Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Transformative Scenario Planning

Working Together to Change the Future

Adam Kahane (Author) | Kees Van Der Heijden (Foreword by)

Publication date: 10/15/2012

Transformative scenario planning is a powerful new methodology for dealing with these challenges. It enables us to transform ourselves and our relationships and thereby the systems of which we are a part. At a time when divisions within and among societies are producing so many people to get stuck and to suffer, it offers hope-and a proven approach-for moving forward together.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

Transformative scenario planning is a powerful new methodology for dealing with these challenges. It enables us to transform ourselves and our relationships and thereby the systems of which we are a part. At a time when divisions within and among societies are producing so many people to get stuck and to suffer, it offers hope-and a proven approach-for moving forward together.

-Vince Cable, Secretary of State for Business, United Kingdom

“All of our toughest problems, from climate change to inequality, have complexity at their heart. Adam Kahane, with his track record of work for social and environmental justice, has written a powerful and practical guide to using scenario planning to transform such problems. This is a book for those hungry for new ideas about how to achieve change.”

-Phil Bloomer, Director, Campaigns and Policy, Oxfam

“We all face challenges and opportunities that can only be addressed with fresh understandings and innovative forms of collaboration. At Shell we have learned the value of combining scenario thinking with strategic choices. Building on his extensive practical experience, Kahane extends the boundaries of this practice.”

-Jeremy Bentham, Vice President, Global Business Environment, Royal Dutch Shell

“This deeply human book offers tangible means for tackling the intractable problems that confront us at every level of life, from domestic and local to national and beyond. It offers realistic, grounded hope of genuine transformation, and its insights and lessons should be part of the toolbox of everyone in leadership roles.”

-Thabo Makgoba, Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town

Preface

Chapter 1: An Invention Born of Necessity: The Mont Fleur Scenario Exercise

Chapter 2: A New Way to Work With the Future

Chapter 3: First step: Convene a Team From Across the Whole System

Chapter 4: Second step: Observe What Is Happening

Chapter 5: Third step: Construct Stories About What Could Happen

Chapter 6: Fourth step: Discover What Can and Must Be Done

Chapter 7: Fifth step: Act to Transform the System

Chapter 8: New Stories Can Generate New Realities: The Destino Colombia Project

Chapter 9: The Inner Game of Social Transformation

Resources: Transformative Scenario Planning Processes

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

About Reos Partners

About the Author

1

An Invention Born of Necessity

ON A LOVELY FRIDAY AFTERNOON in September 1991, I arrived at the Mont Fleur conference center in the mountains of the wine country outside of Cape Town. I was excited to be there and curious about what was going to happen. I didn’t yet realize what a significant weekend it would turn out to be.

THE SCENARIO PLANNING METHODOLOGY MEETS THE SOUTH AFRICAN TRANSFORMATION

The year before, in February 1990, South African president F. W. de Klerk had unexpectedly announced that he would release Nelson Mandela from 27 years in prison, legalize Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) and the other opposition parties, and begin talks on a political transition. Back in 1948, a white minority government had imposed the apartheid system of racial segregation and oppression on the black majority, and the 1970s and 1980s had seen waves of bloody confrontation between the government and its opponents. The apartheid system, labeled by the United Nations a “crime against humanity,” was the object of worldwide condemnation, protests, and sanctions.

Now de Klerk’s announcement had launched an unprecedented and unpredictable process of national transformation. Every month saw breakthroughs and breakdowns: declarations and demands from politicians, community activists, church leaders, and businesspeople; mass demonstrations by popular movements and attempts by the police and military to reassert control; and all manner of negotiating meetings, large and small, formal and informal, open and secret.

South Africans were excited, worried, and confused. Although they knew that things could not remain as they had been, they disagreed vehemently and sometimes violently over what the future should look like. Nobody knew whether or how this transformation could happen peacefully.

Professors Pieter le Roux and Vincent Maphai, from the ANC-aligned University of the Western Cape, thought that it could be useful to bring together a diverse group of emerging national leaders to discuss alternative models for the transformation. They had the idea that the scenario planning methodology that had been pioneered by the multinational oil company Royal Dutch Shell, which involved systematically constructing a set of multiple stories of possible futures, could be an effective way to do this. At the time, I was working in Shell’s scenario planning department at the company’s head office in London. Le Roux asked me to lead the meetings of his group, and I agreed enthusiastically. This is how I came to arrive at Mont Fleur on that lovely Friday afternoon.

