Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

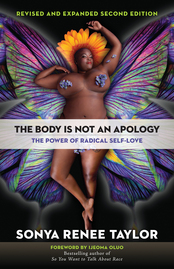

The Body is Not an Apology 2nd Edition

The Power of Radical Self-Love

Sonya Renee Taylor (Author)

Publication date: 02/09/2021

—Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and founder and Executive Director, African American Policy Forum

Humans are a varied and divergent bunch with all manner of beliefs, morals, and bodies. Systems of oppression thrive off our inability to make peace with difference and injure the relationship we have with our own bodies.

The Body Is Not an Apology offers radical self-love as the balm to heal the wounds inflicted by these violent systems. World-renowned activist and poet Sonya Renee Taylor invites us to reconnect with the radical origins of our minds and bodies and celebrate our collective, enduring strength. As we awaken to our own indoctrinated body shame, we feel inspired to awaken others and to interrupt the systems that perpetuate body shame and oppression against all bodies. When we act from this truth on a global scale, we usher in the transformative opportunity of radical self-love, which is the opportunity for a more just, equitable, and compassionate world—for us all.

This second edition includes stories from Taylor's travels around the world combating body terrorism and shines a light on the path toward liberation guided by love. In a brand new final chapter, she offers specific tools, actions, and resources for confronting racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia. And she provides a case study showing how radical self-love not only dismantles shame and self-loathing in us but has the power to dismantle entire systems of injustice. Together with the accompanying workbook, Your Body Is Not an Apology, Taylor brings the practice of radical self-love to life.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

—Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and founder and Executive Director, African American Policy Forum

Humans are a varied and divergent bunch with all manner of beliefs, morals, and bodies. Systems of oppression thrive off our inability to make peace with difference and injure the relationship we have with our own bodies.

The Body Is Not an Apology offers radical self-love as the balm to heal the wounds inflicted by these violent systems. World-renowned activist and poet Sonya Renee Taylor invites us to reconnect with the radical origins of our minds and bodies and celebrate our collective, enduring strength. As we awaken to our own indoctrinated body shame, we feel inspired to awaken others and to interrupt the systems that perpetuate body shame and oppression against all bodies. When we act from this truth on a global scale, we usher in the transformative opportunity of radical self-love, which is the opportunity for a more just, equitable, and compassionate world—for us all.

This second edition includes stories from Taylor's travels around the world combating body terrorism and shines a light on the path toward liberation guided by love. In a brand new final chapter, she offers specific tools, actions, and resources for confronting racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia. And she provides a case study showing how radical self-love not only dismantles shame and self-loathing in us but has the power to dismantle entire systems of injustice. Together with the accompanying workbook, Your Body Is Not an Apology, Taylor brings the practice of radical self-love to life.

1

Making Self-Love Radical

What Radical Self-Love Is and What It Ain’t

Let me answer a couple of questions right away before you dig too deeply into this book and are left feeling bamboozled and hoodwinked. First, “Will this book fix my self-esteem, Sonya?” Nope. Second, “Will this book teach me how to have self-confidence?” Nah. Impromptu third question, “Well, then, why in Hades am I reading this book?” You are reading this book because your heart is calling you toward something exponentially more magnanimous and more succulent than self-esteem or self-confidence. You are being called toward radical self-love. While not completely unrelated to self-esteem or self-confidence, radical self-love is its own entity, a lush and verdant island offering safe harbor for self-esteem and self-confidence. Unfortunately, those two ships often choose to wander aimlessly adrift at sea, relying on willpower or ego to drive them, and in the absence of those motors are left hopelessly pursuing the fraught mirage of someday. As in, “Someday I will feel good enough about myself to shop that screenplay I wrote.” Or, “Someday, when I have self-confidence, I will get out of this raggedy relationship.” Self-esteem and self-confidence are fleeting, and both can exist without radical self-love, but it almost never bodes well for anyone involved when they do. Think of all the obnoxious people you know oozing arrogance, folks we can be certain think extremely highly of themselves. Although you may call them . . . ahem . . . confident (at least that may be one of the things you call them), I bet the phrase radical self-love doesn’t quite fit. Pick your favorite totalitarian dictator and you will likely find someone who has done just fine in the self-confidence category. After all, you would have to think you’re the bee’s knees to entertain the idea of single-handedly dominating the entire planet. The forty-fifth U.S. president strikes me as a man with epic self-confidence. “The Donald” is not struggling with his sense of self (even if the rest of the world is struggling with its sense of who he is). Even if we were to surmise that Trump and others like him are acting from an exaggerated lack of self-esteem or confidence, I think we can agree not many of their attitudes or actions feel like love.

The biggest flaw of investing our time in self-esteem and self-confidence is that neither model unto itself has the ability to reorient our world toward justice and compassion. Self-esteem and self-confidence aren’t scalable. The term scalable is most frequently heard in the economic or business start-up world and is used to describe “a company’s ability to grow without being hampered by its structure or available resources when faced with increased production.”1 If self-esteem and confidence are primarily fueled by ego and external conditions, they are inevitably going to be a shaky platform upon which to build full, abundant lives. If they can barely hold up our expanding dreams and awakenings, they are certain to buckle under the weight of oppression. On the contrary, radical self-love builds a foundation strong enough to carry the enormous power of our highest calling while also connecting us to the potential power of all bodies. If radical self-love is an oak tree, it is an essential part of an entire ecosystem. When it grows stronger, the entire system does as well. Radical self-love starts with the individual, expands to the family, community, and organization, and ultimately transforms society. All while still unwaveringly holding you in the center of that expansion. That, my friend, is scale.

