Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

The Compromise Trap

How to Thrive at Work Without Selling Your Soul

Elizabeth Doty (Author) | Art Kleiner (Foreword by)

Publication date: 11/01/2009

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

For 27 years, Elizabeth Doty has helped C-Suite leaders improve strategy execution by building cultures of commitment, collaboration and action. Her clients are mission-driven leaders looking to:

- Align Teams for Execution

- Deliver on Brand Promises

- Build Cultures of Commitment, Values and Action

She work with her clients as a partner to help clarify their visions, challenge and inspire their teams and manage follow-through. She brings a candid, fun, results-oriented approach, designing and facilitating high-engagement working sessions with teams, cross-functional work groups and customer partnerships.

In 2016 and 2017, Elizabeth was named a Top Thought Leader in Trust for her work on organizational promises and commitments. She has researched and written on this topic for Harvard University's Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics and for strategy + business magazine. Her book, The Compromise Trap, was published by Berrett-Koehler in 2009.  Elizabeth is also a Certified Partner in Line-of-Sight,™ a Saas approach to pinpointing strategy execution vulnerabilities with blazing speed. She recently joined Prana Business Private Practice, developers of Line-of-Sight™ to assist their clients in addressing issues related to change, engagement and culture. Elizabeth earned her MBA from Harvard Business School in 1991.

Elizabeth is also a Certified Partner in Line-of-Sight,™ a Saas approach to pinpointing strategy execution vulnerabilities with blazing speed. She recently joined Prana Business Private Practice, developers of Line-of-Sight™ to assist their clients in addressing issues related to change, engagement and culture. Elizabeth earned her MBA from Harvard Business School in 1991.

1

The Compromise Trap

You have to interview me again,” said a voicemail from Jim, a sales manager I had interviewed eighteen months earlier when I was beginning my research for this book. “My story has changed.”

Jim was the first of the fifty-two businesspeople I have interviewed over the past four years. These conversations were all part of a quest I embarked on in 2005 to understand how business-people see their personal values connecting to their work.

I met Jim at a conference on sustainable product design, where his company’s innovative carpeting and flooring products were featured (among other things, they made carpet squares that were recyclable). We agreed to meet at a local pub several weeks later for an interview. He arrived almost an hour late, just as I began to wonder if I was insane to venture into such idealistic territory. But then he rushed in, breathless and eager to explain that he was late because he had had the chance to tell his company’s “sustainability story” to a new customer.

“Initially, these interior designers can’t believe they can do something good without hurting their business,” he said. “The idea that they can get cutting-edge flooring designs without all the chemicals that leach into the landfill from broadloom carpeting is electrifying to them. I think it is a relief because they want to do the right thing while meeting their business objectives.” Jim had been slow to get on board with the new product line himself, initially thinking it was just marketing spin. Then he did some research and found out how remarkable his company’s products really were. “Previously, I didn’t understand the issue or what we were doing about it. Shame on me. Now I preach this story every day. I’m on a mission.”

When I asked, as my interview protocol required, whether he ever felt any tension between his personal values and his work, he replied, “It really matters whom you work for. When you work for an employer where your values are aligned, you do not confront those sorts of dilemmas.” He was a subscriber to what I later dubbed the “playing for the good guys” strategy for finding alignment at work.

Now, eighteen months later, his voicemail said his story had changed.

We met at the same noisy pub. As we moved through the crowded room and I swept old peanut shells off the table to make room for my recorder, I could tell that Jim felt a sense of urgency, a need to clean up his story.

“I feel as if I was duped. Just like the movie Who Killed the Electric Car? my company got the pilot teams all excited but didn’t make a full commitment to the sustainability strategy. Now I have tarnished my reputation, selling what they told me to sell, convincing myself they were serious.”

His doubts had begun with a memo. Shortly after he and his family moved cross-country so he could take over as sales director for the new sustainable product lines he had told me about, he received a brief interoffice memo stating that he was required to sell the entire line of products—including the old broadloom carpeting that was the worst offender for landfill.