My job at Shell was as the head of the team that produced scenarios about possible futures for the global political, economic, social, and environmental context of the company. Shell executives used our scenarios, together with ones about what could happen in energy markets, to understand what was going on in their unpredictable business environment and so to develop more robust corporate strategies and plans. The company had used this adaptive scenario planning methodology since 1972, when a brilliant French planning manager named Pierre Wack constructed a set of stories that included the possibility of an unprecedented interruption in global oil supplies. When such a crisis did in fact occur in 1973, the company’s swift recognition of and response to this industry-transforming event helped it to rise from being the weakest of the “Seven Sisters” of the international oil industry to being one of the strongest. The Shell scenario department continued to develop this methodology, and over the years that followed, it helped the company to anticipate and adapt to the second oil crisis in 1979, the collapse of oil markets in 1986, the fall of the Soviet Union, the rise of Islamic radicalism, and the increasing pressure on companies to take account of environmental and social issues.1

I joined Shell in 1988 because I wanted to learn about this sophisticated approach to working with the future. My job was to try to understand what was going on in the world, and to do this I was to go anywhere and talk to anyone I needed to. I learned the Shell scenario methodology from two masters: Ged Davis, an English mining engineer, and Kees van der Heijden, a Dutch economist who had codified the approach that Wack invented. In 1990, van der Heijden was succeeded by Joseph Jaworski, a Texan lawyer who had founded the American Leadership Forum, a community leadership development program that was operating in six US cities. Jaworski thought that Shell should use its scenarios not only to study and adapt to the future but also to exercise its leadership to help shape the future. This challenged the fundamental premise that our scenarios needed to be neutral and objective, and it led to lots of arguments in our department. I was torn between these two positions.

Wack had retired from Shell in 1980 and started to work as a consultant to Clem Sunter, the head of scenario planning for Anglo American, the largest mining company in South Africa. Sunter’s team produced two scenarios of possible futures for the country as an input to the company’s strategizing: a “High Road” of negotiation leading to a political settlement and a “Low Road” of confrontation leading to a civil war and a wasteland.2 In 1986, Anglo American made these scenarios public, and Sunter presented them to hundreds of audiences around the country, including de Klerk and his cabinet, and Mandela, at that time still in prison. These scenarios played an important role in opening up the thinking of the white population to the need for the country to change.

Then in 1990, de Klerk, influenced in part by Sunter’s work, made his unexpected announcement. In February 1991 (before le Roux contacted me), I went to South Africa for the first time for some Shell meetings. On that trip I heard a joke that crystallized the seemingly insurmountable challenges that South Africans faced, as well as the impossible promise of all their efforts to address these challenges together. “Faced with our country’s overwhelming problems,” the joke went, “we have only two options: a practical option and a miraculous option. The practical option would be for all of us to get down on our knees and pray for a band of angels to come down from heaven and solve our problems for us. The miraculous option would be for us to talk and work together and to find a way forward together.” South Africans needed ways to implement this miraculous option.

THE MONT FLEUR SCENARIO EXERCISE

Necessity is the mother of invention, and so it was the extraordinary needs of South Africa in 1991 that gave birth to the first transformative scenario planning project.3 Le Roux and Maphai’s initial idea was to produce a set of scenarios that would offer an opposition answer to the establishment scenarios that Wack and Sunter had prepared at Anglo American and to a subsequent scenario project that Wack had worked on with Old Mutual, the country’s largest financial services group. The initial name of the Mont Fleur project was “An Alternative Scenario Planning Exercise of the Left.”

When le Roux asked my advice about how to put together a team to construct these scenarios, I suggested that he include some “awkward sods”: people who could prod the team to look at the South African situation from challenging alternative perspectives. What le Roux and his coorganizers at the university did then was not to compose the team the way we did at Shell—of staff from their own organization—but instead to include current and potential leaders from across the whole of the emerging South African social-political-economic system. The organizers’ key inventive insight was that such a diverse and prominent team would be able to understand the whole of the complex South African situation and also would be credible in presenting their conclusions to the whole of the country. So the organizers recruited 22 insightful and influential people: politicians, businesspeople, trade unionists, academics, and community activists; black and white; from the left and right; from the opposition and the establishment. It was an extraordinary group. Some of the participants had sacrificed a lot—in prison or exile or underground—in long-running battles over the future of the country; many of them didn’t know or agree with or trust many of the others; all of them were strong minded and strong willed. I arrived at Mont Fleur looking forward to meeting them but doubtful about whether they would be able to work together or agree on much.