You may be asking, “Okay, well, if this book won’t help me with my self-esteem or self-confidence, will it at least teach me self-acceptance?” My short answer is, if I do my job correctly, no! Not because self-acceptance isn’t useful, but because I believe there is a port far beyond the isle of self-acceptance and I want us to go there. Think back to all the times you “accepted” something and found it completely uninspiring. When I was a kid, my mother would make my brother and me frozen pot pies for dinner. It was the meal for the days she did not feel like cooking. I enjoyed the flaky pastry crust. The chunks of mechanically pressed chicken in a Band-Aid-colored beige gravy were tolerable. But there was nothing less appetizing than the abhorrent vegetable medley of peas, green beans, and carrots portioned throughout each bite like miserable stars in an endless galaxy. Yes, I ate those hateful mixed vegetables. Hunger will make you accept things. I accepted that my options were limited: pick out a million tiny peas or get a job at the ripe age of ten and figure out how to feed myself. Why am I talking about pot pies? Because self-acceptance is the mixed-veggie pot pie of radical self-love. It will keep you alive when the options are sparse, but what if there is a life beyond frozen pot pies?

Too often, self-acceptance is used as a synonym for acquiescence. We accept the things we cannot change. We accept death because we have no say over its arbitrary and indifferent arrival at our door. We have personal histories of bland acceptance. We have accepted lackluster jobs because we were broke. We have accepted lousy partners because their lousy presence was better than the hollow aloneness of their absence. We practice self-acceptance when we have grown tired of self-hatred but can’t conceive of anything beyond a paltry tolerance of ourselves. What a thin coat to wear on this weather-tossed road. Famed activist and professor Angela Davis said, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.”2 We can change the circumstances that have had us settle for self-acceptance. I assure you there is a richer, thicker, cozier blanket to carry through the world. There is a realm infinitely more mind-blowing. It’s called radical self-love.

Radical Reflection

Concepts like self-acceptance and body neutrality are not without value. When you have spent your entire life at war with your body, these models offer a truce. But you can have more than a cease-fire. You can have radical self-love because you are already radical self-love.

Why the Body?

Humans are a varied and divergent bunch, with all manner of beliefs, morals, values, and ideas. We have struggled to find agreement on much of anything over the centuries (just think about how long we argued about gravity and whether the world is shaped like a pizza), but here is a completely noncontroversial statement I think we have consensus around: You, my dear, have a body. And should you desire to remain on this spinning rock hurtling through space, you will need a body to do it. Everything else we think we know is up for debate. Are we spiritual beings? Depends on whom you ask. Do humans have souls? Been fighting about that since Aristotle likened the souls of fetuses to those of vegetables.3 But bodies—yup, we got those. And given this widely agreed-upon reality, it seems to me if ever there were a place where the practice of radical love could be a transformative force, the body ought to be that location.

When we speak of the ills of the world—violence, poverty, injustice—we are not speaking conceptually; we are talking about things that happen to bodies. When we say millions around the world are impacted by the global epidemic of famine, what we are saying is that millions of humans are experiencing the physical deterioration of muscle and other tissue due to lack of nutrients in their bodies. Injustice is an opaque word until we are willing to discuss its material reality as, for example, the three years sixteen-year-old Kalief Browder spent beaten and locked in solitary confinement in Riker’s Island prison without ever being charged with a single crime. His suicide and his mother’s heart attack two years later are not abstractions; they are the outcomes injustice enacted on two bodies.4 Racism, sexism, ableism, homo- and transphobia, ageism, fatphobia are algorithms created by humans’ struggle to make peace with the body. A radical self-love world is a world free from the systems of oppression that make it difficult and sometimes deadly to live in our bodies.

A radical self-love world is a world that works for every body. Creating such a world is an inside-out job. How we value and honor our own bodies impacts how we value and honor the bodies of others. Our own radical self-love reconnection is the blueprint for what author Charles Eisenstein calls The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible.5 It is through our own transformed relationship with our bodies that we become champions for other bodies on our planet. As we awaken to our indoctrinated body shame, we feel inspired to awaken others and to interrupt the systems that perpetuate body shame and oppression against all bodies. There is a whisper we keep hearing; it is saying we must build in us what we want to see built in the world. When we act from this truth on a global scale, using the lens of the body, we usher in the transformative opportunity of radical self-love, which is the opportunity for a more just, equitable, and compassionate world for us all.

Moving from body shame to radical self-love is a road of inquiry and insight. We will need to ask ourselves tough questions from a place of grace and grounding. Together we will examine what we have come to believe about ourselves, our bodies, and the world we live in. At times, the road may appear dark and ominous, but fret not, my friend! I have provided some lampposts along the way. They come in the form of Unapologetic Inquiries, questions you will ask yourself as you endeavor to explore the mechanisms of your body shame and dismantle its parts. Radical Reflections will highlight central themes and concepts you will want to remember as we take this journey together. This is not a math test and you cannot fail. Be patient with yourself, take your time. As my best friend Maureen Benson says, “You are not late.”6

Why Must It Be Radical?

