Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

The handbook of an extraodinary project:

In 1948 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a deeply inspiring document that has been translated into over 300 languages and dialects. But because its provisions are not enforceable, its promise has not been fulfilled. Human rights violations continue in every corner of the globe, the cause of countless individual tragedies as well as large-scale disasters like war, poverty and environmental ruin.

It’s time to take the next step. 2048 sets out a visionary, audacious, but, Kirk Boyd insists, achievable goal: drafting an enforceable international agreement that will allow the people of the world to create a social order based upon human rights and the rule of law. Boyd and the 2048 Project aim to have this agreement, the International Convention on Human Rights, in place by the 100th anniversary of the Universal Declaration.

Written documents have always played a key role in advancing human rights: the Code of Hammurabi, the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence. The express purpose of the International Convention is to safeguard what Boyd calls the Five Freedoms, adding freedom for the environment to Franklin Roosevelt’s famous Four Freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

Boyd skillfully anticipates objections to the notion of a universal and enforceable written agreement—that it would be culturally insensitive, too expensive, unacceptably limit national sovereignty—and convincingly answers them. In fact some promising first steps have already been taken. He describes existing transnational agreements with effective compliance mechanisms that can serve as models.

But Boyd wants to inspire more than argue. In 2048 he urges everyone to participate in the drafting of the agreement via the 2048 website and describes specific actions people can take to help make it a reality. “What you do with what you read” Boyd writes, “is as important as what this book says.” Little by little, working together creatively with the tools now available, we can take the next step forward in the evolution of human rights.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact Leslie Davis ( [email protected] )

The handbook of an extraodinary project:

In 1948 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a deeply inspiring document that has been translated into over 300 languages and dialects. But because its provisions are not enforceable, its promise has not been fulfilled. Human rights violations continue in every corner of the globe, the cause of countless individual tragedies as well as large-scale disasters like war, poverty and environmental ruin.

It’s time to take the next step. 2048 sets out a visionary, audacious, but, Kirk Boyd insists, achievable goal: drafting an enforceable international agreement that will allow the people of the world to create a social order based upon human rights and the rule of law. Boyd and the 2048 Project aim to have this agreement, the International Convention on Human Rights, in place by the 100th anniversary of the Universal Declaration.

Written documents have always played a key role in advancing human rights: the Code of Hammurabi, the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence. The express purpose of the International Convention is to safeguard what Boyd calls the Five Freedoms, adding freedom for the environment to Franklin Roosevelt’s famous Four Freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

Boyd skillfully anticipates objections to the notion of a universal and enforceable written agreement—that it would be culturally insensitive, too expensive, unacceptably limit national sovereignty—and convincingly answers them. In fact some promising first steps have already been taken. He describes existing transnational agreements with effective compliance mechanisms that can serve as models.

But Boyd wants to inspire more than argue. In 2048 he urges everyone to participate in the drafting of the agreement via the 2048 website and describes specific actions people can take to help make it a reality. “What you do with what you read” Boyd writes, “is as important as what this book says.” Little by little, working together creatively with the tools now available, we can take the next step forward in the evolution of human rights.

J. Kirk Boyd is a lawyer, a professor, and the executive dDirector of the 2048 Project. He teaches international human rights, civil rights, free speech, and constitutional law at the University of California, Berkeley.

"It's time for a serious dialogue about an international framework for human rights and business. 0 furthers that dialogue," —Robert Haas, Chairman Emeritus, Levi Strauss & Co. "All great human achievement seems impossible until it happens; and then it was inevitable. 2048 offers us the gift of advanced hindsight. The book provides one vision for how future generations may look back and see just how we met the great challenge of securing human rights in all nations.” —The Honorable Jeffrey L. Bleich, former Special Counsel to the President of the United States

“Kirk Boyd's vision of a global, binding human rights compact underpinned by a system of courts of law, or an International Court of Human Rights, is not just one of the many possible future scenarios. It is essential if international law is to make the quantum leap from a mere system of laws to a true legal order.” —Cesare Romano, Professor, Loyola Law School and Assistant Director, Project on International Courts and Tribunals

“There is nothing more fundamental than for humanity to reach an agreement to live together. The European Convention on Human Rights already works for forty-seven countries. Kirk Boyd points the way to a universal approach along similar lines.” —Jurriaan Kamp, publisher, Ode

