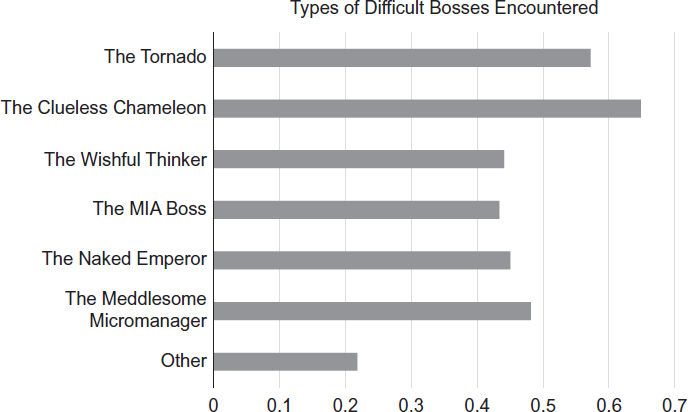

To research the concept of managing up—and managing the difficult boss in particular—my company, Professionalism Matters, launched an online survey asking a wide range of professionals to share feedback (anonymous) on their managers, particularly the difficult ones. I was somewhat afraid I’d get crickets, to be perfectly honest. I’m well aware that employees are often very reticent about providing candid feedback on their experiences with their own leadership. I was truly blown away to receive 1,173 completely organic, candid responses from real people working real jobs that we can all relate to. While the empirical data was fascinating—confirming my suspicions in several areas, providing surprising results in other areas, and overall unlocking and unleashing immensely valuable practical advice—the anecdotal feedback was priceless. It was the type of feedback and advice you’d typically only get from a circle of really close friends sharing the unspoken rules that most people won’t explicitly tell you (often until it’s too late). In my experience, it’s the water-cooler side conversations or frank admissions over a cocktail with a dear friend after a particularly hard day that are the golden nuggets of advice that too many employees never get (or get too late in their career). These “rules” that you typically can’t find in a training class or a new employee orientation are invaluable, so without further delay, let’s dive right in to share some of the survey results.

Survey feedback clearly confirmed that difficult bosses are indeed prevalent (see Figure 1.1). When asked How often have you experienced “difficult bosses” or “difficult senior leaders” over the course of your work history? over 36 percent of survey participants responded “Often” or “Always.” Ouch! That’s more than one in three participants indicating that they’ve experienced difficult bosses not occasionally or rarely but frequently! Over 50 percent selected “Sometimes.”

Anyone who has supported different leaders or executives in some capacity would agree that the concept of a “difficult boss” is a relative term. Indeed, one typically tends to assess a particular boss’s level of “difficulty” in part based on their experiences with other bosses or one’s personal preferences or expectations. As we consider the concept of managing up, it is important to not take a monolithic approach; instead, recognize that managing up techniques should be customized to each individual situation. As much as we might wish there were, there are no silver bullet techniques that work for every manager and situation. This book provides a range of specific, practical techniques that can be used to address a wide variety of situations. Specifically, the book addresses two of these three different types of organizational/managerial realities:

• Red alert situations—when managing up techniques alone are typically insufficient and alternate action or additional support is needed

The first situation is the easiest to handle, so although we will explore many applicable techniques for managing up with the average to strong boss, we focus first and primarily on the most challenging situations—how to handle the dreaded difficult boss. We’ll come back to general tips for managing up with an average to strong boss toward the end of the book, but I’d like to preview some of these fundamentals that can provide a foundation for handling the more delicate and challenging difficult boss situations.

|

Tip #1

|

Build relationships before you need them.

|

|

Tip #2

|

Be likable and low maintenance.

|

|

Tip #3

|

Be a star where you are.

|

|

Tip #4

|

Customize your behaviors to fit your boss’s preferred work and communication style.

|

|

Tip #5

|

Always think three steps ahead. Think strategically.

|

|

Tip #6

|

Look for opportunities to take things off their plate.

|

Indeed, the deliberate emphasis on the difficult boss situations should not be construed as a suggestion that managing up only applies to difficult bosses—on the contrary, the skills and techniques are powerful for great boss situations as well. In contrast, the last situation is beyond the scope of this book. The true “red alert” situation can’t typically be addressed through managing up techniques, so we will touch on some of those situations briefly to help point you in the right direction for additional support (more on this later).