“Okay, Sonya. I get it. Loving ourselves is important. But why do we have to be all radical about it?” To answer this question is to further distinguish radical self-love from its fickle cousins, self-confidence and self-esteem, or its scrappy kid sister, self-acceptance. It requires that we explore the definition of the word radical. Language is fluid and evolutionary, regularly leaving dictionary definitions feeling dated and sorely lacking in nuance. How we construct language is an enormous part of how we understand and judge bodies. The definition of radical is a powerful one as we explore its relationship to self-love. Dictionary.com defines radical as:

- of or going to the root or origin; fundamental: a radical difference.

- thoroughgoing or extreme, especially as regards change from accepted or traditional forms: a radical change in the policy of a company.

- favoring drastic political, economic, or social reforms: radical ideas; radical and anarchistic ideologues.

- forming a basis or foundation.

- existing inherently in a thing or person: radical defects of character.7

Radical self-love is deeper, wider, and more expansive than anything we would call self-confidence or self-esteem. It is juicier than self-acceptance. Including the word radical offers us a self-love that is the root or origin of our relationship to ourselves. We did not start life in a negative partnership with our bodies. I have never seen a toddler lament the size of their thighs, the squishiness of their belly. Children do not arrive here ashamed of their race, gender, age, or differing abilities. Babies love their bodies! Each discovery they encounter is freaking awesome. Have you ever seen an infant realize they have feet? Talk about wonder! That is what an unobstructed relationship with our bodies looks like. You were an infant once, which means there was a time when you thought your body was freaking awesome too. Connecting to that memory may feel as distant as the farthest star. It may not be a memory you can access at all, but just knowing that there was a point in your history when you once loved your body can be a reminder that body shame is a fantastically crappy inheritance. We didn’t give it to ourselves, and we are not obligated to keep it. We arrived on this planet as LOVE.

We need not do anything other than turn on a television for evidence affirming how desperately our society, our world, needs an extreme form of self-love to counter the constant barrage of shame, discrimination, and body-based oppression enacted against us daily. Television shows like The Biggest Loser encourage dangerous and unsustainable exercise and food restriction from their contestants while using their bodies as fodder for our entertainment and reinforcing the notion that the most undesirable body one can have is a fat body. Researchers have shown that American news outlets regularly exaggerate crime rates, including a tendency to inflate the rates of Black offenses while depicting Black suspects in a less favorable light than their White counterparts.8 People with disabilities are virtually nonexistent on television unless they are being trotted out as “inspiration porn.” Their stories are often told in ways that exploit their disabilities for the emotional edification of able-bodied people, presenting them as superhuman for doing unspectacular things like reading or going to the store or, worse yet, for overcoming obstacles placed on them by the very society that fails to acknowledge or appropriately accommodate their bodies.9 Of course we need something radical to challenge these messages.

Using the term radical elevates the reality that our society requires a drastic political, economic, and social reformation in the ways in which we deal with bodies and body difference. The U.S. Constitution was written to sanction governmental body oppression. When the Bill of Rights was signed, relatively few Americans had voting rights.10 Among those excluded from suffrage were African Americans, Native Americans, women, White men with disabilities, and White males who did not own land. Voting rights for women . . . nope. Blacks . . . nope; they were only counted as three-fifths of a full person. Using a wheelchair? No voting for you, dear. Race, gender, and disability prejudice were written into the governing documents of the United States.11 Consider that the right to marry the person you love regardless of your gender was only legally sanctioned in the United States in 2015.12 Out of 195 countries in the world, same-sex marriage is legal in only 30 of them.13 Marriage equality for same-sex couples is in its historical infancy in the United States and nonexistent for most of the world. Transgender people are currently fighting across the United States to retain the legal right to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity.14 People with disabilities have higher rates of unemployment regardless of educational attainment.15

These political, economic, and social issues are about our bodies. They intersect with our race, age, gender, ability, sexual orientation, and a multitude of other ways our bodies exist. In 1989, Columbia law professor and scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw gave a name to this long-understood dynamic. She called it intersectionality and defined it as:

the study of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination. The theory suggests that—and seeks to examine how—various biological, social, and cultural categories such as gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, religion, caste, age, and other axes of identity interact on multiple and often simultaneous levels. The theory proposes that we should think of each element or trait of a person as inextricably linked with all of the other elements in order to fully understand one’s identity.16

Intersectionality has become a term often revered or repudiated depending on the source. Put plainly, none of us is mono-dimensional. We are not only men, fathers, people living with lupus, Asian, or seniors. Some of us are aging Asian fathers who are living with lupus. Those varying identities impact each other in ways that are significantly different than if we were navigating them one at a time. Radical self-love demands that we see ourselves and others in the fullness of our complexities and intersections and that we work to create space for those intersections. As has been true throughout history, changing the systemic and structural oppressions that regard us in perfunctory and myopic ways requires sweeping changes in our laws, policies, and social norms. Creating a world of justice for all bodies demands that we be radical and intersectional.

Unapologetic Inquiry #1

We all live at multiple intersections of identity. What are your intersections? How do your multiple identities affect each other?

