Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety

Defining the Path to Inclusion and Innovation

Timothy R. Clark (Author) | Larry Herron (Narrated by)

Publication date: 03/03/2020

This book is the first practical, hands-on guide that shows how leaders can build psychological safety in their organizations, creating an environment where employees feel included, fully engaged, and encouraged to contribute their best efforts and ideas.

Fear has a profoundly negative impact on engagement, learning efficacy, productivity, and innovation, but until now there has been a lack of practical information on how to make employees feel safe about speaking up and contributing. Timothy Clark, a social scientist and an organizational consultant, provides a framework to move people through successive stages of psychological safety. The first stage is member safety-the team accepts you and grants you shared identity. Learner safety, the second stage, indicates that you feel safe to ask questions, experiment, and even make mistakes. Next is the third stage of contributor safety, where you feel comfortable participating as an active and full-fledged member of the team. Finally, the fourth stage of challenger safety allows you to take on the status quo without repercussion, reprisal, or the risk of tarnishing your personal standing and reputation. This is a blueprint for how any leader can build positive, supportive, and encouraging cultures in any setting.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

This book is the first practical, hands-on guide that shows how leaders can build psychological safety in their organizations, creating an environment where employees feel included, fully engaged, and encouraged to contribute their best efforts and ideas.

Fear has a profoundly negative impact on engagement, learning efficacy, productivity, and innovation, but until now there has been a lack of practical information on how to make employees feel safe about speaking up and contributing. Timothy Clark, a social scientist and an organizational consultant, provides a framework to move people through successive stages of psychological safety. The first stage is member safety-the team accepts you and grants you shared identity. Learner safety, the second stage, indicates that you feel safe to ask questions, experiment, and even make mistakes. Next is the third stage of contributor safety, where you feel comfortable participating as an active and full-fledged member of the team. Finally, the fourth stage of challenger safety allows you to take on the status quo without repercussion, reprisal, or the risk of tarnishing your personal standing and reputation. This is a blueprint for how any leader can build positive, supportive, and encouraging cultures in any setting.

STAGE 1

Inclusion Safety

Our ability to reach unity in diversity will be the beauty and the test of our civilization.

—Mahatma Gandhi

Figure 5. Entering the path to inclusion and innovation

Diversity is a fact. Inclusion is a choice.

But not just any choice.

Key concept: The choice to include another human being activates our humanity.

As the first stage of psychological safety, inclusion safety is, in its purest sense, nothing more than species-based acceptance (figure 5, previous page). If you have flesh and blood, we accept you. Profoundly simple in concept, devilishly difficult in practice, we learn it in kindergarten and unlearn it later. A mere 36 percent of business professionals today believe their companies foster an inclusive culture. 1

I remember talking to my son, Ben, after his first day of kindergarten:

“How did you like your first day of kindergarten, Ben?” I asked.

“It was fun, Dad.”

“Are you excited to go to school tomorrow?”

“Yeah, I’m excited.”

“Is Mom going to take you to school again tomorrow?”

“No, I’m going to walk.”

“Do you have anyone to walk with?”

“No, Dad, I’ll just walk by myself, but if anyone wants to walk with me, they can.”

I’ll never forget that tender exchange. It’s a reflection of the un-corrupted, inclusive nature of children.

Key concept: We include naturally in childhood and exclude unnaturally in adulthood.

Out of our flaws and insecurities, we model and reinforce exclusion to those around us. But it doesn’t have to be that way. After living with the Navajo for a few years, my family moved to Los Angeles and then finally settled into a middle-class neighborhood in the San Francisco Bay Area. I remember feeling uprooted and lost as a boy. Bored, lonely, and battling a little resentment, I sat on the porch one day when a kid from the neighborhood rode up on his bike. He walked over and, without any hesitation, announced, “Hi, I’m Kenny.” In no time, we were riding our bikes together, eating kumquats, and catching alligator lizards. The young man who befriended me and extended inclusion safety so confidently at age ten is now Pastor Kenny Luck, the men’s pastor at the Camelback Church in Lake Forest, California.

