Servant Leadership in Action

Chapter 1

What Is Servant Leadership?

KEN BLANCHARD

Okay, let’s get started. As Julie Andrews sang in The Sound of Music, “Let’s start at the very beginning. . . .” What is servant leadership all about? In this essay, I’ll give you my thoughts. —KB

WHEN PEOPLE HEAR the phrase servant leadership, they are often confused. Their assumption is that it means managers should be working for their people, who would decide what to do, when to do it, where to do it, and how to do it. If that’s what servant leadership is all about, it doesn’t sound like leadership to them at all. It sounds more like the inmates running the prison, or trying to please everyone.

The problem is that these folks don’t understand leadership—much less servant leadership.

1

They think you can’t lead and serve at the same time. Yet you can, if you understand that there are two parts to servant leadership:

• a visionary/direction, or strategic, role—the leadership aspect of servant leadership; and

• an implementation, or operational, role—the servant aspect of servant leadership.

Some people say that leadership is really the visionary/direction role—doing the right thing—and management is the implementation role—doing things right. Rather than getting caught in the leadership vs. management debate, let’s think of these both as leadership roles.

In this book, we focus on leadership as an influence process in which you try to help people accomplish goals. All good leadership starts with a visionary role, as Jesse Stoner and I explain in our book Full Steam Ahead!

2

This involves not only goal setting, but also establishing a compelling vision that tells you who you are (your purpose), where you’re going (your picture of the future), and what will guide your journey (your values). In other words, leadership starts with a sense of direction.

I love the saying “a river without banks is a large puddle.”

3

The banks permit the river to flow; they give direction to the river. Leadership is about going somewhere; it’s not about wandering around aimlessly. If people don’t have a compelling vision to serve, the only thing they have to serve is their own self-interest.

Walt Disney started his theme parks with a clear purpose. He said, “We’re in the happiness business.” That is very different from being in the theme park business. Being in the happiness business helps cast members (employees) understand their primary role in the company.

When it comes to a purpose statement, too many organizations, if they have one, make it too complicated. I’ll never forget talking to all of the key managers of a major bank. Prior to my speech, I asked them to send me their purpose statement if they had one, which they did. When I got up in front of the group, I told them how much I appreciated their sending me their purpose statement. “Ever since I got it, I’ve slept so much better. Why? Because I put it next to my bed and if I couldn’t sleep at night I would read it.” The purpose statement droned on and on. I said, “If I were working with you, I would hope you would say ‘We are in the financial peace of mind business—if people give us money, we will protect it and even grow it.’” Everyone laughed because they knew that would be something that all their people could easily share and follow.

Once you have a clear purpose that tells you who you are, you need to develop a picture of the future so that everyone knows where you are going. Walt Disney’s picture of the future was expressed in the charge he gave every cast member: “Keep the same smile on people’s faces when they leave the park as when they entered.” Disney didn’t care whether a guest was in the park two hours or ten hours. He just wanted to keep them smiling. After all, they were in the happiness business. Your picture of the future should focus on the end results.

The final aspect of a compelling vision involves your values, which are there to guide your journey. Values provide guidelines for how you should proceed as you pursue your purpose and picture of the future. They answer the questions “What do I want to live by?” and “How?” They need to be clearly described so that you know exactly what behaviors demonstrate those values as being lived.

The Disney theme parks have four rank-ordered values: safety, courtesy, the show, and efficiency. Why is safety the highest ranked value? Walt Disney knew that if a guest were to be carried out of one of his parks on a stretcher, that person would not have the same smile on their face leaving the park that they had when they entered.

The second-ranked value, courtesy, is all about the friendly attitude you expect at a Disney theme park. Why is it important to know that it’s the number-two value? Suppose one of the Disney cast members is answering a guest question in a friendly, courteous manner, and he hears a scream that’s not coming from a roller coaster. If that cast member wants to act according to the park’s rank-ordered values, he will excuse himself as quickly and politely as possible and race toward the scream. Why? Because the number-one value just called. If the values were not rank-ordered and the cast member was enjoying the interaction with the guest, he might say, “They’re always yelling at the park,” and not move in the direction of the scream. Later, somebody could come to that cast member and say, “You were the closest to the scream. Why didn’t you move?” The response could be, “I was dealing with our courtesy value.”