I was astounded by what I found. The team was happy and energized to be together. The Afrikaans word apartheid means “separation,” and most of them had never had the opportunity to be together in such a stimulating and relaxed gathering. They talked together fluidly and creatively, around the big square of tables in the conference room, in small working groups scattered throughout the building, on walks on the mountain, on benches in the flowered garden, and over good meals with local wine. They asked questions of each other and explained themselves and argued and made jokes. They agreed on many things. I was delighted.

The scenario method asks people to talk not about what they predict will happen or what they believe should happen but only about what they think could happen. At Mont Fleur, this subtle shift in orientation opened up dramatically new conversations. The team initially came up with 30 stories of possible futures for South Africa. They enjoyed thinking up stories (some of which they concluded were plausible) that were antithetical to their organizations’ official narratives, and also stories (some of which they concluded were implausible) that were in line with these narratives. Trevor Manuel, the head of the ANC’s Department of Economic Policy, suggested a story of Chilean-type “Growth through Repression,” a play on words of the ANC’s slogan of “Growth through Redistribution.” Mosebyane Malatsi, head of economics of the radical Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC)—one of their slogans was “One Settler [white person], One Bullet”—told a wishful story about the Chinese People’s Liberation Army coming to the rescue of the opposition’s armed forces and helping them to defeat the South African government; but as soon as he told it, he realized that it could not happen, so he sat down, and this scenario was never mentioned again.

Howard Gabriels, an employee of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (the German social democratic foundation that was the primary funder of the project) and a former official of the socialist National Union of Mineworkers, later reflected on the openness of this first round of storytelling:

The first frightening thing was to look into the future without blinkers on. At the time there was a euphoria about the future of the country, yet a lot of those stories were like “Tomorrow morning you will open the newspaper and read that Nelson Mandela was assassinated” and what happens after that. Thinking about the future in that way was extremely frightening. All of a sudden you are no longer in your comfort zone. You are looking into the future and you begin to argue the capitalist case and the free market case and the social democracy case. Suddenly the capitalist starts arguing the communist case. And all those given paradigms begin to fall away.4

Johann Liebenberg was a white Afrikaner executive of the Chamber of Mines. Mining was the country’s most important industry, its operations intertwined with the apartheid system of economic and social control. So in this opposition-dominated team, Liebenberg represented the arch-establishment. He had been Gabriels’s adversary in acrimonious and violent mining industry negotiations and strikes. Gabriels later recalled with amazement:

In 1987, we took 340,000 workers out on strike, 15 workers were killed, and more than 300 workers got terribly injured, and when I say injured, I do not only mean little scratches. He was the enemy, and here I was, sitting with this guy in the room when those bruises are still raw. I think that Mont Fleur allowed him to see the world from my point of view and allowed me to see the world from his.5

In one small group discussion, Liebenberg was recording on a flip chart while Malatsi of the PAC was speaking. Liebenberg was calmly summarizing what Malatsi was saying: “Let me see if I’ve got this right: ‘The illegitimate, racist regime in Pretoria …’” Liebenberg was able to hear and articulate the provocative perspective of his sworn enemy.

One afternoon, Liebenberg went for a walk with Tito Mboweni, Manuel’s deputy at the ANC. Liebenberg later reported warmly:

You went for a long walk after the day’s work with Tito Mboweni on a mountain path and you just talked. Tito was the last sort of person I would have talked to a year before that: very articulate, very bright. We did not meet blacks like that normally; I don’t know where they were all buried. The only other blacks of that caliber that I had met were the trade unionists sitting opposite me in adversarial roles. This was new for me, especially how open-minded they were. These were not people who simply said: “Look, this is how it is going to be when we take over one day.” They were prepared to say: “Hey, how would it be? Let’s discuss it.”6

I had never seen or even heard of such a good-hearted and constructive encounter about such momentous matters among such long-time adversaries. I wouldn’t have thought it was possible, but here I was, seeing it with my own eyes.