Radical self-love is interdependent. The radical self-love espoused in this book lives beyond the flimsy ethos of individualism and operates at both the individual and systemic levels. Radical self-love is about the self because the self is part of the whole. And therefore, radical self-love is the foundation of radical human love. Our relationships with our own bodies inform our relationships with others. Consider all the times you have assessed your value or lack thereof by comparing yourself to someone else. When we are saddled with body shame, we see other bodies as things to covet or judge. Body shame makes us view bodies in narrow terms like “good” or “bad,” or “better” or “worse” than our own. Radical self-love invites us to love our bodies in a way that transforms how we understand and accept the bodies of others. This is not to say that we magically like everyone. It simply means we have debates and disagreements about ideas and character, not about bodies. When we can see the obvious truth inherent in artist and activist Glen Marla’s quote, “There is no wrong way to have a body,” we learn to love bodies even when we don’t like the humans inhabiting them.17

Our personal radical self-love transformation alters the workings of the world. Model Cacsmy Brutus exemplified this principle in life. Mama Cax, as she was known, was a Haitian-born Black woman diagnosed with osteosarcoma and lung cancer when she was fourteen years old. A failed hip replacement after her cancer treatment forced her to have her leg amputated, and for years after her amputation, she tried to hide her prosthetic leg, her body shame spiraling into years-long depression. On March 14, 2013, she posted a simple photo on Instagram standing in a short yellow dress with her prosthetic leg unapologetically visible. The caption stated, “I read somewhere that freedom lies in being yourself. I hope you guys are free.” Cacsmy feared the world would meet the sight of her prosthetic leg with pity, but instead her community heralded her as a “badass.” That small radical step illuminated a path toward her purpose that would have remained obscured, camouflaged behind years of shame, if not for a series of small but life-altering acts. I came to know of Mama Cax in 2017 after she began her professional modeling career. She went from working in the New York mayor’s office to being represented by a major New York modeling agency and walking in runway shows for Chromat and Rihanna’s Fenty lingerie. She was bald and dark just like me, disabled and unapologetically so. She was a necessary brick in building a monument of radical self-love for the planet, and her choice to embrace her body, disabilities, and difference brought her out of the shadows and in front of hundreds of thousands of people who needed to know a Mama Cax was possible in the world. She not only transformed her life, she also contributed to a transformation in the visibility and accessibility of disabled bodies, Black bodies, immigrant bodies in careers previously blocked from them. Mama Cax in her radical majestic body played a key part in the diversity we currently see in the beauty and fashion industry. Be clear: these industries are nowhere near equitable and still primarily uphold impossible standards of beauty, but narratives about which bodies deserve to be seen and celebrated have begun shifting. We can feel the ground shaking beneath those impossible standards and in no small part because of what Mama Cax did to advance a new vision of beauty and power. Mama Cax died on December 16, 2019. She was just thirty years old. Her brief but mighty life is a reminder that our personal radical self-love journey is a stream inseparable from the ocean of change radical self-love makes possible.18

Unapologetic Inquiry #2

Can you recall an occasion when you compared yourself to someone? How did the comparison impact your self-esteem and self-confidence? How did it impact your ideas about the other person?

Radical self-love is indeed our inherent natural state, but social, political, and economic systems of oppression have distanced us from that knowing. Remember that toddler I mentioned a few paragraphs ago who delighted in their wondrous body—a.k.a. you as a kid? I know radical self-love can seem like a planet outside any galaxy you’ve heard of. I want to assure you: radical self-love is not light years away. It is not away at all. It lives in you. It is your very essence. You do not have to become radical self-love. You don’t have to try to travel to it as though it were some far-off destination. Think of body shame like the layers of an onion. For decades in our own lives and for centuries in civilization, we have been taught to judge and shame our bodies and to consequently judge and shame others. Getting to our inherent state of radical self-love means peeling away those ancient, toxic messages about bodies. It is like returning the world’s ugliest shame sweater back to the store where it was purchased and coming out wearing nothing but a birthday suit of radical self-love. By refusing to accept body shame as some natural consequence of being in a body, we can stop apologizing for our bodies and erase the distance between ourselves and radical self-love. When we do that, we are instantly returned to the radically self-loving stars we always were. Talk about a transformative power!

What Have We Been Apologizing For? What If We Stopped?

As a nine-year-old, I was sorry for everything. “Sonie, you left the refrigerator open!” “Sorry.” “Sonya, why is your coat on the couch?” “Sorry.” “Sonya, did you get grape jelly on that white pantsuit I paid good money for?” “Sorry, sorry, sorry . . .” A litany of apologies for my ever clumsy, messy, forgetful self, who spilled evidence of such all over the house. “Sorry” was my way of gathering up the spill. After all, I was a new generation of “raising kids” my grandmother was enlisted to do after having already raised three children on her own. I knew that my grandmother loved me, but even at nine years old I also knew she had to be exhausted. Grandma eventually started scolding me for saying sorry all the time. “Hush all that sorry. You ain’t sorry. If you were sorry you would stop doing it!” I wondered if there was any truth to my grandmother’s admonishment. If I were sorry, truly sorry, would I stop doing whatever it was? Could I?