This caused a minor crisis for Jim. “How could I tell the sustainability story in good conscience if I was pushing broadloom right alongside it? Did they really believe the sustainability strategy they were promoting? Or were we just ‘greenwashing’?” But his leaders assured him that they were actively pursuing ways to reuse the nonsustainable product lines and that the company was firmly committed to more-sustainable products.

So, Jim compromised. He continued telling the “sustainability story” to his customers, assuring them that the company shared his passion for diverting the harmful products going to the landfill and that if they bought broadloom carpeting, there would be some way to reuse it in the near future. But a year went by with little progress on solving the broadloom landfill problem, and gradually the initiative faded from corporate communications. Jim tried to find out the status, asking whether the constraints involved resources, executive support, or technology. “But every time I asked, I got silence,” he said quietly. He looked down for a moment, and the din of the pub intruded on our conversation. I wondered if the recorder would catch his words at this low volume. “To tell you the truth,” he concluded, “I am getting more and more disappointed with how things work.”

Healthy and Unhealthy Compromise

Compromise is a fact of organizational life. You couldn’t get anything done if you did not have some willingness to adapt to the competing priorities and interests that are part of accomplishing any meaningful goal with other people.

Most of the time, compromise is healthy. It is the spirit of compromise that allows people to cooperate to achieve shared goals, allocate scarce resources, smooth over personality differences, leverage diverse points of view, change with the changing world, and learn anything new.

Yet, as Jim found, compromise can be unhealthy too.* When you compromise on something you believe in, it just feels wrong. There is often a strong visceral reaction, like feeling sick to your stomach or having something “stick in your craw.” Perhaps that’s why having “qualms” means having both doubts and a nauseated feeling. Going ahead with these unhealthy compromises takes a bite out of your passion and vitality, leaving you with nagging doubts and uneasiness, regrets and disillusionment, or even dread and deep remorse if severe enough. Jim’s compromise on selling broadloom carpeting left him feeling foolish and guilty, deeply uncomfortable about the false promises he had made to his customers.

On an organizational level, compromising too far can erode quality, lose customers, demoralize employees, damage shareholder value, destroy trust with outside stakeholder groups, and even jeopardize the firm legally and cause great harm to the larger world. A recent news story showed how the agencies responsible for rating mortgage-backed securities made incremental compromise after compromise in their standards until they were touting very questionable mortgages as top quality. During a congressional hearing on the crisis, one representative cried in frustration, “You are the gatekeepers; you are the guys! That’s why you’re there! Now we face a situation where we’ve got a house of cards that has fallen.”1 In this case, compromise contributed materially to the global financial meltdown with which we are all contending.

How does this happen? Greed is too simplistic an answer, especially in an economic system that is supposed to run on self-interest. We all need to better understand the dynamics of unhealthy compromise, the true costs, and what you can do instead without committing career suicide.

But why would you make a compromise that didn’t sit well?

To start with, you don’t compromise if you can have your cake and eat it, too. Compromise is a way of adapting to the pressure created by competing interests, others’ demands and expectations, or circumstances themselves.

The type of pressure you face is part of what leads you to unhealthy compromise.

Healthy and Unhealthy Pressure

Healthy pressure drives you toward healthy compromise. Audacious goals, intelligent strategies, and challenging targets create rewards for pursuing higher priorities and values and/or penalties for pursuing lower ones. They give you a reason to stop squabbling over little stuff and get on with what really needs to be done.

|

Healthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing higher values, wants, and priorities and penalties for pursuing lower ones. Examples: a drive to win new customers by earning their trust, a directive to make cost reductions needed to save the business, or a cultural norm that enforces accountability. Healthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing lower values, wants, or priorities for higher ones. Examples: contributing toward shared goals, sharing costs, deferring projects due to scarce resources, adapting to others’ personalities, or giving up old ways to learn new ones. |

Think of the last great boss you had. Chances are he inspired you by engaging you in a really big challenge. When something is truly important, the natural response is to rise to the occasion, and this involves healthy compromise: putting aside your personal preferences, sharing resources, perhaps putting in longer hours, maybe even relocating with your family as Jim did.

