Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Change Handbook 2nd Edition

The Definitive Resource on Today's Best Methods for Engaging Whole Systems

Peggy Holman (Author) | Tom Devane (Author) | Steven Cady (Author)

Publication date: 01/01/2007

Bestseller over 35,000+ copies sold

- Features descriptions of sixty-one change methods--up from eighteen in the first edition--and new chapters on selecting a method, mixing and matching methods, and sustaining results

- Describes every change method's essential concepts and processes and provides advice on when to use each

- Including ninety contributors, with many of the originators of the change methods described

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

- Features descriptions of sixty-one change methods--up from eighteen in the first edition--and new chapters on selecting a method, mixing and matching methods, and sustaining results

- Describes every change method's essential concepts and processes and provides advice on when to use each

- Including ninety contributors, with many of the originators of the change methods described

—Margaret J. Wheatley, author of Leadership and the New Science and coauthor of A Simpler Way

“The Change Handbook is about great ideas written from the experience of great people. If organization and community change is what you care about, and hope is what you long for, this book offers a doable path to both.”

—Peter Block, author of Stewardship and The Empowered Manager

“Lots of change management books tell you how things work in theory. This one also shows how the culture change process at GTE and other companies work in practice. It's a good resource for any leader looking for both ideas and proven results.”

—Tom White, senior vice president of market operations, GTE Corporation

Acknowledgments

Introduction and Essential Fundamentals

Part I: Navigating Through the Methods

1. The Big Picture: Making Sense of More Than Sixty Methods

2. Selecting Methods: The Art of Mastery, Steven Cady

3. Preparing to Mix and Match Methods, Peggy Holman

4. Sustainability of Results, Tom Devane

Part II: The Methods

Adaptable Methods

In-depth

5. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change, David L. Cooperrider and Diana Whitney

6. Collaborative Loops, Dick Axelrod and Emily Axelrod.

7. Dialogue and Deliberation, Sandy Heierbacher

8. Integrated Clarity: Energizing How We Talk and What We Talk about in Organizations, Marie Miyashiro and Marshall Rosenberg

9. Open Space Technology, Harrison Owen

10. The Technology of Participation, Marilyn Oyler and Gordon Harper

11. Whole-Scale Change, Sylvia L. James and Paul Tolchinsky

12. The World Café, Juanita Brown, Ken Homer, and David Isaacs

Thumbnails

13. Ancient Wisdom Council, Wind Eagle and Rainbow Hawk Kinney-Linton

14. Appreciative Inquiry Summit, James D. Ludema and Frank J. Barrett

15. The Conference Model, Dick Axelrod and Emily Axelrod

16. Consensus Decision Making, Tree Bressen

17. Conversation Café, Vicki Robin

18. Dynamic Facilitation, Jim Rough and DeAnna Martin

19. The Genuine Contact Program, Birgitt Williams

20. Human Systems Dynamics, Glenda H. Eoyang

21. Leadership Dojo, Richard Strozzi-Heckler

22. Evolutions of Open Systems Theory, Merrelyn Emery and Donaldde Guerre

23. Open Space-Online Real-Time Methodology, Gabriela Ender

24. Organization Workshop, Barry Oshry and Tom Devane

25. PeerSpirit Circling: Creating Change in the Spirit of Cooperation, Sarah MacDougall and Christina Baldwin

26. Power of Imagination Studio: A Further Development of the Future Workshop Concept, Petra Eickhoff and Stephan G. Geffers