“It's time for economic and social rights such as education and health care for women and men in all countries -- 2048 shows how we might achieve this goal.” —Joan Blades, cofounder, MoveOn.org and MomsRising.org

“ 2048 has a grand participatory vision, which will change not only the way we view the world but the way we interact with it and with each other. It is a project that must succeed if we are to have a more decent human future.” —David Krieger, President, Nuclear Age Peace Foundation

“People working for social change should read 2048 . It gives a new perspective on how some of the resources currently channeled toward solving the problems arising from our flawed existing social order might be better repurposed toward restructuring the system that is creating these problems. 2048 shows the way.” —Caroline Avery, President, Durfee Foundation

“Human rights are a permanent vocation. Even after the wonderful work of codification by the United Nations and of the regional human rights commissions and courts, reflection goes on, because we need better mechanisms of implementation, such as the World Court of Human Rights envisaged by Project 2048. This is a noble task that should reflect the views of all of humanity, including the approaches of the thinkers and lawyers of Central and South America."

—Jose Ayala Lasso, first United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

“It's heartening to see a global dialogue developing through 2048 that can lead humanity to an agreement to live together. With this inspiring, visionary book, Kirk Boyd not only raises awareness of the unfolding 2048 story, he provides a catalyst for people all over the world to join in the conversation themselves.” —John Esterle, Executive Director, Whitman Institute

“Many great, but unenforceable, legal opinions have been written by the committees within the United Nations. It's time for a project such as 2048 that will build enforceable decisions upon this foundation.” —Alfred de Zayas, legal counsel for the United Nations Human Rights Committee

“Harry Truman wanted there to be an International Bill of Rights, and I'm glad to see one coming into existence through the 2048 Project.” —Frank Kelly, author and speechwriter for President Truman

"I'm glad to be working through 2048 to equip barristers in all countries with an International Bill of Rights they can use to enforce rights in their courts of law." —James J. Brosnahan, Trial Lawyer, Morrison & Foerster

"Boyd proposes an ambitious new social contract for humanity which could serve as a tipping point for enforcing human rights worldwide" --Jill Van den Brule, Communications Specialist, Education and Gender Equality, UNICEF and international child rights advocate

Timeline for the achievement of The 2048 Project

Introduction: Breaking Our Chains

Part One: How the 2048 Movement Began

Chapter 1: Turning Point for Humanity

Chapter 2: Challenges and Opportunities

Part Two: What the 2048 Movement Is

Chapter 3: Five Freedoms for All

Chapter 4: Freedom of Speech

Chapter 5: Freedom of Religion

Chapter 6: Freedom from Want

Chapter 7: Freedom for the Environment

Chapter 8: Freedom from Fear

Part Three: Where the 2048 Movement is Headed

Chapter 9: Regional Agreements to Live Together

Chapter 10: Humanity's Agreement to Live Together

Chapter 11: The Path Together

Chapter 12: Focus Together

Chapter 13: Think Together

Chapter 14: Write Together

Chapter 15: Decide Together

Conclusion: Forward Together

Resources

A: Universal Declaration of Human Rights

B: Draft International Convention on Human Rights

Notes

Photo Credits

Acknowledgments

Index

2048 Follow-up

About the Author

CHAPTER 1

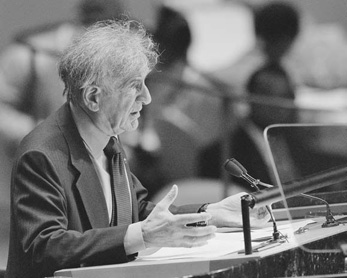

Elie Wiesel speaks for the conscience of humanity

Turning Point for Humanity

In Night, Elie Wiesel wrote this eyewitness account of what he saw as a prisoner at a Nazi concentration camp:

Not far from us, flames, huge flames, were rising from a ditch. Something was being burned there. A truck drew close and unloaded its hold: small children. Babies! Yes, I did see this with my own eyes . . . children thrown into the flames. (Is it any wonder that ever since then, sleep tends to elude me?) 12