At its core, healthy compromise means adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing lower values, wants, or priorities for higher ones. In other words, it’s giving up something less important to get something more important, just as in negotiations you might make a concession to reach a mutually acceptable settlement.

But as we have seen, pressure at work can be unhealthy as well. It is harder to know how to respond when this happens.

Unhealthy pressure drives you toward making unhealthy compromises. The price of doing the right thing goes up. You still have a choice, but with unhealthy pressure you face penalties for pursuing higher values and priorities and/or rewards for pursuing lower ones. In other words, it becomes increasingly expensive—in terms of energy, political capital, or personal security—to do what you think you should do.

|

Unhealthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing lower values, wants, or priorities and penalties for pursuing higher ones. Examples: expectations that salespeople will lie to customers, a directive to cut costs for appearance’s sake, or a cultural norm that enforces posturing. Unhealthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing higher values, wants, or priorities for lower ones. Examples: agreeing with the boss although you see significant flaws, manipulating numbers to win awards, destroying family relationships to gain a promotion, or overworking until you deplete your health. |

For example, in good economic times when there are plenty of jobs, when your company has an ethics hotline and a culture of high integrity, with senior leadership that walks the talk, it is very difficult but not mortally terrifying to report an unethical boss. But the same situation becomes much more difficult when the circumstances are less supportive—if you don’t know how senior leaders will respond and whether you will keep your job or be able to get another one quickly enough. These are the classic dilemmas faced by would-be “whistleblowers.”

Consider Thomas Tamm, the federal employee who reported a government program he believed carried out unconstitutional warrantless wiretapping on U.S. citizens. As he made the call to report the wiretapping, he realized that some might interpret his actions as treason, a capital crime that could earn him the death penalty. Would he be tried and executed for going public with a civil-rights violation? That’s a pretty high price for doing what he considered the right thing.2

Contrary to popular wisdom, unhealthy pressure at work is not uncommon. Many people I spoke with in my research described situations that pressed them to violate a professional standard, a promise, an important personal value, a personal commitment, or their basic ethics.

For example, an intensive care nurse started having panic attacks after her patient load tripled with managed care. “I was terrified that someone would die on my shift,” she told me, shivering at the thought. A bank loan officer felt cornered into choosing between making unsound loans and losing the respect of her board of directors, who thought her “overly cautious.” Salespeople for a network equipment company confessed their worries to a sales trainer, believing they were supposed to mislead customers by assuring them that every single one of their components was the best in its class, which was not true.

Unhealthy pressure can come from an unethical boss, an organizational culture, a company policy, or even a line of products, as it did for Jim. You may face unhealthy pressure in the midst of an organization you otherwise believe in. The pressure can even come from internal personal issues, as when financial need or an exaggerated drive for the trappings of success leads people to step over the line into cheating, backstabbing, fudging the numbers, or outright fraud or illegal actions. (Of course, you can also have healthy internal pressure such as the desire to do well by doing good.) There is no stark dividing line between healthy and unhealthy pressure; they lie on a continuum of the rewards and the penalties they generate.

Just as the natural response to healthy pressure is healthy compromise, the default response to unhealthy pressure, much as we wish it were otherwise, is unhealthy compromise—giving up something of higher value, like being honest with a customer, for something of lower value, like winning an award. This might mean making a decision that undermines a larger goal, betrays a core value, breaks an important commitment or obligation, or jeopardizes your health or future productivity. For example, playing to the boss’s ego by supporting a shortsighted strategy feels to many people like an unhealthy compromise. Of course, what counts as higher priorities or values varies by person, but everyone has some that are higher and some that are lower, and there is a surprising amount of overlap among us.

The essence of unhealthy compromise is the feeling that you are breaking a commitment to yourself or someone else, failing to protect or live up to a responsibility. This is the sort of compromise that fits the less common dictionary definitions, where compromise means (1) exposing something to danger or suspicion, as when a military mission is compromised, or (2) impairing the health of something, as when an organism is so depleted it can no longer fight off infection. For example, Jim felt he had tarnished his reputation because he had a commitment to serve his customers’ best interests by advising them accurately about his company’s products and in retrospect he had been misleading them about the broadloom product line.