Not everyone is born with Kenny’s confidence and sense of concern, but the basic decision to include or exclude is not about skill or personality, although those things can enhance your ability to include. It’s more about intent than technique. You can’t legislate it, regulate it, train it, measure it, or gimmick it into existence. It doesn’t answer to those forces. It’s an act of will that flows from the empire of the heart. If there’s no psychological safety, there’s no inclusion.

Key concept: Including another human being should be an act of prejudgment based on that person’s worth, not an act of judgment based on that person’s worthiness.

Our children memorized passages from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” in school. I can still hear them recite the line, “I look to a day when people will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” The theologian Reinhold Niebuhr made a similar observation when he said, “We are admonished in scripture to judge men by their fruits, not by their roots.” 2

Before we judge others as less exalted, please note that the Reverend King and Pastor Niebuhr are talking about worthiness of character. My point is that worth comes first, worthiness comes second. Inclusion safety is not about worthiness. It’s about treating people like people. It’s the act of extending fellowship, membership, association, and connection—agnostic of rank, status, gender, race, appearance, intelligence, education, beliefs, values, politics, habits, traditions, language, customs, history, or any other defining characteristic. Inclusion marks passage into civilization. If we can’t do that as a starting point, we’re not being true to what Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature.” Withholding inclusion safety is a sign that we’re engaged in a fight with our own willful blindness. We’re self-medicating with enchanting tales about our distinctiveness and superiority. If it’s a mild case of snobbery, that may be easy to dismiss. But if it’s a more severe case of narcissistic supremacy, that’s a bigger problem. And then there’s everything in between.

In our social units, we should create an environment of inclusion before we begin to think about judgments at all. Worth precedes worthiness. There’s a time and a place to judge worthiness, but when you allow someone to cross the threshold of inclusion, there’s no litmus test. We’re not weighing your character in the balance to see if you’re found wanting. To be deserving of inclusion has nothing to do with your personality, virtues, or abilities; nothing to do with your gender, race, ethnicity, education or any other demographic variable that defines you. There are, at this level, no disqualifications, except one—the threat of harm.

The only reciprocation requirement in this unwritten social contract is the mutual exchange of respect and permission to belong. That exchange is unenforceable by law. There are, of course, laws against discrimination, but in a thousand ways we can still informally persecute each other.

Let me give you an example of A/B testing for inclusion safety. I have two cars. One is old and rusty, has 315,000 miles on the odometer, and a resale value of $375. The other is a black sports sedan. When I take in my sedan for service, the attendant is highly responsive. When I take my rust bucket, the attendant can be mildly disdainful. In both cases, the car is the lead indicator of my social status, and people grant or withhold inclusion safety based on my car, the artifact in which I sit. Some days I’m politely ignored, some days solicitously attended to. That’s how sensitive people are to these indicators because we scramble for status like apes for nuts.

Key questions: Do you treat people that you consider of lower status differently than those of higher status? If so, why?

What should it take to qualify for inclusion safety? Two things: Be human and be harmless. If you meet both criteria, you qualify. If you meet only one, you don’t. The great African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass made the definitive statement about inclusion safety when he said, “I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity.” That statement can apply to any characteristic. When we extend inclusion safety to each other, we subordinate our differences to invoke a more important binding characteristic—our common humanity.

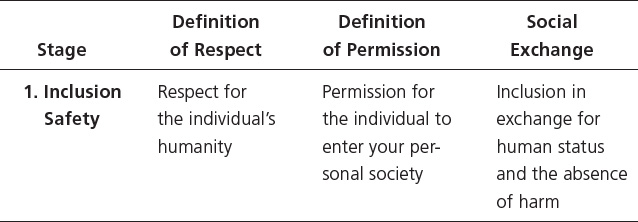

Table 1 defines respect and permission in the first stage of psychological safety. The definition of respect in this stage is simply respect for the individual’s humanity. Permission in this stage is the permission you give another to enter your personal society and interact with you as a human being. Finally, the social exchange is one in which we trade inclusion for human status, provided we don’t threaten each other with harm.

Table 1 Stage 1 Inclusion Safety

Despite knowing we should extend inclusion safety to everyone, we have become very skilled at chasing each other to the margins and patrolling the boundaries. We splinter, segment, and stratify the human family. Sometimes, we extend partial or conditional inclusion safety. Sometimes we revoke or withhold it.