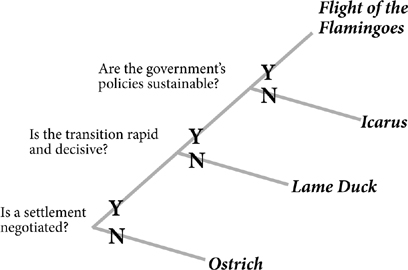

In the following six months, the team and I returned to Mont Fleur for two more weekend workshops. They eventually agreed on four stories about what could happen in the country—stories they thought could stimulate useful debate about what needed to be done. “Ostrich” was a story of the white minority government that stuck its head in the sand and refused to negotiate with its opponents. “Lame Duck” was a story of a negotiated settlement that constrained the new democratic government and left it unable to deal with the country’s challenges. “Icarus” was a story of an unconstrained democratic government that ignored fiscal limits and crashed the economy. “Flight of the Flamingos” was a story of a society that put the building blocks in place to develop gradually and together.7

One of the team members created a simple diagram to show how the scenarios were related to one another. The three forks in the road were three decisions that South African political leaders (who would be influenced by people such as the members of the Mont Fleur team) would have to make over the months ahead. The first three scenarios were prophetic warnings about what could happen in South Africa if the wrong decisions were made. The fourth scenario was a vision of a better future for the country if all three of these errors were avoided. When they started their work together, this politically heterogeneous team had not intended to agree on a shared vision, and now they were surprised to have done so. But both the content of the “Flight of the Flamingos” scenario and the fact that this team had agreed on it served as a hopeful message to a country that was uncertain and divided about its future.

The Mont Fleur Scenarios, South Africa, 1992

The team wrote a 16-page summary of their work that was published as an insert in the country’s most important weekly newspaper. Lindy Wilson, a respected filmmaker, prepared a 30-minute video about this work (she is the one who suggested using bird names), which included drawings by Jonathan Shapiro, the country’s best-known editorial cartoonist. The team then used these materials to present their findings to more than 100 political, business, and nongovernmental organizations around the country.

THE IMPACT OF MONT FLEUR

The Mont Fleur project made a surprisingly significant impact on me. I fell in love with this collaborative and creative approach to working with the future, which I had never imagined was possible; with this exciting and inspiring moment in South African history, which amazed the whole world; and with Dorothy Boesak, the coordinator of the project. By the time the project ended in 1993, I had resigned from Shell to pursue this new way of working, moved from London to Cape Town, and married Dorothy. My future was now intertwined with South Africa’s.

The project also made a surprisingly significant impact on South Africa. In the years after I immigrated to South Africa, I worked on projects with many of the country’s leaders and paid close attention to what was happening there. The contribution of Mont Fleur to what unfolded in South Africa, although not dramatic or decisive, seemed straightforward and important. The team’s experience of their intensive intellectual and social encounter with their diverse teammates shifted their thinking about what was necessary and possible in the country and, relatedly, their empathy for and trust in one another. This consequently shifted the actions they took, and these actions shifted what happened in the country.

Of these four scenarios, the one that had the biggest impact was “Icarus.” The title of the story referred to the Greek mythical figure who was so exhilarated by his ability to fly using feathers stuck together with wax that he flew too close to the sun, which melted the wax and plunged him into the sea. In his book on Mont Fleur and the two prior South African corporate-sponsored scenario exercises, economist Nick Segal summarized the warning of “Icarus” about the dangers of macroeconomic populism as follows:

A popularly elected government goes on a social spending spree accompanied by price and exchange controls and other measures in order to ensure success. For a while this yields positive results, but before long budgetary and balance of payment constraints start biting, and inflation, currency depreciation and other adverse factors emerge. The ensuing crisis eventually results in a return to authoritarianism, with the intended beneficiaries of the programme landing up worse off than before.8

This scenario directly challenged the economic orthodoxy of the ANC, which in the early 1990s was under strong pressure from its constituents to be ready, once in government, to borrow and spend money in order to redress apartheid inequities. When members of the scenario team, supported by Mboweni and Manuel, presented their work to the party’s National Executive Committee, which included both Nelson Mandela (president of the ANC) and Joe Slovo (chairperson of the South African Communist Party), it was Slovo, citing the failure of socialist programs in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, who argued that “Icarus” needed to be taken seriously.