27. Real-Time Strategic Change. Robert “Jake” Jacobs

28. SimuReal: Action Learning in Hyperdrive, Catherine Perme and Alan Klein

29. Study Circles, Martha L. McCoy

30. Think Like a Genius: Realizing Human Potential Through the Purposeful Play of Metaphorming, Todd Siler

31. Web Lab's Small Group Dialogues on the Internet Commons, Steven N. Pyser, J.D., and Marc N. Weiss

Planning Methods

In-depth

32. Dynamic Planning and the Power of Charrettes, Bill Lennertz

33. Future Search: Common Ground Under Complex Conditions, Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff

34. Scenario Thinking, Chris Ertel, Katherine Fulton, and Diana Scearce

35. Search Conference, Merrelyn Emery and Tom Devane

Thumbnails

36. Community Summits. Gilbert Steil, Jr., and Mal Watlington

37. Large Group Scenario Planning, Gilbert Steil, Jr., and Michele Gibbons-Carr

38. SOAR: A New Approach to Strategic Planning, Jackie Stavros, David Cooperrider, and D. Lynn Kelley

39. Strategic Forum, Chris Soderquist

40. Strategic Visioning: Bringing Insight to Action, David Sibbet

41. The 21st Century Town Meeting: Engaging Citizens in Governance, Carolyn J. Lukensmeyer and Wendy Jacobson

Structuring Methods

In-depth

42. Community Weaving. Cheryl Honey

43. Participative Design Workshop, Merrelyn Emery and Tom Devane

Thumbnails

44. Collaborative Work Systems Design, Jeremy Tekell, Jon Turner, Cheryl Harris, Michael Beyerlein, and Sarah Bodner

45. The Whole Systems Approach: Using the Entire System to Change and Run the Business, William A. Adams and Cynthia A. Adams

Improving Methods

In-depth

46. Rapid Results, Patrice Murphy, Celia Kirwan, and Ronald Ashkenas

47. The Six Sigma Approach to Improvement and Organizational Change, Ronald D. Snee, Ph.D.

Thumbnails

48. Action Learning, Marcia Hyatt, Ginny Belden-Charles, and Mary Stacey

49. Action Review Cycle and the After Action Review Meeting, Charles Parry, Mark Pires, and Heidi Sparkes Guber

50. Balanced Scorecard, JohnAntos

51. Civic Engagement: Restoring Community Through Empowering Conversations, Margaret Casarez

52. The Cycle of Resolution: Conversational Competence for Sustainable Collaboration, Stewart Levine

53. Employee Engagement Process, Marie McCormick

54. Gemeinsinn-Werkstatt: Project Framework for Community Spirit, Wolfgang Faenderl

55. Idealized Design, Jason Magidson

56. The Practice of Empowerment: Changing Behavior and Developing Talent in Organizations, David Gershon

57. Values Into Action, Susan Dupre, Ray Gordezky, Helen Spector, and Christine Valenza

58. Work Out, Ron Ashkenas and Patrice Murphy

Supportive Methods

In-depth

59. Online Environments That Support Change, Nancy White and Gabriel Shirley

60. Playback Theatre, Sarah Halley and Jonathan Fox

61. Visual Recording and Graphic Facilitation: Helping People See What They Mean, Nancy Margulies and David Sibbet

Thumbnails

62. The Drum Café: Building Wholeness, One Beat at a Time, Warren Lieberman

63. Jazz Lab: The Music of Synergy, Brian Tate

64. The Learning Map Approach, James Haudan and Christy Contardi Stone

65. Visual Explorer, Charles J. Palus and David Magellan Horth

Part III: Thoughts About the Future from the Lead Authors

66. From Chaos to Coherence: The Emergence of Inspired Organizations and Enlightened Communities, Peggy Holman

67. High-Leverage Ideas and Actions You Can Use to Shape the Future, Tom Devane

68. Hope for the Future: Working Together for a Better World, Steven Cady

Part IV: Quick Summaries

Part V: References Suggested by Multiple Contributing Authors

Index

About the Lead Authors

1

The Big Picture

Making Sense of More Than Sixty Methods

Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.

—Albert Einstein

Whole system change methods continue to increase in recognition, variety, and use. The first edition of this book included 18 methods and just a few short years later, there are more than 60 methods in this second edition. This creative explosion provides great opportunities for reaching further into organizations and communities to engage people in making a positive and productive difference.