Key concept: Instead of granting inclusion safety based on human status, we tend to judge another person’s worthiness based on indicators like appearance, social status, or material possessions, when those indicators have nothing to do with worth.

Kimchi and Our Common Humanity

When I was in graduate school, I had the opportunity to do research at the Seoul National University in Korea as a Fulbright scholar. The university offered me a place at its Social Science Research Center. The day I arrived, Professor Ahn Chung Si greeted me warmly and took me around the center to meet the staff and other researchers. My initial apprehension was replaced with a sense of inclusion when two Korean graduate students asked me to go to lunch. I was the different one, the stranger, the alien, the one that didn’t fit in. But I was not the odd person out. Holding my bowl of rice dumpling soup, I sat down at one of the tables in the cafeteria and was soon greeting other students and faculty. With some hesitation, a student sitting next to me handed me a bowl of kimchi. That was the beginning of an extraordinary experience with inclusion safety.

True, I was a novelty, but I hasten to say that inclusion safety is not simply the expression of hospitality. You can be polite and not mean it. That kind of surface acting is a disingenuous way of abiding by common rules of decency and decorum. But these students were not only kind and helpful on my first day, which is easy to do. They were also kind and helpful on my thirtieth day and my sixtieth day and so on. I was clearly outside their social group and overstayed the normal expiration date for standard-protocol, obligatory, respectful treatment. But after weeks and weeks of long days at the center, they never revoked the inclusion safety they first extended. It was real.

Key questions: In the arc of every life are times when inclusion safety makes all the difference, when someone reaches out to include you at a vulnerable time. When did this happen to you? What impact did it have on your life? Are you paying it forward?

Let’s put this in historical context. South Korea is considered the world’s most neo-Confucian society, historically embracing status hierarchy, inequality, and inherent discrimination as values. Human rights have a short history, but have in recent years been acknowledged as a matter of political expediency, not through some religious or philosophical sense of natural law, inalienability, or God-invested entitlement. In this society, rights are more instrumental than moral, more negotiated than inviolate, more legislated than guaranteed or absolute. Confucianism lacks rational, legal, or moral grounds for inclusion, but rather emphasizes loyalty, devotion, allegiance, and compliance to authority in the promotion of group harmony and stability.

What does all of that mean? It means I’m an outsider. There’s no natural place for me in Korean society or hierarchy. And yet my Korean friends included me in a way that superseded their neo-Confucian tradition. They suspended the normal terms of engagement, giving precedence to a higher principle of humanity. Rather than focus on differences, they emphasized common fellowship. 3 Was I now Korean? Did they grant me full social and cultural membership? No. They extended inclusion safety, but on what basis? Was it religious, ethnic, socioeconomic, geographic, cultural, political, legal? None of the above. It was based on a supernal, primordial human connection that overcame our separatism and penetrated to membership in a universal family.

Key question: To create inclusion safety, it helps to understand cultural differences, but you don’t need to be an expert in those differences, just sensitive to and appreciative of them. How do you acknowledge and show sensitivity and appreciation for the cultural differences that exist on your team?

Hardening the Concept of Equality

The philosopher John Rawls reminds us of this fundamental truth: “Institutions are just when no arbitrary distinctions are made between persons in the assigning of basic rights and duties.” 5 To exclude a member of a social unit based on conscious or unconscious bias is exactly that, an arbitrary distinction. These must be removed, as Rawls says, to “build an enduring system of mutual cooperation.” 6

There will always be differences, but there mustn’t be barriers. There will always be majorities and minorities, but we should never attempt to deracinate each other until we melt into a homogenous lot. Our differences define us.

Some would object on grounds that we don’t know each other. So how can we accept, include, tolerate, and connect with strangers? And in fact, research shows that the key drivers of psychological safety include familiarity among team members and the quality of those relationships based on prior interactions. 7 To extend inclusion safety is not to extend mature, developed feelings of affection. Your feelings can only be expectant and assumptive, but they can still be real. Xenophobic arguments are born of ignorance, fear, jealousy, or a dishonest desire for superiority.