The irony is that most people make these concessions reluctantly.

But what do you do when the pressure is on? Do you dare speak up when you know the boss hates being challenged? What do you do when, like in Jim’s case, a company policy or unwritten expectation requires you to do stupid things that cost the company customers, destroy employee morale, or waste the shareholders’ money?

This is where many people get muddy.

How Shall I Engage?

When the price of doing the right thing goes up, many people feel they have no choice but to conform, especially when their careers or their families’ well-being are at stake. It is particularly challenging when the unhealthy pressure comes from the organization or when others think it is okay to go along. For example, a senior human resources (HR) specialist in a growing technology firm noticed that important decisions were increasingly made with very little thought. She found it harder and harder to ask her colleagues to stop and think before making a decision about whom to hire or where to assign them. “You become the bad guy if you slow things down. I have to use my political capital very carefully.”

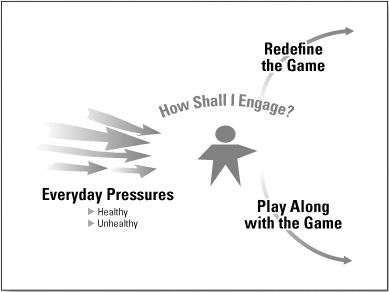

Anytime you face pressure like this, the first question is: How are you going to engage? Are you going to play along with the game, shrinking yourself to fit a bad situation? Or are you going to play big, redefining the game so that you can engage at a higher level? (See figure 1-1.)

Figure 1-1 How Shall I Engage?

Playing along with the game often feels like playing small, “sinking to their level” as some people say. By contrast, when you choose to redefine the game in a positive way, it feels like “being big,” rising above, and bringing the game itself to another level.

For example, Jim in our opening story could now take a narrow perspective, focusing on how to ensure that no one blamed him for unfulfilled promises to customers while turning a blind eye to the company’s shifting priorities; or he could choose to take a broader perspective, focusing on making accurate commitments and, ideally, ones that fulfilled the sustainability story.

According to the conventional wisdom about organizational life, you need to “play the game” to get along and get ahead. Yet it is often precisely this playing along that disturbs people most—whether that means giving lip service to a poor idea, feeling forced to enact a dog-eat-dog mentality, or focusing too much attention on power plays and status rather than the real work and the real value.

Given the intense pressure to play along, it is easy to miss the fact that you do have a choice about whether you accept the terms of the game as defined by others or handed down by history—that is, you have a choice about how to engage.

How you engage refers to the orientation or stance you bring to any situation. You can think of this as the “game” you are playing, in the sense that how you engage determines what you consider a win, whom you include in your thinking, how long a time horizon you project, what questions you ask, what you pay attention to, what options you will consider (and those you won’t), and how you keep score, among other things.3

As a strategy for being true to your values and higher aims, redefining the game means defining a pursuit or an enterprise to be for something rather than against someone. That is what that great boss you recalled earlier was probably doing, in which case, your entire team was probably redefining the conventions of your organization or industry. It is what a breakthrough innovation does and what a true leader accomplishes: setting the terms of engagement at a whole new level.

When you redefine the game, you are engaging at a higher level. You are orienting toward what matters most, considering a bigger win, over a longer time horizon, involving more interests and higher values. Ironically, this means your “game” is about bringing in more of reality and acting as a positive force to help the right thing happen rather than just trying to overcome a threat. It is a far more creative and flexible strategy as a result.

Theoretically, it is possible to convince yourself you have to play along in a negative way even when the pressure is healthy. Those who cross lines for personal gain often feel “this is just how business works,” though they are choosing a very cynical view. I am sure you know someone who feels they have “no choice” but to lie, cheat, steal, or mislead for their personal gain. They are making unhealthy compromises with themselves—betraying their own principles, the company’s values, others’ trust, or even the law—to advance their self-interest. They are solving for themselves, in the short term, and typically count only external measures of success such as money, power, or prestige.

This is what most ethics training is focused on preventing. If that person justifies his actions by feeling he has no choice but to go along with the game, why don’t you do it, too?