So, let’s say you need to make a change, you have looked at a variety of methods, and you come across this compendium of more than 60 methods. Where do you start? What’s the difference between one method and another … how do you make sense of them all? How do you speak intelligently about them … helping clients, coworkers, employees, community members, stakeholders, leaders … understand the distinctions? WHAT DO YOU DO? This chapter defines seven characteristics to help you see the whole of the methods available to support your work. These seven characteristics are gathered in a “Summary Matrix” that provides you with a quick, “at-a-glance” way to compare and contrast the methods.

Understanding Options:Seven Characteristics to Consider

Categorizing anything is tricky. On one hand, we strive to simplify our world with models, categories, and taxonomies. On the other hand, simplification limits and potentially undermines the essential concepts we strive to better understand. Classification does not stand alone; it is a starting point for consideration. With elaboration and context, a fuller picture emerges. The framework that follows is one lens into that picture. Coupled with the information in the rest of the book, we believe you will have what you need to make sound choices regarding which method(s) can best help you. The method chapters, quick summaries, and end-of-chapter references offer the means to further investigate the possibilities.

PURPOSE

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, the cat said, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.” Purpose ensures we go somewhere intentional. It answers the questions:What is the focus and aim of our work? What methods are designed to do this? We identified five overarching dimensions of purpose. Planning, structuring, and improving describe processes designed to accomplish a specific purpose. Adaptable methods span these purposes. Supportive processes enhance the work, whatever its purpose (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The Five Dimensions of Purpose

• Adaptable methods are used for a variety of purposes in organizations or communities, including planning, structuring, and improving. This group uses principles and practices that adjust to varying needs.

• Planning methods help people in communities and organizations shape their future together. These methods set strategic direction and core identity through activities such as self-analysis, exploration, visioning, value clarification, goal setting, and action development.

• Structuring methods organize the system to create the desired future. They rely on an effective plan and result in redefined relationships among people and redesigned work practices.

• Improving methods increase effectiveness and create operational efficiencies in such areas as cycle time, waste, productivity, and relationships. Basic assumptions of how the organization works often stay the same, while breakthroughs are achieved in processes, relationships, individual behaviors, knowledge, and distributive leadership.

• Supportive refers to practices that enhance the efficacy of other change methods, making them more robust and suitable to the circumstances and participants. They are like spices in a meal, enriching methods to satisfy the unique tastes of the client. They weave into and often become permanent elements of other methods.

TYPE OF SYSTEM

Who do these methods help? What kinds of people are coming together? How might we think of the system undergoing the change? A simple and useful distinction is organizations and communities.

• Organizations have discernable boundaries and clearly structured relationships that help determine which employees, functions, organizational levels, customers, and suppliers to include in a proposed change.

• Communities are more diffuse, often involving a range of possible participants—citizens, different levels of government, associations, agencies, media, and more. These systems are often emerging entities that exist around a common bond, sometimes based in purpose, sometimes in relationships. Alliances, cities, associations, cohousing groups, and activist rallies are examples of geographic communities, communities of interest, and communities of practice.

EVENT SIZE

Most of the methods employ one or a series of events along the change journey. Though they all focus on whole systems, some engage large numbers of participants at one time, while others involve smaller numbers over time. Still others use technology to bring people together across time and space. What best serves your situation? Size has many implications, both strategic and practical. Do we involve the whole system or a meaningful subset? What facilities do we need? How many people do we include? What are the potential costs per person and how much can we afford? It’s a tough balance to include as much of the system as you can while dealing with the constraints of space, time, and cost.

DURATION

When determining what process to use, time is always a factor. What is the sense of urgency? What sort of pace can the organization or community assimilate? What is possible in terms of how frequently people gather? Whatever the nature of the process, it requires time for preparation, for event(s), and for follow-up. This is often tough to characterize because it is highly dependent on the complexity of the initiative. The contributing authors have given us a range based on how their process is typically used.

CYCLE

Some methods have a natural beginning and ending. Others are suited for a periodic planning cycle, and some become “the way things are done around here.” We have identified the following cycles:

• As Needed. Done to accomplish an intended purpose, these methods are not typically scheduled to be repeated. Sometimes they are used only once; however, they may be used again if a new purpose arises.