This moment, as the stench of burning human flesh rushed up into his nostrils, was a turning point for humanity. The turn is not yet completed, but here it began. Why was this moment a turning point? Hadn’t this type of thing happened before? Yes, of course it had. But it was a turning point because after the despicable acts of the 1930s and 1940s, humanity collectively bound together in 1948 and said, “never again.” Humanity decided to create a new system of rules for those who govern, a new agreement that would not allow such acts to happen again. “Never again” was the goal, not only for Jewish people, but for all of humanity. 13

With the 1948 beginning of a 100-year turn etched in our minds, let’s now consider what it will be like at the end of that turn in the year 2048. At the end of the turn, there will be humanity’s written agreement to live together embodied in an International Bill of Rights that is enforceable in the courts of all countries. Now that we have a clear beginning and end, the rest of this book will fill in all that has happened since the beginning and all that needs to happen to reach the end.

I have a specific example of how writing our agreement to live together into an enforceable document will work. I began my career after law school at a large law firm, Morrison & Forester, in San Francisco, California. I was trained as a trial lawyer. My mentor is a legendary barrister, James Brosnahan. Jim is the kind of lawyer you can go to no matter what kind of trouble you are having, whether it’s with a person, a business, or a government. If someone has done you wrong, no matter how powerful he or she may be, Jim will go to court, talk to a judge or a jury, and make it right.

How does he do this? In the breast pocket of his shirt Jim always carries a copy of the U.S. Constitution. For over fifty years he has used it in courtrooms across the land, including the U.S. Supreme Court, to protect the rights of all people — from a poor Mexican woman who was part of the Sanctuary movement, to a chief executive officer of a major corporation. 14

Having learned from Jim, I also have my own bound copy of the U.S. Constitution, and I have used it in many courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. The Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution is both a sword and a shield. It empowers people to stand before a judge to obtain an order against government officials to make them do something, or to stop doing something. With the Bill of Rights, Americans — regardless of their race, sex, age, religion, and creed — can enforce their agreement to live together, as well as their agreement with their government.

I have handled many free speech cases. The free speech guarantee in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution enables lawyers like me and any other lawyer in America to stop the government when it tries to interfere with people or organizations engaged in free speech. The Bill of Rights also guarantees other freedoms, including the freedom of religion. Our agreement to live together is fully realized because our rights can be enforced in court.

This process, the ability to stand before a judge with a document and obtain an order to protect rights, is at the very heart of the 2048 plan. Human rights are never fully realized unless you can stand before a judge and enforce them. In fact, this process works so well that it has given rise to a movement to make the protection of rights by judges regional and international. Today, lawyers in forty-seven countries in Europe are carrying copies of the European Convention on Human Rights, in their pockets and briefcases, and they are obtaining orders based on that document.

2048 follows this European example, by drafting an International Bill of Rights that applies in all regions of the world. Human rights are universal; therefore they must be enforceable in the courts of all countries. No one should be free from slavery in one country but not another; no one should have the right to education in one country but not another, and no one should have the right to speak out against the government in one country but not another. The question, therefore, is the following: What will be the wording of the document that will eventually be in the pockets of lawyers in all countries? The 2048 Project provides a way for our international community to decide what the wording of the document will be. The enforceable document produced through the 2048 process is the end of the 100-year turn.

Although it will take some time for this International Bill of Rights to be taken out of pockets and briefcases and used in courtrooms all over the world, through 2048 we are preparing for that day. You can see a draft of this International Bill of Rights today by looking at Resource B in the back of this book, and by going to the 2048 website. The existing draft is only a starting point, not a finished document.

It may seem premature to build a document that may not be used for many years, but I think we have a valuable lesson to learn from the South Korean people. While at a meeting of the World Federation of United Nations Associations in Seoul, Korea, I went to visit the Demilitarized Zone. To my amazement I saw a beautiful train station right on the border with North Korea — the Dorasan Station. It is a large and immaculate structure with sweeping contemporary architecture. But no trains arrive and depart from there. South Koreans have built that station based on their determination that one day South and North Korea will be reunited and the trains will come. So it is with the 2048 Project. We will build an International Bill of Human Rights now and it will be used later. Someday trains will be regularly pulling into Dorasan Station, and an International Bill of Rights will be regularly pulled out in courtrooms in all countries. Both will be happy occasions.