Key concept: God may have made us of different clay, but there are no grounds to say that your clay is better than mine.

Inclusion safety is not earned but owed. Every human has title to it as a nonnegotiable right. In fact, we can’t sustain civilization without it. 8 We hunger for and deserve dignity and esteem from each other and unavoidably practice morality when we extend or withhold inclusion safety. If there’s no threat of harm, we should give it without a value judgment. As the basic glue of human society, inclusion safety offers the comforting assurance that you matter. If you’re a leader and want your people to perform, you must internalize the universal truth that people want, need, and deserve validation. Inclusion safety requires that we condemn negative bias, arbitrary distinction, or destructive prejudice that refuses to acknowledge our equal worth and the obligation of equal treatment.

If everyone deserves inclusion, if we’re all entitled to fellowship and connection, if we have the right to civil and respectful interactions, if the reciprocation of courtesy defines us as a species—we have an obligation to demolish nativism and ethnocentrism. Nations, communities, and organizations aren’t the only offenders. 9 We see alienation within families, as individuals shun, banish, and relegate each other to subordinate status. We see parents and children who neglect or harm each other. And then there are the glorious triumphs when we get it right, when we extend the hand of fellowship and are blessed in that moment with the fulfillment of real human connection.

Granting, Withholding, and Revoking Inclusion Safety

After graduating from high school, I took an athletic scholarship to play Division I football at Brigham Young University. Arriving on campus a month early to begin summer training camp, all freshmen players were assigned to live in the same dormitory near the practice facilities. Here was a group of ethnically and culturally diverse young men thrust into a highly structured environment, a para-military boot camp, characterized by sudden and complete immersion.

We surrendered our personal freedom and space, and from that moment would eat, sleep, shower, and sweat together. The machinery of the football regimen dictated every aspect of our daily lives. My teammates represented three primary racial groups—black, white, and Polynesian. But this was nothing new. Despite our coming together from all parts of the country, our racial composition was familiar to most of us. We had been deeply socialized in the ethnically diverse subculture of American football and understood its norms and meritocracy.

The task was to form a new society, one that would organize itself on both Darwinian and communitarian principles. A football team competes with other teams, but its players compete with each other. While the external rivalry was institutional, the internal rivalry was personal. You might be competing with the guy sleeping in the bed next to you. We played a zero-sum, finite game. Introducing the element of competition changes the dynamics of a society and the terms of engagement for granting or withholding inclusion safety. The prevailing norms were at the same time collegial and adversarial, and that duality was maintained throughout the experience. Your teammate could be friend and foe.

The nature of the team-sport environment accelerates the development of familiarity, which is massively important in the formation of psychological safety. As sociometric research from the MIT Human Dynamics Lab attests, the faster and deeper you get to know each other, the more effectively you can work together. 10 More contact and context tend to create more empathy.

On the first day, we bonded slowly, knowing that we would begin practicing and competing the following day. That reality made the collegial and adversarial forces collide. As a result, our initial greetings were warm with fellow players who didn’t play our same positions, and chilled with those who did. Every player arrived dripping with honors and recognition, so bluster and bravado were signs of insecurity and a clear signal that a player wasn’t as good as advertised.

In what is akin to a modern-day blood sport, you can’t carry on a rhetorical career for very long. Performance does the talking. Football was our common aspiration, but the internal competition was a divisive element. We were formally admitted members of the team but extending inclusion safety to each other was an individual matter. Ironically, we admitted or refused to admit each other in the act of joining the society ourselves.

Instead of fusing into a cohesive group, we balkanized into smaller groups based on race or geography. And then of course there were the offensive linemen, who bonded into a unique fraternity of sensitive, industrial-size humans and shut the gates behind them. I, on the other hand, played defensive tackle, where that sort of bonding would violate our gladiator subculture. After a week of what MIT’s Edgar Schein would call “spontaneous interaction,” you could see norms starting to form. 11 But a week later, the upperclassmen arrived, and our organic society was swallowed up by the larger machine.