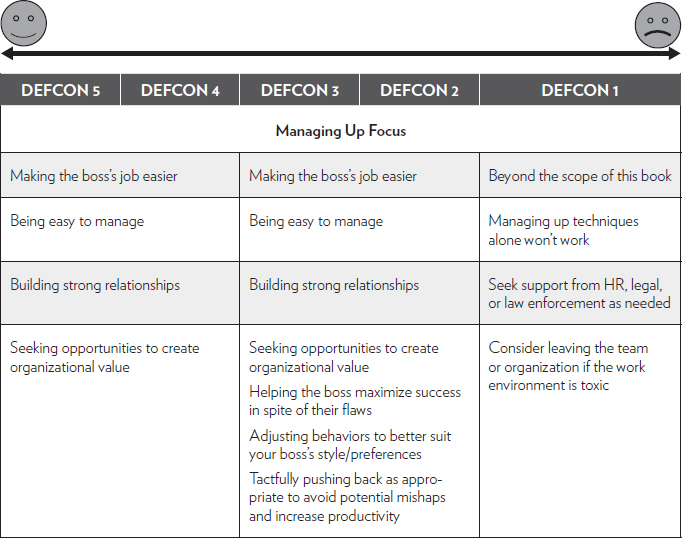

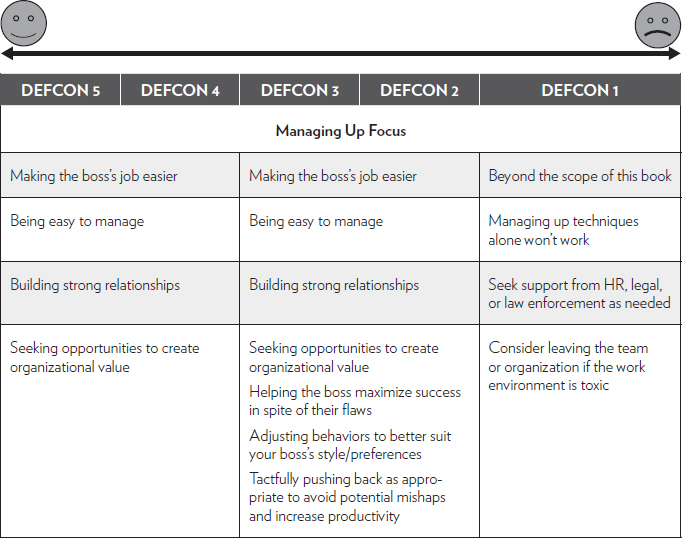

Considering the wide range of managerial realities, I’m reminded of the infamous DEFCON (short for defense readiness condition) scale that measures the nation’s level of defense forces alertness. DEFCON 5 represents a normal state of peace where US forces are at the lowest level of readiness, and the level numbers decrease from there with increasing levels of defense readiness (preparation for possible war). DEFCON 1 represents the highest state of alert (the worst-case scenario).

This DEFCON scale has always reminded me of the workplace. At times, I’ve enjoyed workplace bliss (DEFCON 5/4), but there have been other times when the environment became quite difficult and challenging (DEFCON 3/2), and I had to dig deep into my arsenal of techniques to try to emerge victorious (or at least without a ton of shrapnel wounds). As such, the tactics outlined in the book should always be customized to the individual workplace situation and level of organizational dysfunction and toxicity. Figure 1.2 outlines the basic managing up focus for a range of different organizational environments. Note that the recommended managing up focus for the great situations (DEFCON 5/4) are also applicable for more challenging situations (DEFCON 3/2). However, the more challenging environments require advanced, more specialized techniques as well; hence, the decision to focus primarily on those situations.