Equally important, the International Bill of Rights that is being written through the 2048 process will not only be pulled out of the breast pockets and briefcases of lawyers, it will also be pulled out of the backpacks and book bags of students in classrooms in all schools in all countries! Joanna Kim works with the 2048 Project. When Joanna was in high school she was a member of a constitution team that debated about the content and application of the U.S. Constitution, including the Bill of Rights. Joanna had a bound version of the U.S. Constitution that she would pull from her backpack and use to argue before teachers, just as Jim Brosnahan pulls the constitution from his breast pocket to argue in court.

When the constitution is pulled out of Jim’s pocket or Joanna’s backpack it is used as the basis for upholding Americans’ agreement to live together. It says, “Here’s the deal,” and when people from the classroom to the courtroom learn of this agreement, and pull out the Bill of Rights to use it, then it becomes the very fabric of the culture, and it is respected, not only because judges enforce it, but also because those rights become part of everyday life. To this end, the ultimate outcome of 2048 is respect for one another through an understanding about the rights we all share.

So here are the three steps for the entire 100-year turn: First, we write our agreement to live together. Second, we insist that those in power make our agreement enforceable law in exchange for our allowing them to govern. Third, we teach students about our agreement and we go to court to enforce our agreement, because history has shown that even a written agreement may be violated by government officials unless we go to court and obtain orders to stop them. The struggle to maintain rights is ongoing and equal to the struggle to create them.

Looking Back in Order to Go Forward

Now that we have both the beginning and end of the turning point for humanity clearly in mind, let’s go back to the beginning in greater detail to give us clarity about how to go forward. As we look back at the horrors of World War II, the starting point was the goal of preventing such atrocities in the future. To fulfill this goal, a list of rights was created. For thousands of years — with sticks, stones, bullets, and bombs — our ancestors have dominated one another through force. At the same time there has been a steady progression of documents that have not been completely effective, but they do represent a gradual evolution toward an alternative to brute force.

This writing process began with Hammurabi’s code in Babylon, 1795 BCE, and was continued through the Charter of Cyrus, Persia, 539 BCE, English Magna Carta, 1215, the American Declaration of Independence, 1776, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, 1789, and the U.S. Bill of Rights, 1791. After more than fifty million soldiers and civilians were killed in World War II, we collectively said, enough, we will not allow the person with the biggest club or the most powerful gun to ruin and take our lives. We then turned our attention to a new list of rights that embodied four fundamental rights for all people in all countries.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a short list he called the Four Freedoms in his State of the Union address in 1941: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. 15 The 2048 movement, and all of the forthcoming chapters in this book, are about the genuine realization of these Four Freedoms, along with a new Fifth Freedom that is imperative with our times, Freedom for the Environment.

At the end of the war these Four Freedoms were built into the Charter of the United Nations. 16 Support for the protection of these fundamental rights came from a wide cross-section of international civil society, including nongovernment and government organizations from many countries. Through a cooperative effort among nonprofit groups and government representatives, our international community seized on its ability to put a new agreement into writing so that it could be enforced against those who govern. 17

This new framework for universal human rights came to life in San Francisco in 1945 as the world joined together to draft the U.N. Charter. Delegates from countries around the globe passed between four giant columns as they streamed into the War Memorial Opera Building for meetings. The four columns represented the foundation of humanity’s new agreement to live together. Each column represented one fundamental freedom to which all people, in all countries, are entitled. President Roosevelt had made it perfectly clear in his speech that these Four Freedoms had to apply “everywhere in the world.” The President was so emphatic about the international application that he hand wrote in the words “everywhere in the world” after each freedom. Roosevelt understood that for humanity to make the turn from war to peace we have to turn together.

Unfortunately, President Roosevelt died before the U.N. Charter was completed. However, his list of four fundamental rights lived on. The delegates to the United Nations built in the creation of a new Commission on Human Rights as a core part of the United Nations, and the new U.S. president, Harry Truman, stated at the closing ceremony of the United Nations in San Francisco that “the first task of the new Commission is to draft an International Bill of Rights.” 18 The expectation was that a new International Bill of Rights would embody the Four Freedoms for all people. A new agreement was to emerge from the ashes of war! Something was to be gained from all that had been lost.

A new draft of the International Bill of Rights emerged under the leadership of a diverse group of people on the Commission on Human Rights. Eleanor Roosevelt, following in her husband’s footsteps and striding on her own, became the chair of the Commission. She worked with René Cassin from France, P. C. Chang from China, Charles Malik from Lebanon, John Humphrey from Canada, and many others, to draft a new document.