Living in a female body, a Black body, an aging body, a fat body, a body with mental illness is to awaken daily to a planet that expects a certain set of apologies to already live on our tongues. There is a level of “not enough” or “too much” sewn into these strands of difference. Recent discoveries in the field of epigenetics have established how the traumas and resiliency of our ancestors are passed on to us molecularly.19 Being sorry is literally a lesson in our DNA. In the Jim Crow South, an apology could at times be exacted by death sentence. Emmett Till’s family came to know this brutal fact in the summer of 1955, when the fifteen-year-old’s obligatory apology for whistling at a White woman would come in the form of a fatal gunshot after which his lifeless body was affixed to a tire and dumped in the Tallahatchie River.20 For far too many women, the expectation of apology began after the sexual-assault report ended in an interrogation about the length of the skirt she was wearing or how many drinks she had at the party. There are minuscule daily ways each of us will be asked to apologize for our bodies, no matter how “normal” they appear. The conservative haircut needed to placate the new supervisor, the tattoo you cover when you step into an office building to increase your chances of being treated “professionally” are examples of tiny apologies society will ask you to render for being in your body as you see fit. For so many of us, sorry has become how we translate the word body.

Unapologetic Inquiry #3

In what ways have you been asked to apologize for your body?

For decades, I spread out before the world a buffet of apologies. I apologized for laughing too loudly, being too big, too dark, flamboyant, outspoken, analytical. I watched countless others roll out similar scrolls of contrition. We made these apologies because our bodies had disabilities and needed access. We made them because our bodies were aging and slower, because our gender identity was different than the sex we were assigned at birth and it confused strangers. We apologized for our weight, race, sexual orientation. We were told there is a right way to have a body, and our apologies reflected our indoctrination into that belief. We believed there was indeed a way in which our bodies were wrong. Not only have we been trying to change our “wrong bodies,” but we have also continued to apologize for the presumed discomfort our bodies rouse in others. Whether we perceived ourselves as making the passenger beside us uncomfortable by taking up “too much” space in our airplane seat or we believed that our brown skin frightened the White woman who clutched her purse and crossed the street when she saw us approaching, either way it was in these moments that we found our heads bowed in shame, certain that our too fat, too dark, too muchness was the offense. It is never the failure of the seat or of its makers, who opted not to design it for myriad bodies. Of course, it is not our media companies’ exaggeration of crime in communities of color that is culpable for planting the seeds of prejudice in so many citizens. We, at every turn, have decided that we are the culprits of our own victimization. However, not only are we constantly atoning; we have demanded our fair share of apologies from others as well. We, too, have snickered at the fat body at the beach, shamed the transgender body at the grocery store, pitied the disabled body while clothes shopping, maligned the aging body. We have demanded the apology from other bodies. We have ranked our bodies against the bodies of others, deciding they are greater or lesser than our own based on the prejudices and biases we inherited.

Dismantling the culture of apology requires an investigation into the anatomy of an apology. Generally, people committed to their righteousness rarely feel the need to apologize. About five years ago I shared with an ex how something he’d said had hurt my feelings. After twenty minutes of his dancing around any admission of offense, it became clear this guy was not planning to issue any apologies. According to his logic, he did not intend to hurt my feelings and therefore did not owe me an apology. Like many people, he felt that his intention should have absolved him from his impact. I countered his reasoning by asking, “If you accidently stepped on someone’s foot, would you say sorry?” “No, not if their foot was the only place to stand,” he replied matter-of-factly. (Why had I dated this guy?) Clearly, I do not propose that we, as a species, adopt this sort of thoughtless, self-centered ideology, but sometimes even jerks can lead us to epiphanies. There was something about his refusal to apologize for what he saw as taking up the space he needed that, if wielded authentically, might change how we move through the world.

In a conversation on a podcast called Myelin and Melanin, which highlights the unique challenges of being Black and living with multiple sclerosis, the host shared how for years she avoided using mobility aids such as canes or a wheelchair. She felt uncomfortable not only with the visibility of her disability but how such aids took up what she called “too much space.” Take a moment to consider that space is actually infinite, right? The notion of “taking too much space” is born out of a framework of scarcity upon which we have built a world where some people are allowed to build skyscrapers and stadiums or run countries and make laws for the masses, while others are told to stay small, go unnoticed, don’t take up too much room on the sidewalk. But only some of us receive that message. We have yet to collectively tell Amazon gazillionaire Jeff Bezos or Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, “Hey, buddy, you’re just taking up too much space!”

Space is infinite and yet it is possible to be out of balance. With canyon-sized wealth gaps feeding global poverty but not bellies, billionaires are out of balance. Those of us who believe we do not have the “right body” spend decades of our life and dollars trying to shrink, tuck, and tame ourselves into the right body all the while forfeiting precious space on the planet because we don’t feel entitled to it. We, too, are out of balance. Some of us have no problems taking up space (google manspreading), while others move closer to invisibility daily. I long for a mutiny of space. May there be ten million wheelchairs, canes, service dogs, and mobility aids on every street in every country. Let there be double seats for every fat body, and may every boardroom and decision-making entity be brimming with young and old, Black, Brown, and transgender bodies. Taking up space we have previously been denied is a step toward bringing a just balance of power and resources (i.e., space) in the world. It is an act of radical love.

Why are we constantly apologizing for the space we inhabit? What if we all understood the inherent vastness of our humanity and therefore occupied the world without apology? What if we all became committed to the idea that no one should have to apologize for being a human in a body? What if we made room for every body so that no one ever had to stand on someone else’s foot? How might we change our lives? How might we change the world?

Radical Reflection

Our freedom from body shame demands that we look at how we have perpetuated shame in others. We will need to be radically honest on this journey.