Life is a series of value conflicts. There will be times when you can’t act on two values at the same time. I have a hunch that’s why Walt Disney put efficiency—running a profitable business—as the fourth-ranked value. He wanted to make clear they would do nothing to save money that would put people in danger, nor do a major downsizing in the park that impacted in a negative way their courtesy value.

Once an organization has a compelling vision, they can set goals and define strategic initiatives that suggest what people should be focusing on right now. With a compelling vision, these goals and strategic initiatives take on more meaning and therefore are not seen as a threat, but as part of the bigger picture.

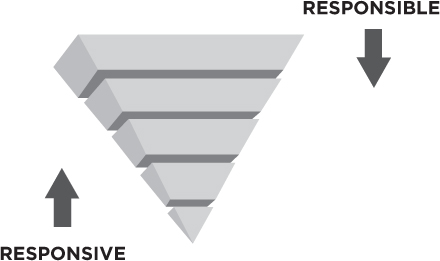

The traditional hierarchical pyramid (see Figure 1.1) is effective for the leadership aspect of servant leadership. Kids look to their parents, players look to their coaches, and people look to their organizational leaders for vision and direction. While these leaders should involve experienced people in shaping direction, the ultimate responsibility remains with the leaders themselves and cannot be delegated to others.

Once people are clear on where they are going, the leader’s role shifts to a service mindset for the task of implementation—the second aspect of servant leadership. The question now is: How do we live according to the vision and accomplish the established goals? Implementation is where the servant aspect of servant leadership comes into play.

Figure 1.1 Visionary/leadership role

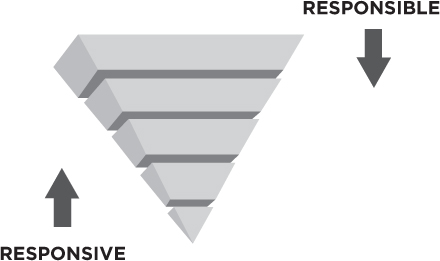

Most organizations and leaders get into trouble in the implementation phase of the leadership process. With self-serving leaders at the helm, the traditional hierarchical pyramid is kept alive and well. When that happens, who do people think they work for? The people above them. The minute you think you work for the person above you for implementation, you are assuming that person—your boss—is responsible and your job is being responsive to that boss and to his or her whims or wishes. Now “boss watching” becomes a popular sport and people get promoted on their upward-influencing skills. As a result, all the energy of the organization is moving up the hierarchy, away from customers and the frontline folks who are closest to the action. What you get is a duck pond. When there is a conflict between what the customers want and what the boss wants, the boss wins. You have people quacking like ducks: “It’s our policy.” “I just work here.” “Would you like me to get my supervisor?” Servant leaders know how to correct this situation by philosophically turning the traditional hierarchical pyramid upside down when it comes to implementation (see Figure 1.2).

When that happens, who is at the top of the organization? The customer contact people. Who is really at the top of the organization? The customers. Who is at the bottom now? The “top” management. As a result, who works for whom when it comes to implementation? You, the leader, work for your people. This one change, although it seems minor, makes a major difference. The difference is between who is responsible and who is responsive.

When you turn the organizational pyramid upside down, rather than your people being responsive to you, they become responsible—able to respond—and your job as the leader/manager is to be responsive to your people. This creates a very different environment for implementation. If you work for your people as servant leaders do, what is the purpose of being a manager? To help your people become eagles rather than ducks and soar above the crowd—accomplishing goals, solving problems, and living according to the vision.

4

Figure 1.2 Implementation/servant role

As a customer, you can always tell an organization that is run by a self-serving leader. Why? Because if you have a problem and go to a frontline customer contact person to solve it, you are talking to a duck. They say, “It’s our policy,” quack quack; “I didn’t make the rules,” quack quack; “Do you want to talk to my supervisor?” quack quack.

Several years ago, a friend of mine had an experience in a department store that illustrates this point well. While shopping, he realized he needed to talk to his wife but he had left his cell phone at home. He asked a salesperson in the men’s department if he could use the telephone.

“No,” the salesperson said.

My friend replied, “You have to be kidding me. I can always use the phone at Nordstrom.”