While it was understood at the beginning that they were to write an International Bill of Rights, it became apparent that they did not have the political support for a document that could be enforced in courts against governments. The Cold War was a major reason there was a lack of political support for an enforceable International Bill of Rights. As a by-product of the Cold War, the West and the East became polarized with respect to civil and political rights and economic and social rights. Despite the inclusion of both civil and political (e.g., free speech and freedom of religion), and economic and social (e.g., education and health care) rights within the Universal Declaration, fragmentation developed in which civil and political rights were called “first generation,” while economic and social rights were supposedly “second generation.” This false hierarchy did not reflect the equal status of all rights as intended in the Declaration. One of the main purposes of the 2048 movement is to repair this fragmentation and boost economic and social rights up to the equal status they originally had and which they deserve.

Another reason for the opposition to an enforceable International Bill of Rights was that in 1948 segregation was still part of the law of the United States, and the British empire was still practicing colonialism. While acknowledging the important role that both the United States and Great Britain had in the formation of the Universal Declaration and the emergence of human rights after World War II, it is also necessary to accept that there were strong forces of dominance and prejudice in those countries. U.S. Senators from the South, for example, did not want an enforceable International Bill of Rights that would make them eliminate segregation because they resisted the notion that equality was a fundamental right. This historical blemish is another reason that we should be working for enforceable human rights. 19

Given the strong opposition to an enforceable Bill of Rights, Eleanor and others, not wanting the entire agreement to fail, took the wise step of drafting an unenforceable “declaration” of rights instead of an enforceable International Bill of Rights. It was their belief that a Declaration would still serve the important purpose of putting an agreement into writing. Once in writing, even if it was legally unenforceable, it would have a strong moral force and future documents could be written that would make the rights in a Declaration enforceable in courts of law. 20 The result was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which was adopted unanimously by all countries on December 10, 1948. This was a brilliant continuation of the turn for humanity. In the aftermath of the slaughter of World War II, a written document emerged with a long list of specific rights for people everywhere in the world.

The Four Freedoms were built into the Universal Declaration by including them in the Preamble:

The advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people.

Starting with the Four Freedoms as the “highest aspiration” of the common people was an emphatic statement that the common people were building a new social order that would govern their lives. By putting their rights into a document, the people made it clear to political representatives in government that in exchange for being given the power to govern they must abide by a list of rights to assure a decent life for all people regardless of nationality, profession, caste, sex, and other personal differences.

The framers of the Universal Declaration understood that putting our social contract into writing does not make it immediately enforceable, and they were not so naïve as to think that this would happen. After thousands of years of brutes beating down and shooting people, it was not expected that the brutality would stop overnight with the writing down of rights on paper, and it didn’t. The important thing, however, is that even though it was understood to be a long, ongoing process, immediately after World War II, using our ability to read and write (which sets us apart from all other species), people set out to devise a social order — whether it is among nations, or between a man and a woman — in which the club did not prevail. Despite expectations that some individuals and nations would continue to act like brutes, because some always will, the Universal Declaration provided a written framework of human rights for all people in all countries to curb these tendencies. They knew it would take time, but they were confident that the movement would continue and 2048 shows they were right. As Eleanor Roosevelt said at the time, “The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.”

Given the inability to create an enforceable document because of the influence of the Cold War, the drafters also built language into the end of the Universal Declaration, Article 28, which prepared the path for future documents to make the rights in the Universal Declaration enforceable in courts of law. Article 28 states, “Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.”

Following this vision of future documents to make the Universal Declaration enforceable, two “twin” covenants, the Covenant on Economic and Social Rights and the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, were ratified in 1976. These treaties have been signed by many countries and have contributed to the enforceability of the Universal Declaration. These Covenants, however, are riddled with exceptions and the “reports” by countries about the progress they are making are typically whitewashed. In almost all countries these Covenants are not enforceable in courts. The Civil and Political Covenant does have a committee that issues opinions when countries agree to accept these opinions, but the opinions are nonenforceable.

The lack of legal or economic repercussions against states for violations of human rights translates to widespread impunity for human rights violations. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are wonderful organizations, but “blame and shame” of governments is no longer enough. These organizations have awakened our human conscience, but now it is time to use that awakening to create legal ramifications for the violation of human rights.