WHAT ABOUT THE DEFCON 1 SITUATION?

This book provides great tools and techniques to manage up with DEFCON 5/4 great bosses and the DEFCON 3/2 flawed bosses, but we don’t specifically address the worst-case scenario: the DEFCON 1 bosses or workplace environments. And we exclude them from the scope of this book for good reason—because managing up strategies alone typically won’t work, and it would be a disservice to the reader to suggest otherwise. In my view it would be akin to recommending vitamins to treat a broken bone. Indeed, this situation reminds me of calling my kids’ pediatrician. The voice response system always starts with something like “If you’re experiencing a life-threatening emergency, please hang up and call 9-1-1.” So that’s my message—if you find yourself in a true DEFCON 1 situation, put the book down and seek help immediately!

Figure 1.2 Customizing Managing Up Focus/Tactics for Your

Organizational Environment

While these DEFCON 1 situations are clearly beyond the scope of this book, I would like to take some time to address DEFCON 1 bosses. They’re out there and, unfortunately, some readers may encounter them during their careers.

First, let’s define what we mean by DEFCON 1 bosses. We’re referring to managers (or senior leaders) who are engaging in toxic or severely dysfunctional behaviors or who possess other deeply disturbing personality or character traits. Examples include the following:

• Sexual harassment or inappropriate sexual behavior

• Overtly racist or misogynistic behavior

• Violent or abusive behavior

• Illegal acts

• Clearly volatile, seemingly emotionally or mentally unstable behaviors

• Blatantly lying or misrepresenting material facts consistently

• Seeming to lack any moral compass

• Overtly sabotaging others’ success

• Acting out of a personal vendetta

• Intentionally encouraging a toxic or dysfunctional environment

• Suffering from alcohol or substance abuse

• Completely inept, incompetent, or otherwise dangerously ineffective leadership

These activities and traits are well beyond the boundaries of expected management behavior, and as a result, managing up techniques alone won’t likely address or improve these situations. Managing up is about helping flawed, mediocre, and good managers be more effective. Managing up isn’t a magic potion that will fix irreparably broken or terribly flawed individuals. Those types of deficiencies are often caused by issues well beyond the professional environment and often require professional attention for long-term improvement.

Our managing up survey respondents (unfortunately) shared many examples of working with DEFCON 1 situations/bosses:

• “I had a boss that was so patronizing, micromanaging, and undermining that I took my first ever stress leave in 16 years of corporate work. I lasted two years, quit, and had nightmares about him for the next 18 months. He was fired two years after I left.”

• “One boss would swear at and demean me in front of customers. He did this to most of the employees—an equal opportunity bully. Sadly, there was no conversation, just yelling and scolding.”

• “How about a drunk, seriously. Started drinking when he got to work instead of after.”

• “The unethical boss who expects you to cheat.”

• “Two were downright evil. No morals, very sociopathic. Most were insecure, bad communicators, used subordinates as scapegoats for their mistakes. Never took responsibility.”

• “I also have bosses who send you down one path and when things do not go as expected pull the rug out from under you and let the bus hit you rather than them.”

• “My second boss, the difficult one, was all of the above and had a sycophant right hand. Blew through at least 19 employees in about 1.5 years. Human Resources nicknamed our department ‘Survivor.’”

• “You can’t ‘swing a dead cat’ without hitting a functional psychotic (boss) in the field of PR/marketing.”

• “In a long career in journalism and publishing, I’ve worked for certifiable lunatics.”

Survey respondents also shared how they handled some of these extreme DEFCON 1 difficult boss situations:

• “In one situation, I found a new job. I realized that ‘hateful’ and I do not mix well.”

• “Just keep doing my job as best as I can and then eventually the boss’s antics are outed. Or do the best job you can while looking for another position.”