• Periodic. Repeated over time, these methods are commonly used for planning processes. For example, repetition may be scheduled every few years.

• Continuous. For some methods, the objective is for the event to cease being an event. The full benefit is realized when the application becomes everyday practice.

PRACTITIONER PREPARATION

People often ask, “How quickly can I get started with using this method on my own?” Some methods are deceptively simple to “just do,” yet there is art and nuance to mastering them over time. Mastery of virtually any process is a lifetime’s work. The more complex the change effort, the more advisable it is to get skilled support. Still, knowing what’s involved to prepare new practitioners provides insight into how quickly and broadly change can spread. Here are the distinctions we offer for getting started as a new practitioner:

• Self-Directed Study. Given a background in group work, with the aid of a book, a video, support from a community of practice (perhaps via the internet), or some in-person coaching, a new practitioner can take his or her first steps independently. Because these practices look so simple, this caution is especially important: Start with straightforward applications!

• General Training. Before attempting this work on your own, attend a workshop or work with someone skilled in the process. In some cases, training workshops offer follow-up field experiences that provide opportunities to work as part of a support team.

• In-depth Training. These methods require a significant investment in training and practice before working on your own. Often, there is formal training, certification from a governing body, and mentoring.

SPECIAL RESOURCE NEEDS

Almost every process involves at least one face-to-face or online event. We’ve asked the contributing authors to make visible any unusual needs for people (e.g., many volunteer facilitators), exceptional technology requirements (e.g., proprietary software or hundreds of linked computers in a room), or other out-of-the-ordinary items or resource-intensive requirements.

All processes require a knowledgeable facilitator or facilitation team. Most face-to-face events require adequate space, breakout rooms, comfortable seating, clean air, good lighting, appropriate acoustics, and supplies (e.g., flip charts, markers, tape). Many online processes require a computer and Internet access. Very large events often require audiovisual support. Beyond these basics, is something special required?

An Interlude: A Tale of Multiple Intelligences

We invite you into a behind-the-scenes story with a cliff-hanger ending:

As we searched for how to communicate the qualitative distinctions among the methods in the book, educator Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences offered an exciting possibility.1 Drawing from neurophysiology, Gardner identified the site location in the brain that correlates with each of the intelligences.2 Just as people have natural gifts in different areas—art, math, music, etc.—we thought, “Why not approach these processes by considering their different emphases among the intelligences?” Characterizing the methods this way could open the door to rich conversations about the relationships among the processes and their fit with the purpose of an initiative or the culture of the organization or community. We could also see the intelligences as useful to practitioners in discerning what methods resonated with their skills and talents.

Excited by the idea, we asked the contributing authors to identify the three most dominant intelligences (in order of dominance) for their method. One or two told us they liked the idea and others told us that they didn’t. Most just responded with an answer. A few identified four or more intelligences and were a bit frustrated that we asked them to limit their choice to the dominant three. Then, as our due date for delivering the manuscript neared, three elders of the field weighed in, flatly refusing to play. Merrelyn Emery put it this way, “I object to it [multiple intelligences] being applied to Open Systems Theory methods because whether you like it or not, it is the human implications that will be drawn from the entry and these methods have been designed to be as nondiscriminating as possible.”

In a separate conversation, Sandra Janoff and Marv Weisbord said, “There is equal opportunity to access all the intelligences in Future Search. Future Search is like an empty bottle. People pour in their experiences, history, aspirations, then seek common ground and act based upon it. What is key is to get the right diversity into the room, that’s what gives the event its rich character. Not the method, nor the facilitator.”

It was the eleventh hour and we faced a dilemma: Include the intelligences or drop them from the book? After our initial consternation, we realized that we were in a situation that brings many people to whole system change methods: a complex subject, deeply held beliefs, and the need to find an answer—fast! We faced a consultant’s worst nightmare: the need to practice our own teachings! Taking a deep breath, we embraced the controversy, knowing that disturbances are a doorway to learning and an opportunity for something innovative to emerge. We then did what we advise our clients to do and revisited our purpose: to support readers in discerning enough about the processes to make useful choices.