It is not a complete surprise that these Covenants are weak and we are stuck halfway through the turn with reports and unenforceable opinions. One of the foremost authorities on international law, H. Lauterpacht, expressed concern at the time of the passage of the Universal Declaration. He wrote that it was dangerous to pass an unenforceable statement of rights because it would give the impression that it was law, when it was not. In his seminal book, International Law and Human Rights, he expressed his reservations by foretelling the problem we now face:

. . . there is nothing in the Declaration adopted by the General Assembly which includes — or implies — any legal limitation upon the freedom of states. It leaves that freedom unimpaired. In that vital respect it marks no advance in the enduring struggle of man against the omnipotence of the State. The moral authority of a pro nouncement of this kind cannot be created by affirmations claiming for it such authority. 21

Despite Lauterpacht’s forewarnings, many people today continue to talk about the Universal Declaration as if it is enforceable. We should not continue to recite the Universal Declaration like a mantra with the mistaken impression that somehow enough incantations will make it enforceable in courts. Even worse, constantly teaching children that they have these “rights” when they are unenforceable provokes skepticism among our youth. I once worked with several nonprofit organizations sponsoring a play at a large public high school in San Francisco. The play was performed on “International Human Rights Day,” December 10, as part of a celebration of the day that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted.

With the guidance of professional directing, the students were allowed to write their own play. To my surprise, the play began with students at center stage tearing in half booklets of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and throwing them down on the stage! Why? Because of the disconnect they felt between the rights listed in the Universal Declaration and the experience of those rights in their daily lives.

They chanted while tearing:

A right to health care? Then why don’t I have any?”

Equality? Then why aren’t women paid the same?”

Education? Where’s my place at the university?”

And who can blame them? The rights in the Universal Declaration have been read to audiences repeatedly (I have heard it many times), but they have yet to be realized.

In addition, hundreds of websites recite the rights in the Universal Declaration until human rights start to sound like fantasy, not reality. Fortunately, as the play progressed, the chanters gradually reclaimed these rights by demanding, and then portraying, the realization of them. What struck me at the time was that these young people viewed rights as something they should live, not just learn about. These students are a good example for us to follow. Humanity is stuck part way through the turn, and they inspire us to keep on going until the rights in the Universal Declaration are genuinely realized by all people.

2048 helps remedy the greatest deficiency of the Universal Declaration: its lack of enforceability. As Lauterpacht further stated: “There are no rights unless they are accompanied by remedies.” 22 The International Bill of Rights that is being drafted as part of 2048 takes the Universal Declaration, along with important covenants, and combines them into a single document that is enforceable in all courts. This International Bill of Rights creates an International Court of Human Rights to enforce the document so there is always genuine accountability.

In addition to enforcement of the Universal Declaration, there is another important reason for us to prepare an International Bill of Rights today: the process of writing and implementing an International Bill of Rights will ensure genuine consent by all countries. There were only 53 countries in the world when the Universal Declaration was adopted unanimously, today there are 192. These additional 139 countries should be given the opportunity to participate in an international dialogue about the human rights to be included in a new document, rather than just being told that they should go along with the Universal Declaration and that it applies to them as a matter of customary law.

Some supporters of human rights fear opening up such a direct dialogue, but when it comes to a social contract, as with any agreement, it’s better to be up front about what is being agreed to. The recent adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Rights for the European Union shows that when the process is opened up even more rights can be created. The new European Rights Charter includes education and health care as enforceable rights in 27 countries! 23 Besides, consent is essential to later enforcement because there will be genuine acceptance rather than the imposition of human rights standards.

It’s also valuable to have all countries directly involved because it is within those countries where human rights will come to be fully realized. It’s important to understand that the 100-year turn does not end at the United Nations — it ends at local courthouses. The International Court of Human Rights created by 2048 is not part of the U.N. system, it is outside of the United Nations. The same is true for the European Court of Human Rights; it too is outside of the United Nations.

The first place for the enforcement of the International Bill of Rights drafted by 2048 is the local courthouses. By the year 2048, human rights should be enforceable in the local courthouses of all countries. This is the goal. Whenever human rights are being violated the first stop should be the local courthouse. Where necessary, the international community should invest in improving inadequate facilities and compensating underpaid judges.