• “It’s important to understand the difference between accommodating another personality and being the victim of abuse. Some things you can manage by adapting your behavior. Other things may require intervention to halt the abuse. Seeking help from a third party is another possible course of action.”

• “Leave organization when their behavior becomes irreparably self-destructive and harms you personally.”

Many survey respondents indicated that the situations were resolved by them choosing to leave the organization or the manager being terminated. The reality is that if subordinates find themselves dealing with the aforementioned DEFCON 1 type behaviors, the most appropriate course of action may likely involve engaging human resources, employee assistance programs, legal support, or even law enforcement as needed. It’s also important for subordinates to remember that if they are unfortunately experiencing an abusive or toxic work situation, they’re not at fault, so it’s not their responsibility to fix it. Instead, they should focus on seeking appropriate support within and/or outside the organization and ultimately find a healthier environment.

Indeed, when considering the “difficult boss” label, we must also acknowledge a range of personalities and levels of severity. On the extreme end (DEFCON 1), there are fully dysfunctional bosses who certainly earn that pain-in-the-ass reputation. I’m reminded of a colleague who called me one day in a whisper of a voice to ask if it was normal for a boss to berate you for stopping to eat during the day. When I told her that sounded crazy, she told me she had to hang up because she needed to run to the vending machine to try to sneak a bag of chips before her boss came back. That’s a clear case of extreme dysfunction (and possible abuse), and those DEFCON 1 type personalities and situations are not the ones we’re referencing when we talk about the difficult boss.

DIFFICULT IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Labeling people is always a risky proposition (and often problematic). As a corporate trainer with an admitted bias toward pragmatism, I freely admit that I’ve prioritized relatability and practicality over political correctness with the liberal use of the “difficult boss” label. While it’s completely true that there’s no scientific formula or clinical test for determining if a manager is indeed “difficult,” it’s also true that, like obscenity, we typically know it when we see it, so I do freely use the term “difficult boss” throughout the book. I also acknowledge playing somewhat fast and loose by using the terms “boss,” “manager” and “leader” somewhat interchangeably. I certainly recognize the functional differences between managers and leaders, for example, but in this book the terms are used interchangeably because our interpretation of “up” in “managing up” is more broad and generic, referring to anyone holding a higher position hierarchically or with more power in the organization.

It’s also important to acknowledge that what constitutes a difficult boss is often a function of one’s perspective and work ethic. I’ll take myself as an example. Having started a corporate training/speaking business that I named Professionalism Matters more than fifteen years ago, it should come as no surprise that I’m an admitted overachiever with a really high work ethic. I believe great employees work while they’re at work, have a positive attitude, are willing to go the extra mile, respond quickly to emails, and focus on improving themselves continuously. I don’t expect perfection, but I certainly have high standards (that I hopefully model as well). Over the years, I’ve had many assistants (of varying quality, in my opinion). I would venture to guess that my best assistants would describe me as someone with high standards but very fair and good to work for. My not-so-great assistants might characterize me as not just difficult but downright crazy! For example, I’m sure that the assistant I sent home for coming to a client meeting dressed for a tennis match still thinks I’m a real jerk, but that just illustrates the reality that difficulty is in the eye of the beholder and very dependent on one’s perspective. If every single boss you’ve had over the past several years seemed difficult to you, the problem may not be them at all … it might be you! So when we talk about difficult bosses, we’re not talking about bosses with high standards, a high work ethic, or unwavering principles. Those are the good ones! We’re talking about bosses who have flaws or personality quirks that get in the way of their success and yours … and by the way, that’s a lot of them.