Being a human can feel like a daunting task. It is easy to feel at the whim of the universe. We have been convinced we are ineffectual at exacting any real change against our social systems and structures, so instead we land the guilt and blame squarely on the shoulders of the most accessible party: ourselves. This burden has kept us immobile in our own lives and oblivious to our impact in the world. The weight of the shame has kept us small and trapped in the belief that our bodies and our lives are mistakes. What an exhausting and disheartening way to live. It was this sense of epic discouragement that fueled my inquiry into the nature of apology and led me to explore how our lives might look different if we began living unapologetically. What would the world look like if each of us navigated our lives with the total awareness that we owed no one an apology for our bodies? That exploration into unapologetic living led me to a two-tiered hypothesis. My hunch was, the more unapologetically I showed up in my body, in my community, my job, family, and world, one of two things would happen: either I would pass on to others the power and permission to be their unapologetic selves, or others would feel indicted and intimidated by my unapologetic being and would attempt to contain or shrink me. As the universe often does, it gave me the opportunity to test my hypothesis, in this case on the evening of February 9, 2011.

Six months prior, I had taken a camera-phone picture of myself in a black, strapless corset while getting dressed for an event. I was being saucy, sexy, and silly, and I absolutely did not think a single soul besides myself would ever lay eyes on that photo. For months, I’d catch myself skimming through images of old meals, museum visits, cute shoe fantasy purchases, and then I would happen upon the photo of my dark, wide body in the black corset. Damn, I was hot! And yet, despite feeling vibrant and bold, I was terrified to share the photo with anyone. The voices of apology immediately began a chorus of questions: Would people think I was vain? Would they fail to see the beautiful woman I saw in the image and instead simply remind me that I was too fat, too Black, too queer, too woman, and no one was ever going to think that was beautiful? Unable to answer my litany of shame-based interrogations, the photo remained secreted away in my cell phone, only spied when I needed an esteem boost (see how my self-esteem was floating at sea, buoyed only by a selfie).

A war I could not yet name was raging inside me. It was the war between radical self-love and body shame. On February 9, 2011, a friend posted a picture of plus-size model Tara Lynn on my Facebook wall. Immediately I was taken aback by her gorgeousness and more than a little enamored (read: total crush). Searching her name on Google (a.k.a. Internet scrolling through her pics for hours) returned photo after photo of this stunning woman posing casually in jeans and a crisp white shirt for a trendy department store or wearing nothing but a string of pearls while splayed across a fur rug. But the final photo would be the one to prove at least a portion of my hypothesis. I ran the mouse across the hyperlink, and there was Tara Lynn standing resplendent in a black corset, the cover girl for a new lingerie campaign.21 Her empowered being instantly empowered my being. In one click of a digital image, Tara Lynn gave me permission to be fully seen in my body, opinions be damned! I did in that moment what I had felt completely incapable of doing for months: I immediately posted the picture of me in my black corset to Facebook. Alongside the image I wrote the following caption: “In this picture, I am 230 lbs. In this picture, I have stretch marks and an unfortunate decision in the shape of a melting Hershey’s Kiss on my left thigh. I am smiling, like a woman who knows you’re watching and likes it. For this one camera flash, I am unashamed, unapologetic.”22

Radical Reflection

The voice of doubt, shame, and guilt blaring in our heads is not our voice. It is a voice we have been given by a society steeped in shame. It is the “outside voice. “Our authentic voice, our “inside voice,” is the voice of radical self-love!

Just as Tara Lynn’s unapologetic power permissioned my own, I did the same for others, asking my friends to share photos in which they felt unashamed and unapologetic in their bodies. The next morning I opened my Facebook page only to discover I had been tagged in over thirty photos of people of varying ages, races, sizes, abilities, genders, sexual orientations, and more who had chosen, even if just for that brief minute, to stop hiding and apologizing and instead simply be their unabashed selves. I was consumed. I needed to know the bounds of this unmapped universe where all of us could live in our bodies like we knew we were already okay. Aware that I would need other unapologetic people willing to explore this budding notion with me, I did what any Gen Xer on the cusp of millennial status would do: I started a Facebook group and used it to house these newly sourced unapologetic photos from my friends around the country. The group operated as a geographically unconstrained space where we could practice loving ourselves, our bodies, and other people’s bodies unapologetically. I named the page after a poem I had written right around the time I took that fateful saucy selfie: “The Body Is Not an Apology.” Quickly it became clear that our brief moments of unapologetic living were highly contagious acts—like the flu but much happier!

Being unapologetic created an opening for radical self-love. Each time we chose to embrace the fullness of ourselves, some layer of the body-shame onion got peeled away, evidencing the power of every small unapologetic act. I have been watching this radical disrobing of shame change the world, one unapologetic human at a time. And each moment that I practice living unapologetically I realize my grandma was right: I wasn’t ever actually sorry. When we genuinely love ourselves, there is no need to be.

Unapologetic Inquiry #4

What are you ready to stop apologizing for?

The Three Peaces

From the moment the phrase “The body is not an apology” and the idea of radical self-love fell from my lips, they have echoed as a resounding “Yes!” to those who have heard them. That YES feeling is likely the reason you are reading this book right now. On some cellular level, we know our bodies are not something we should apologize for. After all, they are the only way we get to experience this ridiculous and radiant life. A part of us is a bit repelled by the overt espousal of body shame. It is the reason we whisper and rumor about other folks’ bodies behind their backs. We know our snickers and taunts are wrong. When we are honest with ourselves, we feel gross about the way we vulture other humans, picking apart their bodies, consuming them for the sake of our own fragile sense of self. We feel gross when we think about all the vicious, cruel comments we’ve heard leveled against people’s bodies; comments spoken around us without a single protest from us.