When you join an existing organization, as I came to the football team, you inherit a cultural legacy based on perpetuated norms. Unless you’re forming a new social collective, you don’t start clean. In our case, we freshmen started clean and erected a temporary society that was then abruptly dismantled. When the rest of the team arrived, it was as if the mothership had landed with its cargo of artifacts, habits, customs, mores, and distribution of power. Here came the unyielding orthodoxy and way of doing things, all modeled and reinforced by the coaching staff. Punctuality rule? Enforced. Dress code rule? Not enforced. Respect rule? Enforced. No profanity rule? Not enforced. And so on. As we moved into the regular season, inclusion safety gradually emerged. The internal rivalries settled, and we came together.

Now came the inclusion safety lesson of a lifetime: Halfway into the season, I sustained a serious injury. When the diagnosis came back that I had severely damaged my ankle and needed surgery, I experienced a sudden and dramatic change in status. My position coach revoked inclusion safety through a silent campaign of neglect. I was injured and therefore unable to contribute to the team. To him I was now invisible. He had extended conditional inclusion safety to me, not based on my worth as a human being, but rather on my worthiness as a player. The moment I got hurt and was no longer useful to the team, he withdrew his fellowship through subtle and unmistakable indifference. That indifference stung. As I quickly learned, inclusion safety, once built, is fragile, delicate, and impermanent.

Key concept: In any social unit, inclusion safety can be granted, withheld, revoked, or partially or conditionally granted.

Soothing Ourselves with Junk Theories of Superiority

Theories have consequences. Too often we have run our societies on intellectually unclean theories. Regardless of the society you live in, the historian’s pen has shown that nearly every society has its origins in bigotry, discrimination, conquest, servitude, and exploitation. Governments and rulers have spent much of their time spinning theories of superiority to justify their grip on power. To make it respectable and give it the illusion of morality, they package privilege and power as political ideology. 12 We do the same thing at a personal level as we marinate in notions of supremacy and award ourselves elevated status.

Key concept: We like to tell ourselves soothing stories to justify our sense of superiority.

Theories of superiority are attempts to show how, in the words of George Orwell, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” I remember reading Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a student. I had to hold my nose but I kept reading because I was fascinated that this clever work of eugenics-based grandiosity had influenced so many people. It’s beguiling when someone tells you that you’re better than everyone else, that you’ve been unjustly dealt with, and that you deserve more.

It’s the same facile thesis we find in all theories of superiority and biological determinism, and all attempts at intellectual imperialism. It begins with a false claim of superiority, or election, on some grounds, and then moves to a call to action: you’re in the minority, you’re in danger, and you need to rise up and defend yourself. Unfortunately, absurd strains of social Darwinism have always been effective when presented with urgency and erudition. People fall for it. And it really doesn’t matter whose theory of superiority you read; they’re all meditations in hypocrisy, bathed in jingoism, resting on the same veiled attempts to preserve the vassalage of the past.

Key question: Do you feel superior to other people? If so, why?

Shocking as it may sound, theories of superiority have dominated human societies for millennia. As one of the first power theorists, Aristotle declared, “It is clear that some men are by nature free and others by nature slaves, and that for these latter, slavery is both expedient and right.” 13 We have libraries filled with theories of superiority because we have an irrepressible desire to be just a little more special than the next person. John Adams wrote, “I believe there is no one principle which predominates in human nature so much in every stage of life, from the cradle to the grave, in males and females, old and young, black and white, rich and poor, high and low, as this passion for superiority.” 14

With history to ponder, how can we excuse ourselves on the premise that human nature is full of paradoxes, contradictions, and complexities. It’s dangerous and incorrect to dismiss the natural-rights tradition as just one of many propaganda traditions. How many times have we dressed up vanity as moral philosophy? How many times have we disguised elitism as the naturally stratified order of heaven?

Thankfully, many people don’t subscribe to these pretensions. But many do. In our modern society, we have long since repudiated the grand theories of bloodline aristocracy, but we continue to hatch, nurse, and perpetuate informal versions that do the same thing. They show up as stereotype, resentment, bias, and prejudice and linger in our values, assumptions, and behavior.

When I began my service as plant manager at Geneva Steel, I conducted a series of tours throughout the plant. I traveled from facility to facility, holding town hall meetings, greeting the managers and production and maintenance workers. I started at the coke plant, and then moved to the blast furnaces, steel-making operations, casting, rolling mills, finishing units, shipping and transportation, and central maintenance.