We discussed the value of the intelligences in meeting this purpose, and specifically how this lens of the intelligences had already benefited our own work. For example, we realized that the book did not have a single process with rhythmic intelligence among the three most dominant. Steven Cady went searching and found two gems: JazzLab and Drum Café.

Peggy Holman talked about how awareness of the intelligences had immediately affected a gathering she did with Juanita Brown, using both The World Café and Open Space. Together, they consciously brought all seven intelligences into play, creating a powerful, rich experience that continues to ripple in its effect on participants. Did bringing music and movement—intelligences that might not have otherwise been incorporated—matter? It is difficult to say; it is clear that the conference accessed parts of participants that might not have been otherwise present.

As we reflected, Tom Devane pointed out that our use of the intelligences had morphed. We didn’t use them to classify; rather, they served a higher purpose, consciously inviting more of ourselves and our participants into the work. Steven Cady added that inventing and incorporating activities that tap the intelligences was a way to evolve the methods.

Yes, we concluded, the intelligences had something valuable to add, but perhaps not in the way we had originally envisioned, and not without more in-depth exploration among the contributing authors. That, we felt would be a disservice to them, to the field, and to our readers. But how could we bring the value, give it the time needed to “simmer,” and meet our publication deadline?

As often happens when we embrace rather than resist disturbances, we found an innovative answer that we believe accomplishes far more than we originally envisioned. We are convening a conversation at www.thechangehandbook.com among the contributing authors. Our eleventh-hour monkey wrench became an opportunity to meet another desire we had: to create an online space to grow a vibrant community of practice across the many process disciplines. What better way to start than with a meaty, substantive issue? We invite you to visit, see how the story is unfolding, and join in the continuing conversation.