Our best selves find the evisceration of other humans repugnant. We feel shame when we are shamed. And when we allow ourselves, we feel shame for having shamed others. Feelings of shame suck! So, what do we do? Stop shaming people? No. We distance ourselves from the guilt by couching our body judgment in the convenient container of choice. We say things like, “Hey, it’s okay to judge them; they chose to be gay.” “You know you could lose weight if you wanted to!” “It’s not my fault you are a guy dressing like a girl!”

The argument that people “chose” to be this way or the other is at its core an argument about difference and our inability to understand and make peace with difference. The notion of choice is a convenient scapegoat for our bias and bigotries. Logic says, “If people are choosing to be different, they can just as simply choose to be the way I believe they should be.” What we must ask ourselves instead is, “Why do I need people to be the way I believe they should be?” The argument about choice is a projection. There are endless things in the world we do not understand, and yet we live in a culture where we are expected to know and understand everything! Humans are rarely given permission to not understand without someone calling us failures or stupid. No one wants to feel like a stupid failure, and our brains have all sorts of savvy tricks to avoid those feelings.

A particularly strategic maneuver is to decide that if we don’t understand something it must be wrong. After all, wrong is simpler than not knowing. Wrong means I am not stupid or failing. See all that sneaky, slimy projection happening there? Projection shields us from personal responsibility. It obscures our shame and confusion and places the onus for reconciling it on the body of someone else. We don’t have to work to understand something when it is someone else’s fault. We don’t have to undo the shame-based beliefs we were brought up with. We don’t have to question our parents, friends, churches, synagogues, mosques, government, media. We don’t have to challenge or be challenged. When we decide that people’s bodies are wrong because we don’t understand them, we are trying to avoid the discomfort of divesting from an entire body-shame system.

How do we fight the impetus to make the bodies we do not understand wrong? There are three key tenets that will help pry us out of the mire of body judgment and shame. I call them the Three Peaces. They are:

- Make peace with not understanding.

- Make peace with difference.

- Make peace with your body.

Peace with Not Understanding

We must make peace with not understanding. Understanding is not a prerequisite for honor, love, or respect. I know extraordinarily little about the stars, but I honor their beauty. I know virtually nothing about black holes, but I respect their incomprehensible power. I do not understand the shelf life of Twinkies, but I love them and pray there be an endless supply in the event of an apocalypse! When we liberate ourselves from the expectation that we must have all things figured out, we enter a sanctuary of empathy. Being uncertain, lacking information, or simply not knowing something ought not be an indictment against our intelligence or value. Lots of exceptionally smart people can’t work a copy machine. This is not about smarts. Nor am I proposing we eschew information. Quite to the contrary, this is an invitation to curiosity. Not knowing is an opportunity for exploration without judgment and demands. It leaves room for the possibility that we might conduct all manner of investigation, and after said research is completed we may still not “get it.” Whatever “it” may be. Understanding is ideal, but it is not an essential ingredient for making peace. Buddhist teachings tell us that the alleviation of suffering is achieved through the act of acceptance.23 Here is a place where acceptance becomes a tool of expansion. Genuine acceptance invites reality without resistance. Wrong and right are statements of resistance and are useless when directed at people’s bodies. “Her thin body is just wrong” sounds nonsensical because beneath our many layers of body shame, we know that bodies are neither wrong nor right. They just are.

Acceptance should not be confused with compliance or the proposal that we must be resigned to the ills and violence of the world. We should not. But we must be clear that people’s bodies are not the cause of our social maladies. Napoleon was not a tyrant because he was short. Osama bin Laden was not a terrorist because Muslims are predisposed to violence. Our disconnection, trauma, lack of resources, lack of compassion, fear, greed, and ego are the sources of our contributions to human suffering, not our bodies. We can accept humans and their bodies without understanding why they love, think, move, or look the way they do. Contrary to common opinion, freeing ourselves from the need to understand everything can bring about a tremendous amount of peace.

Unapologetic Inquiry #5

What are you willing to stop struggling to understand for the sake of peace?

Peace with Difference

We must make peace with difference. This is a simple perspective when applied to nature, but oh, how we struggle when transferring the concept onto human forms. The late poet and activist Audre Lorde said, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.”24 Think of all the times we have heard some well-meaning person attempting to usher in social harmony by declaring, “But aren’t we all the same?” Here’s the short answer to that: No. We are not all the same, no more than every tree is the same or every houseplant or dog. Humans are a complicated and varied bunch, and those variations impact our lived experiences. The idea that we are all the same is often a mask. It is what we tell ourselves when we haven’t mastered the first Peace. Rather than owning that we don’t understand someone’s experience, we shrink it or stuff it into our tiny capsules of knowledge. We homogenize it by proclaiming we are all the same.