In the coke plant, two production workers cornered me. They removed their hard hats and safety goggles, revealing faces caked with sweat and soot. “Mr. Clark,” they said deferentially, “thank you for coming to visit our department. We know you’re new to your position as plant manager. We know you’re going to visit all the departments, but we just wanted you to know that our department is a little different than the others. Our department is a little more complicated than the others, and it requires a little more expertise to do what we do. If we weren’t here, the plant would shut down tomorrow.” They made their case and stated their claim. I politely responded, “Thank you for sharing that with me. I appreciate your feedback.”

That scene repeated itself in every department. The faces were different, but the script was the same. After my weeklong tour, I was illuminated with the revelation that every department was just a little more important than the others, occupied by a special class of people, doing what no one else could do. They all gently shunted their brothers and sisters in order to distinguish themselves. I suppose we have all made, or been tempted to make, a similar claim and fallen prey to the grand illusion of superiority.

Key questions: Is the moral principle of inclusion a convenient or inconvenient truth for you?

The Elite and the Great Unwashed

The US Constitution lights the world with an unequivocal declaration of human rights, but it’s taken generations to find the courage to unwind legalized discrimination and dismantle the edifice of false superiority. In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote her husband, John, “I desire that you would Remember the Ladies. We will not have ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.” Two years later, the original American colonies ratified the US Constitution. Although the document was the first government charter that acknowledged the equality of all human beings, it carved out exceptions and violated the ideals it espoused, allowing slavery, counting slaves as equal to a three-fifths of a “normal” human, and not least, withholding voting rights from women. Nor could women own property, keep their own wages, or, in some states, even choose their own husbands. The US Constitution decreed inclusion, but too often we practiced exclusion. It would still take many generations to internalize the espoused values because theories of superiority were deeply ingrained in the American psyche as they were in every nation. 15 Consider the following official acts of exclusion:

• Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1790, declaring that only white people could become citizens of the nation.

• Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 to drive out Native Americans from their tribal lands.

• Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, but states passed Jim Crow laws to enforce discrimination, and the Supreme Court piled on with its “separate but equal” legal doctrine.

• In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese immigration.

• In 1910, 1.6 million children aged ten to fifteen worked in factories. The Fair Labor Standards Act didn’t ban child labor until 1938.

• Women did not win the right to vote until we passed the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

• In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the evacuation and incarceration of 127,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast to internment camps.

• Hispanic American workers didn’t gain the right to unionize until the 1950s.

• Ultimately, we didn’t purge deliberate and systematic prejudice out of our immigration laws until the Immigration Act of 1965.

But what about our culture? We continue to struggle to redress inequality and forsake notions of male and Anglo-Saxon supremacy. As my teenage daughter asks, “Dad, why is gender wage equity still a thing?”

We have purged most of our policies of discrimination, but have our hearts changed? Have we become a more inclusive society? A recent EY study reports that less than half of employees trust their bosses and employers. 16 Where there’s no trust, there’s exclusion. This number is troubling because we know that trust is what binds us together. 17 If familiarity based on frequency of interaction has this amazing ability to eliminate bias and distrust, why are trust numbers so low?

This is the “society versus community” dichotomy. 18 We would expect to see a trusting community within a more distrustful society. There should be proportionately more trust as we move to smaller social units. Organizations should have more trust than governments. Teams should have more than organizations. Families should have more than teams, and marriages should have the most. There should be more good faith and lower transaction costs in our interactions as we move from big to small. 19 If this is true, and I think it is, we get nowhere until we grant each other inclusion safety.

Who’s getting in the way? The psychologist Carol Dweck has said, “Your failures and misfortunes don’t threaten other people. It’s your assets and your successes that are problems for people who derive their self-esteem from being superior.” 20 The irony is that because of our insecurity we refuse to validate each other, which is the very thing that heals the insecurity. That unmet need expresses itself in jealousy, resentment, and contempt. Meanwhile, society is filled to overflowing with incivility, and hate has become a growth industry.