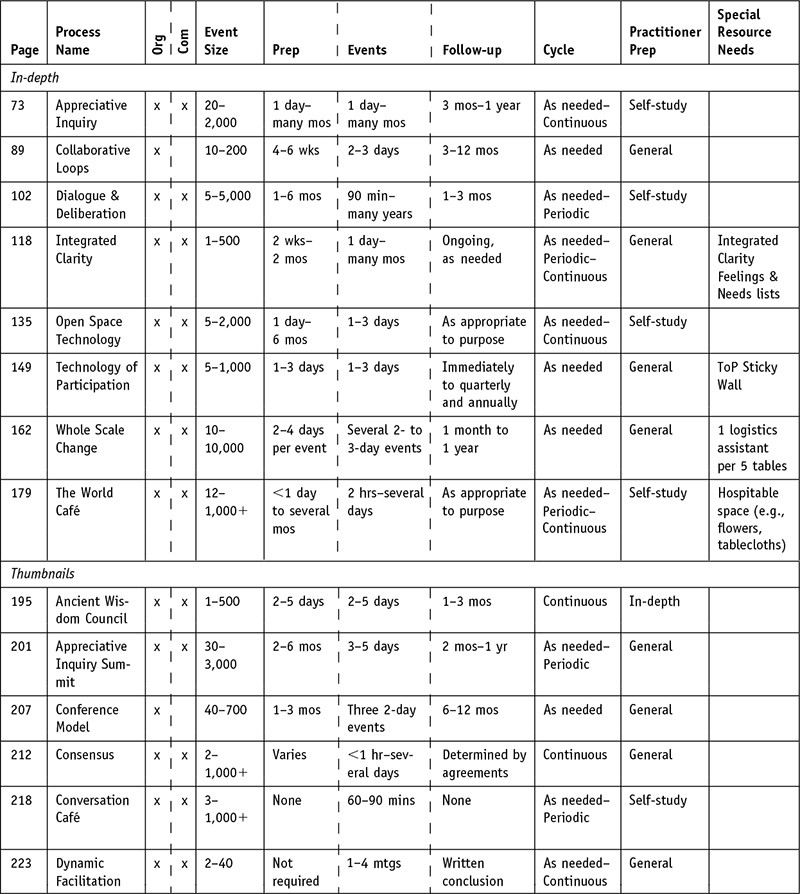

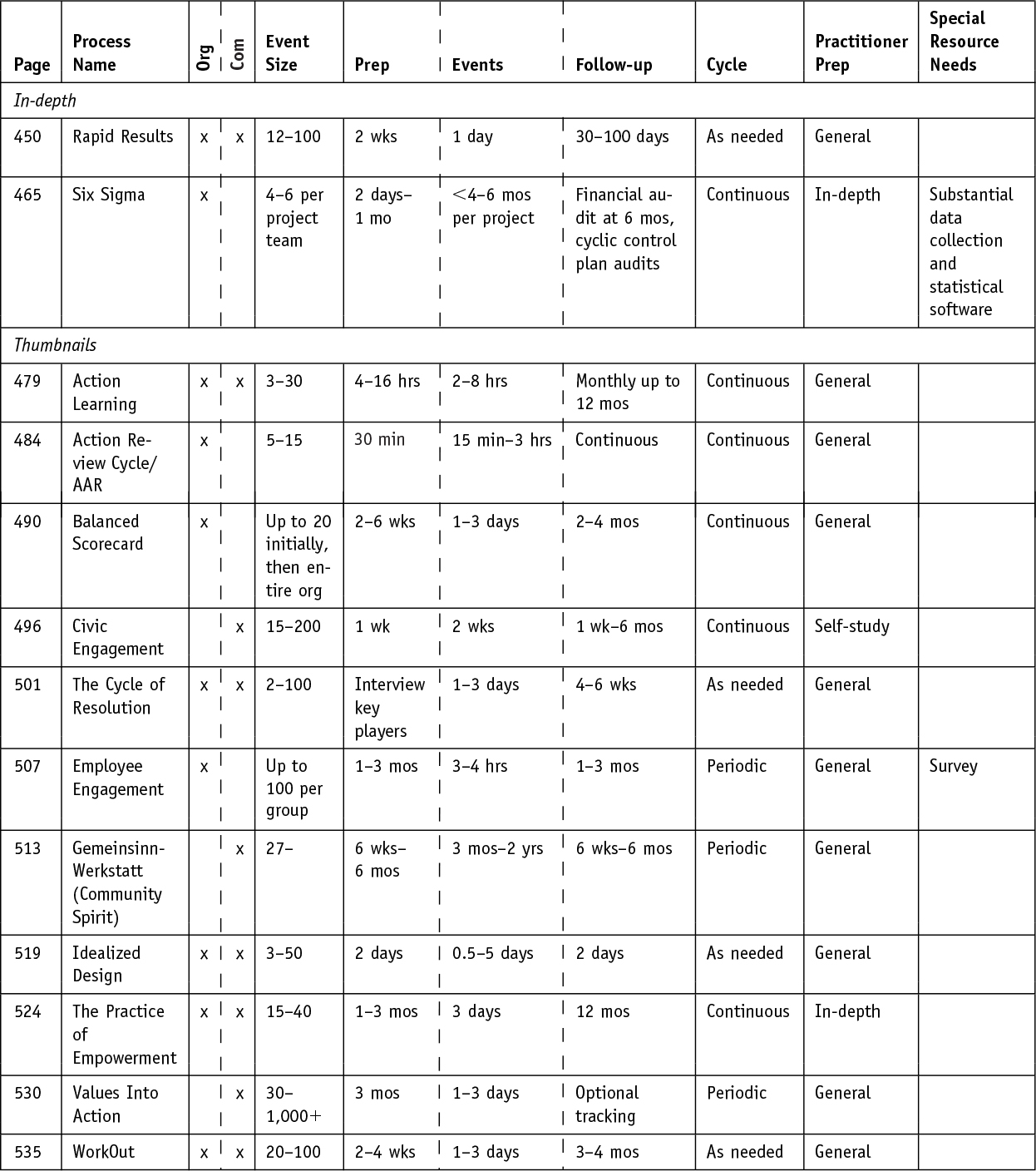

The Summary Matrix

The following tables provide an overview of all the processes in the book. Because purpose is paramount to starting a change initiative, we use it as the primary organizing dimension, with a separate table for each purpose. Within purpose, the in-depth methods are grouped alphabetically followed by the thumbnails, also in alphabetical order. Please note that “Org/Com” abbreviates “Organization/Community.” We hope these tables guide you to the methods that can best serve your needs.