Because you made a choice to engage at a higher level than that. At some point you decided to step up to the challenge of actually creating value, of truly winning new customers, of inspiring employees, and of finding more-innovative or more-efficient ways to operate, rather than simply meet your goals or company targets by cheating. That is why you choose the admired company or work for a visionary boss. But can you step up in that way when the pressure turns unhealthy? Can you afford to swim against the current? How do you do it? These are the questions at the heart of this book.*

Without workable answers to these questions, you are likely to feel that your only choice is to play along with the game if the pressure becomes unhealthy. And, based on my research, that is going to lead you into a trap.

The Compromise Trap

The choice to play along with the game in the face of unhealthy pressure is often automatic, a gut-level response to a threat or risk. For example, I distinctly recall sliding discreetly backward in my chair during a meeting where a senior executive was upbraiding a team—just to stay out of his line of sight. It was a gut reaction out of fear that came from worrying only about myself—and not one I am proud of.

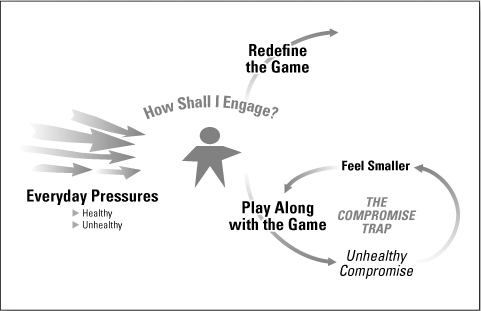

Once you’ve taken that narrow perspective, it looks as though your most viable option is to make the unhealthy compromise required by the pressure you face. Most people feel that the costs of fighting back or quitting are just too expensive, but they fail to estimate the full costs of unhealthy compromise. This path is both self-depleting and self-reinforcing over time, which is why I call it “the compromise trap.” (See figure 1-2.)

Like all traps, the compromise trap offers enticing bait: the promise that you can win or protect yourself if you will just compromise on a few minor scruples. And like all good traps, the catch in this offer is hidden. The catch is this: you play along with the game because you don’t feel big enough to take on the unhealthy pressure, but each unhealthy compromise leaves you feeling even smaller and less capable.

Figure 1-2 Playing Along with the Game

|

The compromise trap The gradual erosion of vitality, passion, and confidence that occurs when you deal with unhealthy pressure by playing along with the game and compromising in unhealthy ways. |

Every time you cross a line or betray a commitment, you take a bite out of your self-respect, your confidence, and your passion for what you are doing. It is mentally, emotionally, and physically depleting to go along with actions with which you disagree.

For example, when Julie, the chief financial officer/chief operating officer (CFO/COO) of a Fortune 500 company, turned a blind eye to some questionable employment practices it “tore her apart.” Eventually, she started getting sick and couldn’t keep up with her responsibilities. Externally, unhealthy compromise undermines your influence, setting precedents with those around you and teaching them to expect you to comply, or costing you allies as you show that you may betray their trust when the chips are down. Finally, as you lose faith in your courage, creativity, and judgment, you become more dependent on external indicators of success, so you are more driven and willing to do “whatever it takes” next time, tuning out the warning signs that might reveal the trap. This is the meaning of the word demoralize: to cause to lose confidence, spirit, courage, or discipline; to confuse or disorient; to lower morale; to cause to lose moral bearings.

For example, Karen, a marketing communications director who struggled with the posturing her role sometimes involved, described feeling more and more driven even as she felt increasingly uncomfortable inside: “I was riding high on the surface but full of dread underneath. I learned to tune out reality, to rationalize to myself.”

The end result is that you become a bit like the monkey with his hand stuck in a hand-trap: he can get his empty hand into and out of the trap, but while clutching the food his hand is too big to fit back through the opening, so he’s starving because he won’t let go of food he cannot eat. To the outside world and your peer group, you may seem quite successful. You may not even be able to see the harm you are doing or the true costs to yourself until you leave the situation. “Life began for me when I left Wal-Mart,” said an ex-manager who agreed to be interviewed for the documentary Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price. “When you’re in the culture, or the cult, you don’t see any other way.”4 As mentioned earlier, this process can envelope entire companies. For example, you might say the rating agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s fell into the compromise trap during the mortgage-lending boom. Caught in a market-share war, each was convinced it had to do whatever it took to win business from the other. Because their business models involved earning fees from the very companies whose securities they rated, they had a built-in incentive to erode their standards. In a recent PBS special, Standard & Poor’s executive Frank Raiter describes the subtle pressure to compromise that infected his agency during the mortgage-backed security boom. “I was amazed at what they [the division charged with rating collateralized debt obligations] were doing. I saw an erosion of standards in the face of pressure to close a deal.”