Key concept: Excluding a person is more often the result of personal unmet needs and insecurities than a genuine dislike of the person.

How many times have you been suspicious or critical of someone you didn’t really know, and when you got to know that person, your entire attitude changed? Differences tend to repel us initially, but when we suspend judgment, we can bridge those differences. When I was in college, I took a class from a professor with radical views and braced myself for combat. I went to class and learned that this gentleman did indeed hold views very different from my own, but we developed a wonderful Ruth Bader Ginsberg–Antonin Scalia–like friendship. We had marvelous disagreements but maintained a deep respect for each other. If we don’t watch ourselves, there are a thousand ways to withhold inclusion safety. And if we dehumanize each other, we give ourselves permission to hate and harm each other.

I once worked with an executive team whose members had withdrawn inclusion safety from each other. They were legal officers of a corporation but had revoked each other’s cultural passports. The team was dysfunctional. They would verbally bruise and bludgeon each other and could barely stand to be in the same room. In my interview with one of them, she said, “We don’t have to like each other; we just have to work together, so I guess it doesn’t really matter. I’m all about getting the job done. I don’t care too much about the relationships anyway.”

I worked with another leader who asserted dominance through an arbitrary pattern of giving and revoking inclusion safety. You were in his good graces one day, out the next, respected then neglected, heard then ignored, fawned over then forgotten, coached then coerced, healed then hurt. Let’s be clear: head games are a form of abuse in which one human toys with another. That pattern of interaction is moral cowardice at its finest.

Family as the Realm of Thick Trust

The word accept means to consent to receive. The word inclusion means having the status of association or connection to a group. Now think about these two words as it relates to the family unit. The relationship between husband and wife is based on the consent to receive the other. The family unit that is created from that union is a new entity to which both are parties. If one spouse denies membership to the other, the social unit doesn’t function. The legal tie that binds them together may be intact, but the reality of their union has evaporated.

The interdependence of the marriage relationship is more fundamental than in any other social collective. It is fragile and yet designed to be the realm of the thickest trust. At any moment, one party may withdraw inclusion safety from the other. The respect and permission to participate that each gives the other is the very basis of their interdependency, their success, and their happiness. That inclusion safety is dynamic and perishable. It must be replenished every day. Particularly in marriage, respect must be translated into acts of kindness, service, and sacrifice. Without a consistent investment in gestures of respect, the relationship will wither from neglect. But in a coequal partnership, in which both spouses participate and permit the other equal power and participation rights, the relationship is likely to produce sustainable, high levels of inclusion safety and a deeply fulfilling experience for both.

The relationship between parents and children is somewhat different. Children begin life in a stage of dependence and hopefully move to a stage of interdependence as they learn and grow. A stage of pure independence is of course a fiction. In the development process, the intersection of love and accountability is all important. Parents shouldn’t condone poor behavior, but neither should they condemn the child for it. The child is much more able to learn both rights and responsibility in a nurturing environment of sustained inclusion safety. It’s over the elusive combination of love and accountability that so many of us stumble. I’ve stumbled many times, but often to my children’s dismay, I’ve learned to say, “I love you and I’m going to hold you accountable” in the same sentence and mean it.

Key questions: The basic social unit of the family is the primary laboratory for gaining a true civic education in inclusion safety. Did you learn it in your family? If not, do you intend to be a transformational figure in your family and model inclusion safety for the next generation?

Behave until You Believe

What if you can’t find the conviction to include someone? What if you have a deep-seated bias or prejudice that you can’t dislodge from your heart? How do you overcome it? Where do we find, to use Kafka’s phrase, “the ax for the frozen sea within us”? 21 One thing that doesn’t work very well is to sit back and wait for your heart to change.

There’s not a person alive without at least some trace elements of negative bias against some human characteristic. But some of us are more blameworthy than others. We need to be honest about the acquisition of bias and prejudice and work hard to remove it. We don’t get to make choices about diversity; diversity simply is. It’s our job to embrace it.

Key questions: What conscious bias do you have? Ask a trusted friend where you may have unconscious bias. Finally, where do you exercise soft forms of exclusion to maintain barriers?