ORGANIZATIONAL DYSFUNCTION IS OFTEN ROOTED IN POOR COMMUNICATION

Part of the problem that I’ve observed in the workplace is a tacit “us vs. them” mentality. There are senior leaders at the top—some skilled leaders, others more fledgling/struggling leaders—and then there’s the staff working for them. Those working for the difficult bosses are often suffering in silence or living a horrific workplace experience filled with tension and anxiety, in part because there’s little honest communication taking place between the two groups. Staff often feel powerless because they don’t get to make the decisions, but they have to produce the results. On the other hand, the leaders feel significant pressure due to their level of responsibility and are frustrated by staff who may not produce the desired results. To make matters worse, these leaders must typically rely on staff to get the work done, so (ironically) their level of control often feels more tangential or indirect, and that can cause its own uncomfortable anxiety.

Managers and subordinates often have wildly different perspectives on a project, task, or issue, and those different perspectives can have a huge impact on how they interpret the same situation. Consider the following scenario:

January 15

Manager Mike: Hey, Jim, do you have a minute to chat while I run to this meeting? I’m going to be traveling a lot this quarter, and we need to come up with a solid business plan for the new online training service. You’ve got a deep business background. Could you head that up for us?

Jim: Sure, of course! Thanks for thinking of me, Mike. I’ll get right on it!

Mike: Great, I’m out next week, but let me know if you run into any problems.

January 20

Jim (working at computer, deep in thought): What is he really looking for? Does heading it up mean I’m on the hook for this completely or do I have a team to work with? I wonder what this will be used for? How much time do I really have? I’m assuming he’s looking for an initial high-level plan… nothing too detailed, right?

February 15

Sally (knocking on Jim’s door): Hey, busy?

Jim: Not really, just working on a business plan for Mike, but I’m struggling, to be honest. Can I pick your brain?

Sally: Sure!

Jim: Do you have an idea of what he would typically want in a business plan?

Sally: Who knows? Your guess is as good as mine!

Jim: Maybe I should ask him to spell it out a little more?

Sally: It’s up to you, but I’ll just tell you that Mike is the type of boss who wants you to take something and run with it. He’s not a hand-holder. If he asked you to take it, he probably doesn’t have time for a lot of back and forth. He probably just wants it done.

Jim (answering his phone): Yes, Mike, I was actually just working on that business plan. I’ll bring what I have right over.

Minutes Later in Mike’s Office

Mike: Hey, Jim, sorry I haven’t been around much, but I’m glad you had plenty of time to work on that business plan. Oh, did you reach out to Gail in marketing to incorporate the social media plans? I want to be sure those are in there, but I’m sure you thought of that already. I don’t want to steal your thunder.

Jim: Actually, no, I didn’t realize you wanted to include that. I wasn’t exactly sure what you were looking for, so I developed a basic projection of future earnings from the online training service. I really just focused on those financial projections.

Mike: Tell me you’re kidding! I wanted a full-blown business plan–vendor options, benefits, costs, market analysis, sales strategies … the works! You’ve had a month to get it done! I just assumed you’d pulled a team together to get this finished by now. I’ve got to present it to the CFO this week. Is this all you have?

Jim: I wasn’t sure how detailed you wanted it to be. I have a better understanding now. I’ll drop everything and work on this nonstop and show you what I have by close of business tomorrow.

Later that Day

Mike (in his office, deep in thought): I can’t win! I empower people–give them responsibility, latitude, don’t micromanage, and it blows up in my face. Unbelievable! Now I’m going to look like an idiot in front of the CFO. Jim–what a pain in the ass!

Jim (in his office, deep in thought): I can’t win! I take a thankless task with no direction, no support, no clarity, and when I don’t read his mind, I get raked over the coals. Unbelievable! Now I look like an idiot! Mike–what a pain in the ass!