Another executive, Richard Gugliada, explained that they had no choice. “[We had] no way of obtaining the information we would normally use, so we needed to come up with a shortcut way of doing it. Otherwise the deal would be unratable; it couldn’t be done.” In other words, he felt there was no choice but to act in a way that ultimately led to devastating negative side effects, causing incredible damage to the company, the industry, and, some would argue, the stability of the entire global credit-rating system.5

The point is when you let others define the choices for you, it is easy to miss the larger stakes and what you truly have to lose.

Redefining the Game

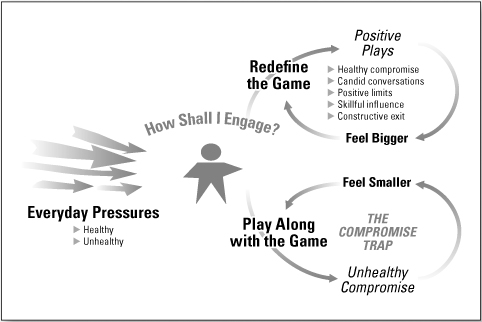

When you are caught in the compromise trap, it feels as though you are selling pieces of your soul but with very few other viable alternatives. Yet a large subset of the people I interviewed actually saw other alternatives and acted on them.

Roughly eighteen of fifty-two people described redefining the game in a positive way in the face of unhealthy pressure, acting courageously to “help the right thing happen” for themselves and others. In the process, they exercised a level of leadership far above their official roles.

For example, Roberta was a young sales director who had gotten on her boss’s “bad side” and found that no one in her office would speak to her, preventing her from doing her job. As her performance ratings slipped, she spent months in worry and self-doubt, yet she stayed because she desperately needed the job. Then one day, thanks to some encouragement from a couple of courageous co-workers, she decided to take a risk. Recalling her strong performance in prior jobs and reminding herself that her goal was to help the company succeed, she walked into her boss’s office and said, “Boss, you cannot treat me this way any longer. This is not okay—it is insulting to me, and it is disabling my ability to create the results I promised you. So, I recommend either I quit today or you start treating me like a member of the team.” She fully expected to be let go, but that’s not what happened. He acknowledged the problem, changed his behavior, and she went on to become one of his top salespeople!

As Roberta’s story shows, redefining the game for the better is not about ignoring hard realities but deciding to be a positive force in the face of them. You bank on your own potential and capability while including other people’s interests in your thinking, considering a longer time horizon, and defining a win in terms of higher values and goals. This is what gives you the courage to engage at a higher level rather than shrink to fit the game you are being pressured to play.

Jim shows us how this can be done even when exiting a situation.

Shortly after our talk in the pub, Jim decided he needed to act on the broadloom issue. First he talked to his family about his concerns and plans. He then went to check out the competition—but with a completely novel approach. “Even though I was just interviewing for a frontline sales management job, I insisted on speaking with the CEO [chief executive officer] and other senior leaders. ‘Are you guys serious? Do you really mean this stuff, or are you full of crap?’ I asked them. I guess I was pretty direct, but I knew I could not sell the product if they were just playing a game. They understood my questions, so they took me through the manufacturing process and showed how the same philosophy was in use there. After several meetings and more tangible examples, I became convinced that it was a real mission and a mindset, not just a marketing pitch. Though they still had things to work on, I could live with it, given that it was a real commitment.”

