s deliverable. Further, in many ways, implicit or explicit corporate support for the project determines the organizational viability and the project’s importance. A signal that there is insufficient administrative support for the project is that senior management is not willing to sponsor it. To satisfy this requirement, key executives and major stakeholders sponsoring the project must be identified in project charter documents.

To reconcile the project costs with the corporate investment strategies, each project must have a business objective, which serves as the foundation for the project’s investment proposal. The document containing the project objectives and investment strategies is called a business case or a business plan. The business plan should provide ample information on the project deliverable’s utility, which will then be used to determine whether or not the project should be funded for implementation. It also should provide details of all costs, benefits, and risks associated with the delivery of the proposed project.

To meet this mandate, the business plan must provide a detailed description of the problem, need, or opportunity to which the project is expected to respond. Then, the alternative projects that respond to the same opportunity must be highlighted in terms of expected deliverables, conceptual estimate, preliminary schedule, and a quantified list of benefits and risks.

The business plan for a specific organizational objective may be related to several alternative projects. These projects offer slightly different deliverables and yet they all would achieve the same general business objectives. In some cases, one project might impact two separate organizational strategies. Therefore, in a proactive and dynamic organization, it is normal to have a large portfolio of possible projects. However, funding limitations usually preclude implementation of all these projects. Consequently, a formalized project ranking and selection process must be developed to identify the projects with the most impact on the organizational needs at hand, at the lowest possible funding, and with optimized values of other issues important to the organization.

PROJECT SELECTION

Selection of projects for implementation must be performed in consideration of the organization’s needs and wants, corporate strategic plans, realistic expectations for sophistication of the deliverables, success attributes of the project, and the constraints for the project’s success. To make consistent and logical decisions in prioritizing and selecting projects, a company-specific process of evaluating projects must be established.

Ranking of projects is most commonly conducted with the use of an index, sometimes called a metric, or a group of indices called a model. In general, models are easy-to-use characterizations of operations, organizations, and relationships. The models range from very simple to very complex, although all models, even the very sophisticated ones, are only a partial representation of the reality that they attempt to portray.

Although models are very useful as aids in the decision-making process, they do not fully duplicate all facets of the real world. On the other hand, with this focused feature of models in mind, models can be exploited to purge extraneous elements of a problem and to highlight the important elements of the issues surrounding project implementation. The objective of the project selection process is to rank the projects for implementation in the organization’s best interest. The selection process, therefore, would use a model that is specifically formulated to optimize parameters such as organizational goals, project cost, project duration, and the anticipated attributes of the project deliverable.

The numeric results of the model must always be tempered by the experience and professional expertise of the organizational entity charged with managing the project portfolio. Ideally, this entity is the project management office, although the function might be performed by an ad-hoc, or standing, team designated by upper management. The project portfolio management group is expected to make a judgment on project viability using information generated by the model, and in consideration of the model’s limitations and constraints and/or its constituent indices. This judgment, however, will be partly predicated on the quantified rankings provided by the models or indices.

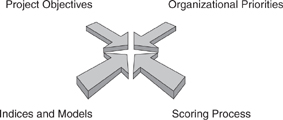

During a typical project selection process, it is necessary to identify organizational priorities for projects, establish metrics to evaluate project objectives in the light of these priorities, and formulate company-specific scoring schemas for the project ranking process. There are four sets of basic elements for the selection process: organizational priorities, project objectives, the selection model, and the ranking process (see Figure 1-1).

Indices used for project selection tend to fall into two major categories. The first category includes quantitative indices that are generally based on financial characteristics such as:

Total cost

Cash flow demand

FIGURE 1-1 Project Selection

Cost-benefit ratio

Payback period

Average internal rate of return

Net present value.

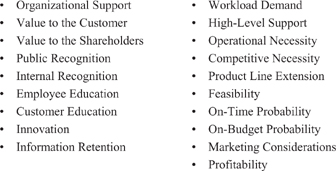

The second category includes qualitative indices that are intended to measure subjective issues, such as operational necessity, competitive necessity, product line extension, market constraints, desirability, recognition, and success (see Figure 1-2).

A project selection model is very organization-specific and should use a customized combination of indices to satisfy the organizational project selection objectives. Since models depend on numeric input from the indices, even subjective indices ultimately will have to be quantified. Accordingly, a measure of refinement will be added to the selection process if the quantification of the subjective model indices is based on consistent and organization-specific procedures. Then, using the project data, organizational priorities, customized model, and a consistent scoring process, it is possible to systematically, and in a formalized fashion, rank the prospective projects.

FIGURE 1-2 Qualitative Indices

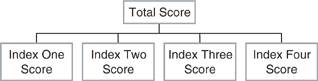

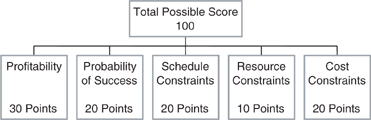

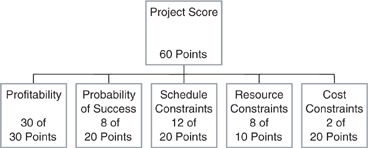

Figure 1-3 shows a graphical depiction of a selection model that is composed of four indices. The simple summation or weighted summation of the results of the indices is used to compute the rating of the project by this model. Figure 1-4 shows a sample of a customized model. The possible total points for a project are 100 and, therefore, prospective projects can be compared on the basis of the total score yielded by this model. The importance of each of the indices in this model is signified by the points assigned to each index, which has been customized for a particular organization. The relative importance of these indices is reflected by how many maximum possible points are assigned to each index.

To extend the illustration a bit further, a hypothetical project might receive a total score of 60 points on the basis of the scoring that the project received on individual indices that were identified and ranked specifically for that organization (see Figure 1-5). It should be noted that the score of an individual project is not as important as the relative scores of several projects that were ranked using the same model and the same rating process.

When conducting project comparisons, it is useful and logical to normalize the base of reference. One of the more convenient techniques is to use the direct cost as the base of reference for the prospective projects. Compartmentalizing the direct cost of the project from other elements has the advantage of developing a project estimate strictly from the standpoint of the level of effort. Other elements such as indirect costs, overhead, and return on investment are important values; however, since they tend to be somewhat variable with organizational entity and time, they might add unnecessary inaccuracy to the project selection process.

FIGURE 1-3 Project Selection Model

FIGURE 1-4 100 Point Project Scoring System—Maximum Points Possible

FIGURE 1-5 100 Point Project Scording System—Total Project Score

Estimating is a very inexact science during the early periods of a project’s life. Ironically, the very early estimates of a project become one of the critical factors in determining whether the project reaches the next stage by virtue of allocation of funds. Naturally, the accuracy of any given estimate is enhanced by a detailed and focused set of project objectives. Organizational objectives and deliverable expectations also play important roles in selecting a project for implementation. A formalized project selection procedure will include a selection model consisting of several quantified indices that reflect the project attributes in the light of the organizational priorities and objectives.

NOTES

1. C.W. Ibbs and Y.H. Kwak, The Benefits of Project Management—Financial and Organizational Rewards to Corporations (Sylva, NC: PMI® Publications, 1997).

2. M.R. Vigder and A.W. Kark, Software Cost Estimation and Control (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: National Research Council of Canada, February 1994).