Dr. Deb Burgard, a renowned eating disorders therapist and pioneer in the Health at Every Size (HAES)25 movement, cocreated a brilliant animated video called “The Danger of Poodle Science” to explain body diversity and the perils of assessing health and wellness based on assumptions about size.26 In it, Dr. Burgard details how absurd it would be if we assessed the health of all dogs by comparing them to the size and health of poodles. Better yet, what if the poodles decided that all other dogs should look, eat, and be the same size as poodles? The video pokes fun at our medical industry and its one-size-fits-all orientation toward bodies. Rather than acknowledging and basing research on the premise that diversity in weight and size are natural occurrences in humans, we treat larger bodies with poodle science and then pathologize those bodies by using the rhetoric of health. “I just want this complete stranger, whose life I know nothing about and whom I have made no effort to get to know beyond this Twitter thread, to be healthy.” This is called health trolling or concern trolling, and it is just another sinister body shame tactic. Given that we can make no accurate assessment of any individual’s health based simply on their weight (or photo on social media), it is evident that such behavior is not really about the person’s health but more likely about the ways in which we expect other bodies to conform to our standards and beliefs about what a body should or should not look like. Equally damaging is our insistence that all bodies should be healthy. Health is not a state we owe the world. We are not less valuable, worthy, or lovable because we are not healthy. Lastly, there is no standard of health that is achievable for all bodies. Our belief that there should be anchors the systemic oppression of ableism and reinforces the notion that people with illnesses and disabilities have defective bodies rather than different bodies. Each of us will have varying degrees of health and wellness throughout our lives, and our arbitrary demands and expectations as they relate to the health and size of people’s bodies fuel inequality and injustice.

Not only do such demands perpetuate injustice, much of the “science” put forth regarding weight and health was born out of systems of inequity. In Sabrina Strings’s 2018 release Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia she traces the beginnings of our fear of fat bodies back to the proliferation of Protestant religious dogma in North America and African chattel slave trade, offering that not until theology converged with an influx of African bodies in America did fatness become part of a medicalized public health ideology. She states, “The phobia about fatness and the preference for thinness have not, principally or historically, been about health. Instead, they have been one way the body has been used to craft and legitimate race, sex, and class hierarchies.”27 Start by remembering everyone is not a poodle, and that is okay. Boy, would the world be a boring, yappy place if we all were.

Bodies are diverse not only in size but in race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, physical ability, and mental health. The example of poodle science speaks to a larger issue, one in which our societies have defined what is considered a normal body and have assigned greater value, resources, and opportunities to the bodies most closely aligned with those ideas of normal. When we propose that all bodies are the same, we also propose that there is a standard to measure sameness against. I call this standard the “default body.” Aspects of the default body change across culture and geography, but it shapes our ideas of normalcy and impacts our social values. Our assumptions about the default identities of race, age, ability, sexual orientation, gender, size, and so on become the bedrock upon which societies build body-based oppression. We will explore later how our notions of default bodies developed over time, but for now just know that our propensity to shrink human diversity into sameness creates barriers for the bodies that do not fit our default models. We must move from occasionally celebrating difference (as long as it doesn’t fall too far outside the boundaries of our ideas of “normal”) to developing a difference-celebrating culture. Inequality and injustice rest firmly on our unwillingness to exalt the vast magnificence of the human body.

Radical Reflection

“Celebrating difference” is nice but not transformative. It is constrained by the boundaries of our imaginations. We must strive to create a difference-celebrating culture where we see diversity as an intrinsic part of our everyday lives.

Unapologetic Inquiry #6

In what ways have you tried to make other people “the same” as you? What parts of their identity did you erase by doing this?

Peace with Your Body

Lastly, you must make peace with your body. I have been talking all kumbaya and collective in the first two Peaces, but this one is all on you, love. Your body is the body it is. Your belief that your body should be some other body other than the body it is is likely a reflection of your struggles with the first two Peaces. As I said at the beginning of the book, you did not come to the planet hating your body. What if you accepted the fact that much of how you view your body and your judgments of it are learned things, messages you have deeply internalized that have created an adversarial relationship? Hating your body is like finding a person you despise and then choosing to spend the rest of your life with them while loathing every moment of the partnership. I know that lots of humans stay in loveless commitments. Not only am I proposing that you should not stay in a loveless partnership; I am also proposing that your partner has been set up. If your body were an episode of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, it would be getting framed for crimes it did not commit. Get out of that damn television show and into living in peace and harmony with the body you have today. Your body need not be a prison sentence. And if you are living in it as such, I am glad you picked up this book. As they say in the tradition of twelve-step programs, “You are in the right place.”28

I am not simply proposing that you make peace with your body because your body shame is making you miserable. I am proposing you do it because it’s making us miserable too. Your children are sad that they have no photos with you. Your teenager is wondering if they, too, will be obligated to hate their body because they see you hating yours. The bodies you share space with are afraid you are judging them with the same venom they have watched you use to judge yourself. Remember that body shame is as contagious as radical self-love. Making peace with your body is your mighty act of revolution. It is your contribution to a changed planet where we might all live unapologetically in the bodies we have.

Unapologetic Inquiry #7

Who in your life is most affected by your body shame? How is it impacting them?

I know you may be saying, “But I don’t know how to make peace with my body!” On these pages, together, we are going to help you master the third Peace. The key to getting out of a maze is remembering the way you got in. It’s not an easy task, but this book is an attempt to start at the beginning and show you how you got to the center of body shame. Together we are going to walk back to the beginning and out of the maze. Radical self-love is both the light that will guide us and the gift on the other side.

Radical Reflection

Spend some time reflecting on Chapter 1. Notice what fears or concerns it triggers in you. Notice where there is excitement or joy. Share both with a friend.