Meanwhile Jim talked with the leaders at his current employer because he wanted to stay on if they were truly committed to sustainability. He told them he really believed in their mission but he wasn’t sure they were serious and he couldn’t stay if they weren’t. They were polite but didn’t address his concerns, which gave him his answer. Eventually, he moved over to the competitor. He is now thriving as a passionate advocate, speaking at conferences and training his team on all the advantages of the sustainable products. “It is a pleasure to work with these guys,” he told me in a follow-up call. I have a personal suspicion that his graceful way of exiting may have influenced one or more people at his former employer, though we’ll never know for sure.

The people I met who were engaging at that higher level consistently demonstrated this sort of positive approach to negotiating conflicts and dilemmas. They often startled me with the way they thought about things. For example, an HR director described moving closer to difficulty rather than away from it. In describing the greater range of options available when you realize you can redefine the game, one marketing manager said, “It’s almost as if you cross over into a parallel universe; there’s so much more you can do.” And once they had adopted this path, it became self-reinforcing, just as the compromise trap did: each positive play left them feeling bigger and more capable, more able to engage at that higher level the next time. (See figure 1-3.)

Figure 1-3 Redefining the Game

So, what enabled these eighteen people to risk redefining the game in the first place, daring to set their own terms on how they would engage? Were they independently wealthy, with all the freedom many of us dream that will bring?

In a way, yes.

Personal Foundations

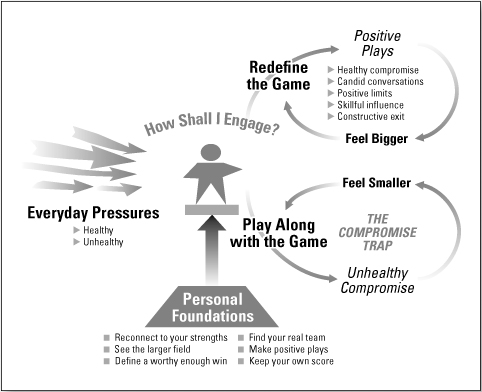

What the people who dared to redefine the game and engage at a higher level had in common was an internal reinforcement system that increased their sense of security, confidence, independence, well-being, creativity, and courage.

Engaging at a higher level under healthy pressure earns you all sorts of recognition and rewards for rising to the occasion. But with unhealthy pressure, when the system creates penalties for doing the right thing, you need additional support to not be drawn off course by the dysfunctional incentives.

So, the first step in strengthening your ability to redefine the game for the better is to switch to your own personal foundations for support. (See figure 1-4.)

In studying patterns in the stories of those who successfully redefined the game under pressure, I identified six personal foundations that make a difference. We explore each of these in depth in the second half of this book, so you can adapt them for your own uses, regardless of the pressure you face.

The Six Personal Foundations

1. Reconnect to your strengths This allows you to access confidence and creativity and provides self-awareness to guide your choices.

Figure 1-4 Tapping Your Personal Foundations

2. See the larger field A broad perspective reveals hidden choice points, costs, and opportunities, so you can be proactive and creative.

3. Define a worthy enough win This gives you a reason for courage and helps you weigh hard choices.

4. Find your real team This provides access to added resources, validation, and support and ensures that your priorities are aligned with your family’s.

5. Make positive plays This gives you a range of options that enable you to be true to yourself while minimizing retaliation; they include healthy compromise, candid conversations, positive limits, skillful influence, and constructive exit.

6. Keep your own score This frees you from comparing with others while providing reassurance of your impact and helping you learn.

With these six personal foundations supporting you, you will have access to a much broader range of options for courageous, constructive action. You will no longer be dependent on your organization for whether you can engage at the level at which you really want to engage.

Thriving at Work without Selling Your Soul

As poet David Whyte once said, “Taking any step that is courageous, however small, is a way of bringing any gifts we have to the surface.”6 Learning to redefine the game in the face of unhealthy pressure means you can not only survive but thrive and contribute in a broader range of circumstances. When you are creatively engaged in pursuing what you are passionate about, even if it is difficult, you feel more alive. Acknowledging the unhealthy pressure leaves you feeling a little more sane, with more access to your creativity and resourcefulness. And when you step up to a higher level of engagement and purpose, you remind others that they have the freedom to do the same—sometimes even those who are pressuring you. A single role model has a dramatic impact on others’ awareness of their choices. It all begins with a decision.