When le Roux and Malatsi presented “Icarus” to the National Executive Committee of the Pan-Africanist Congress—which up to that point had refused to abandon its armed struggle and participate in the upcoming elections—Malatsi was forthright about the danger he saw in his own party’s positions: “This is a scenario of the calamity that will befall South Africa if our opponents, the ANC, come to power. And if they don’t do it, we will push them into it.” With this sharply self-critical statement, he was arguing that his party’s declared economic policy would harm the country and also its own popularity.

One of the committee members then asked Malatsi why the team had not included a scenario of a successful revolution. He replied: “I have tried my best, comrades, but given the realities in the world today, I cannot see how we can tell a convincing story of how a successful revolution could take place within the next ten years. If any of you can tell such a story so that it carries conviction, I will try to have the team incorporate it.” Later, le Roux recalled that none of the members of the committee could do so, “and I think this failure to be able to explain how they could bring about the revolution to which they were committed in a reasonable time period was crucial to the subsequent shifts in their position. It is not only the scenarios one accepts but also those that one rejects that have an impact.”9

This conversation about the scenarios was followed by a full-day strategic debate in the committee. Later the PAC gave up their arms, joined the electoral contest, and changed their economic policy. Malatsi said: “If you look at the policies of the PAC prior to our policy conference in September 1993, there was no room for changes. If you look at our policy after that, we had to revise the land policy; we had to revise quite a number of things. They were directly or indirectly influenced by Mont Fleur.”10

These and many other debates—some arising directly out of Mont Fleur, some not—altered the political consensus in the opposition and in the country. (President de Klerk defended his policies by saying “I am not an ostrich.”11) When the ANC government came to power in 1994, one of the most significant surprises about the policies it implemented was its consistently strict fiscal discipline. Veteran journalist Allister Sparks referred to this fundamental change in ANC economic policy as “The Great U-Turn.”12 In 1999, when Mboweni became the country’s first black Reserve Bank governor (a position he held for ten years), he reassured local and international bankers by saying: “We are not Icarus; there is no need to fear that we will fly too close to the sun.” In 2000, Manuel, by then the country’s first black minister of finance (a position he held for 13 years), said: “It’s not a straight line from Mont Fleur to our current policy. It meanders through, but there’s a fair amount in all that going back to Mont Fleur. I could close my eyes now and give you those scenarios just like this. I’ve internalized them, and if you have internalized something, then you probably carry it for life.”13

The economic discipline of the new government enabled the annual real rate of growth of the South African economy to jump from 1 percent over 1984–1994 to 3 percent over 1994–2004. In 2010, Clem Sunter observed how well South Africa had navigated not only its transition to democracy but also the later global recession: “So take a bow, all you who were involved in the Mont Fleur initiative. You may have changed our history at a critical juncture.”14

The Mont Fleur team’s messages about the country’s future were simple and compelling. Not everyone agreed with these messages: some commentators thought that the team’s analysis was superficial, and many on the left thought that the conclusion about fiscal conservatism was incorrect. Nevertheless, the team succeeded in placing a crucial hypothesis and proposal about post-apartheid economic strategy on the national agenda. This proposal won the day, in part because it seemed to make sense in the context of the prevailing global economic consensus and in part because Manuel and Mboweni exercised so much influence on the economic decision making of the new government for so long. So the team’s work made a difference to what happened in the country.

Mont Fleur not only contributed to but also exemplified the process through which South Africans brought about their national transformation. The essence of the Mont Fleur process—a group of leaders from across a system talking through what was happening, could happen, and needed to happen in their system, and then acting on what they learned—was employed in the hundreds of negotiating forums (most of them not using the scenario methodology as such) on every transitional issue from educational reform to urban planning to the new constitution. This was the way of working that produced the joke I had heard about the practical option and the miraculous option. South Africans succeeded in finding a way forward together. They succeeded in implementing “the miraculous option.”

Neither the Mont Fleur project in particular nor the South African transition in general was perfect or complete. Many issues and actors were left out, many ideas and actions were bitterly contested, and many new dynamics and difficulties arose later on. Transforming a complex social system like South Africa is never easy or foolproof or permanent. But Mont Fleur contributed to creating peaceful forward movement in a society that was violently stuck. Rob Davies, a member of the team and later minister of trade and industry, said: “The Mont Fleur process outlined the way forward of those for us who were committed to finding a way forward.”15