ADAPTABLE METHODS

Adaptable methods are used for a variety of purposes, including planning, structuring, and improving.

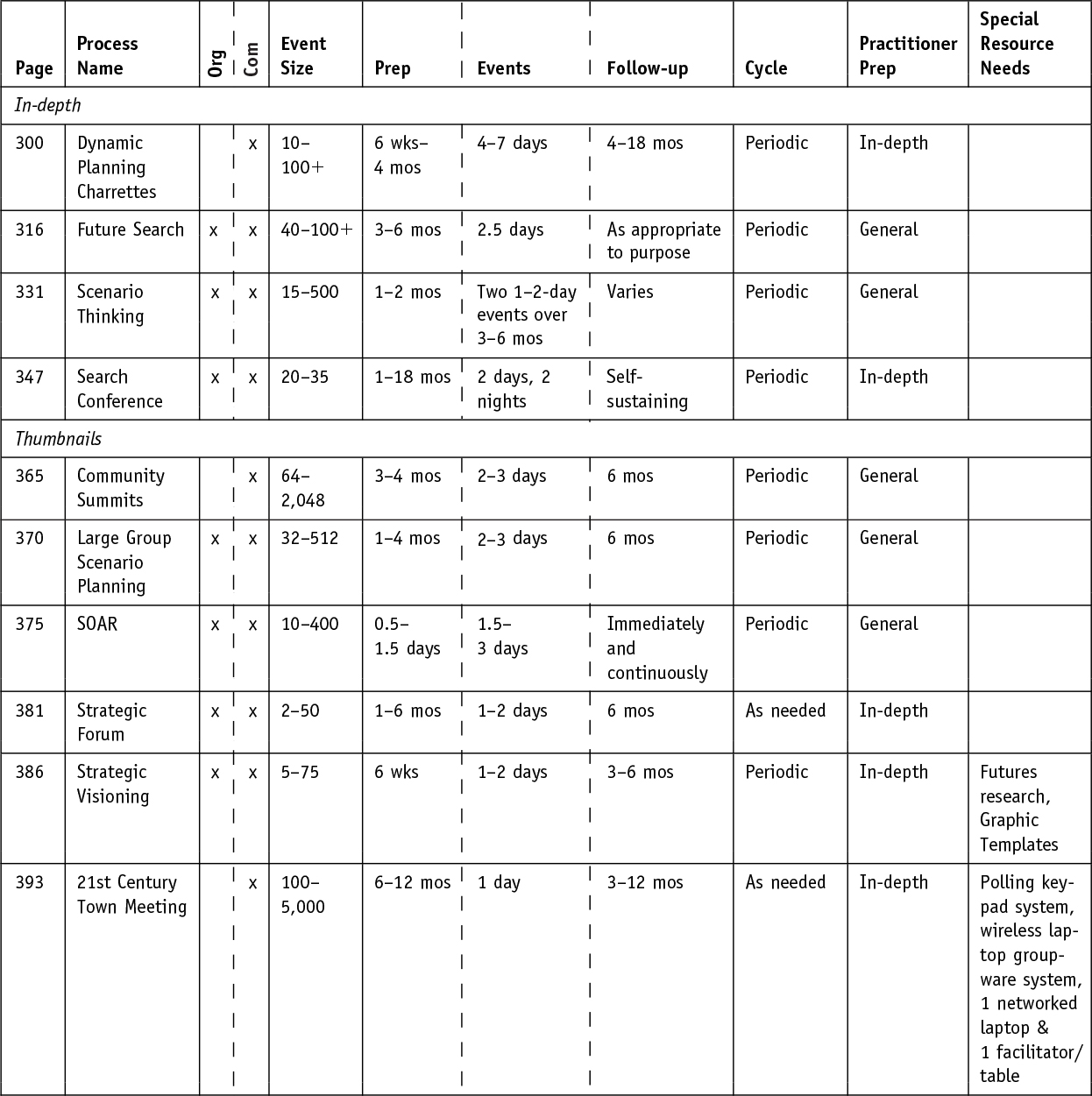

Planning Methods

Planning methods help people shape their future together.

STRUCTURING METHODS

Structuring methods redefine relationships and/or redesign work practices.

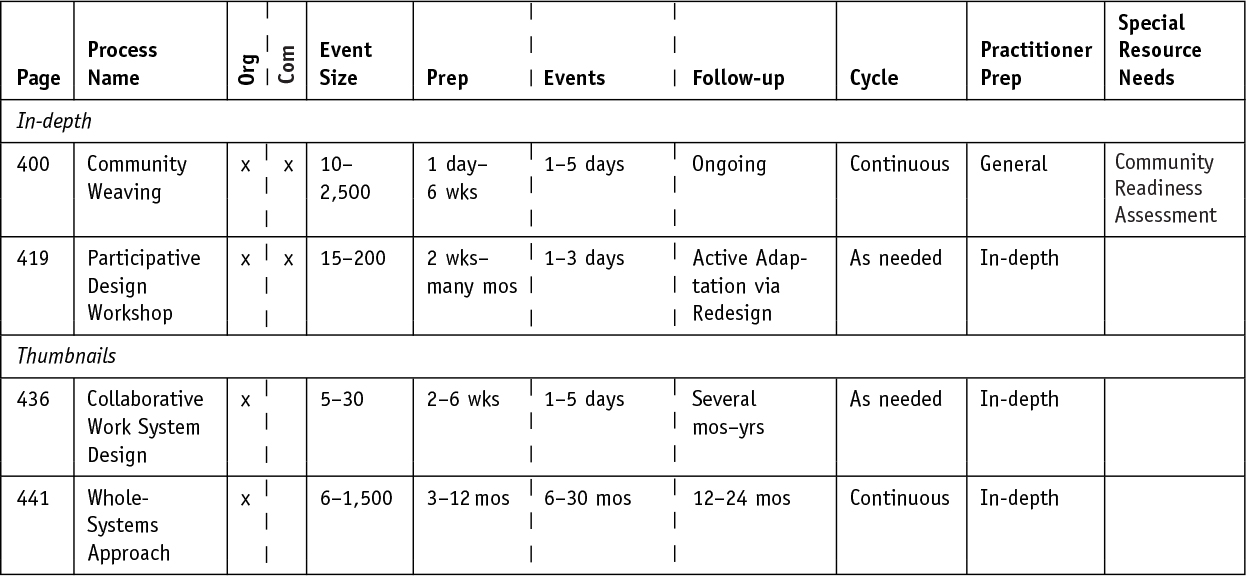

IMPROVING METHODS

Improving methods increase effectiveness in processes, relationships, individual behaviors, knowledge and/or distributive leadership.

SUPPORTIVE METHODS

Supportive refers to practices that enhance the efficacy of other change methods.

1. Gardner’s original seven intelligences are: Linguistic, Logical, Rhythmic, Kinesthetic, Spatial, Interpersonal, and Intrapersonal. For more on their application to whole system change processes, see www.thechangehandbook.com.

2. LdPride (2006). Multiple Intelligence Explained. www.ldpride.net/learningstyles.MI.htm#Learning%20Styles%20Explained; Infed (2006). Howard Gardner, Multiple Intelligences and Education. www.infed.org/thinkers/gardner.htm; Howard Gardner, “Intelligence Reframed,” in Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century (New York: Basic Books, 1999).