Learn to love yourself first. People with low self-regard have a hard time being inclusive. Whatever your level of self-regard, it spills into your interpersonal behavior. As Nathaniel Branden observes, “Research shows that a well-developed sense of personal value and autonomy correlates significantly with kindness, generosity, social cooperation, and a spirit of mutual aid.” 22 The best and quickest way to develop self-regard is to develop your own capacity and confidence and to perform acts of service for others, especially for those whom you struggle to include.

Think about the traditional approaches most organizations take to diversity and inclusion. Many organizations have made great strides to create diverse organizations, but they’re still not inclusive. Others achieve a token representation of the full range of human differences and congratulate themselves as if they have an inclusive culture. Still others train employees to be inclusive by teaching them awareness, understanding, and appreciation for differences. That’s nice, but it’s a coat of paint. 23 When we feel threatened, we get defensive, take counsel from our fears, and go back to our default settings of learned bias. A better way is to give people opportunities to practice inclusion. Make it experiential by creating diverse teams and assigning individuals to diverse mentoring or peer coaching relationships.

Key concept: You learn inclusion when you practice inclusion. Behave until you believe.

Inclusive behavior produces its own confirming evidence. 24 The call to action is simple: affirm the individual worth of other human beings. Do I mean fake it until you feel it? Lease your kindness? Pretend? Wear the mask of an inclusive person? No, I mean earnest striving with real intent.

Key concept: As you love people with action, you come to love them with emotion.

The feeling of love is the reward of the action of love. In fact, if we fail to serve others, our relationships remain superficial, and even suspicious, until we close the distance. In that closeness, in living, working, eating, and breathing together, regard and affection finally arrive. If you don’t feel the way you want to feel, or know you should feel, toward an individual or group, the passage of time won’t change that, but your actions will. Act yourself into the emotion of love.

I’ve lived and worked with people from all parts of the world. I love them all and yet I realize that every nation, society, and family thinks it’s special. If we take special to mean singular or unique, I wholeheartedly agree. But if we take it to mean that we are better than our neighbors, I know where that comes from. We all want to count. We all want to matter. Unfortunately, we often convince ourselves that subordinating others will allow us to count and matter more. The sense of superiority we feel when we put others down is pure self-deception.

Key concept: No person living in a prison of prejudice can be truly happy or free. 25

Key questions: What individual or group are you having a hard time including even if they are doing you no real harm? Why?

Key Concepts

• The choice to include another human being activates our humanity.

• We include naturally in childhood and exclude unnaturally in adulthood.

• Including another human being should be an act of prejudgment based on that person’s worth, not an act of judgment based on that person’s worthiness.

• Instead of granting inclusion safety based on human status, we tend to judge another person’s worthiness based on indicators like appearance, social status, or material possessions, when those indicators have nothing to do with worthiness.

• God may have made us of different clay, but there are no grounds to say that your clay is better than mine.

• In any social unit, inclusion safety can be granted, withheld, revoked, or partially or conditionally granted.

• We like to tell ourselves soothing stories to justify our sense of superiority.

• Excluding a person is more often the result of personal unmet needs and insecurities than a genuine dislike of the person.

• You learn inclusion when you practice inclusion. Behave until you believe.

• As you love people with action, you come to love them with emotion.

• No person living in a prison of prejudice can be truly happy or free.

Key Questions

• Do you treat people that you consider of lower status differently than those of higher status? If so, why?

• In the arc of every life are times when inclusion safety makes all the difference, when someone reaches out to include you at a vulnerable time. When did this happen to you? What impact did it have on your life? Are you paying it forward?

• How do you acknowledge and show sensitivity and appreciation for the cultural differences that exist on your team?

• Do you feel superior to other people? If so, why?

• Is the moral principle of inclusion a convenient or inconvenient truth for you?

• The basic social unit of the family is the primary laboratory for gaining a true civic education in inclusion safety. Did you learn it in your family? If not, do you intend to be a transformational figure in your family and model inclusion safety for the next generation?

• What conscious bias do you have? Ask a trusted friend where you may have unconscious bias. Finally, where do you exercise soft forms of exclusion to maintain barriers?

• What individual or group are you having a hard time including even if they are doing you no real harm? Why?