This vignette illustrates the all too common reality that “difficult” is often a matter of perspective and a byproduct of poor communication between leader and subordinate.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DIFFICULT BOSS

So, who is the difficult boss exactly? Virtually everyone who manages people has likely been the difficult boss at one point or another. There are a few naturally gifted leaders with a rare talent for providing flawless direction, making the best decisions, listening intently, and making team members always feel valued. But my experience is that in the real world one is much more likely to encounter mediocre leaders who are fundamentally good people with honorable intentions but have a tendency to fall into difficult boss behaviors from time to time (or find a more permanent home there). I can certainly relate because I’m sure I’ve been the difficult boss at different times in my career. Indeed, in my opinion the “difficult” in the difficult boss isn’t referencing some deep character defect; instead, it more often refers to skewed behaviors that many managers fall victim to due to their unique perspective (given their more senior station in the organization), a myopic focus on certain interests or priorities (to the detriment of others), and less-developed leadership abilities and/or social skills, among other factors.

The managing up survey certainly confirmed that if you’ve had your fair share of difficult bosses, you’re not alone (and not crazy). Here are just a few of the difficult boss descriptions that participants shared:

• The Mood Monster. “I had one boss that was so temperamental, we would gauge how he reacted to being told ‘good morning’ as a barometer of whether we could approach or avoid him for the day.”

• The Snake. “Constantly slithering around wherever it’s most convenient, and shedding their skin whenever a situation doesn’t suit them.”

• The Fretter. “Creates and demands unnecessary and meaningless tasks.”

• The Antique. “Refuses to learn new methods, adapt to new technology, or address emerging trends.”

• The Narcissist. “Everything is about them, and everyone is a competitor, including their subordinates.”

• The Flying Monkey. “Flies in briefly, changes everything, creating chaos, flies out again.”

• The Never Happy. “No matter the success you achieve, they find something wrong with it.”

• The Martyr. “The one who won’t take leave, even sick leave, and doesn’t like it when others do. This person ignores HR and runs their team into the ground.”

• The Instigator. “They set their direct reports up to work against each other and then they enjoy watching the fireworks.”

• The Incompetent Idiot. “Always in above their head while still holding a position of power. Often not as qualified as others beneath them. Makes those with vision, skill, and ambition wonder how and why they’re in said position of power, while others flounder under their incompetence and misguided direction.”

• The Hoverer. “The manager who would step in when my manager was out of the office and hover over my desk. I found it incredibly distracting and uncomfortable.”

• The Micromanager. “Giving you direction, then going directly to your staff/team and giving direction that was yours to give. You’re the CEO, so why are you hovering over my desk while I’m writing an email to a customer?”

• The Hot/Cold Boss. “One day you are golden, the next he’s yelling obscenities for the same task.”

• The Troll. “Questioned my work habits: ‘Why are you always on the phone?’ when I managed an entirely remote team of eight engineers responsible for global projects. Reviewed what were (in his view) my team’s past mistakes, in the hallway in front of my peers.”

• The Control Freak. “Micromanages, doesn’t share information about the end goal or new insights because he doesn’t think you need that info. You do what you are told—his way.”

When asked to share their best managing up techniques, many commented on the need to proactively document conversations, anticipate needs, customize communication style, and suggest alternative courses of action when necessary. Clearly, the feedback reflects a proactive desire to find ways to best work together for the greater good of the organization—not some fixation on trying to control or manipulate authority. While these comments reflect the participants’ personal opinions and experiences, they may not be appropriate for your specific situation. Have no fear—we’ve outlined a wide array of techniques in the following chapters that you can add to your personal arsenal and customize to address your specific situation:

Chapter 3: Managing the Tornado

Chapter 4: Managing the Wishful Thinker

Chapter 5: Managing the Clueless Chameleon

Chapter 6: Managing the MIA Boss

Chapter 7: Managing the Meddlesome Micromanager

Chapter 8: Managing the Naked Emperor

My hope with this book is that we’ll not just equip the average worker with specific tools and techniques they can use to better manage the difficult boss, but we’ll also remove the stigma or misconceptions around the “difficult boss” label. Many readers will start to recognize some of those difficult boss tendencies within themselves and hopefully begin to reverse some of those unhealthy behaviors. Creating a sense of better understanding between bosses and workers is such an important step in breaking down those toxic hierarchical barriers that hold organizations and individuals back.