“I decided I was no longer going to cave out of fear,” said a marketing manager after several episodes that undermined her self-respect. “I might have to make hard decisions, but I wasn’t going to cave.”

Suppose you too made the decision not to cave in to unhealthy pressure—or to expand your range beyond your current comfort zone. What support would you need to follow that through?

As you consider that question, in the next chapter, “A Devil’s Bargain by Degrees,” we explore the stories of those who discovered firsthand that the compromise trap is a losing proposition. If nothing else, this should convince you that playing along with the game is not as safe as it may seem.

But first, here is a recap of this chapter’s key concepts, followed by a few reflection questions to connect what we’ve discussed here with your own experience. You may also want to skim “Individual and Small-group Activities” at the back of the book to see the sorts of practical activities we will use throughout our journey.

KEY CONCEPTS

Healthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing higher values, wants, and priorities and penalties for pursuing lower ones.

Healthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing higher values, wants, and priorities and penalties for pursuing lower ones.

Healthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing lower values, wants, or priorities for higher ones.

Healthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing lower values, wants, or priorities for higher ones.

Unhealthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing lower values, wants, or priorities and penalties for pursuing higher ones.

Unhealthy pressure Expectations, demands, or circumstances that create rewards for pursuing lower values, wants, or priorities and penalties for pursuing higher ones.

Unhealthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing higher values, wants, or priorities for lower ones.

Unhealthy compromise Adapting to pressures or constraints by sacrificing higher values, wants, or priorities for lower ones.

Playing along with the game Letting others define the terms of engagement and your options, generally focusing on self-protection or winning as the primary concern. Tends to solve for a narrow set of interests and a short-term time horizon.

Playing along with the game Letting others define the terms of engagement and your options, generally focusing on self-protection or winning as the primary concern. Tends to solve for a narrow set of interests and a short-term time horizon.

Redefining the game Consciously choosing to engage at a higher level, orienting toward whatever matters most, considering a bigger win, over a longer time horizon, involving more interests and higher values as well as practical outcomes. Generally tries to act as a positive force to help the right thing happen, for oneself and others.

Redefining the game Consciously choosing to engage at a higher level, orienting toward whatever matters most, considering a bigger win, over a longer time horizon, involving more interests and higher values as well as practical outcomes. Generally tries to act as a positive force to help the right thing happen, for oneself and others.

The compromise trap The gradual erosion of vitality, passion, and confidence that occurs when you deal with unhealthy pressure by playing along with the game and compromising in unhealthy ways.

The compromise trap The gradual erosion of vitality, passion, and confidence that occurs when you deal with unhealthy pressure by playing along with the game and compromising in unhealthy ways.

Review figure 1-4, Tapping Your Personal Foundations, which graphically summarizes all the concepts covered in this chapter.

Review figure 1-4, Tapping Your Personal Foundations, which graphically summarizes all the concepts covered in this chapter.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Find a copy of your résumé and read back through your work history. What thoughts, feelings, or images come up as you recall each role and organization? What sort of healthy pressures do you recall? Where and when did you feel unhealthy pressure? How did you respond to it? Notice how thinking about these affects you mentally, emotionally, and physically.

Find a copy of your résumé and read back through your work history. What thoughts, feelings, or images come up as you recall each role and organization? What sort of healthy pressures do you recall? Where and when did you feel unhealthy pressure? How did you respond to it? Notice how thinking about these affects you mentally, emotionally, and physically.

What pressures in your current circumstances might lead you to make an unhealthy compromise? Why? How would you like to redefine the game if you could?

What pressures in your current circumstances might lead you to make an unhealthy compromise? Why? How would you like to redefine the game if you could?

Recall a time when you chose to redefine the game in the face of particularly challenging unhealthy pressure. How did you feel just before you took action? What enabled you to take that path? How did you show up differently from normal? What happened as a result?

Recall a time when you chose to redefine the game in the face of particularly challenging unhealthy pressure. How did you feel just before you took action? What enabled you to take that path? How did you show up differently from normal? What happened as a result?

Honesty

Honesty