This is the approach that is used for the European Convention on Human Rights; it first applies in the local courts of all 47 European countries before the cases ever go up to the European Court of Human Rights. The application of the International Bill of Rights in the 2048 plan is what separates it from so many other aspirational statements. The 2048 International Bill of Rights is more than another statement of hope for rights, or a declaration of rosy intentions. It does more than require countries to fill out some reports in which they halfheartedly claim they are making progress toward realizing rights. Humanity has enough of those. Such statements are an insufficient social contract and no longer reflect the extent of our ability to read, write, and communicate with one another to create a just contract among ourselves and with those who govern. Today we can do better. 24

Just because an International Bill of Rights and the court that enforces it are designed to be outside of the United Nations does not mean that the United Nations does not have an important role to help complete the turn. To the contrary, as we have seen through our discussion of the U.N. Charter and the Commission on Human Rights that drafted the Universal Declaration, there is important work for the United Nations to do. The Human Rights Council, the successor to the Commission on Human Rights that drafted the Universal Declaration, should join in this work. The primary reason we now have an international social movement to complete the turn by the year 2048 is that thousands of organizations and individuals have dedicated their lives, and their funds, to steadily building up human rights so they now have become part of the thinking and expectations of people throughout the world. Much of this has been done through the United Nations.

However, while the Human Rights Council should be involved, we must also be realistic and accept as fact that the Council cannot be counted on to act on its own to make the rights in the Universal Declaration legally enforceable. Many representatives of the national delegations at the Council have forgotten their power is derived from the people they represent, or they have little flexibility because they are tightly controlled by their governments. Too often the rest of us have accepted the role of begging for changes to be made to our social order rather than exercising our power to restructure and rebuild that order. The only way that we will complete the turn and the rights in the Universal Declaration will become legally enforceable in all countries is by creating an international social movement that demands it, not by patiently asking governments to act. This highlights a major difference between 2048 and most human rights efforts — while governmental representatives are welcome, 2048 is not asking them for permission. 2048 is an international movement outside of government; it is the people of all countries thinking and writing together to reach their own agreement that governments must implement. This is what has happened with the Charter of Fundamental Rights for the European Union, and it will happen for the rest of the world as well.

From time to time we must lead our leaders, or accept the domination of special interests who lead them when we shirk our responsibility. It’s not sacrilegious to acknowledge the deficiencies in the Universal Declaration and to act together to correct them. Even Eleanor Roosevelt noted in her journal on the night of the passage of the Universal Declaration, December 10, 1948 — a date that I celebrate with others every year — that she wondered how valuable it would be to have a declaration that was unenforceable. 25

The answer to Eleanor’s contemplation is that the Declaration has been invaluable. Without the Universal Declaration we would not be partly through the turn. Thanks to this start we can now convert the Declaration into law. As former U.S. Vice President Al Gore recently said, “It’s important to change light bulbs, but it’s more important to change the law.” 26 Whether it is enforceable law to prevent climate change, or enforceable law to ensure the equality of women, the law is not going to change sufficiently unless it rewritten by the people, not governments. Al Gore is not the first leader to stress that it is up to the people to act to change the law. Thomas Jefferson said, “Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone . . . the people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories.” 27

This quid pro quo, an exchange of one thing for another — in this case a list of rights in exchange for the power to govern — is not difficult to understand. If you think about our daily lives; we do it all the time. In business we make agreements, “I’ll let you use the land, but there are limits on how you may use it.” Or with our children, “OK, you can go out, but there are limits on what you can do and you had better follow them.” It is the same for government. We, the citizens of all countries, allow those we elect to govern, but there are limits on what they can do and obligations they must fulfill. Such is our undertaking with the 2048 social movement.

It takes a lot of energy to build a house on a foundation, and it will take a lot of energy to build a new, enforceable document on the Universal Declaration and other documents. But we are great builders! We can do anything we set our collective minds to do. This is what the twenty-first century offers us. The challenge is not whether we can complete the turn, it’s whether we show up to do the job. Fortunately, responsibility gravitates to those who accept it, and people around the world are accepting responsibility by putting their hands and minds together through the 2048 process to draft humanity’s agreement to live together. Let us now look at the challenges and opportunities before us to write our agreement to live together and finish this 100-year turning point for humanity.