The salesperson said, “Look, buddy, they don’t let me use the phone here. Why should I let you?”

That certainly isn’t what servant leadership is all about. Who do you think that salesperson worked for—a duck or an eagle? Obviously, a supervisory duck. Who does that duck work for? Another duck, who works for another duck. And who sits at the top of the organization? The head mallard—a great big duck. If the salesperson had worked for an eagle, both he and the customer would have been able to use the phone!

Now contrast that with the eagle experience one of my colleagues had when he went to Nordstrom one day to get some perfume for his wife. The woman behind the counter said, “I’m sorry; we don’t sell that perfume in our store. But I know where I can get it in the mall. How long will you be in our store?”

“About 30 minutes,” my colleague said.

“Fine. I’ll go get it, bring it back, gift wrap it, and have it ready for you when you leave.”

This woman left Nordstrom, went to another store, got the perfume my colleague wanted, came back to Nordstrom, and gift wrapped it. You know what she charged him? The same price she had paid at the other store. So Nordstrom didn’t make any money on the deal, but what did they make? A raving fan customer.

To me, servant leadership is the only way to guarantee great relationships and results. That became even clearer to me when I realized that the two leadership approaches I am best known for around the world—The One Minute Manager® and Situational Leadership® II (SLII®)—are both examples of servant leadership in action.

After all, what’s the First Secret of The One Minute Manager? One Minute Goals. All good performance starts with clear goals—which is clearly part of the leadership aspect of servant leadership. Once people are clear on goals, an effective One Minute Manager wanders around and tries to catch people doing something right so that they can deliver a One Minute Praising—the Second Secret. If the person is doing something wrong or not performing as well as agreed upon, a One Minute Re-Direct is appropriate—the Third Secret. When effective One Minute Managers deliver praisings and redirects, they are engaging in the servant aspect of servant leadership—they are working for their people to help them win—accomplish their goals.

5

Situational Leadership® II

6

also has three aspects that generate both great relationships and results: goal setting, diagnosis, and matching. Once clear goals are set, an effective SLII leader works with their direct report to diagnose the direct report’s development level—competence and commitment—on each specific goal. Together they then determine the appropriate leadership style—the amount of directive and supportive behavior—that will match the person’s development level on each goal so that the manager can help them accomplish their goals. The key here, in the servant aspect of servant leadership, is for managers to remember they must use different strokes for different folks and also different strokes for the same folks, depending on the goal and the person’s development level.

Why are the concepts of The One Minute Manager and SLII so widely used around the world? I think it’s because they are clear examples of servant leadership in action. Both concepts recognize that vision and direction—the leadership aspect of servant leadership—is the responsibility of the traditional hierarchy. The servant aspect of servant leadership is all about turning the hierarchy upside down and helping everyone throughout the organization develop great relationships, get great results, and, eventually, delight their customers. That’s what servant leadership is all about.

Notes

1. Ken Blanchard et al., Leading at a Higher Level (Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press, 2006, 2010). See chapter 14 for a more extensive discussion of what servant leadership is all about.

2. See Ken Blanchard and Jesse Stoner, Full Steam Ahead: Unleash the Power of Vision in Your Company and Your Life (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003, 2011) for more about the visionary role of leadership.

3. This expression was coined by Alan Randolph. See Ken Blanchard, John Carlos, and Alan Randolph, Empowerment Takes More Than a Minute (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1996).

4. Ken first heard this distinction between ducks and eagles from author and legendary personal growth guru Wayne Dyer.

5. Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson, The One Minute Manager (New York: William Morrow, 1982, 2003). See also their The New One Minute Manager (New York: William Morrow, 2015).

6. Ken Blanchard first developed Situational Leadership® with Paul Hersey in the late 1960s. It was in the early 1980s that Ken and founding associates of The Ken Blanchard Companies—Margie Blanchard, Don Carew, Eunice Parisi-Carew, Fred Finch, Laurie Hawkins, Drea Zigarmi, and Patricia Zigarmi—created Situational Leadership® II. The best description of this thinking can be found in Ken Blanchard, Patricia Zigarmi, and Drea Zigarmi, Leadership and the One Minute Manager (New York: William Morrow, 1985, 2013).